Preface: Explaining our market timing models

We maintain several market timing models, each with differing time horizons. The “Ultimate Market Timing Model” is a long-term market timing model based on the research outlined in our post, Building the ultimate market timing model. This model tends to generate only a handful of signals each decade.

The Trend Model is an asset allocation model which applies trend following principles based on the inputs of global stock and commodity price. This model has a shorter time horizon and tends to turn over about 4-6 times a year. In essence, it seeks to answer the question, “Is the trend in the global economy expansion (bullish) or contraction (bearish)?”

My inner trader uses the trading component of the Trend Model to look for changes in direction of the main Trend Model signal. A bullish Trend Model signal that gets less bullish is a trading “sell” signal. Conversely, a bearish Trend Model signal that gets less bearish is a trading “buy” signal. The history of actual out-of-sample (not backtested) signals of the trading model are shown by the arrows in the chart below. Past trading of the trading model has shown turnover rates of about 200% per month.

The latest signals of each model are as follows:

- Ultimate market timing model: Buy equities

- Trend Model signal: Risk-on

- Trading model: Bullish

Update schedule: I generally update model readings on my site on weekends and tweet mid-week observations at @humblestudent. Subscribers will also receive email notices of any changes in my trading portfolio.

Trumponomics: The bear case

In last week’s post (see How Trumponomics could push the SPX to 2500 and beyond), I laid out the bull case for stocks under a Trump administration and how stock prices could appreciate 20% in 2017, assuming everything goes right. This week, I outline the bear case, or how Trumponomics keeps me awake at night.

Candidate Trump has said many things on the campaign trail, some of which are contradictory. President-elect Trump’s cabinet is taking shape and we are now getting some hints about policy direction. Nevertheless, there are a number of contradictions in his stated positions whose unexpected side-effects that could turn out to be equity bearish:

- Legislative tax cut disappointment

- A contradiction in fiscal policy vs. trade policy

- Geopolitical friction with China

- Rising geopolitical risk

- Loss of market confidence

- A possible collision course with the Federal Reserve

In this post, I will discuss each of these points, and I will end on how I believe these contradictions are likely to be resolved by the market.

Will Congress pass the Trump tax cuts?

My last weekend’s post (see How Trumponomics could push the SPX to 2500 and beyond) assumes that Candidate Trump’s fiscal stimulus plans of tax cuts and corporate offshore cash repatriation tax incentives will be passed by Congress. However, there may be significant resistance from Republican budget hawks.

The appointment of Mick Mulvaney as the head of OMB makes the passage of wholesale tax cuts less likely, as Mulvaney is known as a balanced budget advocate during his term in Congress (via Business Insider):

Trump has promised large tax cuts for both individuals and corporations, which would make increasing revenue difficult. He has also said he wants to invest heavily in the military, so cutting spending elsewhere may be difficult.

Debt always seemed to make sense given cheaper debt-servicing costs enabled by low interest rates, but now with Mulvaney at the helm of the OMB, this option may not be as likely.

“This significantly lowers the probability of big unfinanced tax cuts and big unfinanced infrastructure spending,” Torsten Sløk, the chief international economist at Deutsche Bank, said in a note to clients after the announcement.

This does not mean stimulus won’t happen; ultimately, Trump is still in charge and can push Mulvaney to include the spending in the budget or make the math work to get an infrastructure plan going. Mulvaney may be able to provide some pushback, however, Mills said.

“President-elect Trump’s statement announcing the nomination highlighted Rep. Mulvaney’s conviction to address the federal debt and pledged ‘accountability’ in federal spending in his Administration,” Mills concluded. “This leads us to believe that Mulvaney could push back against the significant stimulus spending.”

In effect, the stock market is priced for the perfection of Trump’s promised tax cuts. What happens if they don’t materialize as expected?

Fiscal policy vs. trade policy

Even if Trump gets his tax cut package passed, BAML foreign currency strategist David Woo recently appeared on Bloomberg and outlined a dilemma for the Trump team. Candidate Trump has made fiscal policy and trade policy the centerpieces of his campaign. But there is an inherent contradiction between the two.

His fiscal policy of tax cuts and incentives for offshore tax repatriation is very bullish, both for the US equities, the American economy, and the US Dollar. However, his trade policy of slowing or reversing the offshoring effect and enhancing trade requires a weaker USD. So what does he want? A strong Dollar or weak Dollar?

Mohamed El-Arian agrees with David Woo’s assessment of the strong vs. weak Dollar dilemma:

Though the US economy is doing much better than most of the other advanced economies, it is not yet on sound enough footing to withstand a prolonged period of a substantially stronger dollar, which would undermine its international competitiveness – and thus its broader economic prospects. Augmenting the risk is the prospect that such a development could spur the Trump administration to follow through on protectionist rhetoric, potentially undermining market and business confidence and, if things went far enough, even triggering a response from major trade partners.

Central to the dilemma is Trump`s view of China`s competitive position. One of Candidate Trump’s principal targets has been the trade behavior of China. The PBoC has been taking active steps to strengthen the CNYUSD exchange rate, which weakens their trade position. However, if a Trump administration were to label China as a currency manipulator, it would give cover for Beijing to actually devalue their currency in line with market forces, which sets the stage for a trade war that no one wants.

Even worse, Business Insider pointed out that a weakened yuan isn’t helping Chinese exports, which may be a signal that the China export engine is losing its competitive edge.

The yuan has been reaching multi-year lows, and the dollar’s recent strength after Donald Trump won the U.S. presidential election isn’t helping either. What’s even more worrisome is that October export numbers show that a weak yuan isn’t helping the Chinese economy.

“Stripping out the impact of yuan depreciation, exports in dollar terms fell 7.3% year on year in October after a 10% drop in September,” wrote Bloomberg’s Tom Orlik in a recent note. “Imports slipped 1.4% after a 1.9% decline. China’s trade surplus in dollar terms was $49 billion, up from $42 billion. The surplus is in contrast to a larger-than-expected $45.7 billion decline in China’s foreign reserves in October, indicating quicker capital outflows in the month.”

While diminishing growth in Chinese exports may sound like good news for the America First crowd, it also has the potential to set off a trade war through the devaluation channel if Trump were to label China a currency manipulator. Holger Zschaepitz at Die Welt observed that a cratering CNYUSD exchange rate could have global repercussions.

A weaker yuan would be the first shot in a possible trade war, followed by retaliation for possible US tariffs. Trump’s appointment of Peter Navarro, the author of Death by China, to head the newly created National Trade Council is particularly disconcerting. The chart below from Bloomberg shows the portion of sales that selected major American companies derive from China.

Consider, for example, Boeing (BA) which is the least exposed company on the list. In a trade war, The company claims that Chinese orders support 150,000 American jobs per year. (Who cares, that’s just a single month’s of Non-Farm Payroll job increases, right?) In addition, the WSJ reported that China is preparing a retaliatory response whose list includes Boeing, General Motors, and 30 million tons of soybeans imports from over 30 US states.

Geopolitical friction with China

It is unclear whether Trump’s belligerent attitude towards China is real, or if it represents an “art of the deal” posturing for bargaining purposes. Trump’s controversial telephone call with the Taiwan’s president Tsai Ing-wen crossed a red-line for the Chinese. Trump defended the call by stating that Taiwan could be used as a bargaining chip in US negotiations with China. In response, China flew a nuclear-capable bomber over the South China Sea as a signal that it is not to be intimidated.

If the Trump team does go down the China confrontation road, then it must be prepared to bear the consequences. You want help controlling North Korea’s nuclear ambitions? Forget it! You want the Chinese to refrain from using its UN Security Counsel veto in a vote against Iran? You’ve got to be kidding!

You get the idea.

In general, taking steps to batter an already fragile Chinese economy is in no one’s interest. China’s debt excesses are well known. Crash the Chinese economy, and it will push most of Asia and resource based economies, such as Brazil, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, into recession. Tanking Chinese capital goods demand would depress German exports and possibly topple the equally fragile eurozone economy. This domino effect of cascading economic crashes is not the kind of outcome anyone wants (see Why the next recession will be very ugly and How much “runway” does China have?).

Here is just one simple example of China`s economic fragility. In response to the Fed’s rate hike, the WSJ reported that Chinese bond market cratered. The South China Morning Post outlined four reasons why China is afraid of US interest rate increases:

- Yuan depreciation against US dollar deepened

- China forex reserves shrank quickly

- China’s stock market plunged

- Beijing started to reverse capital account opening process

The world is highly connected. You can’t just alter policy in one place without unexpected consequences showing up somewhere else. A China hard-landing could crash the global economy. The ensuing carnage has the potential to be another Lehman Crisis, or worse. Already, China is on the verge of implementing a tighter monetary policy, which raises the risks of an accident (via Bloomberg):

China’s leaders are pledging a harder push to rein in risk next year and emphasizing prudent and neutral monetary policy. With the Federal Reserve flagging a steeper interest-rate path, that sets the scene for the first U.S.-China tightening since 2006.

President Xi Jinping and his top economic policy lieutenants adjourned their annual planning conference Friday with a vow to safeguard the financial system and deflate asset bubbles. Maintaining stability and making progress on supply-side reform will be key 2017 themes, they said in a statement issued after the three-day Central Economic Work Conference.

“Policy makers are making clear that they’re determined to clamp down on speculation and will keep doing so next year,” said Wen Bin, chief research analyst at China Minsheng Banking Corp. in Beijing. “It’s very important to deflate the property bubble.”

To be sure, China is holding its 19th Party Congress in the autumn of 2017 and its timing will keep economic risk low for most of the year. The Party will do everything in its power to maintain the facade that growth is strong. Any hard landing, should it occur, won`t happen until Q4 2017 at the earliest.

Rising geopolitical risk

Another bearish factor for the market is rising geopolitical risk. A recent CNN Money post-election interview with Warren Buffett found the legendary investor to be bullish on America. However, he expressed reservations about the “temperament and judgment” of president-elect Trump when it came to WMDs.

More worrisome was Trump’s remarks about encouraging an arms race in nuclear weapons (via Reuters):

Trump had alarmed non-proliferation experts on Thursday with a Twitter post that said the United States “must greatly strengthen and expand its nuclear capability until such time as the world comes to its senses regarding nukes.”

MSNBC’s Mika Brzezinski spoke with Trump on the phone and asked him to expand on his tweet. She said he responded: “Let it be an arms race. We will outmatch them at every pass and outlast them all.”

In many ways, Americans have been spoiled by the history of their capital market returns. Many analysts have espoused a buy-and-hold discipline to equities, as long as the investor can bear the risk. That`s because the historical record shows that everything has turned out fine in the end, as evidenced by this chart from the Credit Suisse Global Investment Yearbook 2016 (annotations are mine).

But the hidden risk to capital returns has always been war and rebellion. Such episodes can turn the above US return pattern to the one below, even if you are a victor but the wars leave you exhausted and depleted.

Worst still, they can become like this, even for an economic and technology powerhouse like Germany. The real terminal value for German equities at $42 after 116 years may sound good, but they are dwarfed by the American results at $1271.

Or worst still, like this, when investors were far more concerned about personal survival than the value of their portfolios after cataclysmic events like revolution.

It would be overly simplistic to assert that Trump’s foreign policy by spur-of-the-moment Twitter is erratic and creates geopolitical instability. Thomas Wright explained in a thoughtful Foreign Policy article that the actual source of that instability comes from the tension between three distinct factions within the Trump administration. The three factions consist of America First, who counts Trump as its leader and is isolationist in outlook, the Religious Warriors, who sees America as locked in an existential conflict against the Islamic threat, and the Traditionalists from the foreign policy establishment. It is the tension between these three groups that create uncertainty about the direction of foreign policy:

These three factions—the America Firsters, the religious warriors, and the traditionalists—are mutually suspicious. But each also needs the others to check the third. Trump needs the religious warriors to prevent a mainstream takeover, but he fears they will drag him into a war against Iran. The religious warriors need Trump to achieve their objectives, but they also have no desire to collapse the U.S. alliance system. The traditionalists need both to check the radical impulses of the other.

The America that Trump inherits faces many geopolitical challenges. Former Swedish PM and diplomat Carl Bildt, writing in Project Syndicate, outlined the threats to the global order with a warning from Henry Kissinger, who has been a master practitioner of realpoltik:

Nearly two years ago, former US National Security Adviser and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger warned the Senate Armed Services Committee that, “as we look around the world, we encounter upheaval and conflict.” As Kissinger observed at the time, “the United States has not faced a more diverse and complex array of crises since the end of the Second World War.”

Bildt went on to fret about how the Trump administration might handle such a vast array of threats:

Against this volatile backdrop, the new Trump administration could very well embrace vastly different policies from what we have seen so far. Judging by the last few weeks, it seems as though we are going to have to live with a routine spectacle of international destabilization via Twitter…

Still, after years of rising turmoil and uncertainty, we have no choice but to assume that more “black swan” events are around the corner. From Donbas to North Korea to the Gulf region, there is no shortage of places where developments could take a shocking turn.

In normal times, the web of international relations affords enough predictability, experience, and stability that even unexpected events are manageable, and do not precipitate major-power confrontations. There have been close calls in recent decades, but there have not been any unmitigated disasters.

But those times may be over. We are entering a period of geopolitical flux: less stable alliances and increasing uncertainty. One should not exaggerate the risk of things spiraling out of control; but it is undeniable that the next crisis could be far larger than what we are used to, if only because it would be less manageable. And that is unsettling in itself.

The combination of Brexit, the Trump election, and anti-establishment threats in Europe has prompted Standard and Poor’s to issue an assessment concluding that political risk in developed markets is no different from the emerging markets (via Bloomberg):

“We believe it may no longer be possible to separate advanced economies from emerging markets by describing their political systems as displaying superior levels of stability, effectiveness, and predictability of policy making and political institutions,” wrote Moritz Kraemer, chief sovereign ratings officer, in a 2017 outlook report entitled “A Spotlight On Rising Political Risks.”

We have all become banana republics.

Loss of business confidence

Speaking of banana republics, Trump’s America is bearing an increasing resemblance to Indonesia under Suharto, or the Philippines under Marcos. Trump’s deals with Carrier to retain jobs in America, where he threatened retribution against any company offshoring jobs, or his tweets against Boeing (complaining about the cost of Air Force One) or against Lockheed Martin (complaining about the cost of the F-35) are examples of one-man rule by edict, rather than by a rules-based institutional system. My concern isn’t just about Trump’s policy by late night tweets, but whether individual decisions represent systematic policy initiatives with thoughtful consideration of policy consequences. Consider, for example, the above discussion about the conflict between fiscal policy and trade policy.

A country that is ruled by edict is a country subject to the whims of a single person. A country ruled by institutions have systems where property rights are upheld and there is high degree of regulatory certainty. Here is Tim Duy‘s reaction to the Trump threat of a tax on companies offshoring jobs:

President-Donald Trump’s renewed call for a 35% import tax on firms that ship jobs out of the United States triggered the expected round of derision from an array of critics, both on the left and the right. The critics are correct. It is indeed a terrible idea. One sure way to discourage job creation in the US is to guarantee that firms will be punished if they need to layoff employees in the future. It is just bad policy, plain and simple.

It`s not just bad policy, Trump has in essence accused American companies of treason and promised to punished offenders. In addition, his proposed initiative of a 35 % import tax sounds distinctly French and exemplifies the worst aspects of eurosclerosis. In France, employers cannot just arbitrarily hire someone. They have to prove that the company has sufficient resources to pay that employee and keep him around for a specific period. While employment law is very employee friendly, it creates a chilling effect for anyone who wants to expand into that jurisdiction. Moreover, such laws inhibit the natural process of creative destruction. In addition, Trump’s recent characterization of the “free market” as a “dumb market” in a Fox News interview does not exactly inspire business confidence (via Business Insider):

President-elect Donald Trump suggested that his administration would have to put a major tax on companies that relocate to other countries and then sell their goods in the US like “we’re a bunch of jerks.”

“What about the free market,” Wallace asked.

“It’s the dumb market,” he responded.

Why would anyone want to invest in France, Indonesia, or the Philippines America under those circumstances?

A collision course with the Fed?

Finally, the most recent hawkish interest rate raise by the Federal Reserve puts it on a potential collision course with the Trump administration. Not only did the Fed raise the Fed Funds target by a quarter point, it signaled that it is likely to raise rates three times, instead of two before the election. This would run counter to the stimulative effects of Trump’s tax cuts.

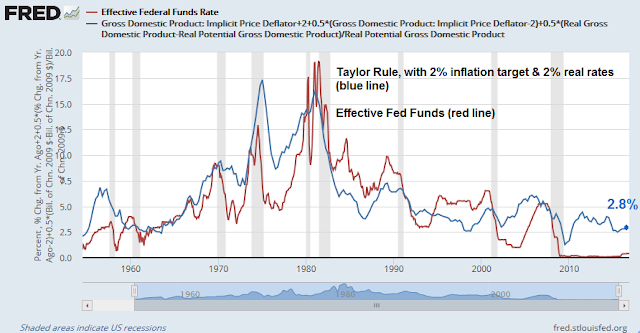

If Trump were to fill the two open seats on the Federal Reserve board with his hard-money cronies, they would likely favor a Taylor Rule like approach to setting interest rates, which would make the Fed even more hawkish. I recently wrote that my estimate of Taylor Rule target was 2.8%:

A more recent estimate of a neutral Taylor Rule target on a Bloomberg terminal turns out to be 4% (see Some perspectives on the new dot plot). A hard-money dominated FOMC would likely see interest rates faster than under a Yellen Fed.

I have no idea how this possible confrontation turns out, but the markets could freak out if the White House is on a collision course with the Fed. For some perspective, I conducted an unscientific Twitter poll early in the week asking Trump voters at what rate they would lend money to a government led by Donald Trump.

One respondent wrote:

hahahaha…. I would lend Trump money ONLY if secured by COLLATERAL WORTH MUCH MORE than the amount loaned.

That collateral would have to be something I could hold in my possession. Gold, for example.

Those poll results speak for themselves. If you voted for Trump and you are now equity bullish, and you are in the 3% or more camp, then ask yourself, “How much of an increase in earnings growth do you need in order to justify a 1% or more rise in bond yields?”

Bull vs. bear: What to do?

To summarize, my bull case for stocks has SPX earnings rising about 15-18% in 2017. If the P/E multiple stays the same, it would translate to a 15-18% boost to stock prices. On top of that, we have a potential buyback effect amounting to about 5% of index market cap to further raise the upside. If nothing goes wrong, it is easy to make a case that stock prices rise by 20% or more.

By contrast, the bear case consists a mainly of series of possible negative shocks, such as rising geopolitical risk, that raise the risk premium and depress the P/E multiple. There is no way to quantify how much the P/E multiple compresses in a bearish scenario, as much depends on the nature of the bearish trigger.

Here is how I would approach the equity market as 2017 unfolds. Historically, the seasonal pattern remains bullish until just after Inauguration Day. Until then, the market is focused on the positive effects of the Trump tax cuts. Stay bullish until then.

As the new Trump team takes over, risks will start to appear and the market is likely to experience some downside volatility. Right now, we have no idea of what the bearish trigger might be, so don’t ask me what the downside target is.

As the year progresses, I will be monitoring the precarious balance of the bull case of cyclical growth, tax cuts, and offshore cash repatriation tax holidays, against the bear case of mainly political and geopolitical risk of the Trump administration. In addition, I will be watching how recession risk develops (see Going on recession watch, but don’t panic!).

Under these circumstances, a blend of both fundamental and technical analysis is useful for guiding where stock prices are likely to go. From a fundamental and intermediate term perspective, as long as the global cyclical upturn remains intact, my inner investor is inclined to give the bull case the benefit of the doubt. At a tactical level, technical and sentiment analysis will be more useful for determining short-term peaks, bottoms, and other turning points.

The week ahead

Looking to the week ahead, the jury is out on market direction (see Santa Claus rally, or round number-itis). On one hand, next week is one of the most seasonally positive weeks for equities, and for small caps in particular.

On the other hand, Helene Meisler observed that a Bradley date, which is an estimate cyclical turning point in a market (not necessarily equities), occurs next week on December 28. In addition, Alex Rosenberg, writing at CNBC, pointed out that there may be a natural huhe man tendency for traders to book a gain as the stock market has had a good year. The selling from the “book a gain” behavior would serve to counteract next week’s positive seasonal effects.

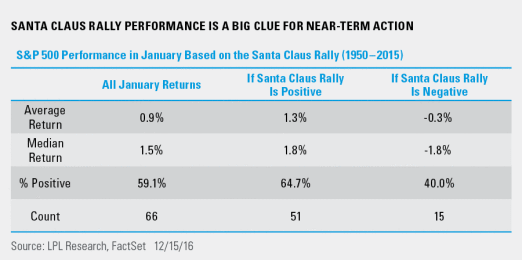

Finally, Ryan Detrick at LPL Research found that the success of the Santa Claus may be a window into the market’s January returns. Simply put, weak Santa Claus rallies tend to see weak January returns:

We’d put it like this; not all red Januaries have had a weak Santa Claus Rally during this period, but all weak Santa Claus Rallies have led to a red January. Over the past 20 years, stock market performance during the Santa Claus Rally has been negative five times and the following January was also red all five of those times.

Barring significant market developments, my plan is to start to lighten up on my long equity positions as Inauguration Day approaches. If I were to buy back into the market after a post-inauguration correction, my preference would be to own a buy-write index. The long position in the underlying index provides capital gains upside, and the probable higher level of market volatility will provide juicy premiums from call option writing.

Disclosure: Long SPXL, TNA

When looking at both the bull and bear cases there is a clearly more certainty around the bull pieces.

The Trump cabinet WILL cut taxes, repatriat overseas corporate money, favor oil and banking with rollbacks of regulation and generally be business friendly. The scale of these things is the only uncertainty.

The bear case revolves around what Trump’s personality MIGHT screwup in a POSSIBLE international situation down the road.

The bull case is here and now and a money maker. The bear case is ‘confirmation bias’ for those investor not in the Trump bull market and needing a reason why they are justified to have made that decision.