The headlines from last week sounded dire. It began when China’s May economic activity report was disappointing, with industrial production, retail sales, and fixed-asset investment missing market expectations.

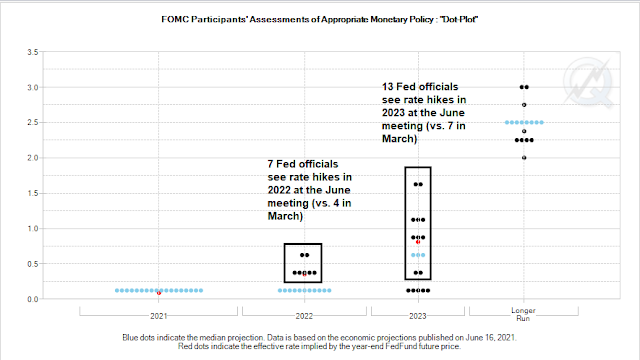

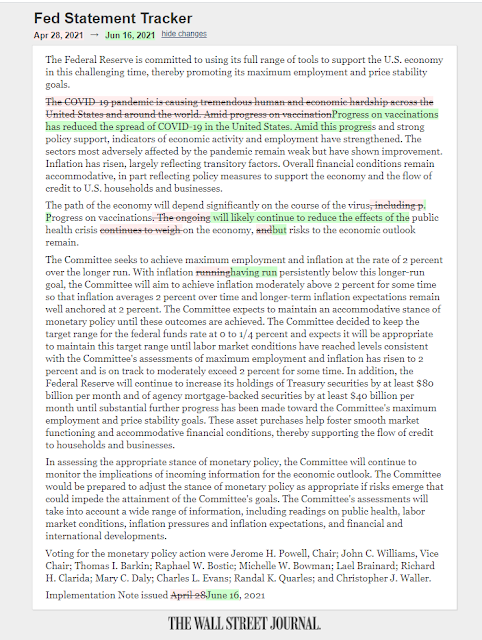

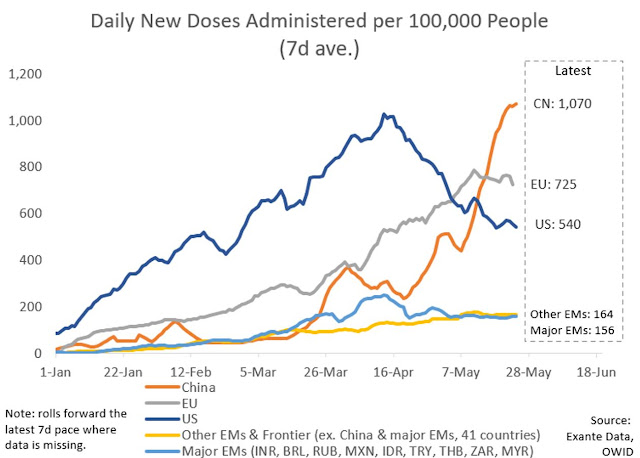

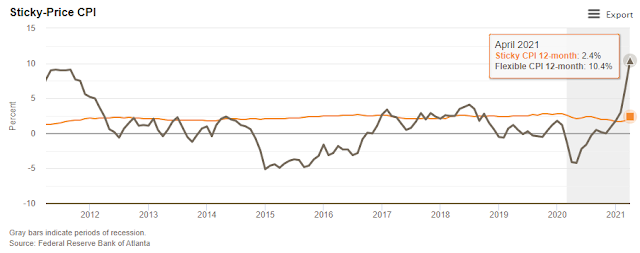

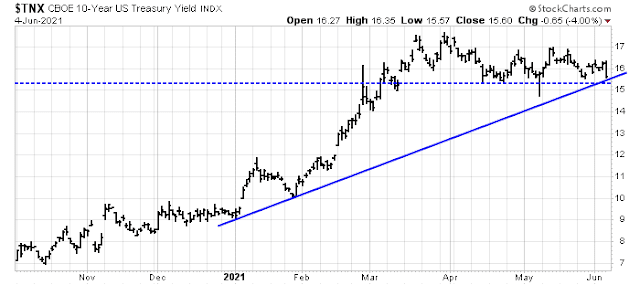

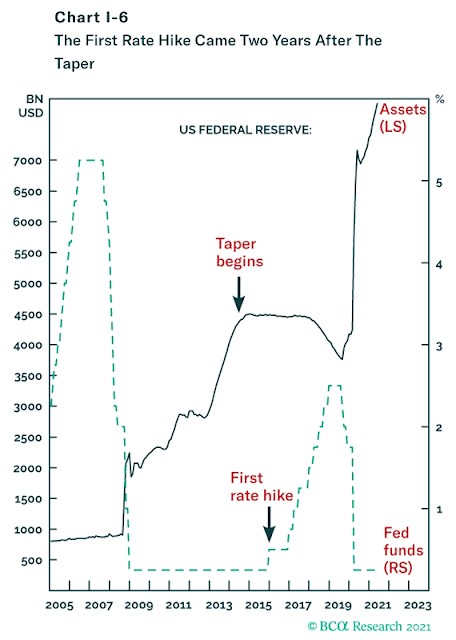

Then the Federal Reserve took an unexpected hawkish turn. The statement from the FOMC meeting acknowledged that downside risks from the pandemic were receding as vaccination rates rose. It raised the 2021 inflation forecast dramatically, shaded down next year’s unemployment rate, and projected two rate hikes in 2023 compared to the previous forecast of no rate hikes. As well, a taper of its quantitative easing program is on the horizon.

Collapsing global trade and growth. Rising interest rates. It sounds like the start of a major risk-off episode.

My own reading of cross-asset market signals comes to a different conclusion. China’s slowdown is stabilizing, which may serve to put a floor on global risk appetite and equity prices.

Mapping China’s slowdown

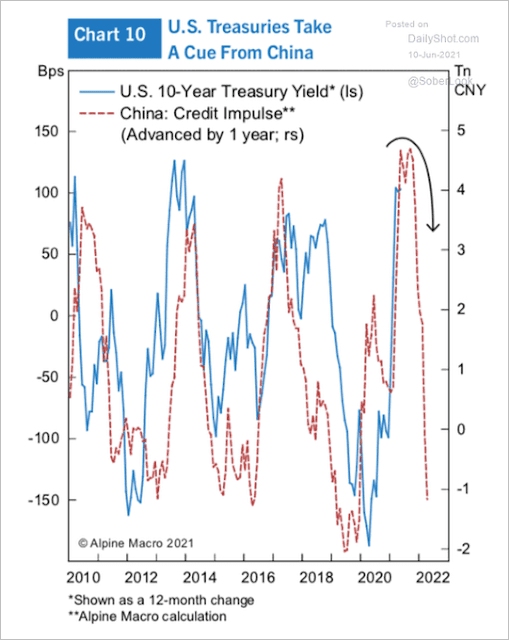

In the past few months, there has been growing concern over a slowdown in China’s credit growth. Total social financing (TSF) has been rolling over as Beijing normalized policy after the pandemic.

These conditions have sounded the alarm over a China slowdown. Historically, this has led to negative consequences for global growth and capital market returns.

China watcher Michael Pettis gave a more optimistic interpretation in a

Twitter thread.

TSF will grow 9.3% in 2021. This is roughly equal to consensus nominal GDP growth expectations, in which case we will have seen a stabilization of China’s debt-to-GDP ratio – something Beijing has promised will happen this year. Because we’re all expecting last year’s contraction in consumption to be partially reversed this year – and not just in China – 2021 will be the only year in which Beijing has a real shot at stabilizing Chinese leverage even as GDP continues to grow quickly.

Shehzad Qazi of China Beige Book, which monitors the Chinese economy from a bottom-up perspective, noted that “among firms that borrowed new lending (rather than rollovers/credit extensions) did rise”, indicating that credit is going to more productive activities than just rollovers.

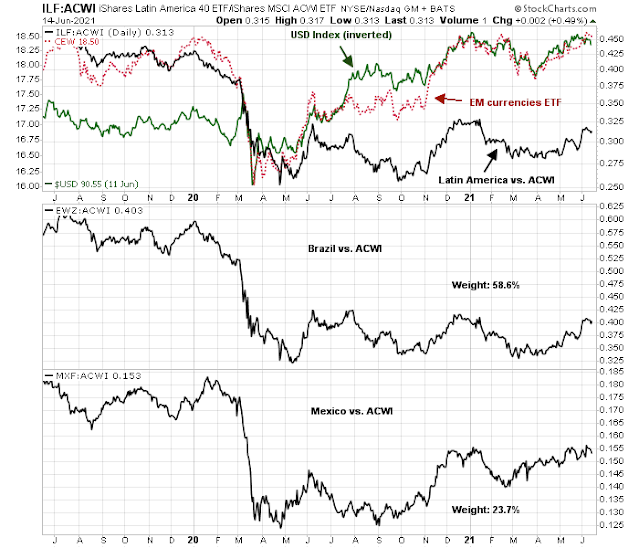

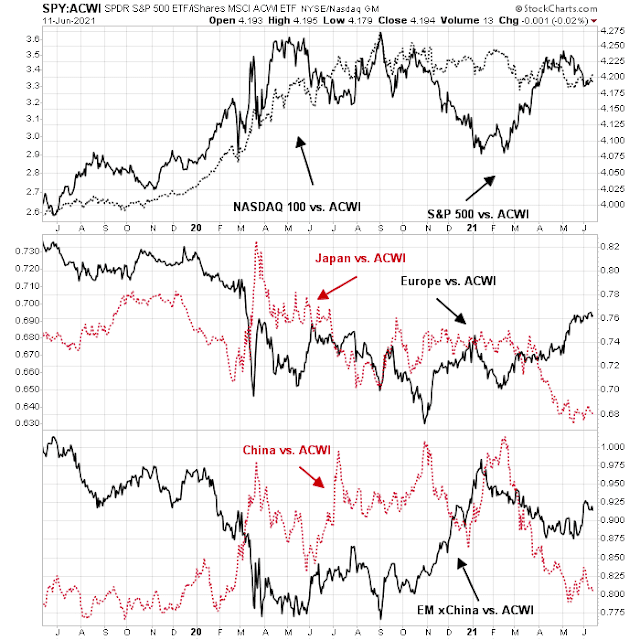

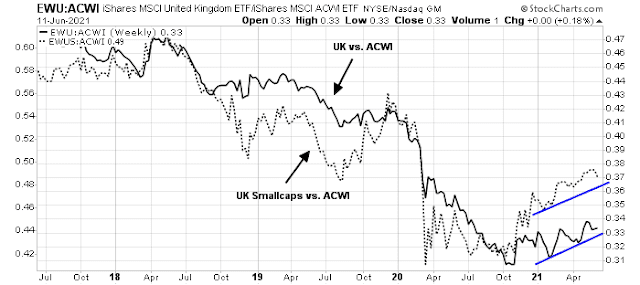

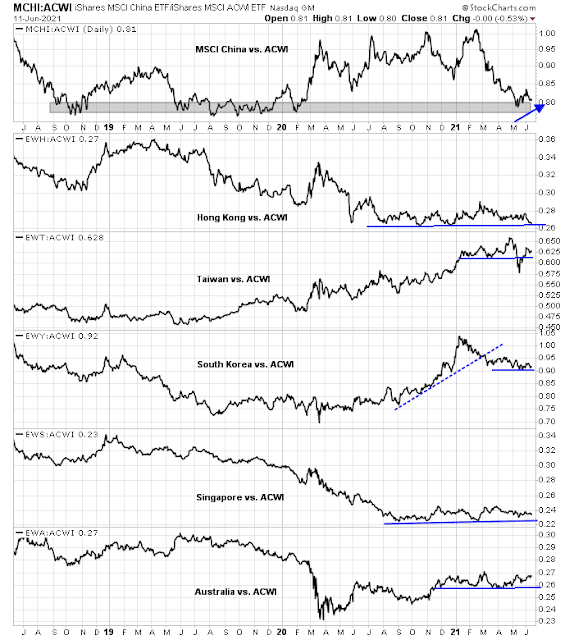

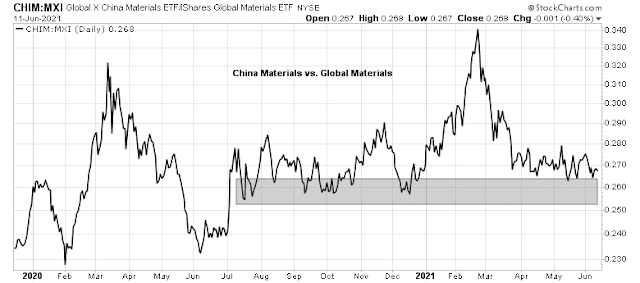

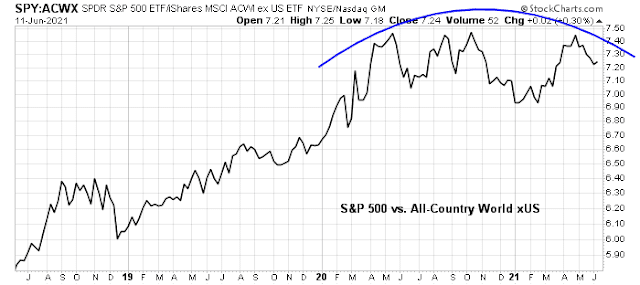

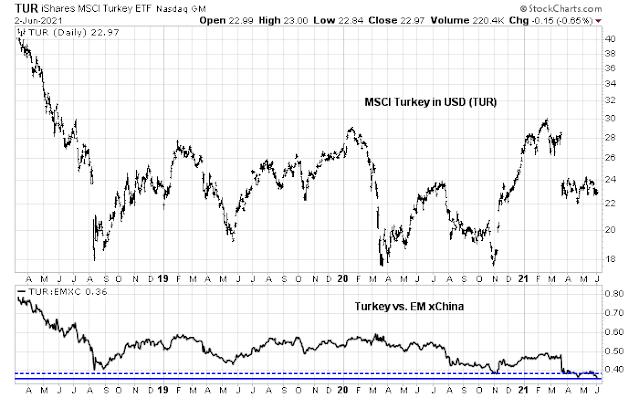

My own market-based indicators appear constructive. The relative performance of MSCI China and the stock markets of China’s major Asian trading partners relative to MSCI All-Country World Index (ACWI) are all showing signs of stabilization. Most markets are holding relative support levels. Taiwan and Australia are exhibiting nascent relative uptrends.

The AUDCAD exchange rate is also a useful market-based indicator of the Chinese economy. Both Australia and Canada are resource-exporting countries of similar size. Despite recent trade frictions, Australia is more sensitive to Chinese growth as most of her exports are either to China or the Asia-Pacific Rim, which are levered to China. By contrast, Canadian trade is more sensitive to the US economy.

AUDCAD recently bounced off an important technical support level after peaking in March. I interpret this as another sign that the trajectory of Chinese economic deceleration is bottoming.

Another reason for greater stability in Asia is the buffer provided by foreign exchange reserves. Bloomberg report that Asian EM FX reserves have grown significantly, which makes them more resilient to external shocks.

Asia’s emerging economies have accumulated their highest level of foreign-exchange reserves since 2014, offering a powerful buffer against market volatility if the U.S. Federal Reserve changes course. Central bank holdings of foreign currencies in the region’s fast-growing emerging economies hit $5.82 trillion as of May, their highest since August 2014. When China’s cash pile is stripped out, emerging Asian central banks’ reserves stood at an all-time high of $2.6 trillion. In 2013 a signal that the Fed would begin winding down asset purchases sent shockwaves through Asia, an episode that came to be known as the “Taper Tantrum.” Foreign investors fled and bond yields shot up, forcing central banks to burn through their defenses to protect their currencies.

The Fed’s hawkish turn

The FOMC took a hawkish turn at its meeting last week. Its

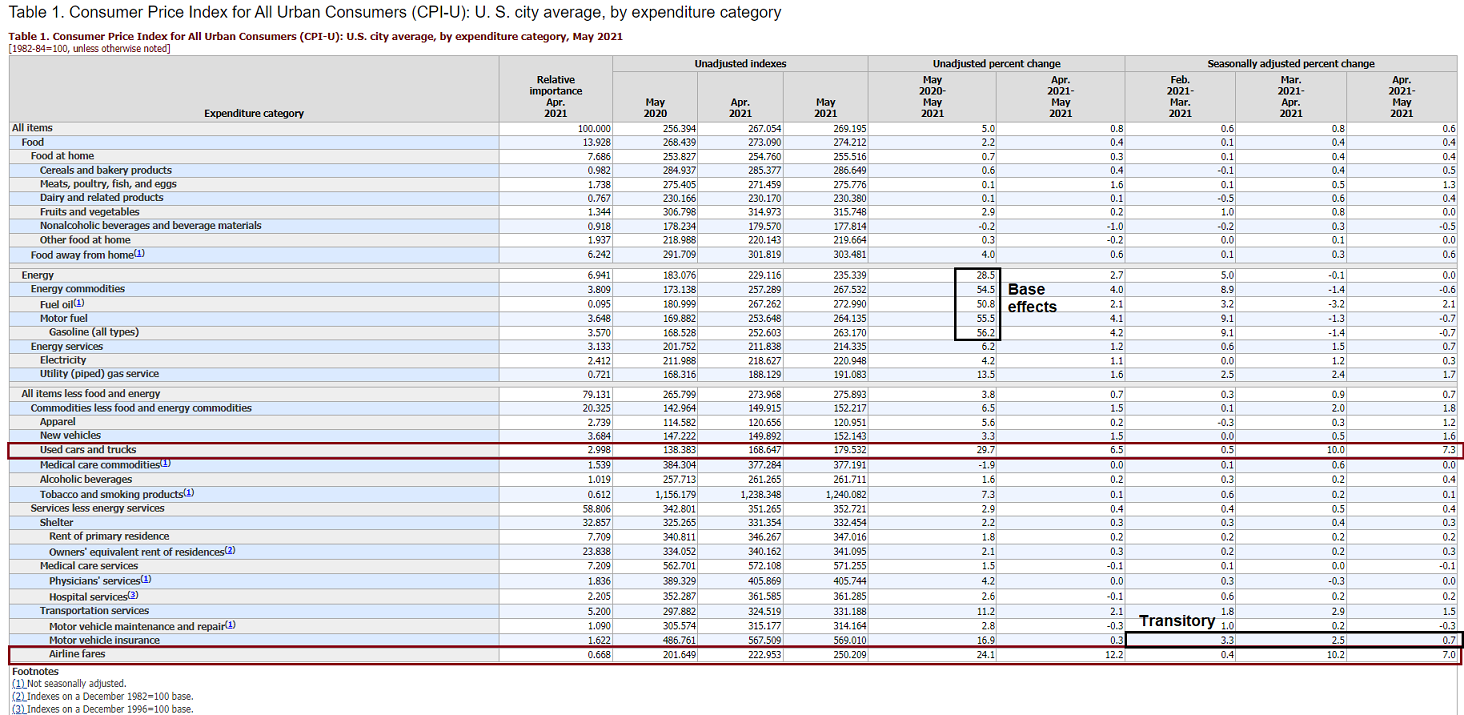

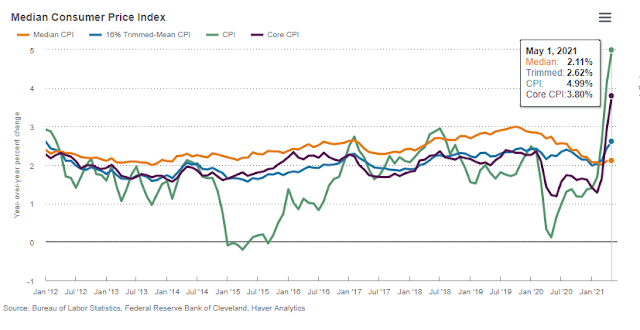

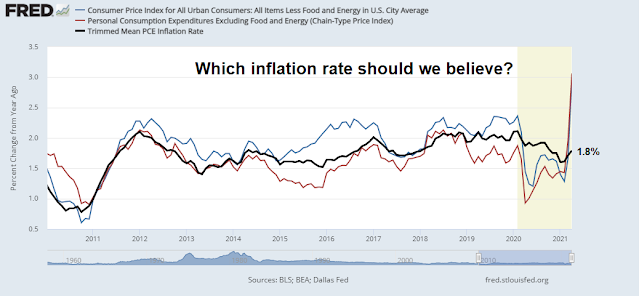

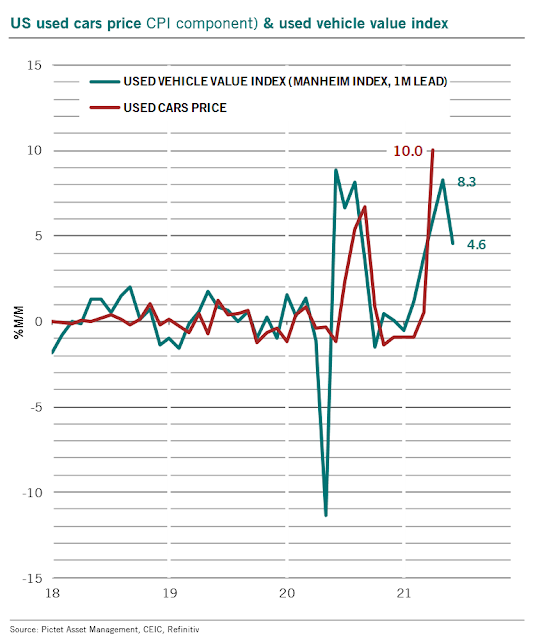

Summary of Economic Projections showed that participants significantly marked up the 2021 inflation rate, regardless of how it’s measured. However, inflation is expected to decline next year indicating the transitory nature of the price increases. Moreover, it is now expecting two rate hikes in 2023, compared to none in the March SEP.

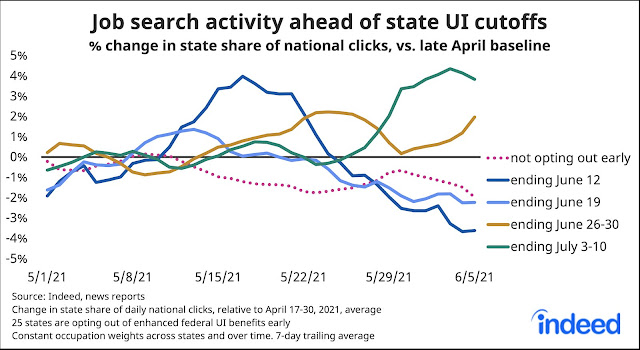

Translated, the Fed believes that pandemic-related downside risks to the economic recovery are falling. It’s seeing signs of transitory inflation. While it’s difficult to forecast policy very far out, it would be prudent to begin removing monetary accommodation and think about raising rates in about two years.

The economy is recovering and gaining momentum, it’s time to gradually take the foot off the monetary accelerator. The Citi Economic Surprise Index, which measures whether economic releases are beating or missing expectations, is rising again after bottoming out recently.

Across the Atlantic, the Eurozone ESI recovered strongly in the second half of 2020 and momentum is strong. The ECB has also signaled that it intends to stay accommodative for a very long time.

These are signs that the rest of the world has decoupled from China and fears of a China slowdown were not dragging down the global economy.

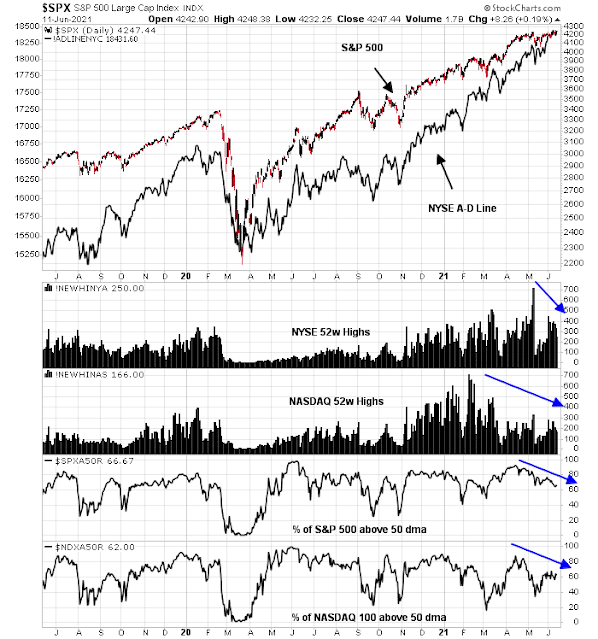

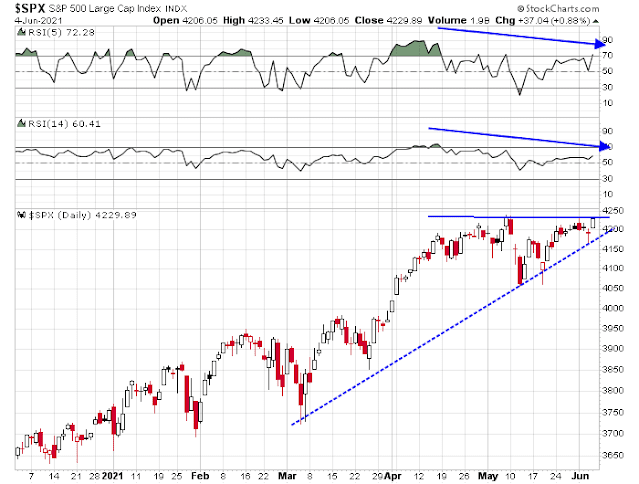

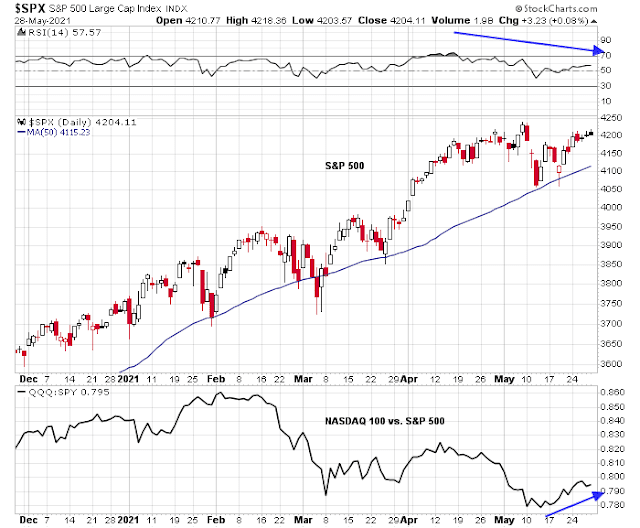

Equity market implications

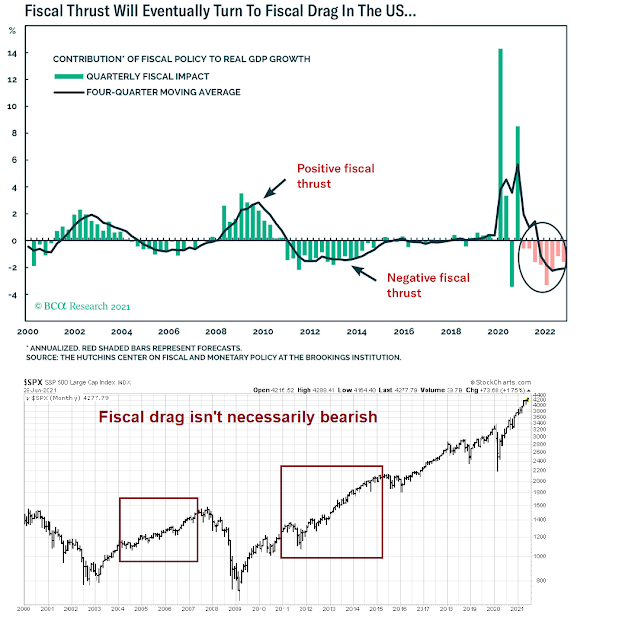

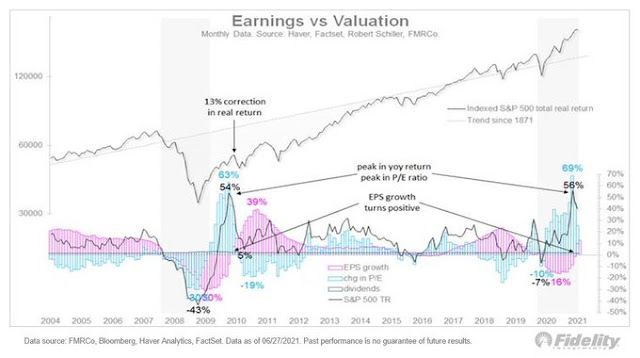

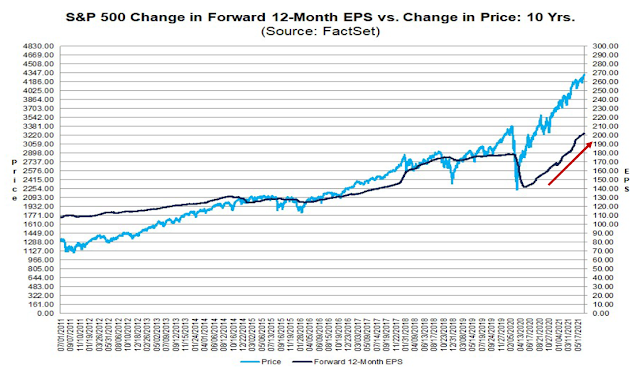

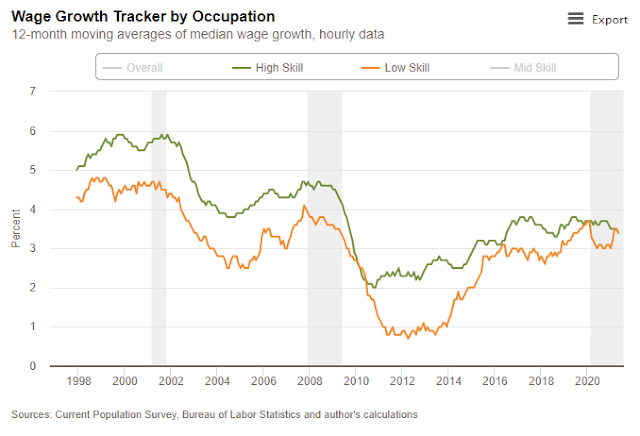

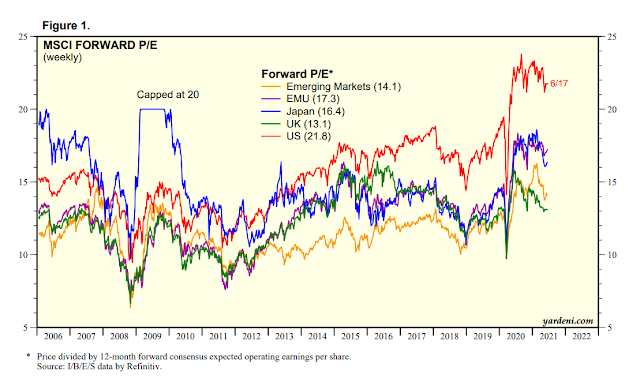

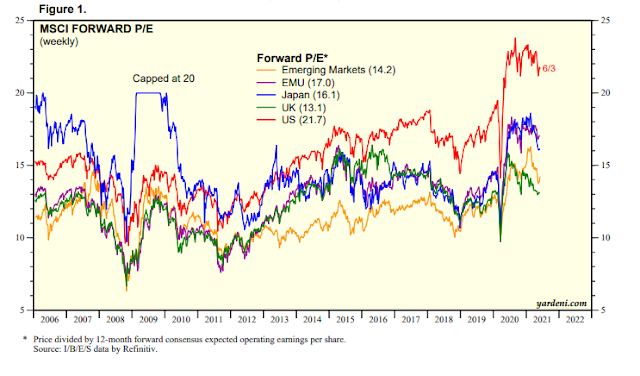

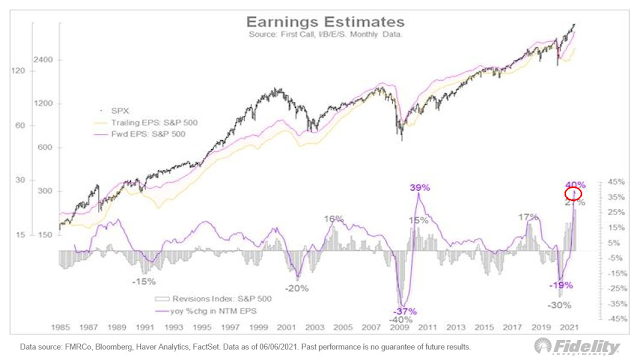

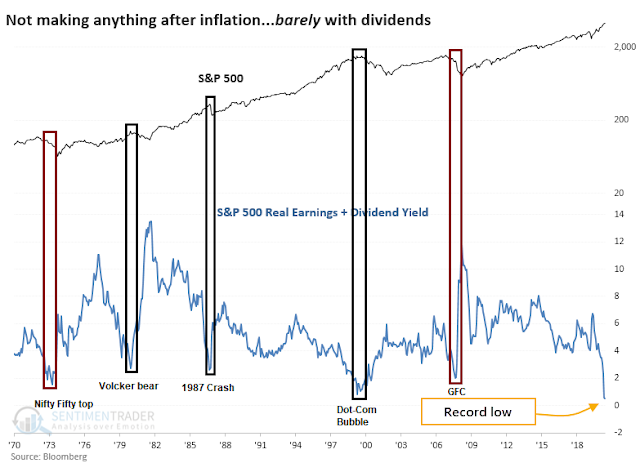

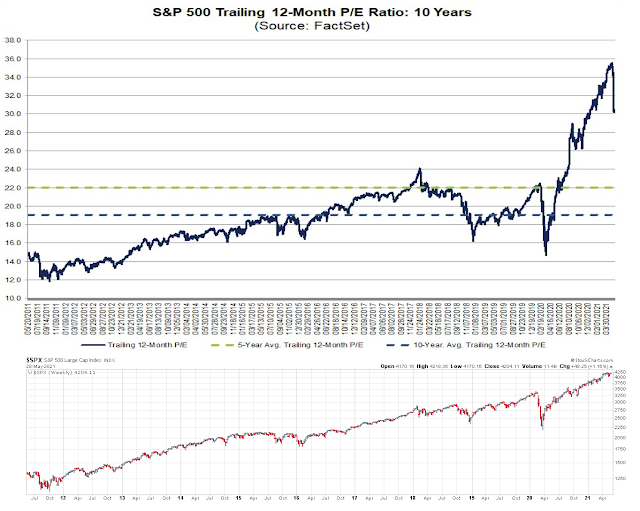

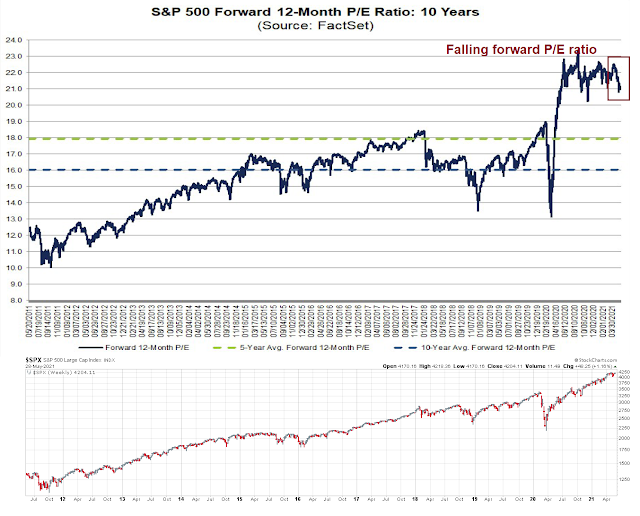

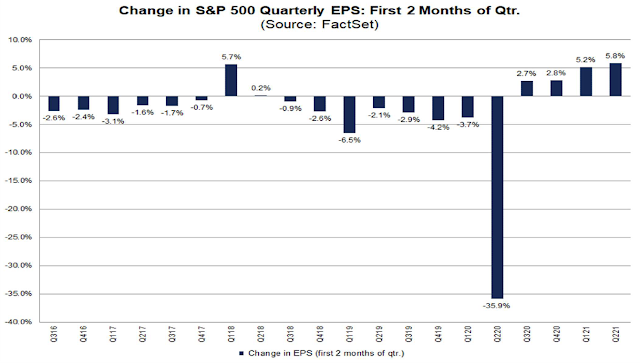

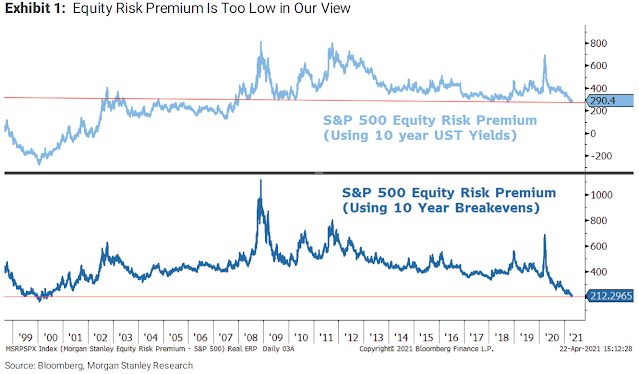

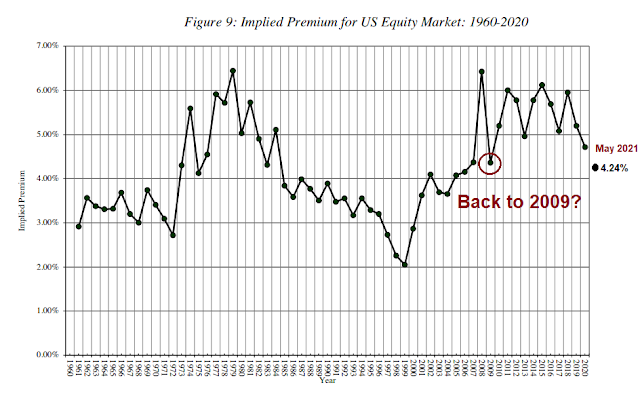

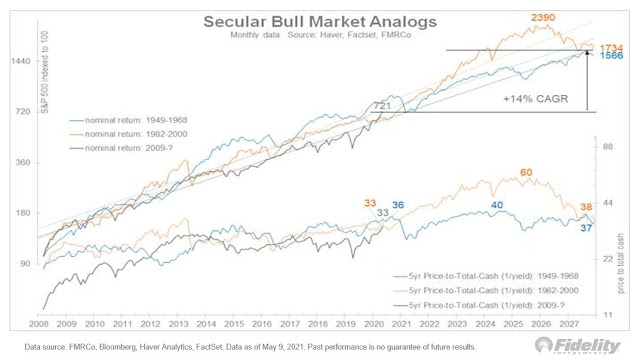

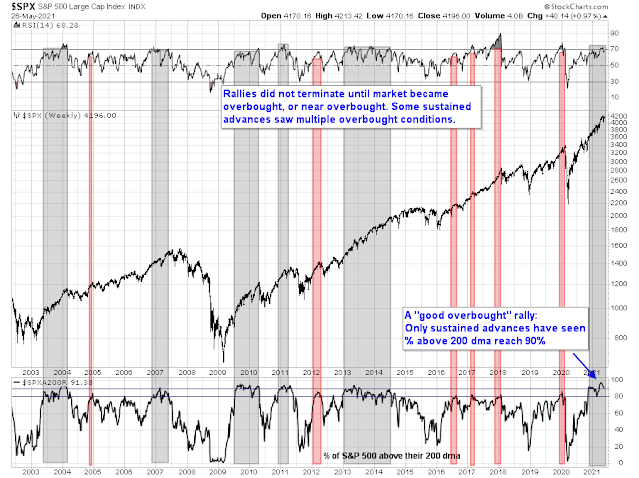

Here is what it means for the equity markets. Market valuation depends on two factors, the P/E ratio, which is a function of interest rates, which are expected to rise, and the E in the P/E, which is also rising too.

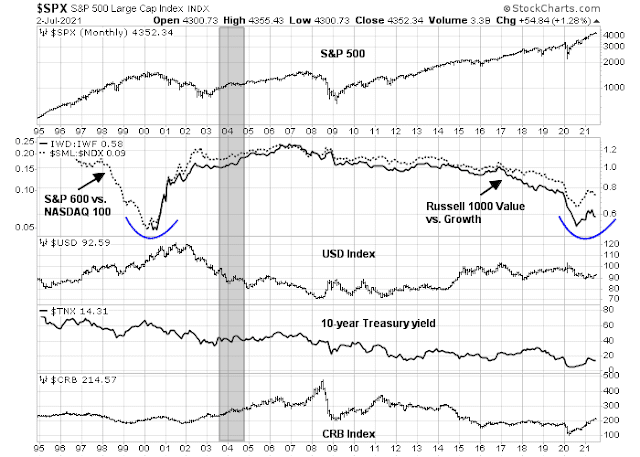

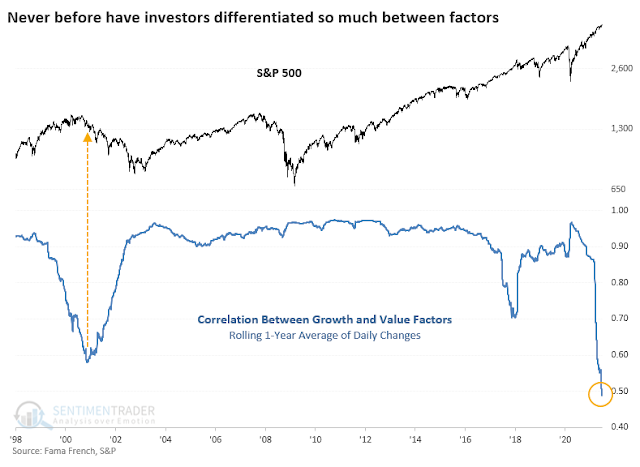

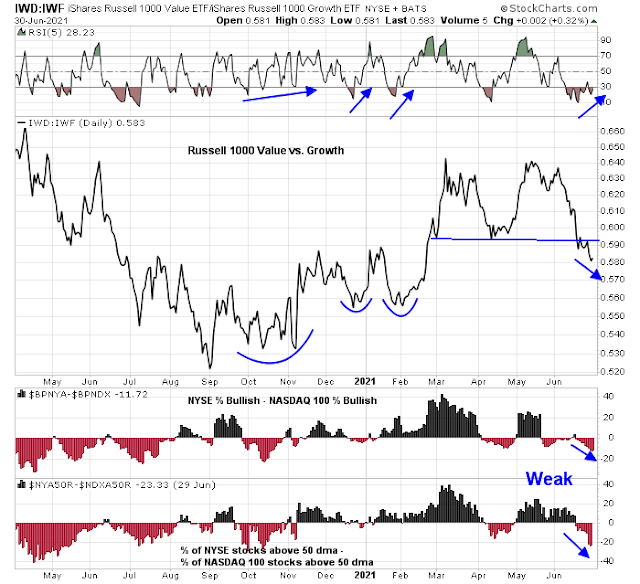

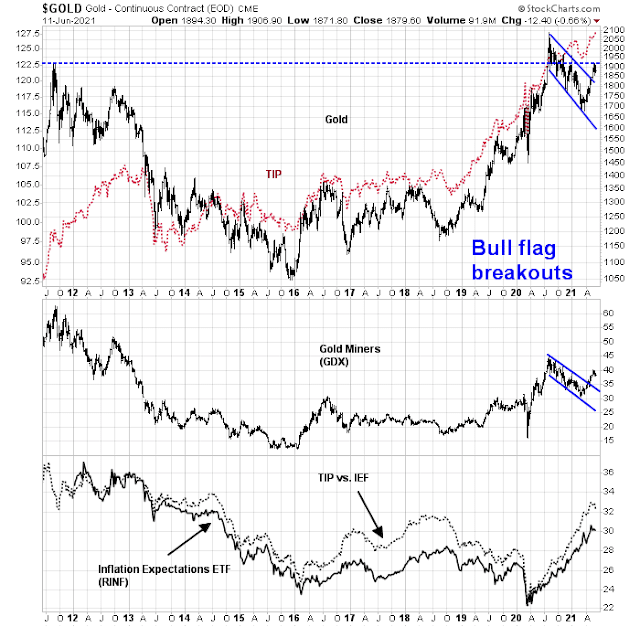

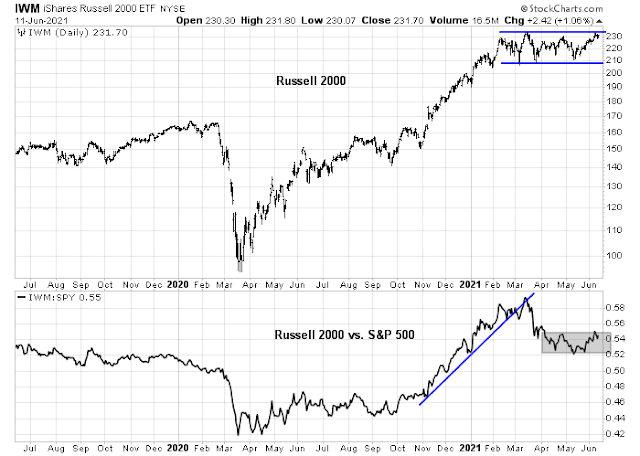

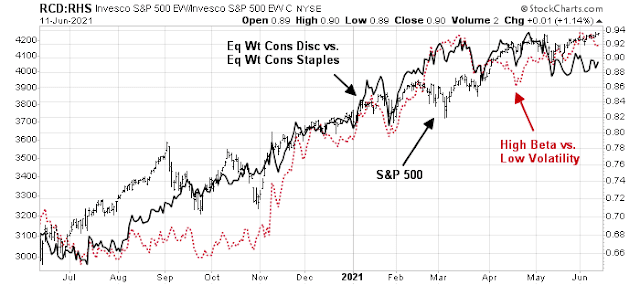

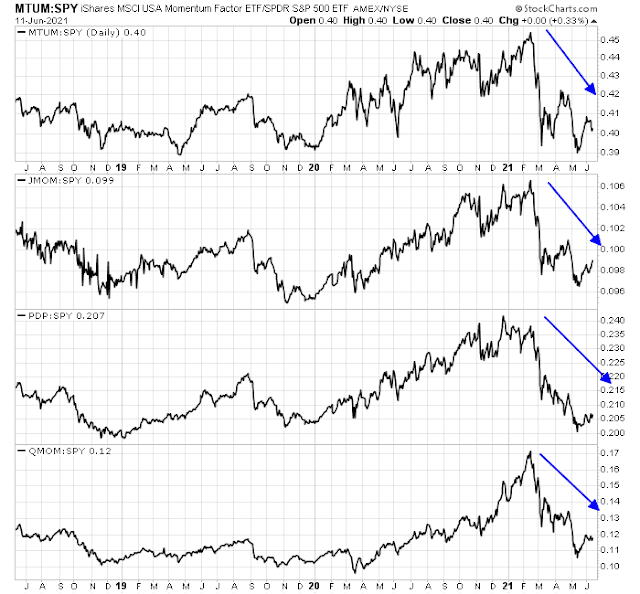

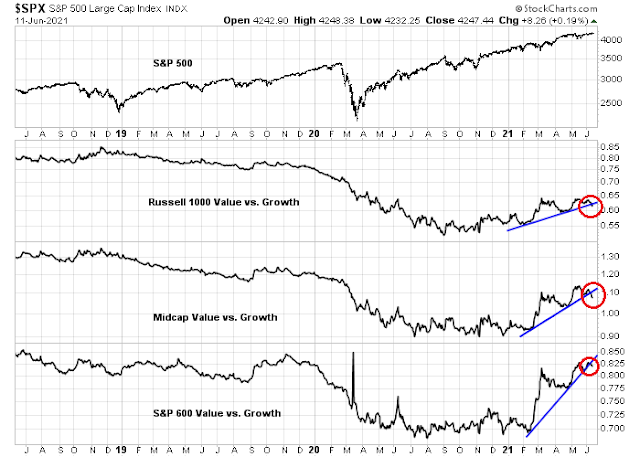

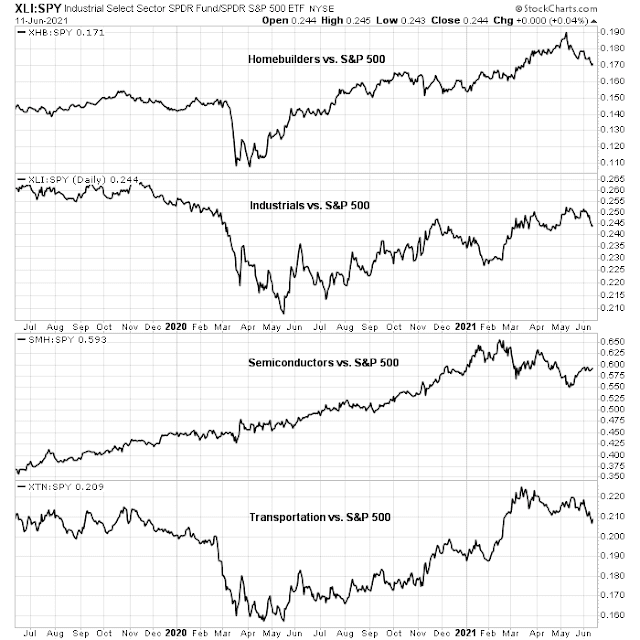

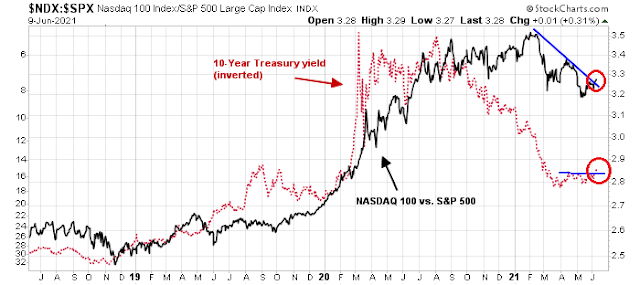

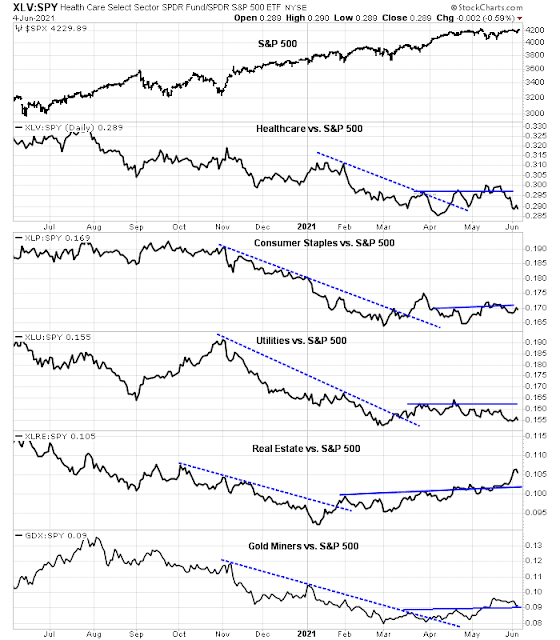

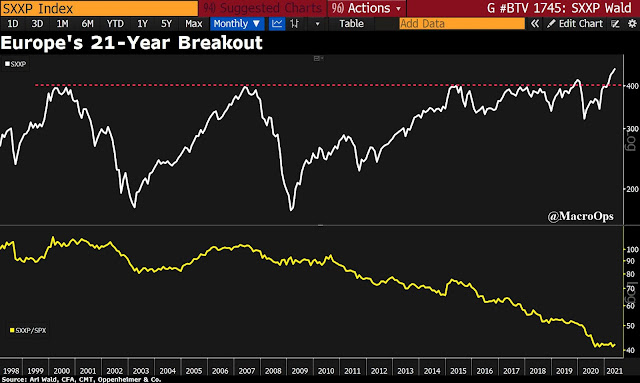

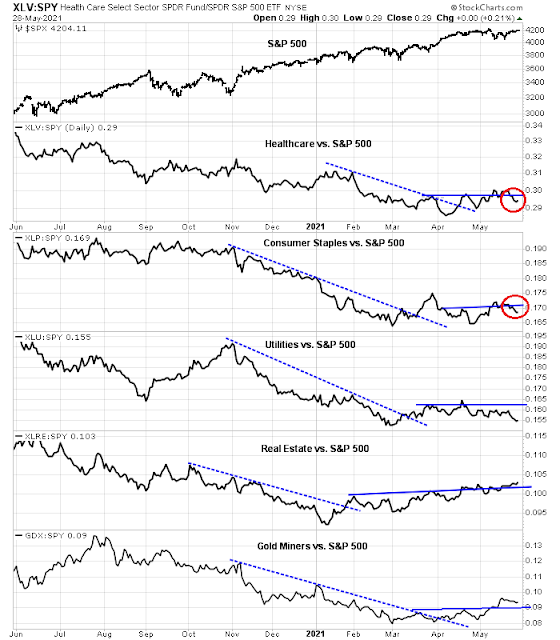

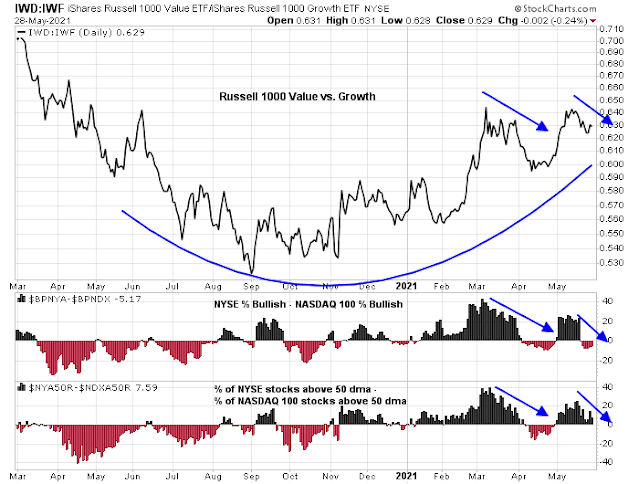

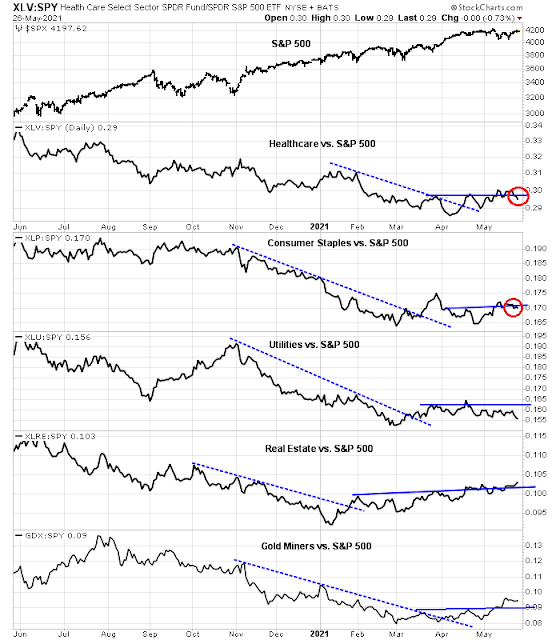

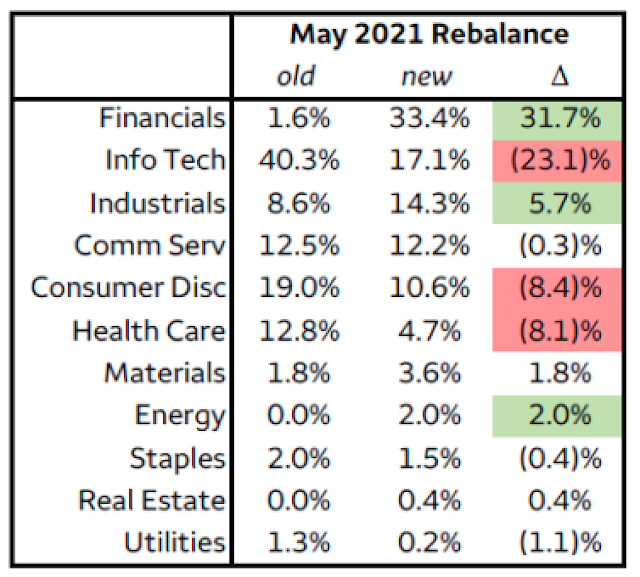

This environment should be bullish for cyclically sensitive equities. The Rising Rates ETF (EQRR), which is tilted toward cyclical and value stocks, is testing a key relative rising trend line. While I would not suggest investing EQRR because of its low AUM which invites a wind-up of the ETF, it is nevertheless a useful barometer of market factor trends.

In particular, I would focus on the commodity-producing parts of the market. PICK is a global mining ETF that is just testing its long-term uptrend.

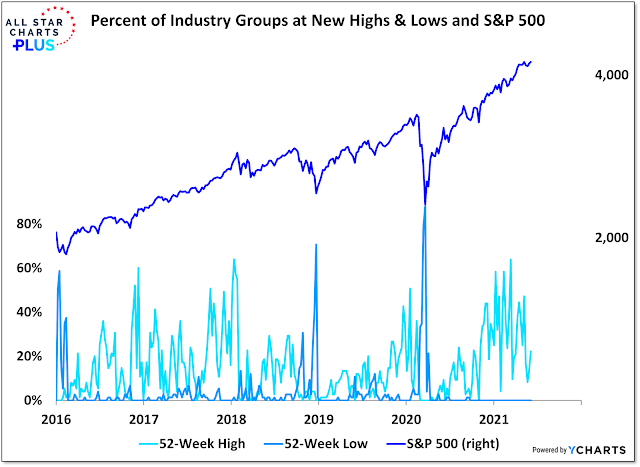

Energy stocks are also exhibiting both absolute and relative uptrends with strong underlying breadth.

There are several reasons to be bullish on these stocks. First, they exhibit cheap relative valuation.

These stocks are also enjoying the tailwind of strong demand-supply fundamentals. The

WSJ reported that there is little current capacity available to meet rising demand from a global recovery.

Languishing commodity prices led producers to slash capital spending on major resources by nearly half over the last decade, shrinking stocks of industrial metals to two-decade lows and reducing supplies across commodities. The crunch is now converging with a buying spree in key markets to supercharge prices—and there is no quick fix.

Since 2011, investments to develop the energy and mining sectors have fallen 40%, according to asset manager Schroders, leaving many producers unprepared for a recent boom in manufacturing and spending in the world’s two largest economies. Prices of resources from corn to lumber to battery metals have risen sharply over the past year, in many cases to twice or more from pre-pandemic levels, aided by low interest rates, a weaker dollar and infrastructure building in the U.S. and China.

Normally, producers respond to higher prices by increasing supply. In this cycle, mining and energy capital expenditures have languished. In particular, the energy sector is cautious about expanding capacity when forecasts call for falling demand as users shift to renewables.

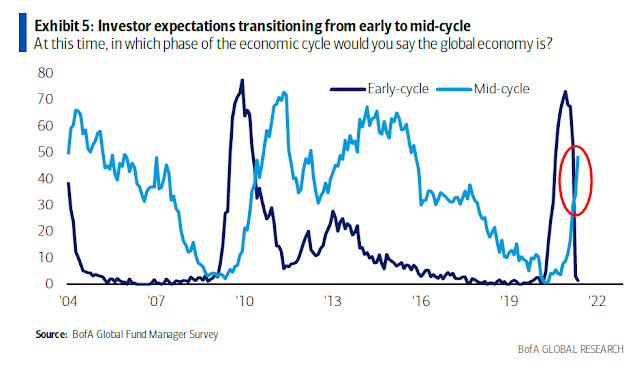

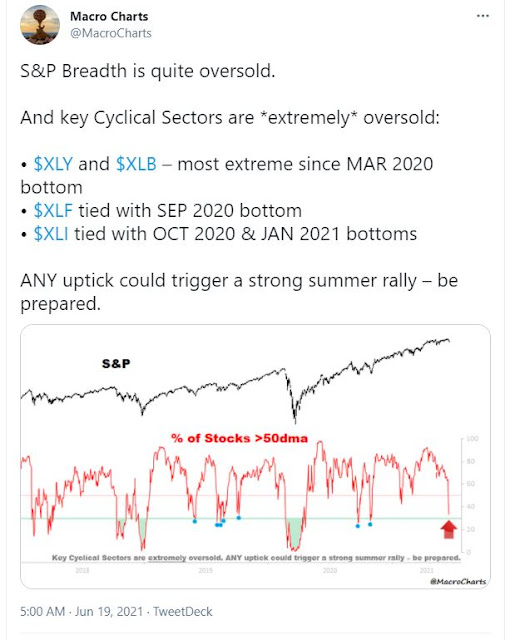

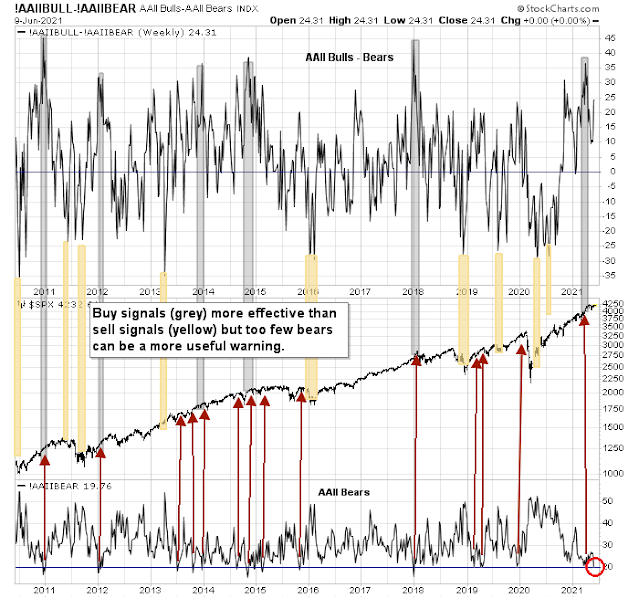

In the short-term, however, investors are already overweight the cyclical and reflation trade. The latest BoA Global Fund Manager Survey shows that respondents are overweight commodities, banks, and cyclically sensitive sectors like industrials. If a pullback were to occur, investors should regard that as a welcome sentiment reset to gain cyclical exposure.

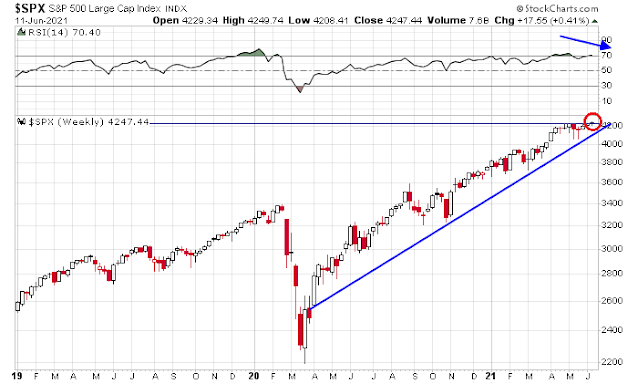

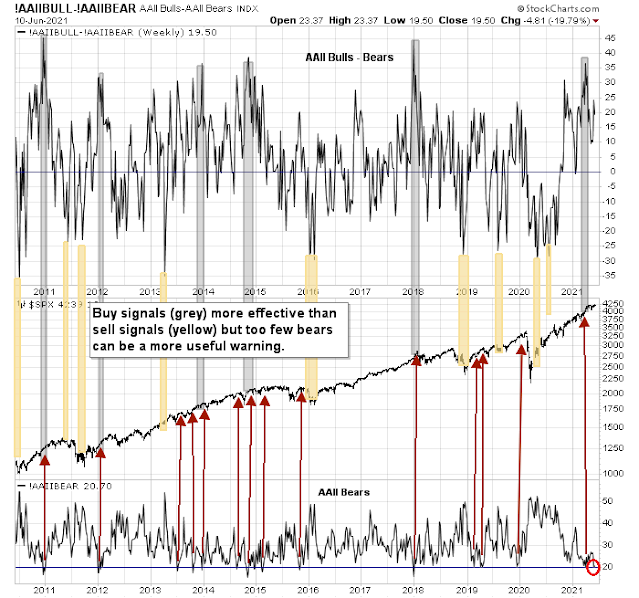

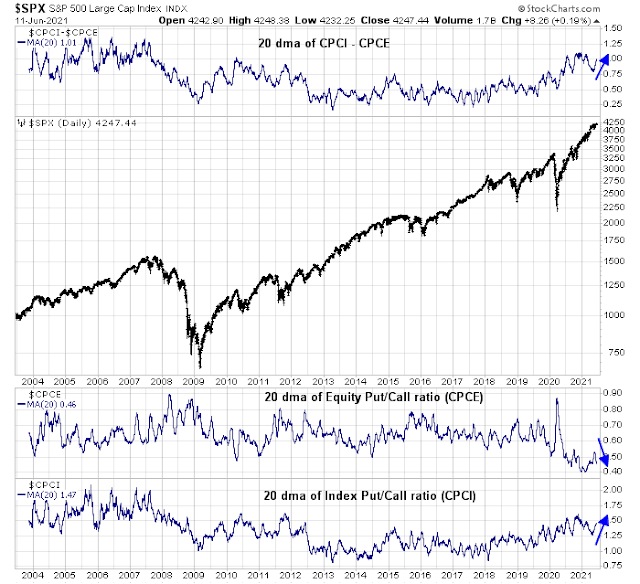

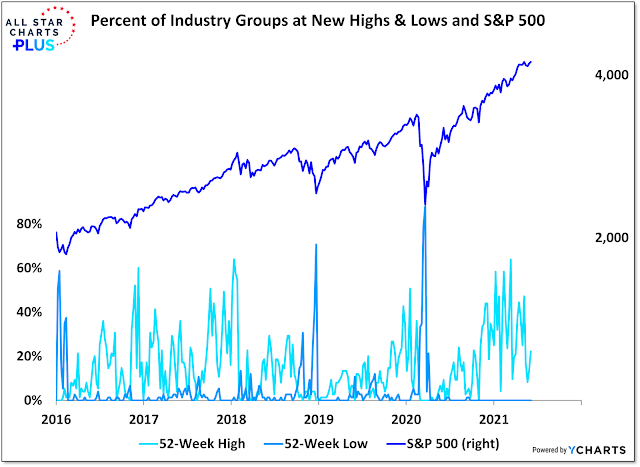

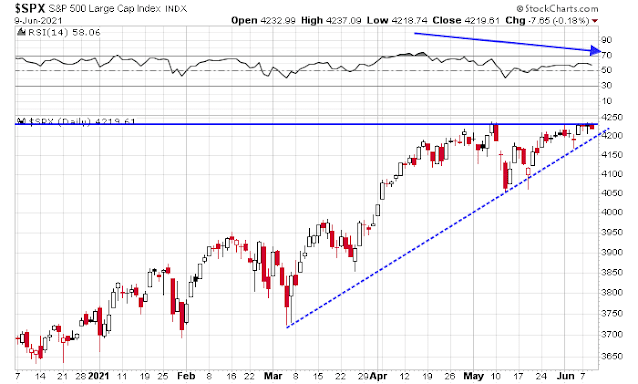

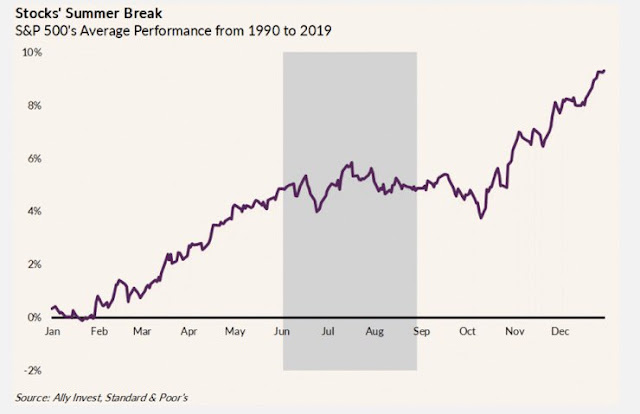

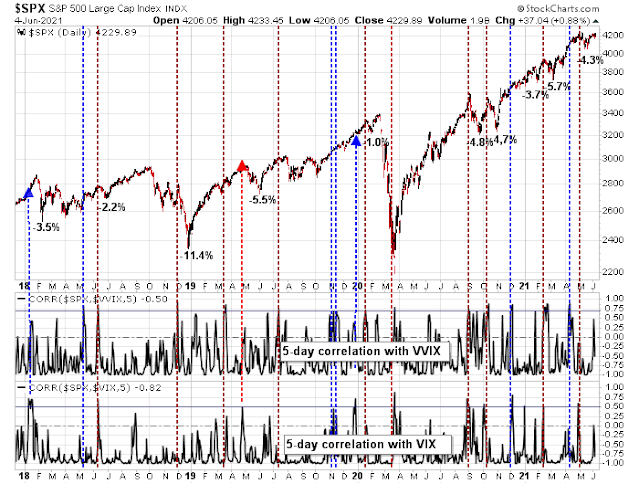

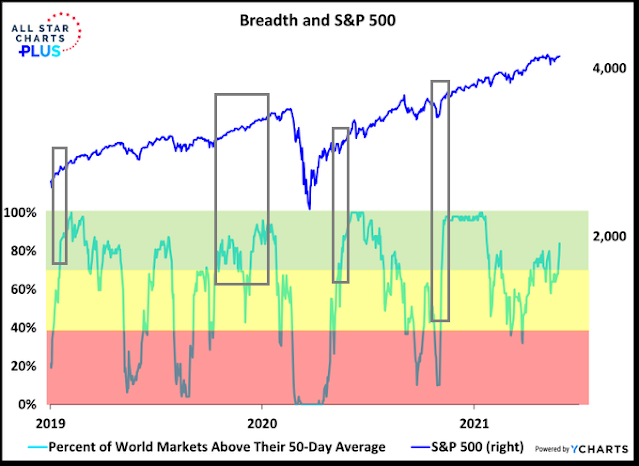

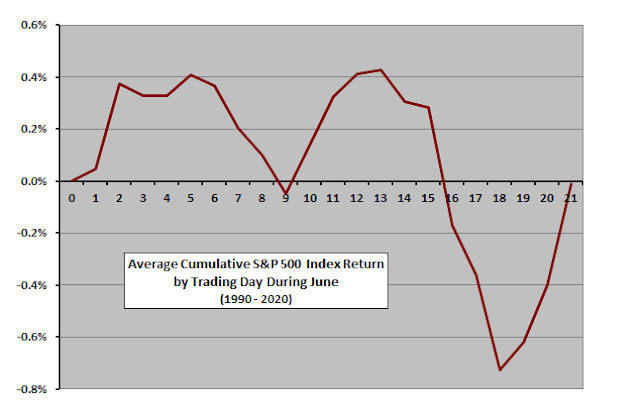

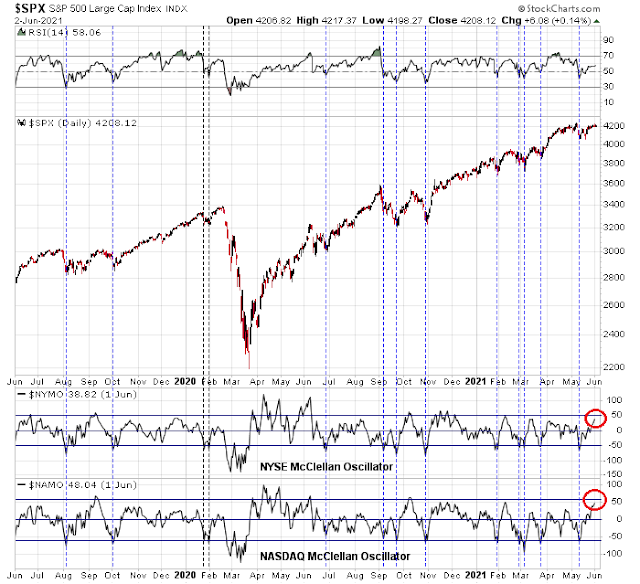

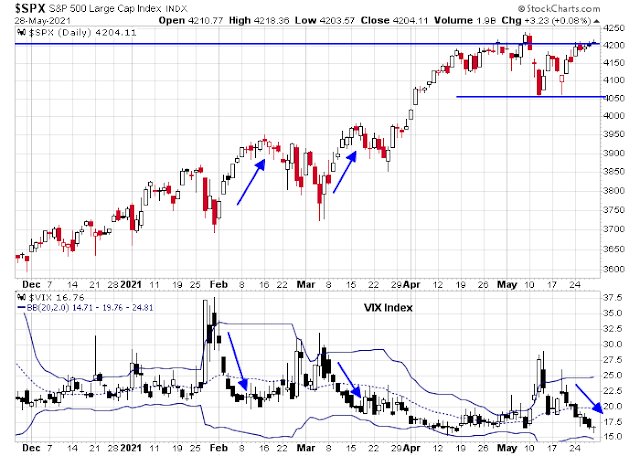

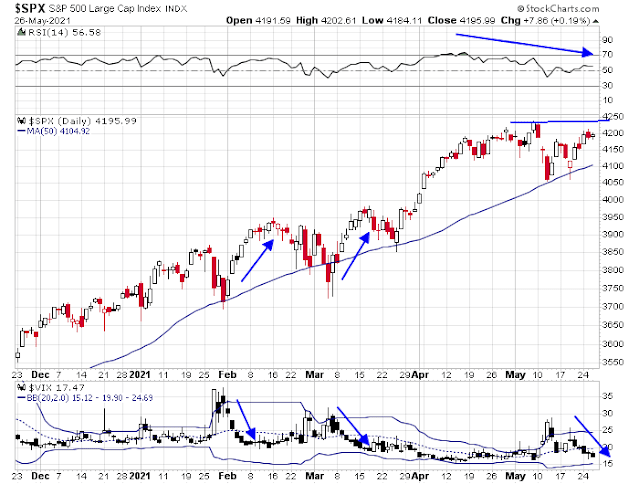

No market crash

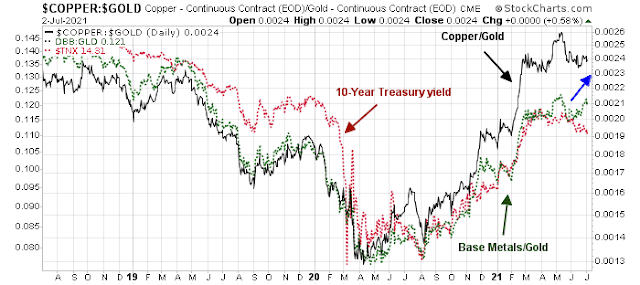

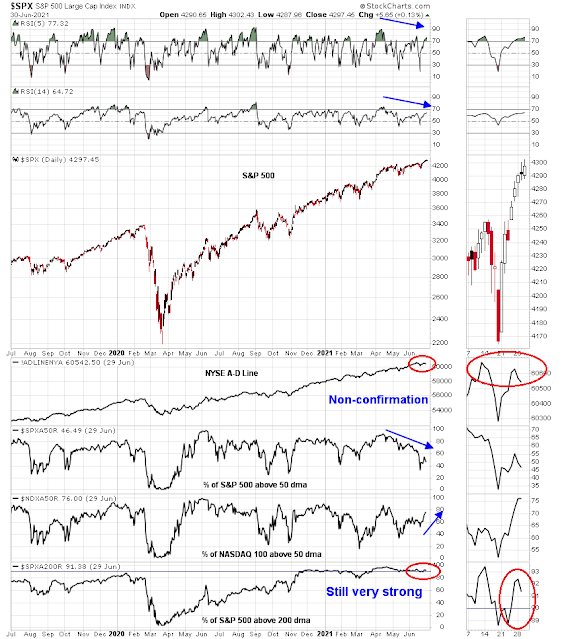

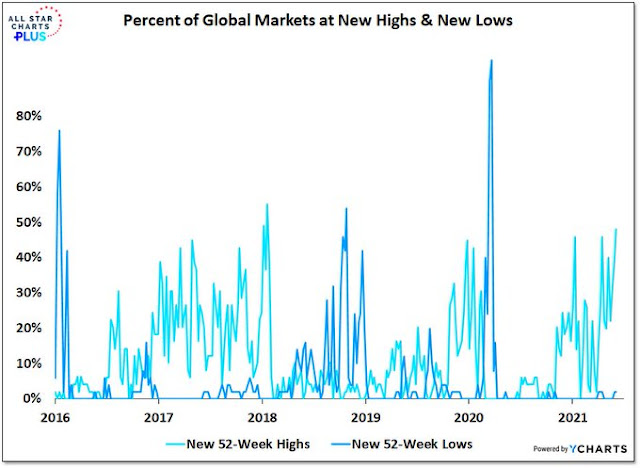

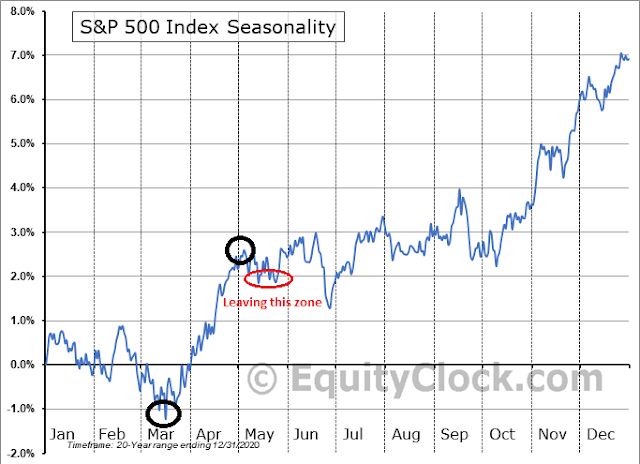

In conclusion, investors should not expect the stock market to crash despite the dire headlines. Real-time indicators such as the copper/gold and the broader base metals/gold ratios indicate a sideways pattern in risk appetite. This should not lead to a major risk-off episode.

From an intermediate-term perspective, the current environment is bullish for cyclical and reflation stocks, and especially resource extraction sectors owing to the lack of a supply response in the face of rising demand. Signs of stabilization and a possible bottom in China’s growth trajectory will also be supportive of commodity demand, as China has been the primary consumer of global commodities. However, investors are already long the cyclical and reflation investment theme, and a pullback would represent a buying opportunity.