Explaining our market timing models

We maintain several market timing models, each with differing time horizons. The “Ultimate Market Timing Model” is a long-term market timing model based on research outlined in our post Building the ultimate market timing model. This model tends to generate only a handful of signals each decade.

The Trend Model is an asset allocation model which applies trend following principles based on the inputs of global stock and commodity price. This model has a shorter time horizon and tends to turn over about 4-6 times a year. In essence, it seeks to answer the question, “Is the trend in the global economy expansion (bullish) or contraction (bearish)?”

My inner trader uses the trading component of the Trend Model seeks to answer the question, “Is the trend getting better (bullish) or worse (bearish)?” The history of actual out-of-sample (not backtested) signals of the trading model are shown by the arrows in the chart below. Past trading of this model has shown turnover rates of about 200% per month.

The signals of each model are as follows:

- Ultimate market timing model: Buy equities

- Trend Model signal: Risk-on (upgrade)

- Trading model: Bullish

Update schedule: I generally update model readings on my site on weekends and tweet any changes during the week at @humblestudent. Subscribers will also receive email notices of any changes in my trading portfolio.

The bulls are back in town

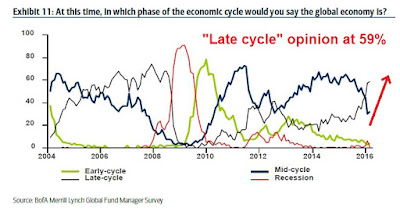

In the last few weeks, I had been writing about a transition to a late-cycle market. The latest results from the BoAML Fund Manager Survey show that 59% of institutional managers believed that we are in the late-cycle phase of the expansion cycle. The 59% figure is the highest reading since August 2008.

A late-cycle expansion is characterized by tightening capacity, falling unemployment, rising wage and other inflationary pressures, which are ultimately followed by tight monetary policy.

The current macro environment is indeed seeing signs of tighter employment and modest inflationary pressures. A couple of months ago, the markets had been wrongly focused on the risks of impending recession. We are now seeing a reversal and a FOMO (fear of missing out) reflationary rally in stock and commodity prices.

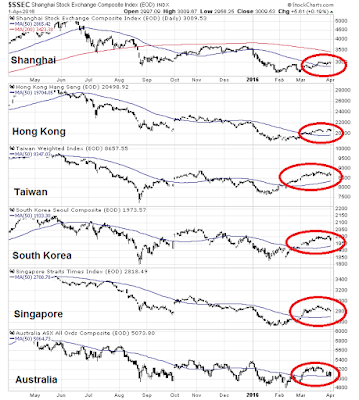

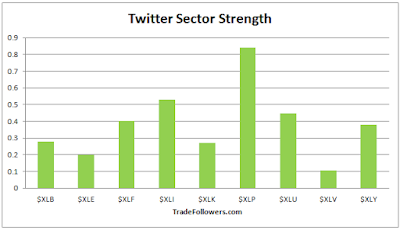

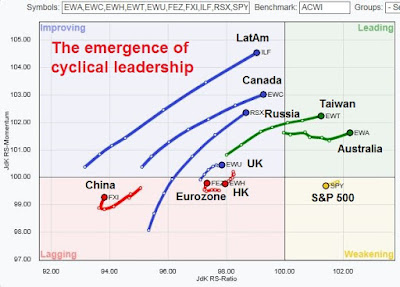

Indeed, sector leadership is displaying the classical signs of a late cycle rotation. A review of Relative Rotation Graphs (RRG), which depict the evolution of market group rotation where group leadership rotates in a clockwise fashion, shows that at cyclical rotation continues at a health pace at a global level. The chart below shows RRG relative to MSCI All-Country World Index. Resource sensitive countries and regions such as Australia (bulk commodities), Canada (commodities), Latin America (commodities), Russia (oil) and Taiwan (semiconductors) are either market leaders or becoming market leaders. By contrast, the developed market regions such as the US, UK and Eurozone are weak by comparison.

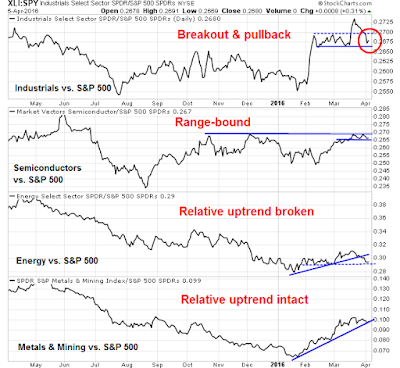

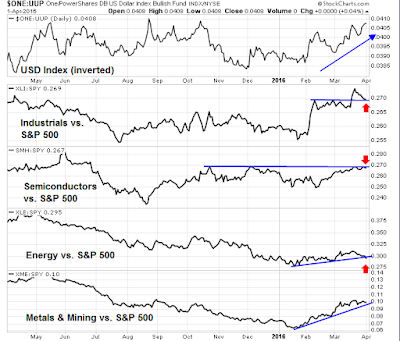

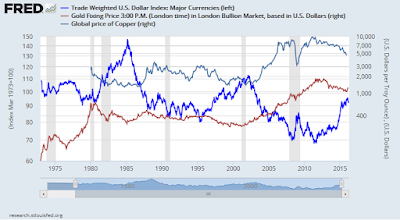

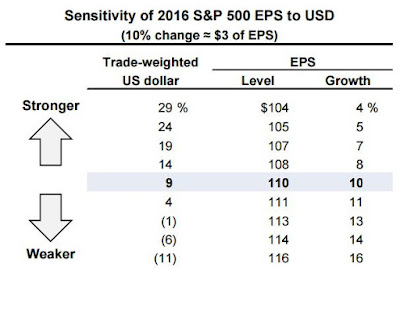

US sector leadership is also telling a similar story. The chart below shows that the USD (top panel) is weakening, which fuels inflationary pressures. Moreover, cyclically sensitive groups such as industrial stocks, representing capital goods manufacturers, semiconductors and resource extraction industries have all bottomed and now turning up against the market.

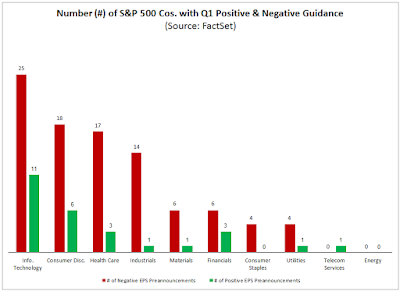

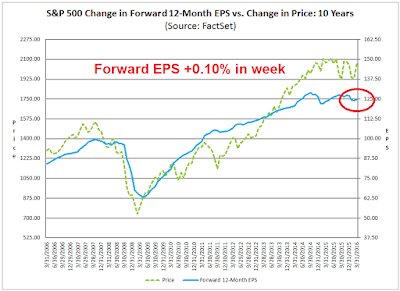

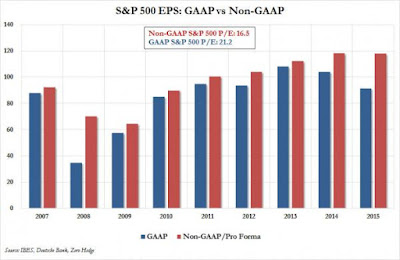

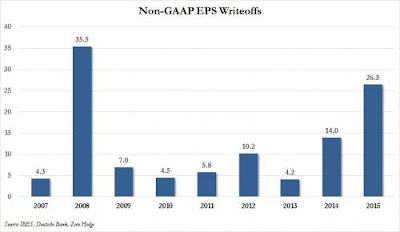

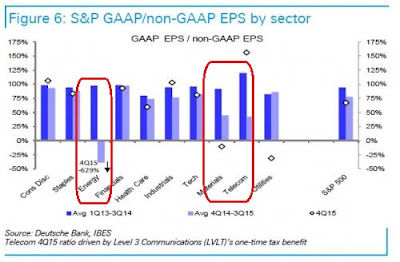

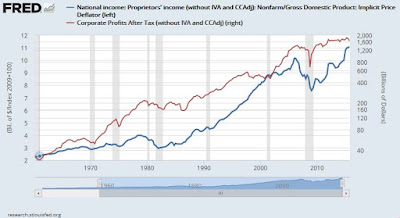

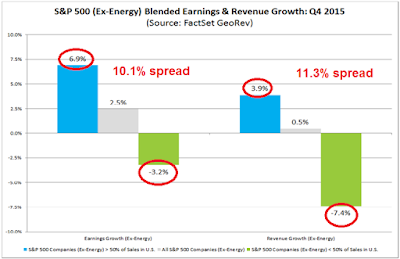

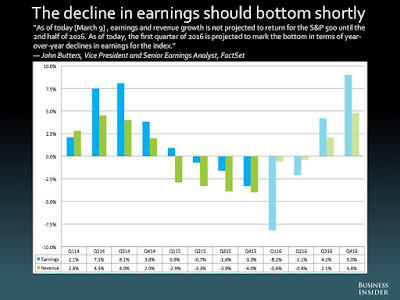

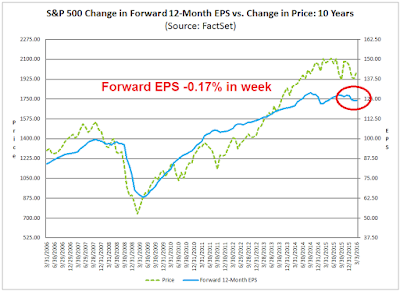

Business Insider reports that John Butters of Factset believes that a cyclical upturn is just around the corner. In other words, earnings growth have gotten so bad that the outlook is good:

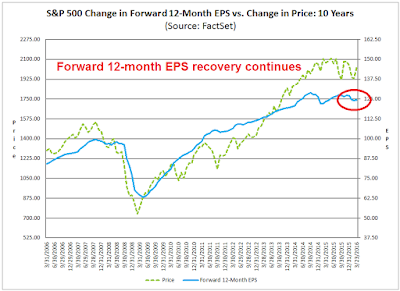

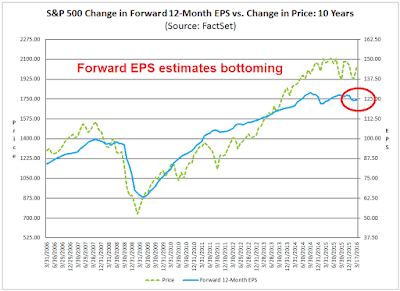

Indeed, his latest update shows that forward 12-month EPS bottoming and starting to turn up again.

Watching for signs of a market top

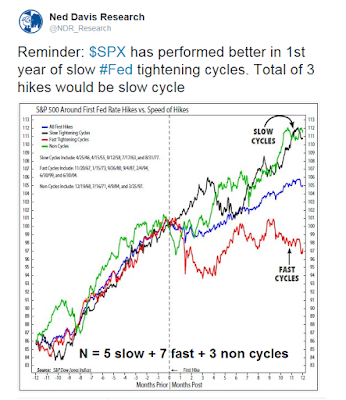

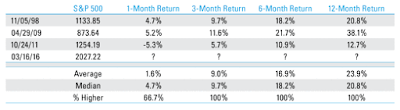

Even though the term “late cycle” connotes the late stages of a bull market, the historical evidence suggests that stock prices may have further upside before an ultimate top is reached. I present a couple of case studies of how past market tops have formed during similar late cycle expansionary episodes, with the usual caveat that history doesn’t repeat itself, but rhymes.

The market top of 1980-81 was a classic case of late cycle, inflationary blow-off market top. The chart below shows the price of gold (blue line) as a proxy for inflationary expectations and the Russell 1000 (red line) as a proxy for stock prices. Gold peaked out in January 1980, partly as a reaction to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in late 1979. Gold did not fall immediately, but took about nine months to form a double top. At the same time, stock prices did not peak out until soon after the second gold top. As a reminder, this price action occurred in the era of the extremely tight monetary policy of the Volcker Fed.

We can see a similar pattern in the market top of 1990. Gold prices showed the double top pattern that it did in 1980. While the 1980 experience saw stock prices rise significantly during the gold double top period, stock prices were flat to slightly up in the 1990 gold double top episode.

I have several takeaways from this analysis. First, during this topping process, equities did not decline significantly until the second gold top. As we have not even seen the first gold top yet, history tells us that the risk of a major bear market starting in the immediate future is relatively low.

The historical pattern also suggests that these kinds of late cycle episodes take roughly a year to play themselves out. As we are still very early in the pattern, this is not time to panic (yet). However, it is a warning for investors to start watching for signs of market deterioration in the forms of macro, fundamental or technical weakness. So far, there is little in evidence of pending weakness.

I would add that the market tops of 2000 and 2007 did not display similar kinds of cyclical behavior and therefore this analytical framework is not applicable to those market tops. Moreover, I am also not implying that a war is just around the corner as it was in 1980 (Soviet invasion of Afghanistan) and 1990 (Iraqi invasion of Kuwait). However, Alex Kazan of Eurasia Group did recently pointed out that measures of global political risk is rising, most notably in the emerging market economies (via Business Insider).

The Fed throws a party

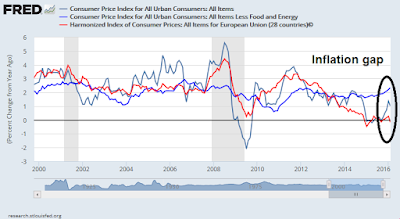

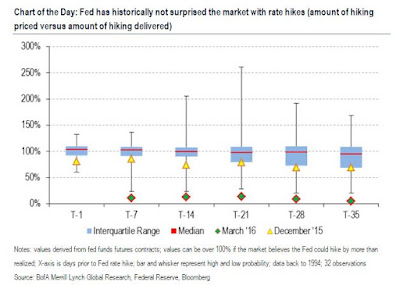

Meanwhile, the Fed threw a party last week. The one big surprise last week was the dovish stance taken by the FOMC. The guiding principles of the Phillips Curve, which postulates a short-term inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation, seemingly went out the window. Instead, the Yellen Fed focused on the downside risk posed by the weakness in global economy. The Fed seemed to have changed its mandate from central banker to the United States to central banker to the world.

The change in tone at the Fed prompted a cacophony of criticism about the dangers of inflation (see Macro Man for an example of the shrillness of the pushback). This Ambrose Evans-Prichard article entitled “The Yellen Fed risks Faustian pact with inflation” is a more reasoned exposition of the Fed’s policy risk:

It is clear that the US Federal Reserve is now trapped. The FOMC dares not tighten despite core inflation reaching 2.3pc because it is so worried about tantrums in financial markets and about that other Sword of Damocles – some $11 trillion of offshore debt denominated in dollars, up from $2 trillion in 2000.

The Fed has been forced by circumstances to act as the world’s central bank, nursing a fragile and treacherous financial system struggling with unprecedented leverage.

Average debt ratios are 36 percentage points of GDP higher than they were at the top of the pre-Lehman bubble in 2008, and this time emerging markets have been drawn into the quagmire as well by the spill-over effects of quantitative easing. Like it or not, the Fed is stuck with the task of cleaning up a global mess that is arguably of its own making.

Evans-Pritchard went on to warn about the risk of getting behind the curve as inflation ticks up:

[Yellen] admitted that the US economy is “close to our maximum employment objective”, meaning that it is near the inflexion point of NAIRU (non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment), where unemployment is so low that wage pressures start to gather steam. She admitted too that headline inflation will pick up briskly as the effects of the oil price crash fade from the data. Yet she shrank from her own insights.

The deeper we go into this cycle, the clearer the risk of a policy mistake. Broad U6 unemployment is dropping very fast and has reached 9.7pc, which may be equivalent to the 8pc lows of the last cycle given the notorious mismatch in job skills. The labour ‘quit rate’ is soaring as workers feel confident enough to switch jobs and push for better pay.

In the end, the Fed may have to resort to a series of “nasty staccato hikes” that are faster than anyone expects, which would push the economy into recession:

Stimulus is building up. The bonanza from cheap oil – worth $1,000 a year for average households, says Mrs Yellen – is accumulating in bank accounts and has yet to be spent. The fiscal austerity of recent years is giving way to a net fiscal boost worth 0.5pc of GDP in 2016 as state and local governments stoke spending.

Mrs Yellen acknowledges the dangers. She knows that the Fed could be forced into a series of nasty staccato hikes if it waits too long now – the time-honoured cause of past recessions – yet the FOMC continues to take a calculated risk that it can navigate these reefs, that a dovish course is the lesser of evils.

In the end, while the dovish tone of the FOMC was a surprise at a tactical level, the long-term script remains the same. In the late cycle phase of an expansion, capacity tightens in both manufacturing and employment, which creates inflationary pressures. Commodity prices rise. The Fed ultimately responds by raising rates at a rapid rate, which pushes the economy into recession. This period also coincides with the double top in gold prices that we have seen in the past. The only missing variable is the timing of the tightening cycle.

For now, we haven’t even seen the first gold top yet. So let’s party.

The week ahead: Waiting for pullback

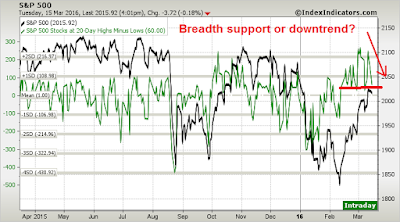

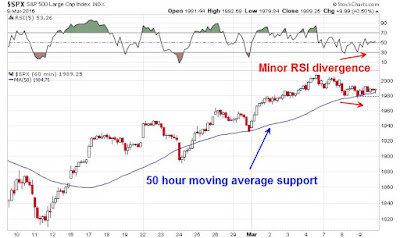

Looking to the week ahead, the dovish FOMC statement last week poured gasoline on the bullish fires and stocks saw another leg up, despite the fact that it began last week in an overbought condition.

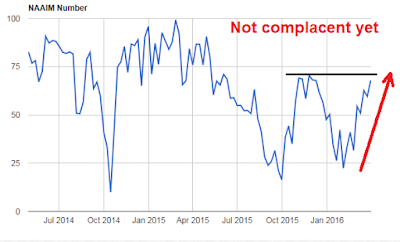

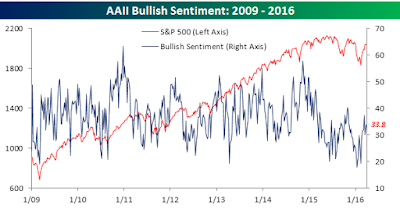

Nevertheless, I am starting to see cautionary signs. The CNN Money Fear and Greed Index is showing a high level of greed. The stock market has experienced difficulty advancing during past episodes. The big question is, “Could we be seeing a repeat of the failed rally of last October and November?”

Insiders are pulling back from their pattern of aggressive buying. With the caveat that weekly readings are noisy, the latest update of insider activity from Barron’s indicates that this group of “smart investors” have toned down their purchases of their own company`s stock that has been in place since last November. Their behavior is an eerie repeat of their activity seen during the last stock market rally.

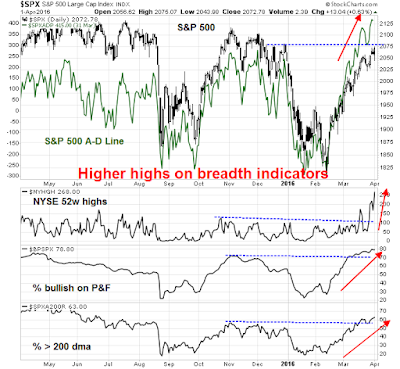

Both the current market and the market seen last Oct/Nov are overbought in a similar fashion. As the chart below shows, the SPX is experiencing a series of “good” overbought readings on RSI-5, which is a typical characteristic of breadth thrusts. Moreover, RSI-14 is reaching levels where the market pulled back after the last breadth thrust episode in October 2015.

While some market weakness is quite likely next week, here is what I am watching for to distinguish between an ordinary minor correction/consolidation and a period of more serious price weakness. As the above chart shows, the relative performance of junk bonds rolled over as the market topped out. This was a warning sign that risk appetite was weakening. The behavior of the junk bond market will be an important indicator of the health of the current rally.

I am also watching how market leadership evolves. The market leadership of NASDAQ stocks rolled over during the consolidation period last November. The relative performance of the current leadership, namely the cyclical stocks, will also be an important “tell” of the future direction of stock prices in the near future.

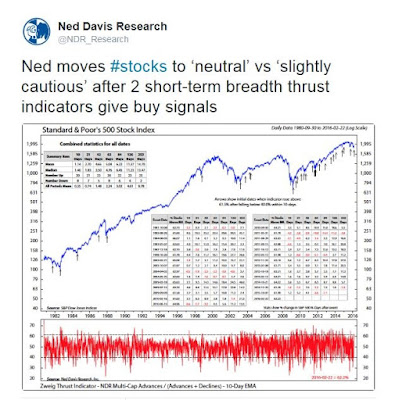

There are reasons to be optimistic. Tom McClellan observed that the Ratio Adjusted Summation Index (RASI) is showing sufficient strength to rise about the +500 level even after fall below that in the most recent sell-off. This is an indication of underlying breadth strength and his conclusion was the current advance has further room to run.

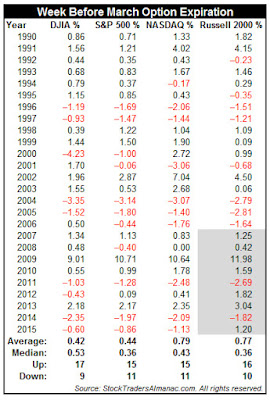

In addition, Urban Carmel highlighted analysis from the Stock Trader`s Almanac that when the market experiences a positive reaction to an FOMC meeting, it typically sees a minor top in the following week, pulls back, and then rises to further highs.

My inner investor is enjoying the party. He had bought stocks on weakness, with an overweight position in the resource extraction sectors.

My inner trader was in cash during the move last week as he was unwilling to roll the dice on the FOMC meeting. He is waiting for the likely pullback next week and watching the market internals before making a decision on whether to buy or not.