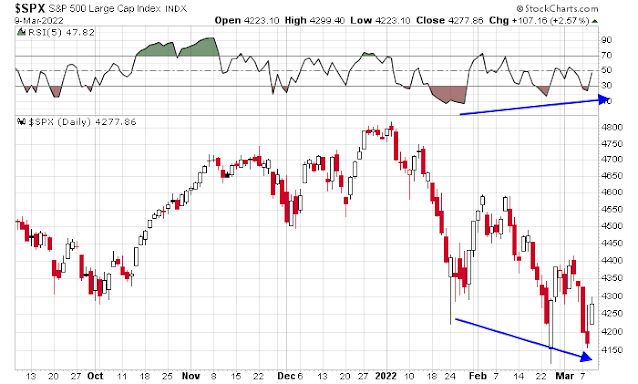

Take a look at this mystery chart. Is that a bullish or bearish pattern? This chart is just the start of my nine reasons to be bearish on risk assets. My analysis is mainly based on real-time pricing signals from the market and relies less on fundamental or macro analysis.

This is a time for investors to be cautious and think more about risk than return. That said, I offer one silver lining in all the dark clouds. There is one (sort of) reason to be bullish.

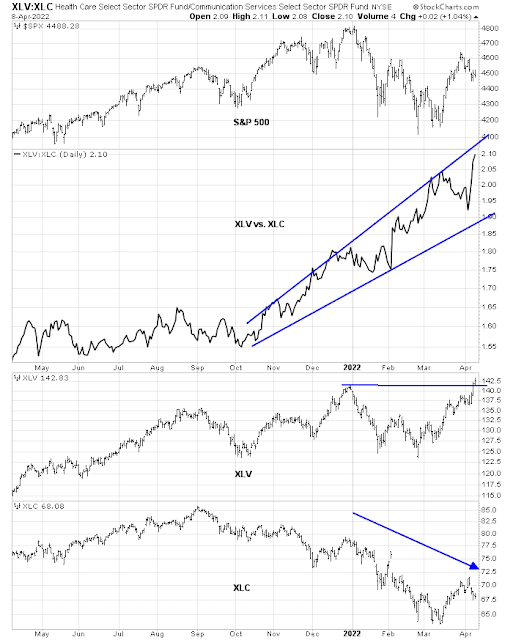

A failed geopolitical risk rally

Sometimes it’s useful to view a chart upside down. The mystery chart is MSCI Poland in USD, which I use as a proxy for geopolitical risk. The Polish market bottomed out in early March as Russia-Ukraine war fears peaked. Unfortunately, the rebound had no legs and began to fade in April. The relative performance of Poland to the Euro STOXX 50 (bottom panel) also shows an ominous pattern of lower lows and lower highs.

The relative performance of major eurozone equity markets to the MSCI All-Country World Index (ACWI) is similarly discouraging. In particular, relative weakness is more evident in core eurozone than the periphery, which is negative for the region’s economic and market outlook.

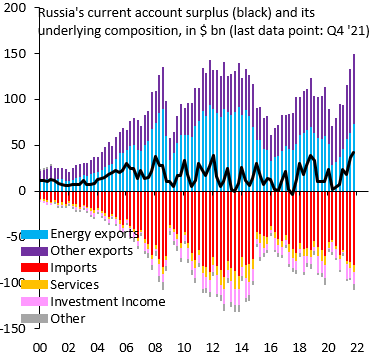

Much of the weakness is attributable to the size of the energy shock that Europe has to endure. The EU’s energy burden as a share of GDP spiked to 9.1%, which is a level not seen since the late 70’s and early 80’s. Across the Atlantic, the effects of higher US energy costs are mild by comparison.

A failed rate hedge

The second reason why I am cautious on the markets is the inability of hedges to work, which is a signal that the plumbing of the markets is broken somewhere. The Rising Rates ETF (EQRR) is supposed to hedge against rising rates. To be sure, yields have risen across the board and EQRR has held its own on an absolute basis. However, the bottom panel shows that the relative performance of EQRR is rolling over, which I interpret as a sign that factor returns are behaving in unexpected ways.

Cyclicals breaking down

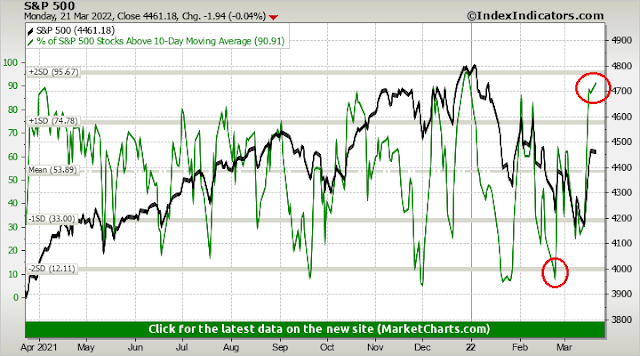

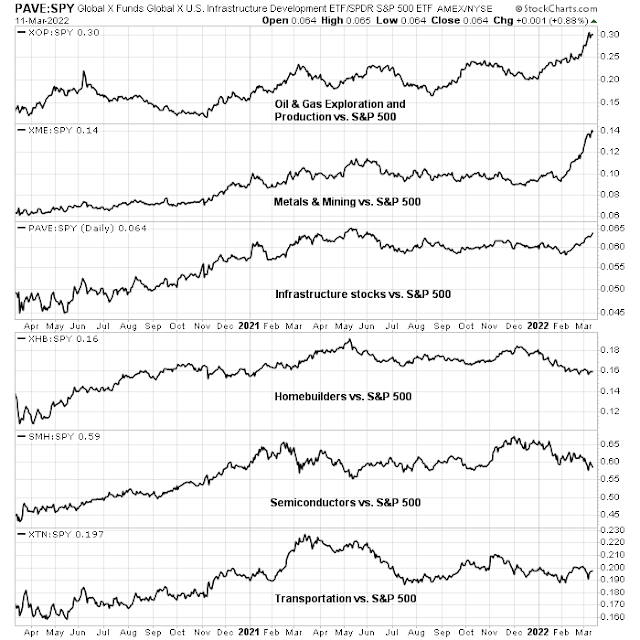

If we look under the hood of the EQRR portfolio, we can see that it has a large weight in financial stocks, followed by resource extraction sectors and other cyclicals. While commodities and resource extraction stocks have performed well, other cyclical industries have been tanking.

This relative performance analysis of cyclical industries tells the story. While infrastructure stocks are holding their own relative to the S&P 500, all of the other industries are either breaking down or in a relative downtrend. This is an unambiguous message from the market that’s screaming “cyclical slowdown”.

The relative performance of homebuilding stocks is indicative of the headwinds faced by cyclical stocks. Historically, the relative performance of this industry has been inversely correlated with mortgage rates. As interest rates rise, this highly cyclical industry faces some tough challenges. As well, the relative weakness in homebuilding has been confirmed by lumber prices.

A Dow Theory sell signal

The poor performance of the Dow Jones Transportation Average is equally worrisome as a sign of cyclical weakness. Not only have the Transports plunged in just a few days, they have also breached a relative support level compared to the Dow Jones Industrials Average.

Mark Hulbert reported that Manuel Blay issued a sell signal on February 22.

According to Manuel Blay, editor of TheDowTheory.com, is that the stock market is punishing U.S. firms that rely on international supply chains. He points out that U.S. companies that are “more local [and] less outsourced” recently have significantly outperformed.

For the record, I note that Blay doesn’t base his market timing advice on the Dow Jones Transportation Average alone. Consistent with his interpretation of the Dow Theory, the oldest market timing system that remains in widespread use today, he instead focuses on both the Dow Transports and the Dow Jones Industrial Average. On that basis, Blay issued a “sell” signal on Feb. 22 of this year.

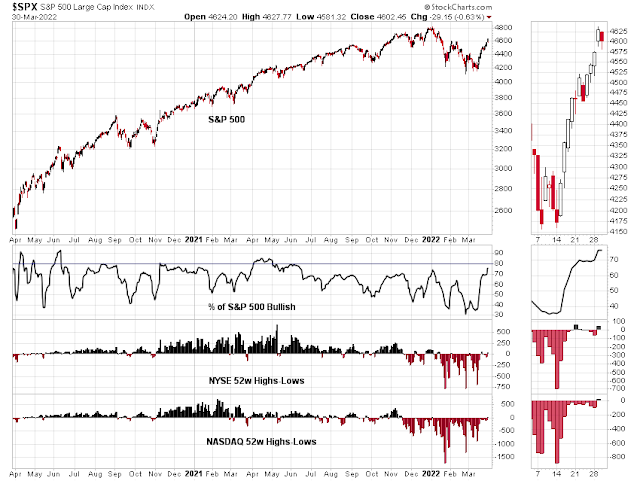

Defensive leadership

On the other hand, defensive sectors are all in relative uptrends.

For the sake of completeness, the relative performance of the major growth sectors is also weak.

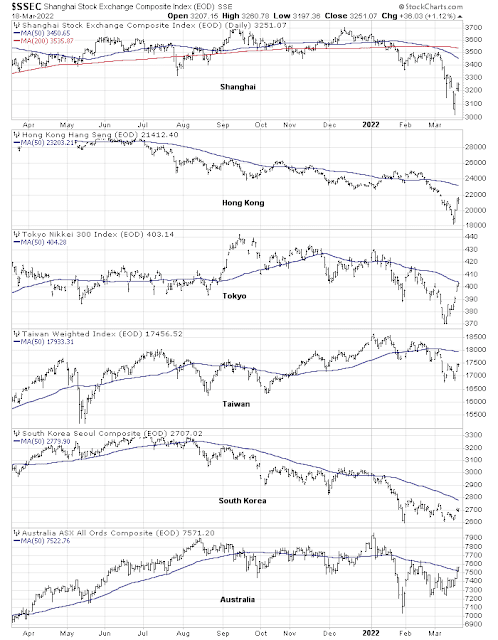

No help from China

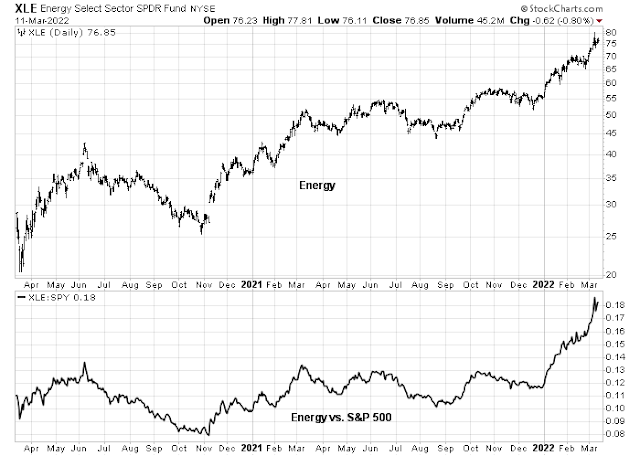

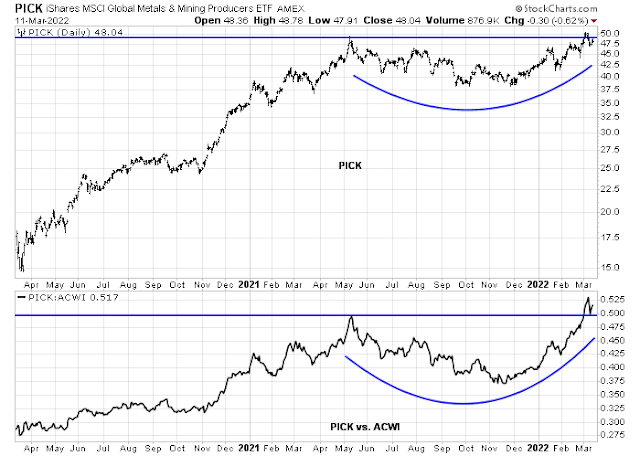

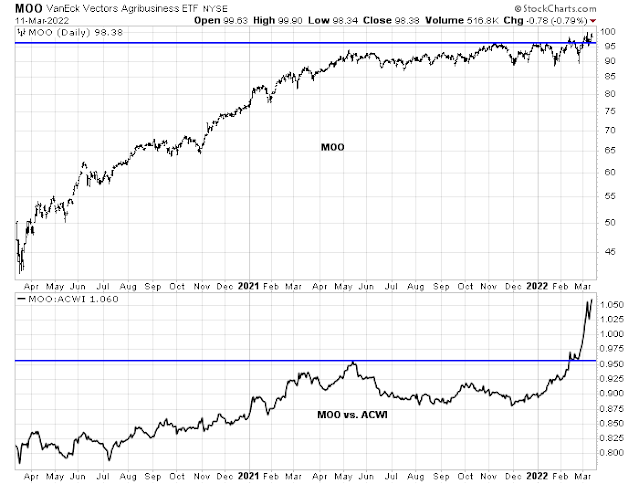

Other than the defensive sectors, the part of the market that’s showing leadership is commodity-related resource extraction industries. This is an indication that the market is undergoing a late-cycle phase led by inflation hedge vehicles.

The blemish to the late-cycle expansion narrative is China. China is a voracious consumer of raw materials and Beijing has undertaken some steps to stimulate its economy. However, the relative performance of Chinese material stocks is weak, indicating a lack of Chinese demand. Investors shouldn’t expect China to rescue the global economy.

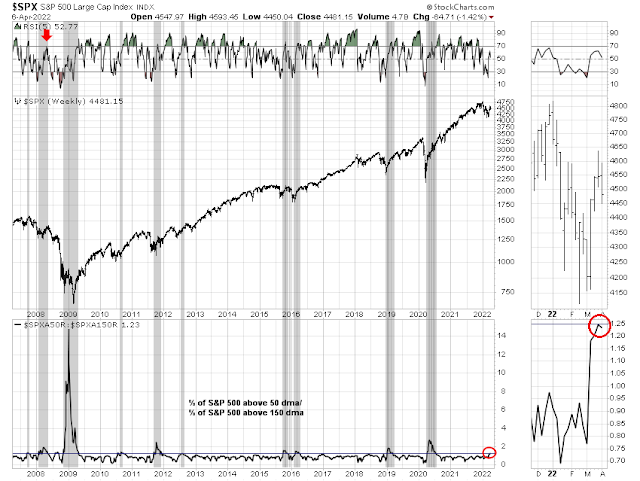

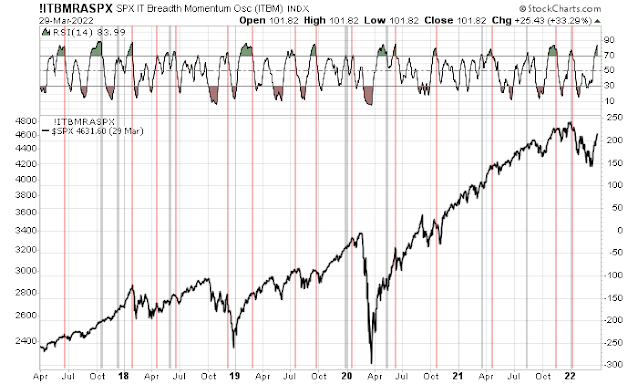

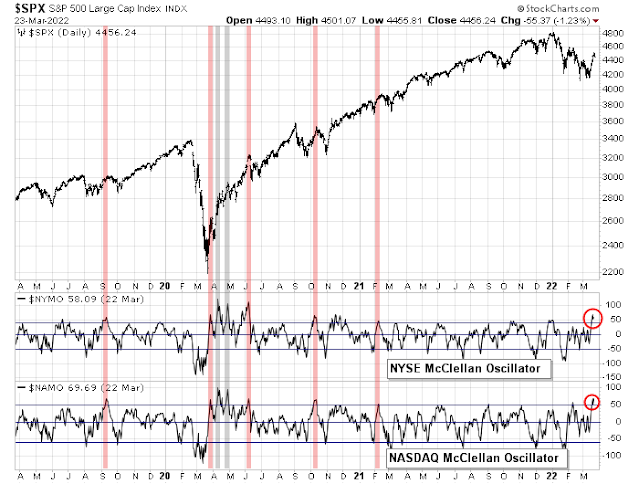

Weak equity risk appetite

In addition, equity risk appetite indicators, as measured by the relative performance of high beta to low volatility stocks and the equal-weighted relative performance of consumer discretionary to staples, are weak and flashing minor negative divergences to the S&P 500.

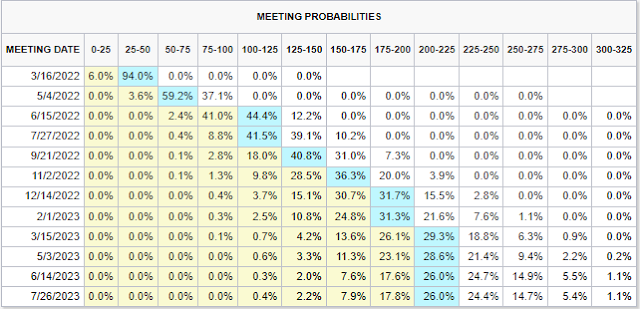

Hawkish central bankers

Lastly, central bankers are turning hawkish everywhere.

In addition, former New York Fed President Bill Dudley wrote a

Bloomberg Op-Ed which concluded that the Fed needs to hurt the stock and bond markets in order to bring inflation under control.

As [Jerome Powell] put it in his March press conference: “Policy works through financial conditions. That’s how it reaches the real economy.”

He’s right. In contrast to many other countries, the U.S. economy doesn’t respond directly to the level of short-term interest rates. Most home borrowers aren’t effected, because they have long-term, fixed-rate mortgages. And, again in contrast to many other countries, many U.S. households do hold a significant amount of their wealth in equities. As a result, they’re sensitive to financial conditions: Equity prices influence how wealthy they feel, and how willing they are to spend rather than save.

Dudley concluded:

Investors should pay closer attention to what Powell has said: Financial conditions need to tighten. If this doesn’t happen on its own (which seems unlikely), the Fed will have to shock markets to achieve the desired response. This would mean hiking the federal funds rate considerably higher than currently anticipated. One way or another, to get inflation under control, the Fed will need to push bond yields higher and stock prices lower.

Financial conditions are far from showing signs of stress. Yield spreads widened but they recently narrowed again, indicating loose financial conditions. If Dudley is right, the Fed will need to tighten a lot more to break the markets.

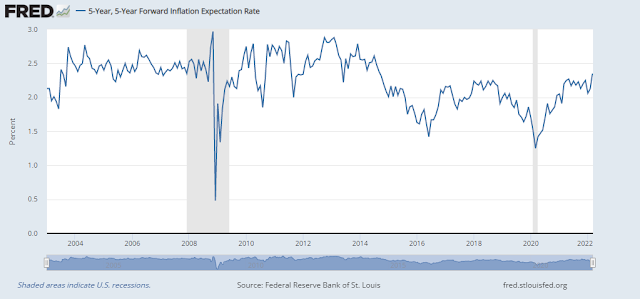

Good news on inflation?

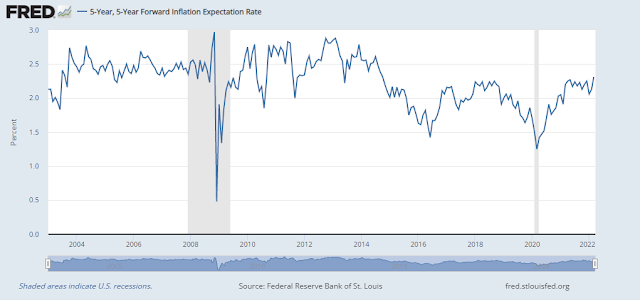

If Dudley is focused on inflation, some good news on inflation may be on the way. That’s the silver lining in all the dark bearish clouds. As the market openly worries about a repeat of the 1970’s, an analysis of different measures of CPI shows that sticky price CPI is tame while flexible price CPI has surged. By comparison, both were rising uncontrollably during the inflationary 1970’s.

The woes of the truckers and transportation stocks may be an indication that flexible price CPI is ready to retreat. China to US shipping volume is falling, indicating an easing in COVID-induced supply chain disruptions.

The drop in transportation volume is a manifestation of the bullwhip effect. When supply chain disruptions hit a market, the initial reaction is to horde inventory and over-order, which creates a ripple effect down the supply chain. As new supply appears, participants are caught with excess inventory and evaporating orders because their customers had over-ordered. This creates a boom-bust volatility effect in the supply chain as disruptions go down the supply chain.

This bullwhip effect can also be observed in the components of the March ISM Manufacturing report. The spread between new orders and production has fallen dramatically, indicating easing supply chain pressures.

Fed policy makers recognize these inflation dynamics. Goods inflation is expected to decline. The dual challenges are the additional supply chain disruption effects of the Russia-Ukraine war and the evolution of services inflation as consumers shift spending from goods to services as the pandemic eases.

Brent crude printed a

tombstone candle for the month of March, which may be indicative of a top. The price reversal needs to be confirmed by the next candle (in April), which is playing out so far. This is another sign that much of the war-related commodity price surge has peaked, which could feed into a welcome inflation surprise in the near future.

Job posting growth on Indeed are starting to stall, which may be a sign that the red-hot labor market is cooling.

The key indicators to watch in the coming months are non-farm payroll for signs of changes in job market pressures and the interaction between wages and inflation. Also, keep an eye on the evolution of inflation. The Fed is projecting a core PCE rate of 4.1% by December. Will inflation overshoot or undershoot that estimate?

The US Inflation Surprise Index is positive but decelerating. The CPI report on Tuesday will be a key test for the markets.

In conclusion, a review of a variety of market-based signals lead to the conclusion that risk asset prices are headed lower. The combination of hawkish central bank policy tightening into a cyclical downturn is the recipe for an equity bear market. The only hope for the bulls is better news on inflation which will slow the pace of accommodative policy removal and change the economy’s flight path into a soft landing.