It is said that while bottoms are events, but tops are processes. Translated, markets bottom out when panic sets in, and therefore they can be more easily identifiable. By contrast, market tops form when a series of conditions come together, but not necessarily all at the same time. My experience has shown that overly bullish sentiment should be viewed as a condition indicator, and not a market timing tool.

Two months has passed since I last published a post in a series of “things you don’t see at market bottoms”. That’s because market exuberance has significantly moderated. There are, nevertheless, signs of froth in non-US markets. Therefore I am publishing another post in the series. Past editions of this series include:

- Things you don’t see at market bottoms, 23-Jun-2017

- Things you don’t see at market bottoms, 29-Jun-2017

- Things you don’t see at market bottoms, bullish bandwagon edition

- Things you don’t see at market bottoms, Retailphoria edition

- Things you don’t see at market bottoms, Wild claims edition

- Things you don’t see at market bottoms, No fear edition

- Things you don’t see at market bottoms, Paris Hilton edition

- Things you don’t see at market bottoms, Halloween edition

- Things you don’t see at market bottoms, CFD edition

- Things you don’t see at market bottoms: Rational exuberance edition

- Things you don’t see at market bottoms: Retail stampede edition

I reiterate my belief that this is not the top of the market, but investors should be aware of the risks where sentiment is getting increasingly frothy. Much of the froth can be found across the Pacific in China, starting with the China bears’ favorite chart.

Rising default risk

China’s ballooning debt has been well managed so far because much of the debt, whether issued by banks, state owned enterprises (SOEs), or local governments (LGFVs) have carried an implicit central government guarantee. It was said that Beijing would “never” allow the debt to default.

Bloomberg reported that the risks of defaults are now rising and there would be no Beijing Put:

As China’s President Xi Jinping steps up efforts to rein in excessive borrowing, the nation’s corporate bond market faces rising default risks as weaker firms and local borrowers struggle to roll over obligations.

The latest salvo came last month, when the top economic planning body said it will step up scrutiny of the public works-related assets held by companies seeking to sell bonds. The National Development and Reform Commission, or NDRC, also said it would further regulate bond sales by public-private partnership projects.

President Xi has vowed to make controlling financial risks a priority, and former central bank governor Zhou Xiaochuan warned last year of a Minsky Moment, where asset values plunge following an era of unsustainable credit growth. The attempts to cut leverage already slowed expansion of the corporate bond market to 4.6 percent last year from 21 percent in 2016, according to data from the People’s Bank of China.

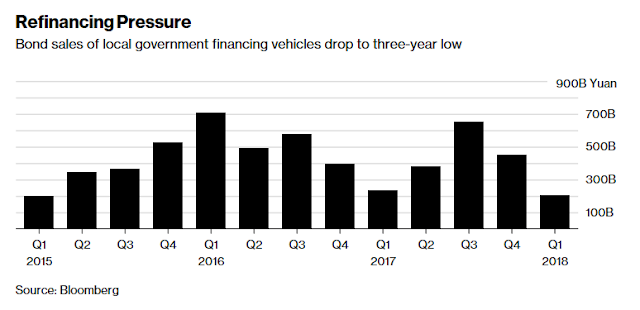

As a result, LGFV financings are dropping, and it is an open question as to how these local authorities can roll over their obligations in the future.

Companies tied to local projects are facing similar difficulties:

“Some companies which previously relied on external support to meet the criteria for bond issuance won’t be able to do so given the latest requirements,” said Qi Sheng, chief fixed income analyst at Zhongtai Securities Co. “It should be much more effective this time compared with similar notices before, as the current policy environment won’t allow any counter measures or a loosening in implementation.”

For now, this development is not fatal to the Chinese economy. Tightening credit conditions just raises risks.

Speaking of debt…

Speaking of debt, Here is one ominous observation that speaks for itself. Three of the top 10 Chinese unicorns are loan sharks (Sina article in Chinese).

The new Fragile Five

I had highlighted the new Fragile Five (see The new Fragile Five to avoid). Loomis Sayles had warned that these countries are the new Fragile Five, because of real estate bubbles that were partly blown because of Chinese hot money driving up property prices.

Cracks are starting to appear in five highly leveraged economies: Canada, Australia, Norway, Sweden and New Zealand. For several years following the global financial crisis, these five countries all shared a common theme—a multi-year housing boom, fueled by low interest rates, which resulted in very elevated levels of household debt.

This boom is starting to dissipate in all five markets. House prices have largely reversed course, be it slowing appreciation or outright decline. Moreover, this is occurring even as interest rates remain at or near record lows and labor markets continue to be robust. Importantly, this is a correction that many thought could not occur given the otherwise strong economic growth backdrop in these countries. But we take a long-term view of house prices, and began highlighting affordability problems in these markets several years ago.

I went on to point out that these countries share the common characteristic of being dependent on natural resource exports. Should the Chinese economy slow because of a debt crisis, the economies of these countries would suffer disproportionately.

That is why, as a Canadian resident, I maintain some of my holdings in USD for precautionary purposes.