How badly has the pandemic affected the global economy? The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has some answers in a recent report. It expects global human development to decline for the first time this year, and EM economies will bear the brunt of the impact. The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that up to half of global workers could lose their jobs.

New UNDP estimates Global human development – as a combined measure of the world’s education, health and living standards – is on course to decline this year for the first time since the concept was developed in 1990. The decline is expected across the majority of countries – rich and poor – in every region.

- Global per capita income is expected to fall four percent. The World Bank has warned that the virus could push between 40 and 60 million into extreme poverty this year, with sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia hardest hit.

- The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that half of working people could lose their jobs within the next few months, and the virus could cost the global economy US$10 trillion.

- The World Food Programme says 265 million people will face crisis levels of hunger unless direct action is taken.

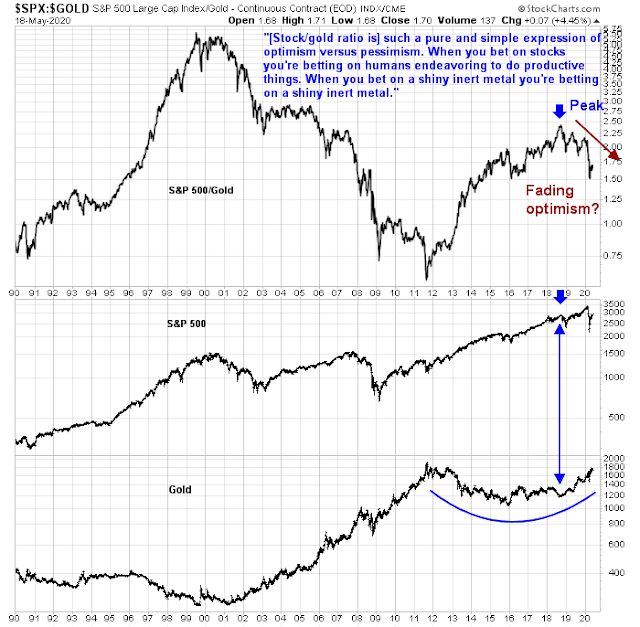

While the human development is falling this year, the market’s perceived decline of confidence did not begin with the COVID-19 pandemic. Last week, I highlighted a comment by Joe Wiesenthal at Bloomberg when he focused on the stock/gold ratio as a barometer of optimism and pessimism (see Checking the small business economic barometer). I would go further to characterize the ratio as a barometer of investment confidence in human ingenuity.

It’s such a pure and simple expression of optimism versus pessimism. When you bet on stocks you’re betting on humans endeavoring to do productive things. When you bet on a shiny inert metal you’re betting on a shiny inert metal.

The chart of the stock/gold ratio surprisingly revealed that it peaked in the summer of 2018 and it has been falling ever since. Since that 2018 peak, both stock and gold prices have climbed, but gold has outpaced stocks. The decline in the stock/gold ratio is worrisome for long-term equity investors.

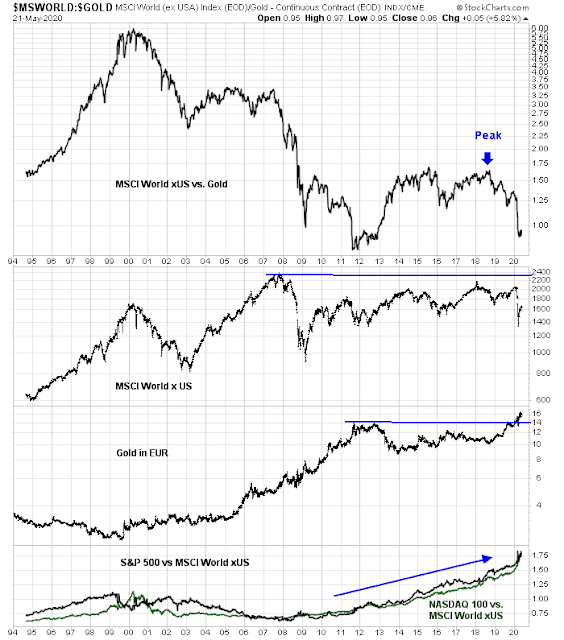

The stock/gold ratio outside the US, as represented by the MSCI World xUS Index, looks even worse. The MSCI World xUS Index never recovered its pre-GFC peak. Gold, as priced in euros, has reached all-time highs. The post-GFC equity market recovery is entirely attributable to the outperformance in the US.

What is the market telling us about optimism and pessimism, and global investment confidence?

I conclude that the outlook for equities faces a number of long-term headwinds, namely de-globalization, rising protectionism, and a difficult growth outlook. Gold represents an insurance policy against falling investment confidence. Investors should re-evaluate their portfolio allocation policy in light of these factors affecting asset returns over the next decade.

America’s sugar high

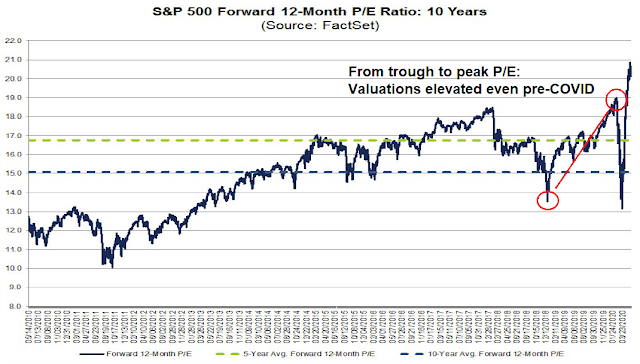

Arguably, the S&P 500/gold peak in 2018 is attributable to the wearing off of the sugar high of the corporate tax cuts enacted in 2017. The history of forward 12-month EPS tells the story. Earnings took a one-time jump in the wake of the tax cuts and rose steadily until late 2018. Since then, estimate growth has been mostly flat until the recent pandemic shock.

We can see the valuation effects of the advance off the Christmas Eve bottom in 2018. The forward P/E ratio rose steadily, until it peaked at 19 just before the COVID-19 crisis.

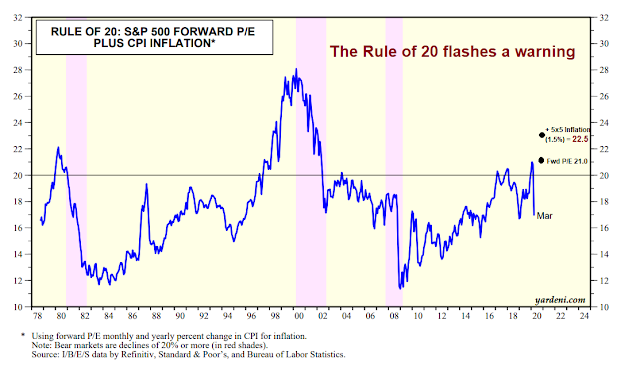

Elevated valuations have sparked Rule of 20 warnings, which flashes a sell whenever the sum of the forward P/E ratio and inflation rate exceeds 20. The market was already overvalued based on the Rule of 20 even before the onset of the pandemic. Stock prices duly retreated as the COVID-19 crisis evolved, but the latest recovery is flashing another Rule of 20 sell signal.

Is there any wonder why the stock/gold ratio is turning down? Earnings had been stagnant, but stock prices were rising. It is therefore no surprise that the market began to discount this negative divergence and gold price outperformed in response.

Depression in Europe and Japan

Outside the US, economic depressions are evident. Jerome Powell was asked about the possibility of a second great depression in his recent 60 Minutes interview.

PELLEY: 25% is the estimated height of unemployment during the Great Depression. Do you think history will look back on this time and call this the Second Great Depression?

POWELL: No, I don’t. I don’t think that’s a likely outcome at all. There’re some very fundamental differences. The first is that the cause here– we had a very healthy economy two months ago. And this is an outside event, it is a natural disaster, in effect. And that’s one big difference. In the ’20s when the Depression, well, when the crash happened and all that, the financial system really failed. Here, our financial system is strong has been able to withstand this. And we spent ten years strengthening it after the last crisis. So that’s a big difference. In addition, the last thing I’ll say is that the government response in the ’30s, the central banks were trying to raise interest rates to keep us on the gold standard all around the world. Exactly the opposite of what needed to be done.

In this case, you have governments around the world and central banks around the world responding with great force and very quickly. And staying at it. So I think all of those things point to what will be — it’s going to be a very sharp downturn. It should be a much shorter downturn than you would associate with the 1930s.

There are a few points to unpack in Powell’s response. First, he was correct that fiscal and monetary authorities were overly tight in the wake of the 1929 Crash and tightened policy, all in the name of the gold standard. It was therefore unsurprising to see the stock/gold ratio plunge in response during the 1930’s.

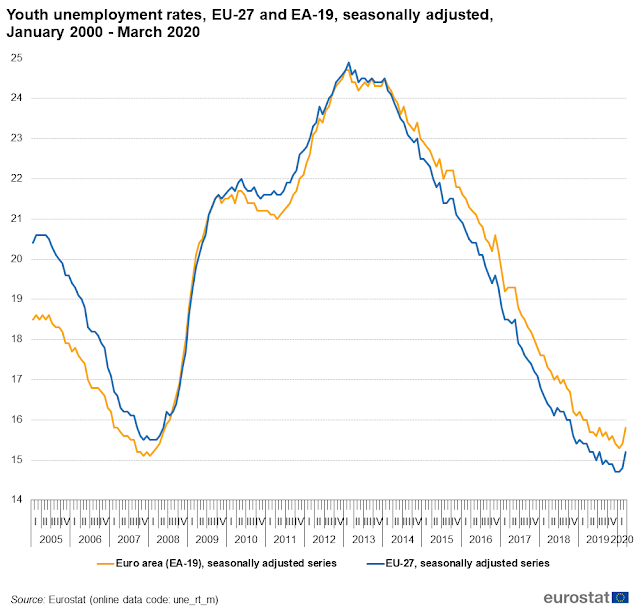

He was incorrect that the fiscal and monetary responses are always sufficient to prevent another depression. While the US has not experienced a depression since the Dirty Thirties, parts of Europe have been in a depression in the last decade. The EU and eurozone unemployment rates rose steadily in the wake of the GFC. While they have recovered to their pre-crisis lows, absolute levels remain elevated. In particular, peripheral country unemployment rates are still horrendous. The adjustment in Greece was borne mainly by an internal devaluation of wages.

In addition, youth unemployment in Europe remains in double digits, and it is especially high in peripheral countries. This is creating a lost generation, which has negative effects on productivity and has the potential to create social and political turmoil.

The ECB’s initial LTRO response in 2011 did take away the tail-risk of the breakup of the eurozone, and put a floor on the price of risk assets. ECB policies were designed to buy time for member states to reform and restructure their economies. At the time, Mario Draghi referred to labor market reforms to create greater economic dynamism, and to break the perception of lifetime security for the older generation, so that youth unemployment could decline. But reforms were either too slow or not forthcoming. The ECB did what it could to support markets and hold the eurozone together, but its policy of negative interest rates was a bridge too far. The negative interest rate policy has devastated the European banking sector.

While recessions are well-defined, there is no standard definition of a depression. That said, it is difficult to characterize peripheral Europe as being anything but a depression since 2011.

Similarly, Japan’s Nikkei Index has gone nowhere for decades despite fiscal and monetary support. Gold in JPY has broken out to fresh all-time highs.

Trade and globalization in retreat

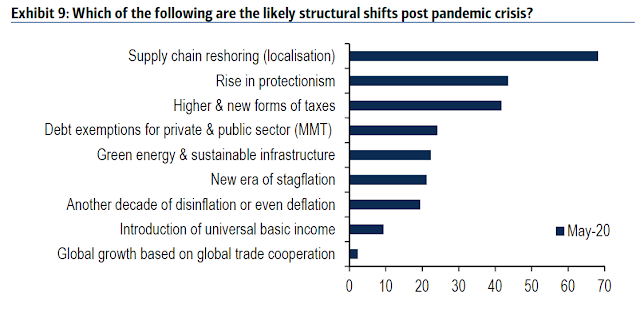

Looking ahead, what’s the outlook for the next decade and beyond? The crystal ball is a little hazy, but the latest BAML Global Fund Manager Survey provided some clues of investor expectations.

The biggest theme is rising protectionism and de-globalization. The Economist devoted an entire issue on the topic.

Trade will suffer as countries abandon the idea that firms and goods are treated equally regardless of where they come from. Governments and central banks are asking taxpayers to underwrite national firms through their stimulus packages, creating a huge and ongoing incentive to favour them. And the push to bring supply chains back home in the name of resilience is accelerating. On May 12th Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, told the nation that a new era of economic self-reliance has begun. Japan’s covid-19 stimulus includes subsidies for firms that repatriate factories; European Union officials talk of “strategic autonomy” and are creating a fund to buy stakes in firms. America is urging Intel to build plants at home. Digital trade is thriving but its scale is still modest. The sales abroad of Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Microsoft are equivalent to just 1.3% of world exports.

The flow of capital is also suffering, as long-term investment sinks. Chinese venture-capital investment in America dropped to $400m in the first quarter of this year, 60% below its level two years ago. Multinational firms may cut their cross-border investment by a third this year. America has just instructed its main federal pension fund to stop buying Chinese shares, and so far this year countries representing 59% of world gdp have tightened their rules on foreign investment. As governments try to pay down their new debts by taxing firms and investors, some countries may be tempted to further restrict the flow of capital across borders.

FT Alphaville outlined several defenses of globalization, starting with theory of comparative advantage. The defense also offers a glimpse of what might happen if globalization were to retreat and trade barriers go up around the world.

Economics offers more rational reasons why it doesn’t make sense to source everything close to your doorstep. Take, for instance, nineteenth-century economist David Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage. If England can produce cloth far more efficiently than Portugal due to mechanisation, and Portugal wine far easier due to its geography, is it not in the interest of both nations to focus on specialisms in which they can thrive? (Though this argument became somewhat overdone in the era of hyper-globalisation.)

Although the pandemic has exposed the vulnerabilities of the low-cost and just-in-time model of global supply chains, unwinding those relationships will raise costs, and compress margins.

Clearly transportation is easier and less vulnerable if suppliers are close by. While this could be overcome by building up stockpiles of parts, this would add additional costs or be impossible in the case of perishable goods.

Just-in-time production has become emblematic of the pre-Covid 19 economy. Supply chains had become so efficient that goods often went straight from the delivery bay and on to shelves. That may have to be reassessed if we make a choice that we want the supply of some goods to be more robust.

De-globalization would reduce also innovation.

Without open borders and global networks, many innovations would cease to exist. That – say Anna Stellinger, Ingrid Berglund and Henrik Isakson of the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise – includes drugs and other medical goods

In the end, the biggest question is what price the inhabitants of the developed market are willing to pay for the supply security.

At its core, the debate about global value chains right now is not about growth. It is about how society provides goods deemed essential in times of crisis…

In times marked by fear and protectionism, there are risks to relying on borders remaining open and global value chains delivering. But it is in the best interests of us all that they do.

Current consensus opinion seems to be tilted towards greater supply security. It won’t matter who wins the election in November. The US view on China from both sides of the political aisle is becoming increasingly antagonistic. In addition, the COVID-19 crisis has laid bare the vulnerabilities of global supply lines, especially in pharmaceuticals and medical equipment. At a minimum, expect greater pressure to onshore more production in all industries in 2021.

In the short run, China is falling far short of the targeted purchase of US goods under the Phase One trade agreement, largely owing to a collapse in demand as the Chinese economy tanked. This has the potential to create more trade friction and spook the markets over the next few months.

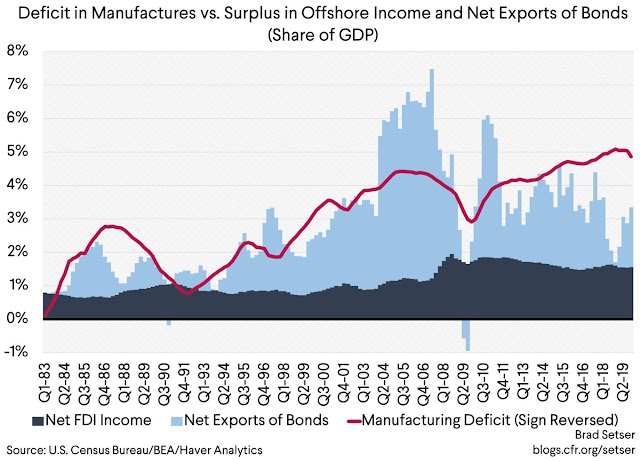

From a practical point of view, Brad Setser at the Council on Foreign Relations distilled the American experience with globalization over the last 40 year.

- A rising trade deficit in manufacturing.

- Growing offshore profits (mostly in tax havens).

- And large exports of bonds to make the sums balance.

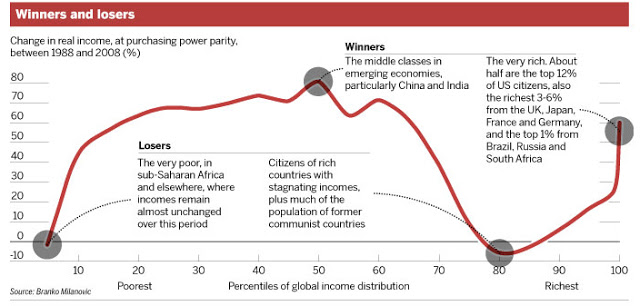

As shown by Setser’s analysis and by Branko Milanovic’s famous elephant graph, the benefits of globalization have accrued to the EM rising middle class, developed market manufacturers that can offshore production, and producers of intellectual capital that can offshore production and dam the profits in offshore tax havens. The main losers have been the developed market middle class.

Estimating the COVID-19 fallout

Another long-term trend to consider is the generational effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has the potential to create a lost generation and political turmoil. Deutsche Bank analyzed what happened during the Spanish Flu and other pandemics and found the following:

- Studies have found that the cohort born around the time of the Spanish flu in 1919 had worse educational outcomes throughout their lives.

- Pandemics have long been associated with conspiracy theories, and in turn have been connected with lower levels of social trust. For example, today’s conspiracy theory has been about 5G but there were suggestions that Spanish flu was spread by Germans of some form of biological weapon at the end of WWI.

- Meanwhile economic downturns have their own lasting legacies. For young graduates who join the workforce in a recession, it can take up to a decade before their earnings recover to where they would have been. And prior recessions suggest it could take years before employment returns to its pre-Covid levels.

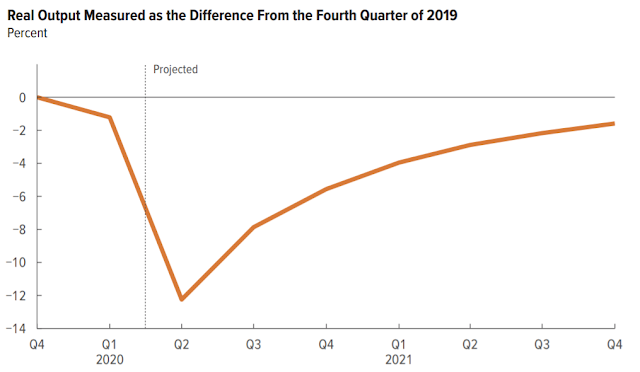

On the last point, the economy is likely to take a considerable time to recover. The latest Congressional Budget Office forecast shows that GDP will still be 2% below the Q4 2019 peak at the end of 2021.

A University of Cambridge study projects a five year loss of between 0.65% to 16.3% of global GDP, with a mid-range forecast of 5.3% to global GDP.

The GDP@Risk over the next five years from the coronavirus pandemic could range from an optimistic loss of $3.3 trillion (0.65 per cent of five-year GDP) under a rapid recovery scenario to $82.4 trillion (16.3 per cent) in an economic depression scenario, says the Centre for Risk Studies at the University of Cambridge Judge Business School.

Under the current mid-range consensus of economists, the GDP@Risk calculation would be $26.8 trillion or 5.3 per cent of five-year GDP, says a “COVID-19 and business risk” presentation prepared by the Centre for Risk Studies.

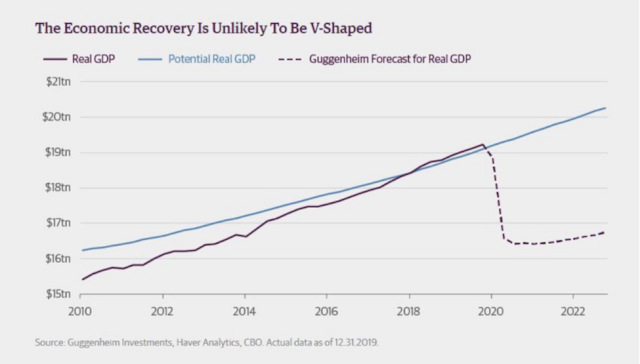

It took about 10 years for US GDP to return to potential after the GFC. How long will it take post-COVID?

The slowness of the recovery will have consequences. Surges in unemployment have been correlated with a spike in bankruptcies. So far, the number of Chapter 11 filings has been limited. While the Fed has offered unprecedented levels of support for the credit markets, it cannot supply solvency, or equity, if a firm were to fail. Will this cycle be any different?

Gold as confidence insurance

The combination of all these factors point to subpar equity returns over the next decade. Does that mean you should be buying gold to hedge against a decline in stock/gold ratio?

Gold can have a role in portfolios, but I believe that investors should buy gold for the right reasons. Here are some wrong ways to play gold and gold related vehicles.

Forget gold as an inflation hedge. The chart below shows that gold staged an upside breakout in 2018 out of a multi-year base that stretches back to 2013. The price is now approaching a resistance zone, as defined by its all-time high. By contrast, the bond market inflationary expectation ETF (RINF) has been in a downtrend since late 2018. While inflationary expectations have begun to tick up, RINF is just approaching and testing a resistance zone.

During the current deflationary period marked by a collapse in demand, the world would be lucky to see signs of inflation, which would be a signal of renewed growth. If you want to bet on inflation, buy equities, as they would perform well in periods of moderate inflation. As well, companies with strong pricing power that can pass through price increases would perform well in low but rising inflation environment. One shortcut might be the shares of Berkshire Hathaway. Warren Buffett has assembled a portfolio of companies with strong competitive positions, or moats, that should have better pricing power should inflation and growth return.

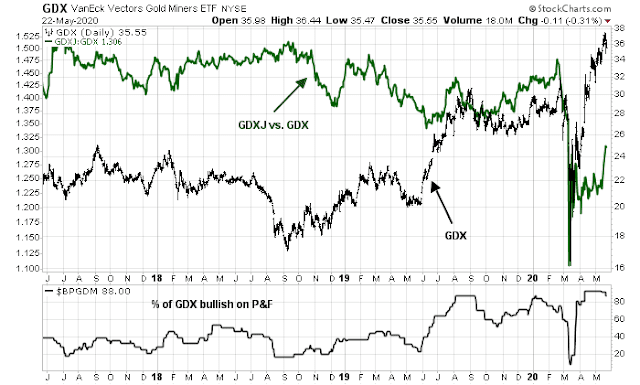

Even for more aggressive investors who are seeking greater leverage in the gold price, I would advise against buying gold stocks instead of gold. Despite the commonly held belief that the stocks provide better leverage to the gold price, gold stocks have dramatically lagged gold prices in the last decade

Here is why. Conceptually, a gold mining company can be thought of as a call option on the price of gold, with the strike price set at the cost of production, combined with the expected amount of gold the company can mine in each year for the term of the mine life, or mine lives. The historical record has shown that as old mines become exhausted, companies have replaced production with new mines with higher production costs. In effect, this creates the effect of changing the strike price of an option upwards, which reduces the value of the option. Unless the gold mining industry can find new lower cost mines, the shares of gold mining companies are likely to continue to lag gold prices in the future.

In the short run, here is another reason to avoid gold stocks. Senior golds, as represented by GDX, have become overbought. The percentage of stocks in the ETF is over 90%. At the same time, the performance of gold golds (GDXJ) are lagging GDX, which is a negative divergence.

In conclusion, the outlook for equities faces a number of long-term headwinds, namely de-globalization, rising protectionism, and a difficult growth outlook. Gold represents an insurance policy against falling investment confidence. Investors should re-evaluate their portfolio allocation policy in light of these factors affecting asset returns over the next decade.

https://www.marketwatch.com/story/were-in-a-new-paradigm-for-stocks-this-analyst-argues-get-ready-for-permanently-higher-valuations-2020-05-19?siteid=yhoof2&yptr=yahoo

Another venerable analyst Nick Colas echoes a similar sentiment as Liz Ann Saunders.

That said, I agree with Cam, despite what Liz Ann Saunders and Nick Colas are suggesting (that stocks will continue to power higher), the Corona Virus is a new paradigm and without durable solutions, we could be in an extended period of economic malaise, bordering on depression. Cash will become king and company after company will go under (todays casualty is Hertz).

All said, we are in a very early phase of this epidemic. Deglobalization will do rest of the damage.

At a personal level, I went to buy an iPhone 11 last night. First delivery is not till next Wednesday. I phone SE delivery is not till 4th June. Ever wondered what happens to prices of Iphones?

To Cam’s suggestion of buying wide moat companies, don’t FAANG stocks have wide moats? The valuations of these companies do reflect what Nick Colas is suggesting. That said, one year later, it may be a different story and these companies may get cheaper as depression like conditions take hold.

Here is the link to Liz Ann’s missive;

https://www.schwab.com/resource-center/insights/content/every-picture-tells-story-chartbook-look-economymarket

https://twitter.com/sentimentrader/status/1264154580130189312

Volume spiked in March and is now falling.

SPY’s volume is now -64% below its 3 month average, while the S&P is under its 200 dma

When this happened over the past 20 years, U.S. stocks ALWAYS pulled back over the next 2 months, sometimes *very sharply*

A special offer for my fellow Humble Students.

On this blog, you have been hearing about my momentum factor research. These studies have led to me making some important new discoveries of how the four basic factors (Value, Growth, Small Cap, Low Volatility) can signal precise important market and industry turning points. My clients shifted almost entirely out of equities two business days after the February 18 peak and into bonds for example. We watched in safety as markets plunged. An important bottom turning point was signaled two business days before the March 23 low. How good is that!

This new factor research also shows the ongoing strengths and weaknesses of industry sectors by revealing the trends of their individual internal factor dynamics.

I’d love to show anyone interested in this with a one-on-one web meeting. Just email me at ken.macneal@tacticalfactorresearch.com and we can set a convenient time.

As I always say, “We are in this together”

What is your model saying right now?

Great Ken, I will email you. Always love your opinions

https://us.matthewsasia.com/resources/docs/pdf/Sinology/051820-Sinology.pdf

‘China’s economy looks to be well on its way to recovering from the coronavirus-imposed lockdown. A return to normal may not happen until next year, but consumer spending, manufacturing and investment appear to be all bouncing back strongly. This raises the perennial question, “Can we trust China’s macro numbers?” A look at sales data from multi-nationals (MNCs) doing business there suggests that China’s retail sales growth rates are realistic.’

After the initial coronavirus-imposed lockdown, I’ve heard that factories lights and machines were turned on to use electricity. There were zero workers in the factories. The resulted use will be registered with their electric companies. This was/is one way to gauge the level of manufacturing activities in China. No idea if this is real. I do have a bias since China has a perfect record of breaking laws, treaties, contracts etc… and lying. I will take that with a grain of salt.

https://www.sfgate.com/science/article/Sweden-herd-immunity-experiment-backfires-covid-15289437.php

https://www.marketwatch.com/story/call-it-fate-call-it-karma-why-the-coronavirus-is-merely-the-final-kick-into-the-abyss-for-the-us-economy-2020-05-19?siteid=yhoof2&yptr=yahoo

There are a lot of doomsday sayers that are prophesying the end of the good ‘ol USA. I am unsure I buy this idea. Call me whatever, but having traveled to other parts of the world, including China and Taiwan, and many other parts of the world, I just do not buy that a virus spells the death knell for the US of A. Just not buying it, at least not on Memorial day.

Simply does not work like this.

So I have heard of a lot projections. I have heard of a lot of ‘Estimates”. I have heard from lot of “experts”.

I have been hearing this for the last several market cycles.

What is the truth is the question. Does anyone reading this know the truth, what happens in the next one, two, five or ten years?