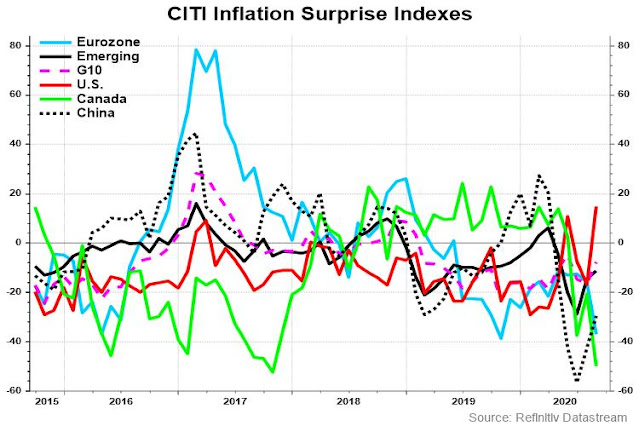

It has been over a week since Jerome Powell’s virtual Jackson Hole speech in which he laid out the Fed’s revised its updates to its Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy after a long and extensive internal review. There were two changes. one was a shift towards an “average inflation targeting” regime, where the Fed “seeks to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time”. The other was an emphasis on to target low unemployment. Instead of minimizing “deviations from the maximum” employment, it will minimize “shortfalls of employment from its maximum level.”

The results of the review were much like a student handing in a term paper after much effort, but the assignment is incomplete, and leaves many questions unanswered.

- How will the Fed calculate the average inflation rate? In other words, what decision rules will the Fed adopt to raise interest rates?

- How credible is the 2% inflation target? How does the Fed expect to raise the inflation rate, when it was unable to do so for many years? Is it because its lab partner, fiscal policy, failed to work on the assignment?

- How will the Fed manage the bond market’s expectations? If the average inflation target of 2% is credible, how far above 2% will the 10-year Treasury yield be, and what will that do to the economy and stock prices?

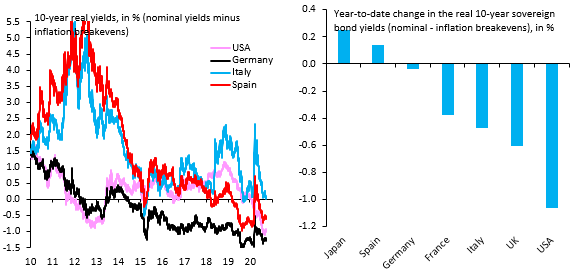

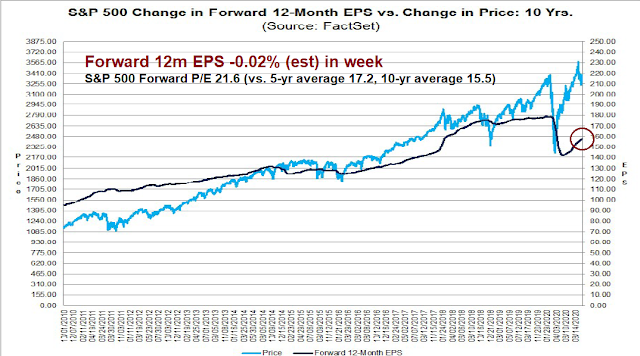

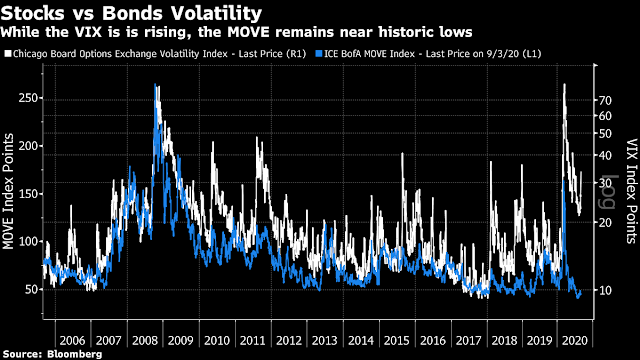

On the last point, I had a discussion with a reader about the implications for the bond market in the wake of Powell’s speech. Wouldn’t a credible 2% average inflation target translate into a substantial surge in bond yields? How far above 2% does the 10-year Treasury have to trade? What does that mean for equity valuations?

Supposing that you knew for certain that inflation will average 2% over the next 10 years, you would certainly demand a Treasury yield of over 2%, say 2.5%. The 10-year yield needs to rise by at least 1.8%. What would that do to the economy, and the stock market?

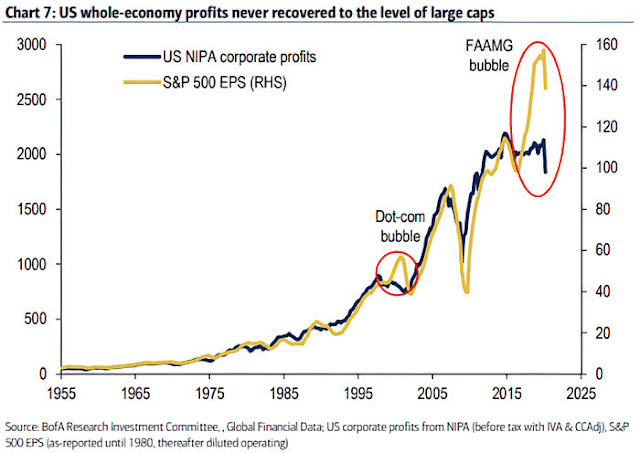

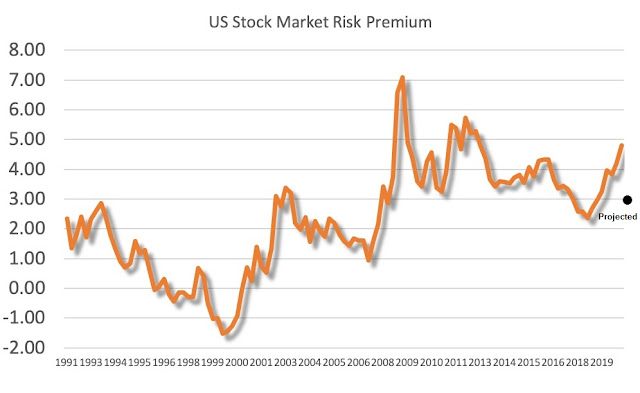

Forward P/E ratios are stratospheric compared to their own history, but some investors have justified the high multiple by pointing to low rates. TINA, or There Is No Alternative. Valuations are reasonable based on equity risk premium (ERP), which is some variation of E/P – interest rates. Here is the Q2 2020 ERP calculation of Antonio Fatas, professor of economics at INSEAD. While the stock market appears reasonably priced based on ERP today, raising rates by 1.8% (everything else being equal) would make stocks far less attractive compared to fixed income alternatives.

Something doesn’t add up. The Fed’s review appears incomplete. There are too many unanswered questions.

Wild confusion

The Fed needs to work on its communication policy. Reuters reported that, one day after the Powell speech, regional Fed presidents had wildly differing interpretations of what the average inflation target policy meant.

Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan said he would be comfortable with inflation running a “little bit” above the Fed’s 2% inflation target if the economy were to once again be running near full employment.

“And for me, a little bit means a little bit,” or about 2.25%, Kaplan said during an interview with Bloomberg TV. “I still think price stability is the overriding goal and this framework doesn’t change that.”

St. Louis Fed President James Bullard, who along with Kaplan and their 15 policymaker colleagues will carry out the Fed’s new strategy, had a different answer.

“Inflation has run below target, certainly by half a percent, for quite a while, so it seems like you could run above for a half a percent for quite a while,” Bullard told CNBC.

And Philadelphia Fed President Patrick Harker had yet another view.

“It’s not so much the number. … It’s really about the velocity,” Harker said during a separate interview with CNBC, adding that inflation “creeping up to 2.5%” is different from inflation that is “shooting past 2.5%.”

A subsequent speech by Vice Chair Richard Clarida was equally unclear about the Fed’s plans, other to convey the impression that the FOMC intends to steer monetary policy by the seat of its pants.

To be clear, “inflation that averages 2 percent over time” represents an ex ante aspiration, not a description of a mechanical reaction function—nor is it a commitment to conduct monetary policy tethered to any particular formula or rule.

Fed governor Lael Brainard was equally ambiguous when she described Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT) in a separate speech.

Flexible average inflation targeting is a pragmatic way to implement a makeup strategy, which is essential to arrest any downward drift in inflation expectations.While a formal average inflation target (AIT) rule is appealing in theory, there are likely to be communications and implementation challenges in practice related to time-consistency and the mechanical nature of such rules. Analysis suggests it could take many years with a formal AIT rule to return the price level to target following a lower-bound episode, and a mechanical AIT rule is likely to become increasingly difficult to explain and implement as conditions change over time. In contrast, FAIT is better suited for the highly uncertain and dynamic context in which policymaking takes place.

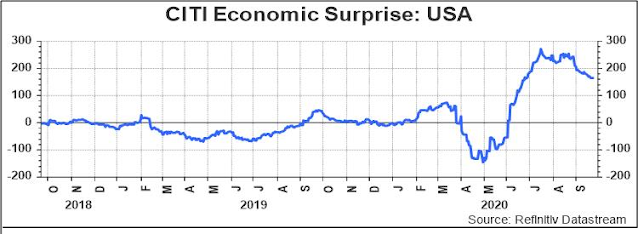

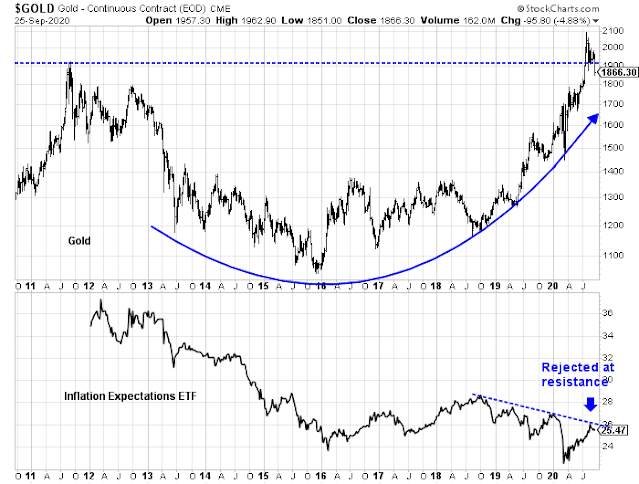

In practice, the new monetary policy framework means that the Fed will be slower to tighten to allow the economy to run “hot” and ensure that inflation rises above 2% and averages at 2%. The key indicator to watch is inflation expectations, which needs to stay anchored at 2%.

The lab partner goes AWOL

After over a decade of sub-2% inflation, the new policy framework does nothing to address how the Fed plans to raise inflation to the 2% average. For that, the central bank needs the cooperation of its lab partner, fiscal policy.

Lael Brainard’s recent speech pleaded for help from fiscal policy as she acknowledged that monetary policy could not do all the heavy lifting by itself.

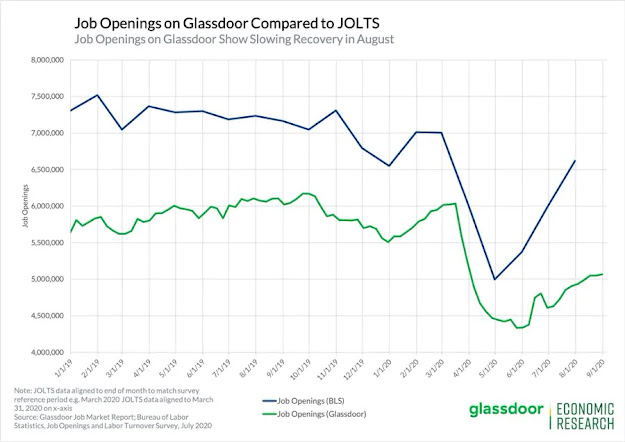

Looking ahead, the economy continues to face considerable uncertainty associated with the vagaries of the COVID-19 pandemic, and risks are tilted to the downside. The longer COVID-19-related uncertainty persists, the greater the risk of shuttered businesses and permanent layoffs in some sectors. While the virus remains the most important factor, the magnitude and timing of further fiscal support is a key factor for the outlook. As was true in the first phase of the crisis, fiscal support will remain essential to sustaining many families and businesses.

In the short run, political gridlock has gripped Washington as both sides have been unable to agree on a CARES Act 2.0 fiscal relief package. In addition, a second important deadline is approaching, as the government faces a shutdown on October 1st in the absence of interim funding legislation. Fortunately, Treasury Secretary Mnuchin and House Speaker Pelosi appear to be agreeable to working together to avoid a government shutdown.

In short, the Fed’s lab partner, fiscal policy, is nowhere to be seen, and the Fed’s policy review is not very meaningful without the partner’s presence.

The Abenomics template

Notwithstanding the short-term battles on Capitol Hill, chances are that policy direction will move towards a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) framework no matter who wins in November. How will that play out?

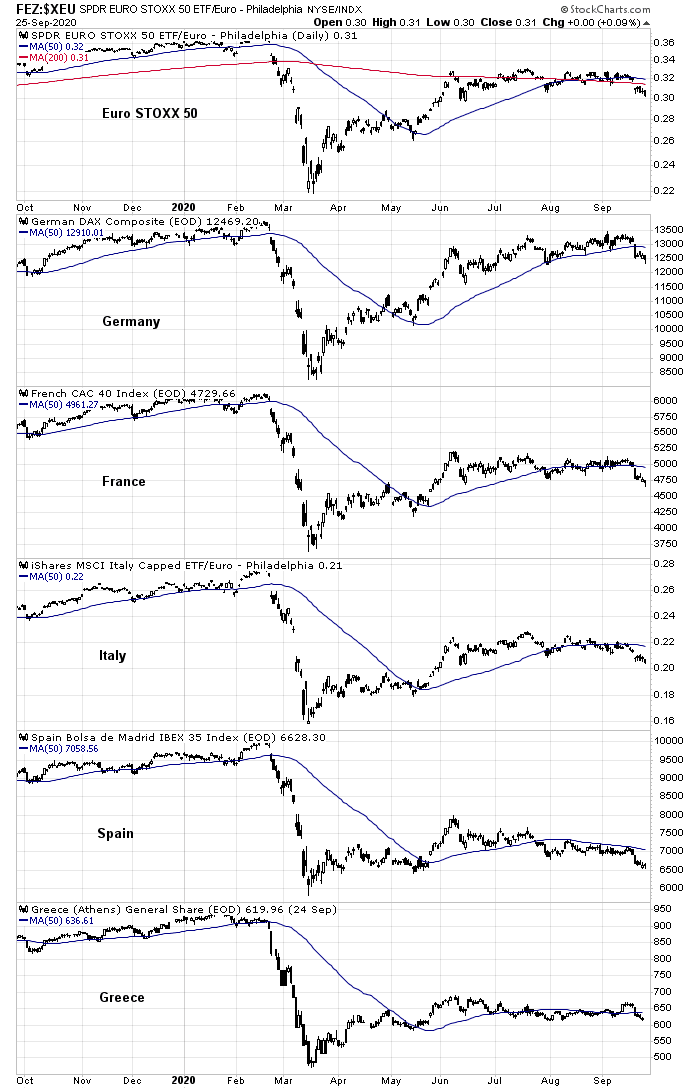

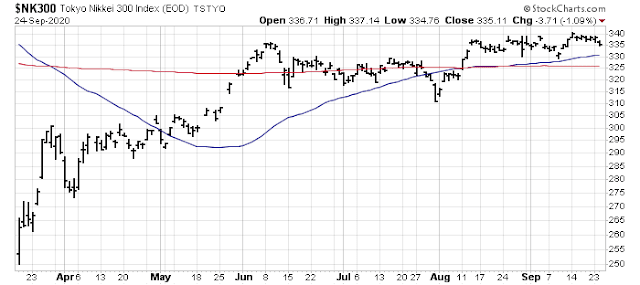

For some clues of how the combination of fiscal and monetary policy might work, we can consider the Abenomics experiment, named after Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, who recently announced his resignation. Abe’s decade-long efforts to halt Japan’s deflation consisted of the “three arrows” of Abenomics, fiscal stimulus, monetary stimulus from the BoJ, and structural reform of the Japanese economy. The results was a mixed bag of successes and failures.

The initial thrust of the BoJ’s aggressive monetary policies briefly pushed the CPI inflation above 3%. But loose monetary policy was offset by tight fiscal policy, as the government imposed a sales tax increase. So much for inflation.

Despite the decline in headline CPI inflation, inflationary expectations rose, which was constructive.

Abenomics was also able to partially revive capital expenditures.

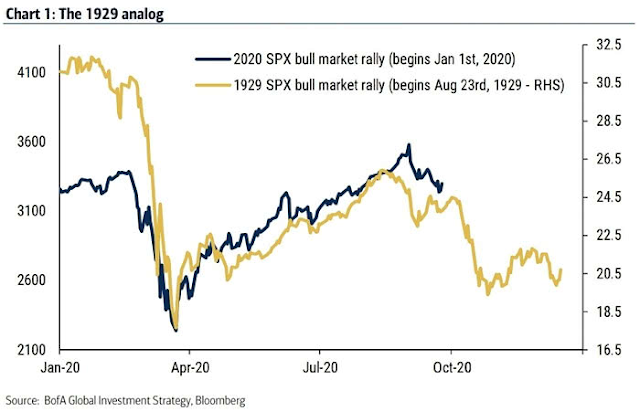

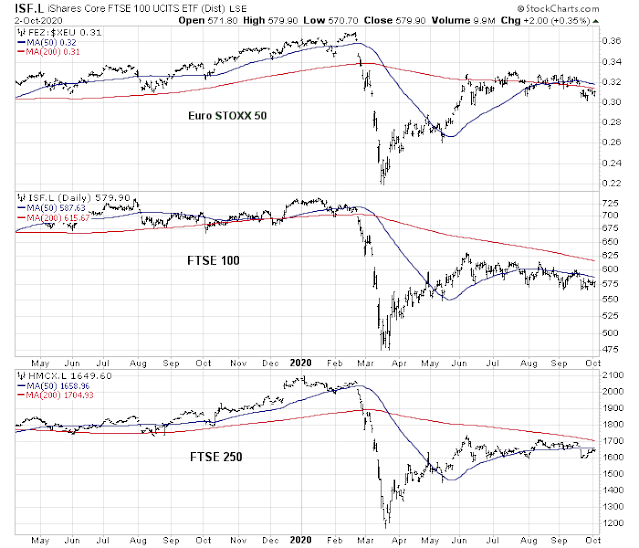

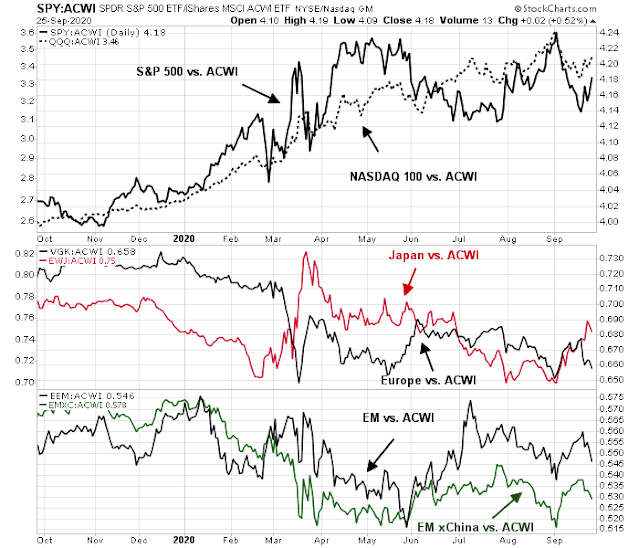

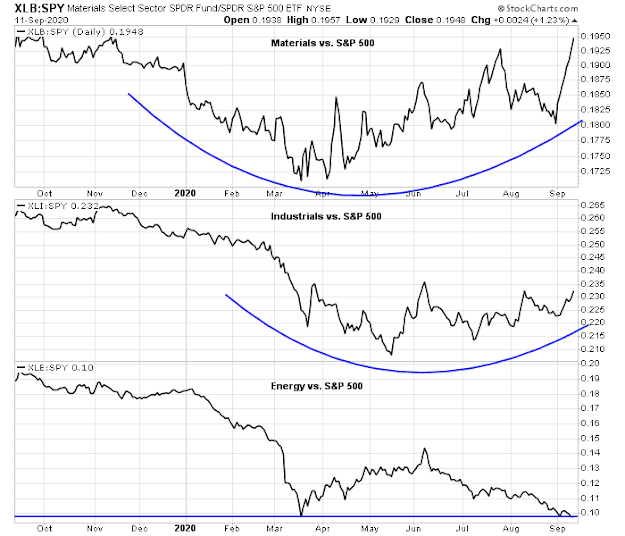

History doesn’t repeat, but rhymes. Undoubtedly there will be some bumps along the way as political regimes change in Washington over the next 10 years, but investors can use the same Abenomics template and should expect similar mixed results in the US economic outlook over the next decade.

Investment implications

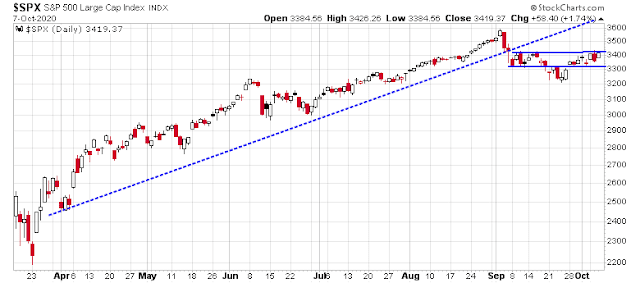

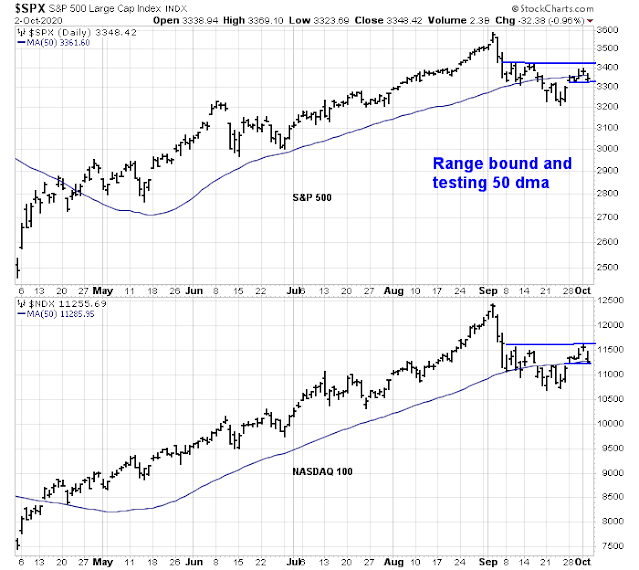

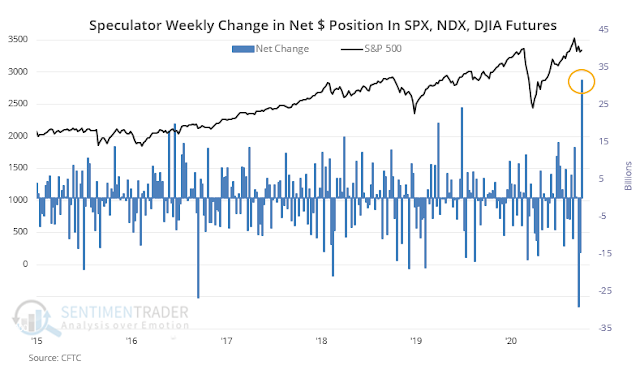

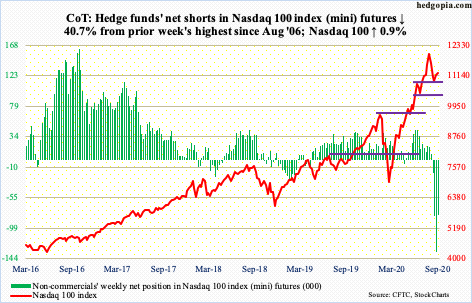

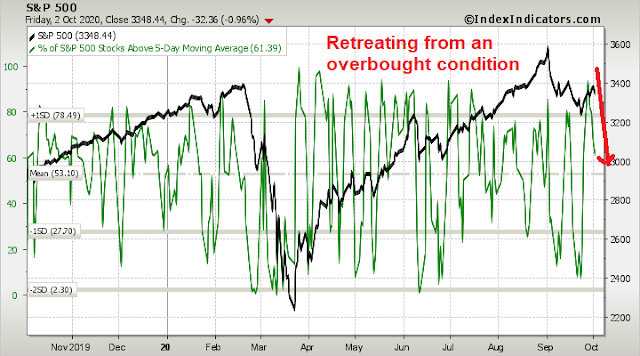

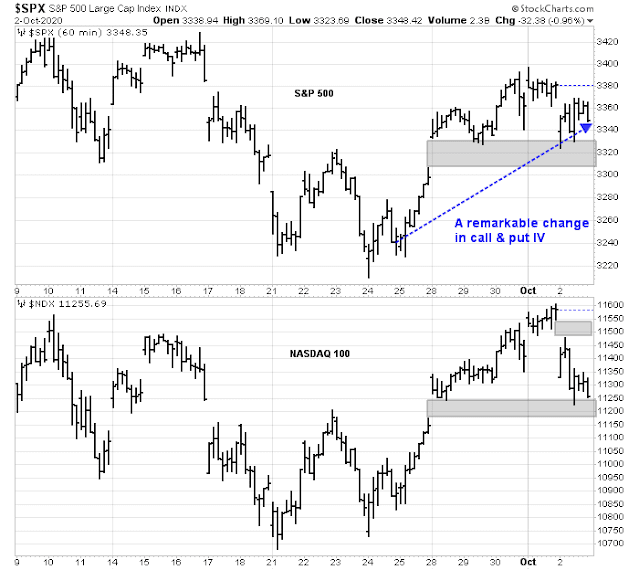

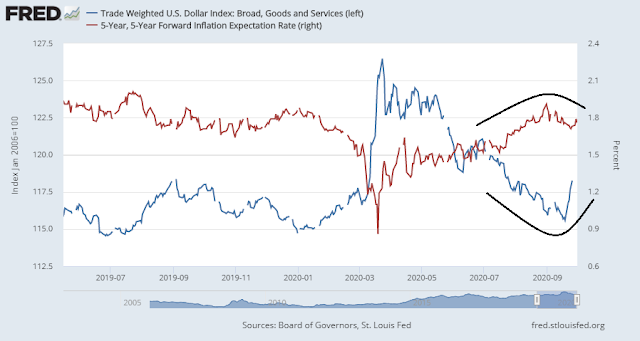

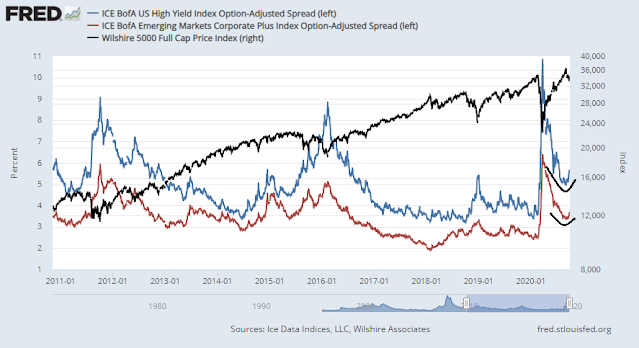

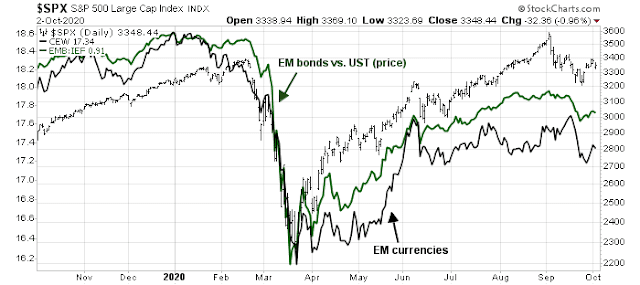

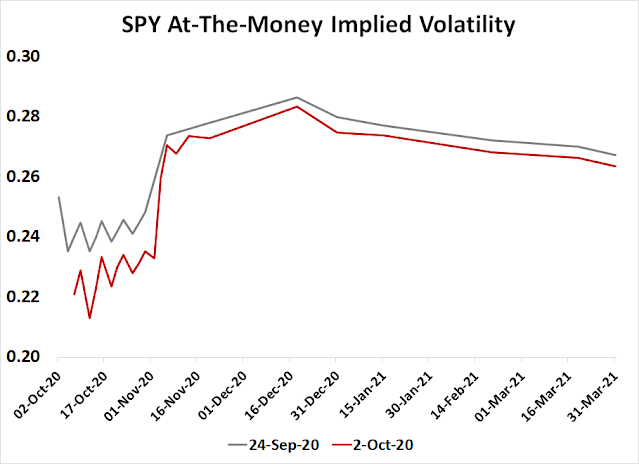

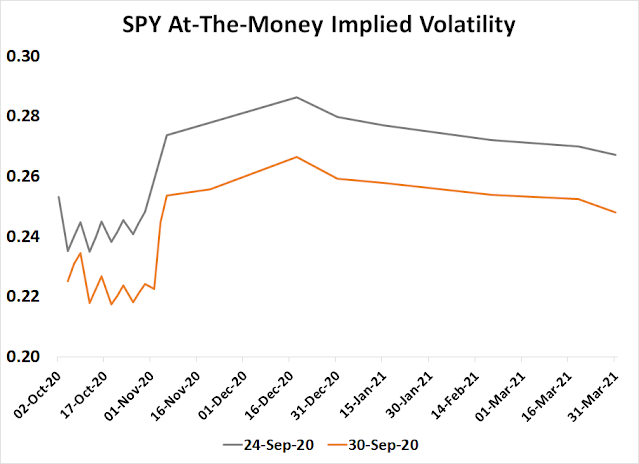

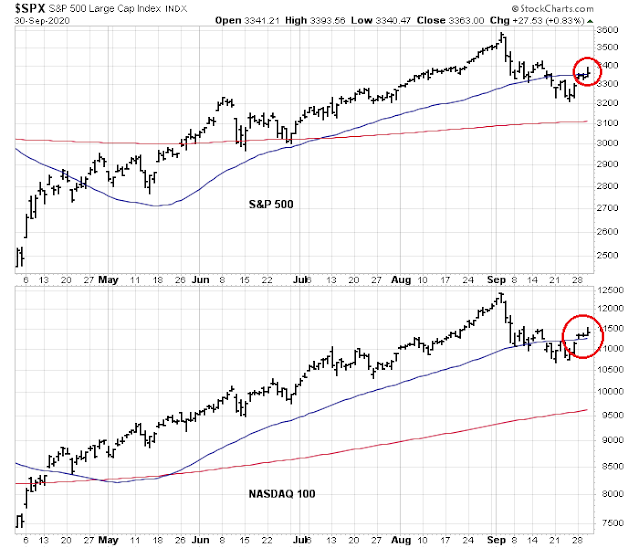

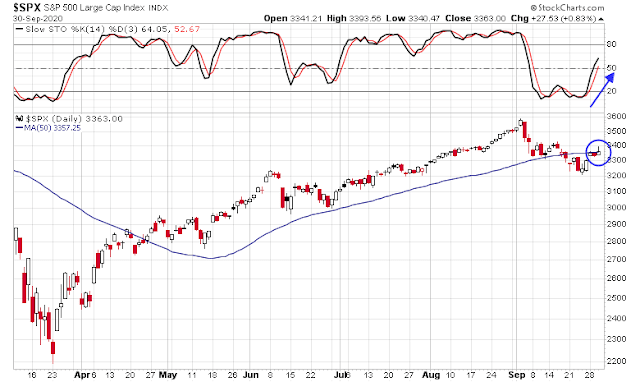

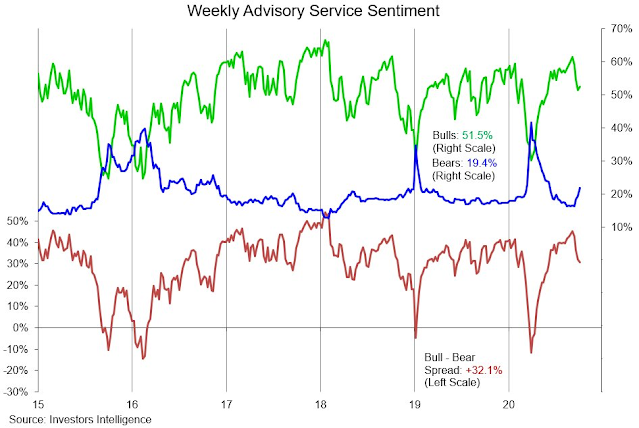

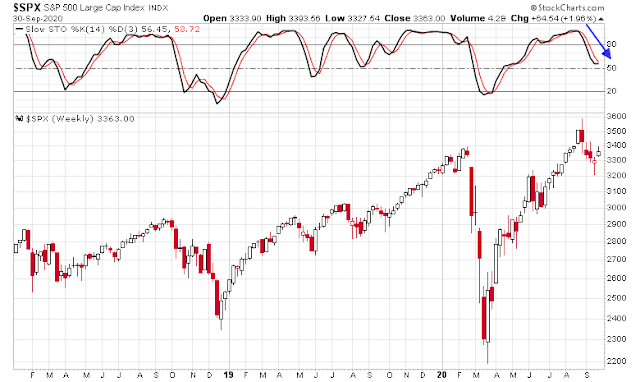

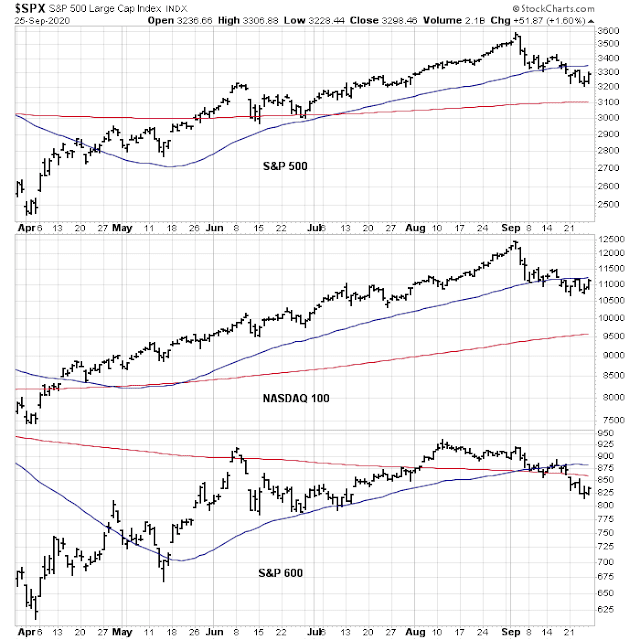

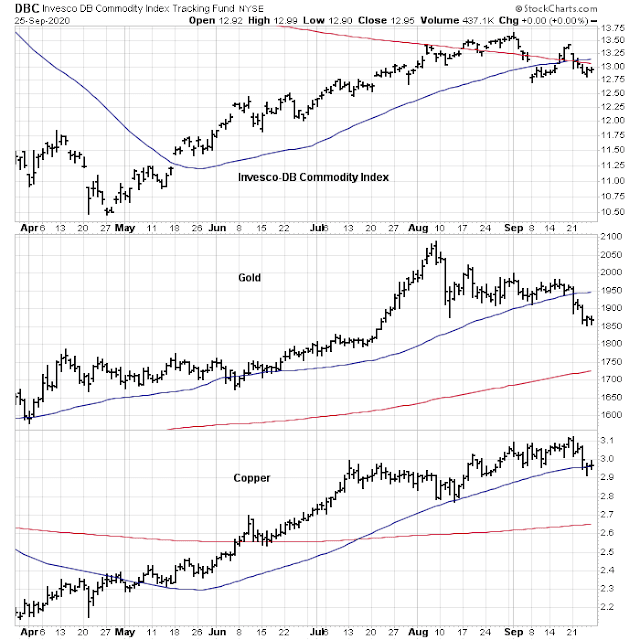

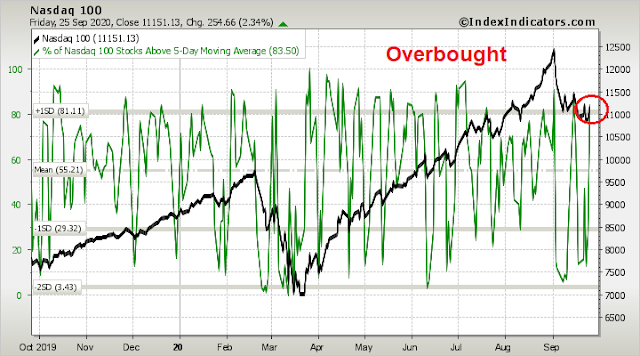

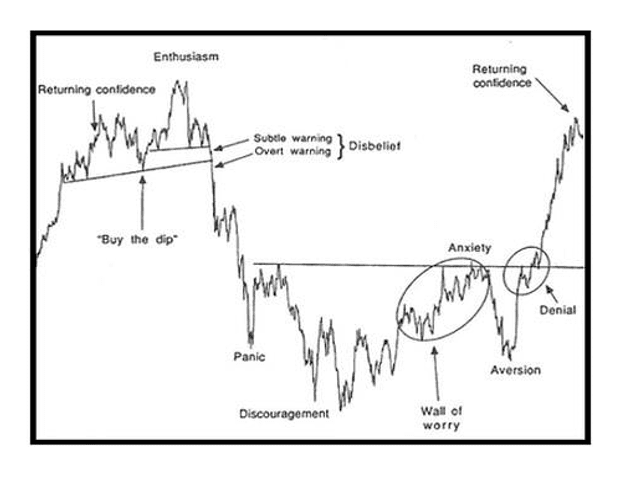

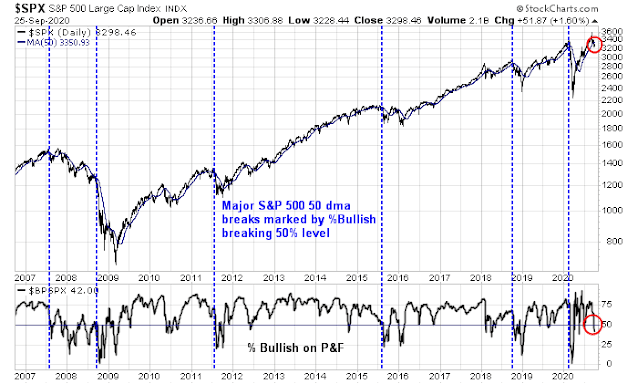

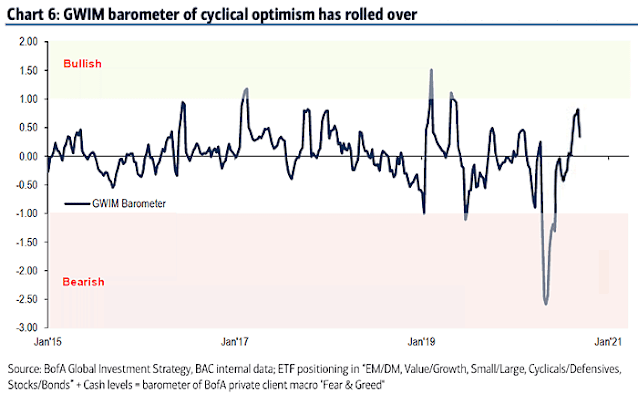

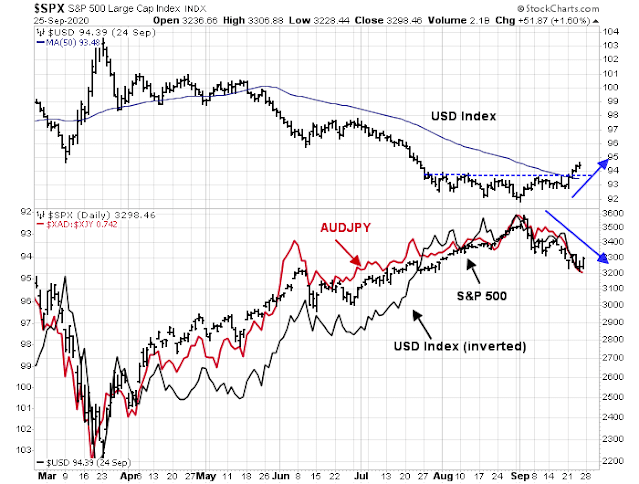

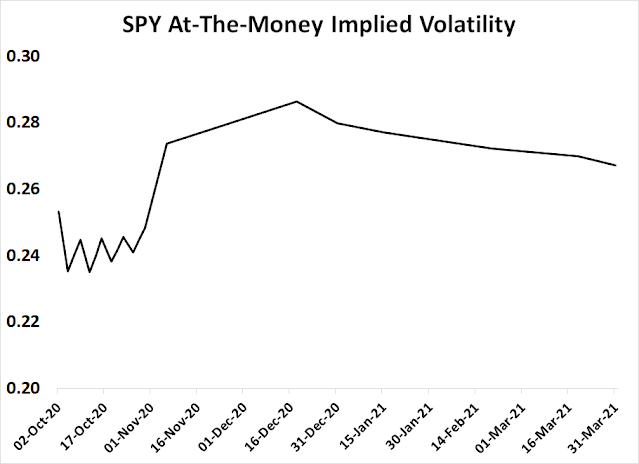

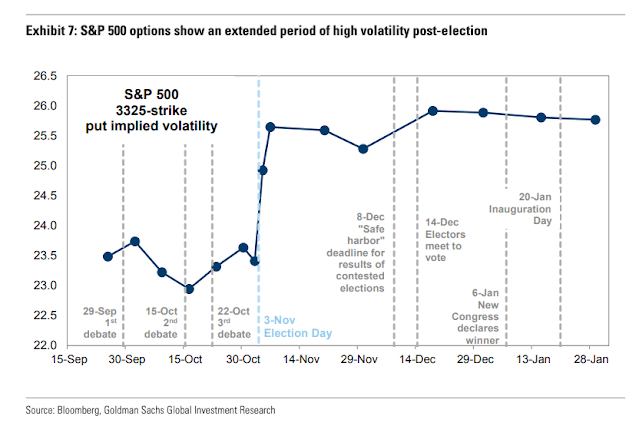

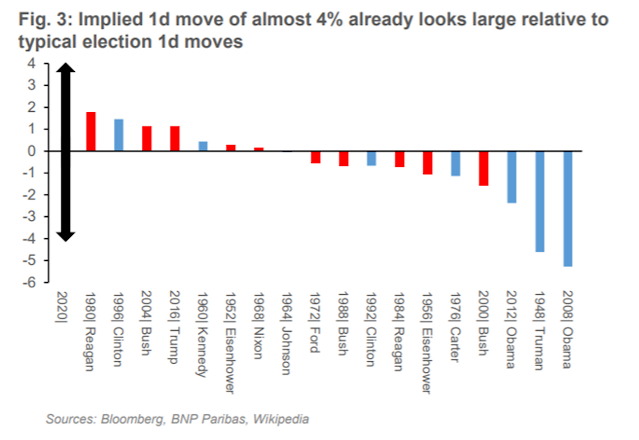

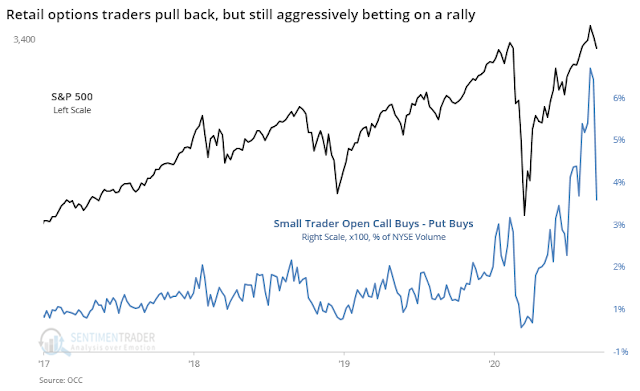

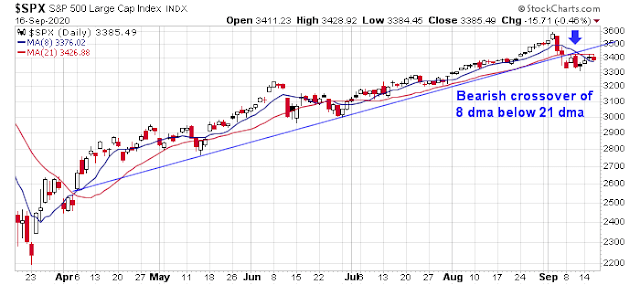

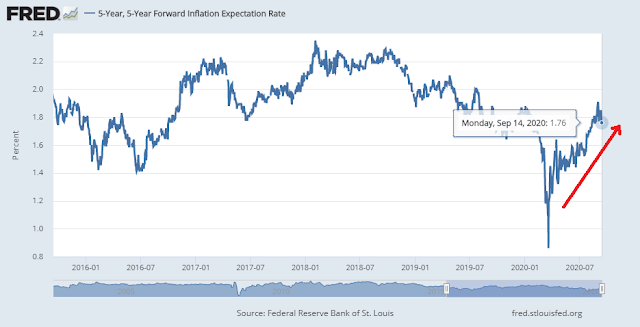

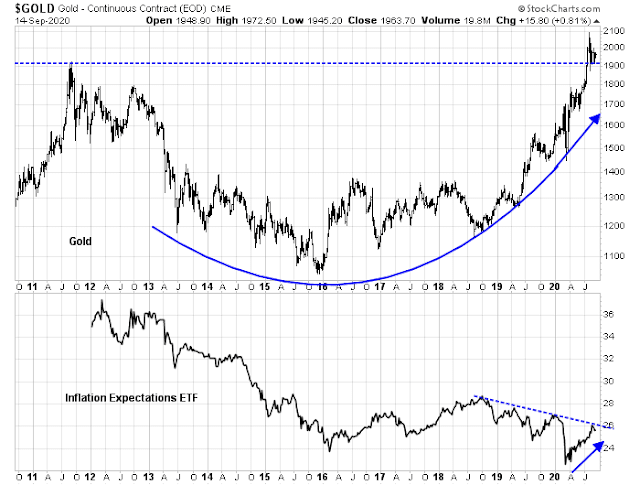

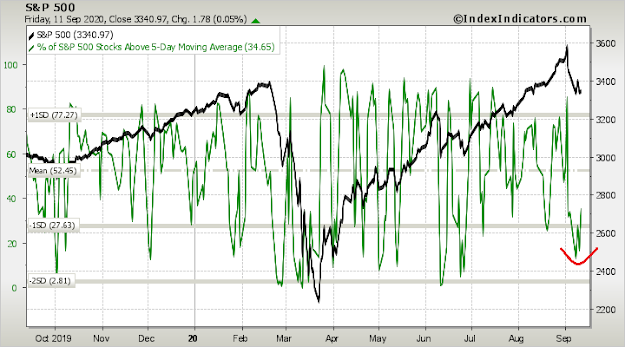

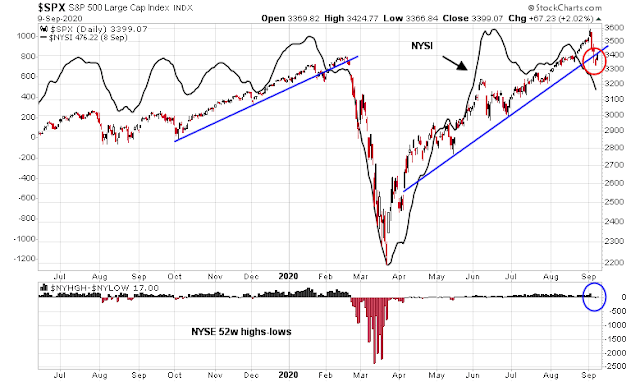

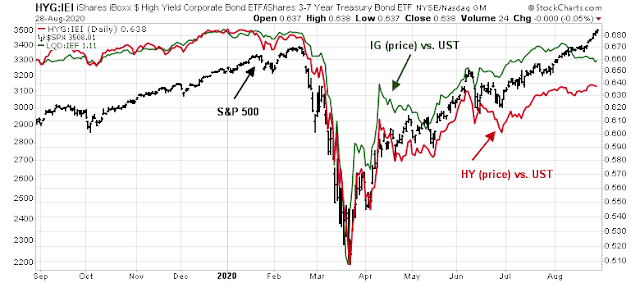

What does all this mean for investors? Over the next 6-12 months, the key variables are the election, the path of fiscal policy, and how the Fed reacts to rising bond yields. Inflation expectations, as measured by the 5×5 forward bond yield, had been rising steadily and peaked at 1.91% last week before retreating. This put upward pressure on the 10-year Treasury yield.

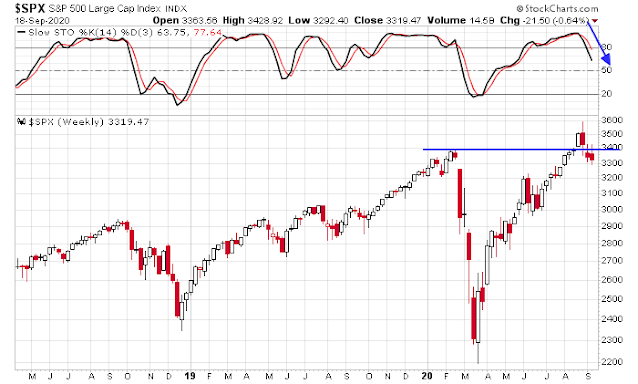

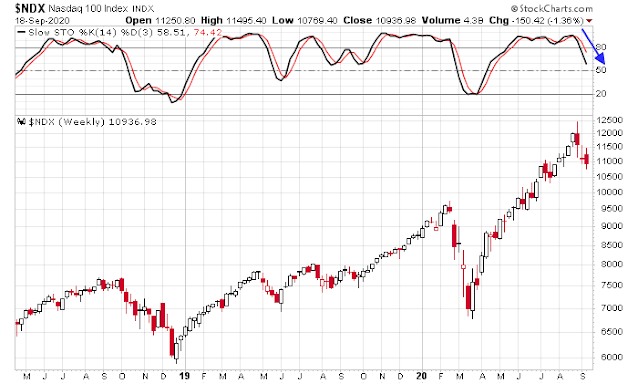

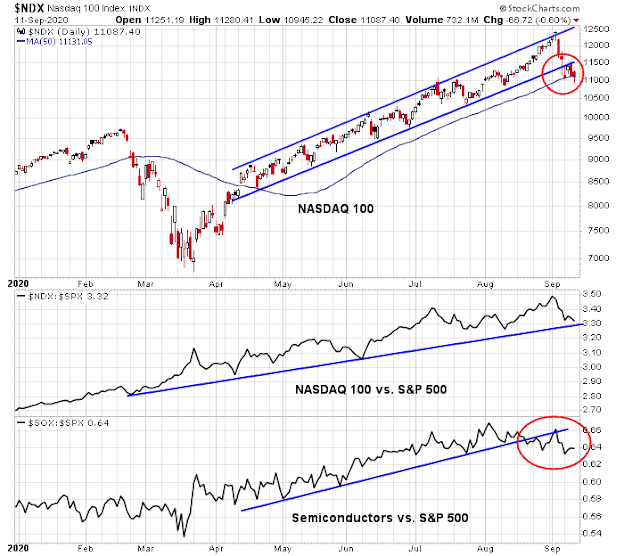

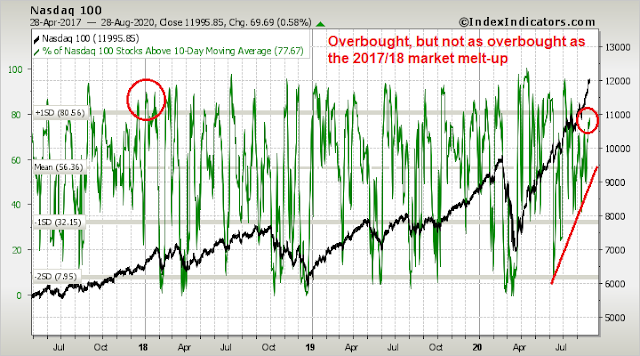

At some point, higher Treasury yields will threaten the fragile economic recovery, and it will also put downward pressure on stock prices. A recent Bloomberg article, “Treasury Yields Will Become A head For Stocks Around 1%”, tells the story. Higher rates will put downward pressure on equity prices.

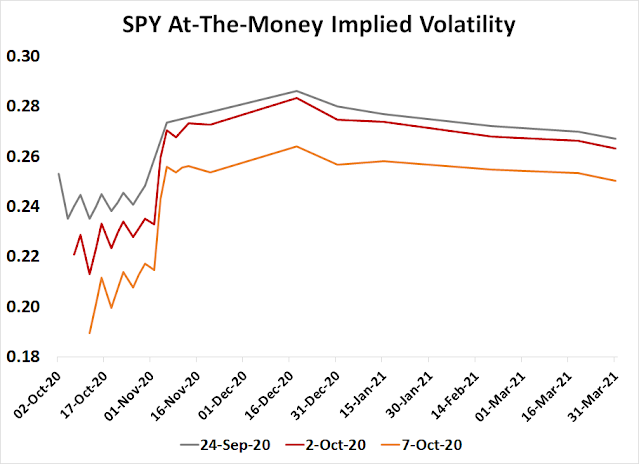

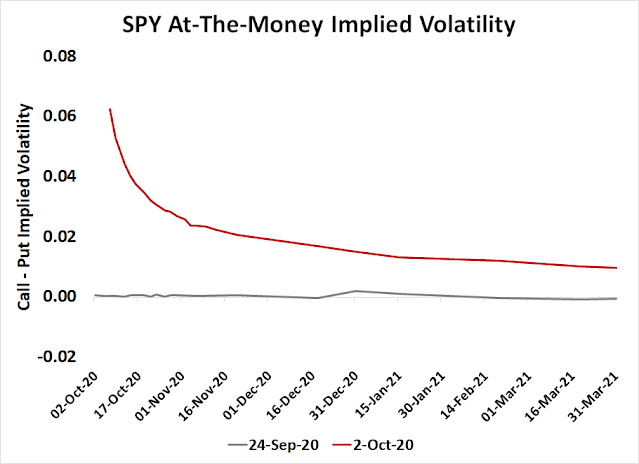

How far will the Fed allow yields to rise? Can it act to hold down yields and maintain the credibility of an average 2% inflation target? Richard Clarida rejected the notion of yield curve control (YCC) in his recent speech, but left the door open for further action in the future.

Most of my colleagues judged that yield caps and targets were not warranted in the current environment but should remain an option that the Committee could reassess in the future if circumstances changed markedly

The Fed is engaged in a tight-wire act with its YCC tool. If it doesn’t suppress rates, it risks snuffing the recovery and stock prices. Suppress rates too much, and it will devastate the banking system by compressing interest rate margins, raise inflationary expectations and run the risk of them becoming unanchored beyond the 2% targeted level. Should it have to resort to YCC, the Fed will begin with jawboning, or forward guidance, before actually intervening in the bond market. Sometime the threat of action is more powerful the actual action itself.

For investors, this means returns in Treasury market are asymmetric. The Fed will allow yields to fall as the market dictates. Fixed income investors should expect returns to be reasonable. There will not be significant downside risk in bond prices. On the other hand, the path of equity prices will be more dependent on more variables: how the world controls the pandemic, the path of fiscal policy, and the evolution of earnings expectations.

In conclusion, the Fed’s policy review raises more questions than answers. The Fed has a limited ability to boost the economy, but it’s known that it has the power kill it. This review has softened the “kill the economy because it’s overheating” policy, but there are many questions about the mechanisms for boosting growth. I expect there will be short-term hiccups between now and the Presidential Inauguration in January, but expect some form of Abenomics like policy over the next decade. The results will be uneven, and will depend largely on the path of fiscal policy, rather than monetary policy.