The Russia-Ukraine war has dealt an unexpected shock to the global economy and markets. Even as the world began an uneven recovery from the COVID Crash of 2020 and inflation pressures began to rise, the war has spiked geopolitical risk premiums and exacerbated supply chain difficulties and added more inflationary pressures. From an economic perspective, rising inflation and inflation expectations are forcing central bankers to react with more hawkish monetary policies, which raise recession risk.

The price of war

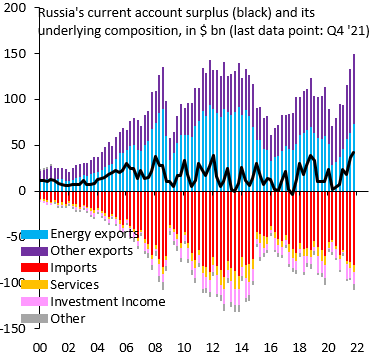

The conclusion of all these calculations is simple: As long as Russia can continue to export oil and gas, it can finance the revenue shortfalls generated by the sanctions for a long time. But the economic toll will be enormous: GDP will drop nearly 10% over the next 12 months alone and may not stop there.

But if Russia loses its oil and gas revenues, it will run out of money within one to two years.

While that analysis is correct from a top-down macro perspective, anecdotal reports indicate that sanctions are biting. Fortune cited a Ukrainian military social media release, whose information is unconfirmed by other sources, that Russian tank production has ground to a halt because of a parts shortage.

The country’s primary armored vehicle manufacturer appears to have run out of parts to make and repair tanks, according to a Facebook post by the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

Citing “available information,” it reported state-owned company Uralvagonzavod, which builds tanks such as the T-72B3, has had to temporarily cease production in Nizhny Tagil.

The Russian offensive has depleted its troop strength. The latest NATO estimate indicates that the Russian Army has lost 30-40K men, which includes killed, wounded, missing in action, and taken prisoner. It is, therefore, no surprise that Moscow has mobilized reserves, recruited Syrian fighters, and called for a draft. Anecdotal accounts from social media from Russian mothers’ groups indicate heightened anxiety among the middle-class of the draft for their teenage sons. There were also reports of shortages of staples like sanitary napkins and, more importantly, insulin.

In addition, Russia’s latest reported weekly CPI was up 1.93%, which puts CPI up an astounding 132% for the period of the war.

On the other hand, Russia has substantial leverage in terms of its exports as it is the substantial source of some key global commodities.

Both Russia and Ukraine are major exporters of grains, which threatens the global food supply. In particular, African countries are especially dependent on Russian and Ukrainian wheat, which increases the risk of global famine. The last episode of food insecurity coincided with Arab Spring. This raises the risk of geopolitical instability.

“Yes, we will end this dependency – as soon as possible. But to do this from one day to the next would mean plunging our country and the whole of Europe into a recession,” Scholz told the Bundestag lower house of parliament.

“Hundreds of thousands of jobs would be in danger. Whole branches of industry would be on the brink,” he said. “Sanctions should not hurt European states harder than the Russian leadership.”

A recent paper co-authored by a distinguished group of economists working both inside and outside Germany projected the effects of a sudden cutoff of Russian gas to Germany, based on the scenario that Germany loses 30% of natural gas supply and 8% of its primary energy supply.

Purely in the spirit of being conservative, we therefore postulate a worst-case scenario that doubles the number without input-output linkages from 1.5% to 3% or €1,200 per year per German citizen. This number is an order of magnitude higher than the 0.2-0.3% or €80-120 implied by the Baqaee-Farhi model. We should emphasize that this is an extreme scenario and we consider economic losses as predicted by the Baqaee-Farhi model to be the more likely outcome

Bear in mind that this is a worst-case scenario where there are no substitutes for Russian gas. A GDP shock of 1.5% to 3.0% is similar in magnitude to the COVID shock. It’s painful but manageable. While Berlin may balk at the price of a complete cutoff of Russian gas, Scholz could change his mind under a scenario of Russian escalation to the use of WMDs, especially if they’re on a civilian population.

In short, Ukraine and the West are engaged in a contest of pain with Russia. Pressures are building for a settlement. Will anyone blink?

What would peace look like?

The details of any peace agreement are beyond the scope of this analysis, but imagine that peace suddenly descended in Ukraine. What are the economic and market ramifications of this best-case scenario?

An analysis from the European Central Bank outlined a heatmap of supply chain pressures in the US and eurozone. Even before the war, supply chain bottlenecks were evident in a variety of sectors.

Supply chain problems aren’t going away even if peace broke out. As an example, Ukraine has two plants that are about 50% of the global source of neon, a key component in semiconductor manufacturing. One is in Mariupol, which has been flattened by Russian bombing. The other is in Odessa, which is under threat, but it has shut down production. In addition, Ukrainian farmers are unlikely to plant their spring crop, especially in fields that may be strewn with landmines. At best, Ukrainian grain production won’t return to full production in the next few years.

Energy prices are likely to remain elevated in energy sanctions remain in place. A recent Dallas Fed survey of oil patch operators was highly revealing. While most respondents replied that an $80 to $90 WTI price is enough to spur new investment, a full 29% replied that their investment decisions are not oil price dependent.

That’s because of increasing investor pressure to maintain capital discipline. There is also anecdotal evidence of a scarcity of capital in the oil patch at any price owing to the growing trend of ESG investment mandates.

Where does that leave Fed policy? That depends on how transitory the inflation effects of the war are. As an example, Cullen Roche pointed out that global container freight rates have flattened out.

If they were to stay flat, the annualized rate of change would begin to fall in Q2, which alleviates inflation pressure.

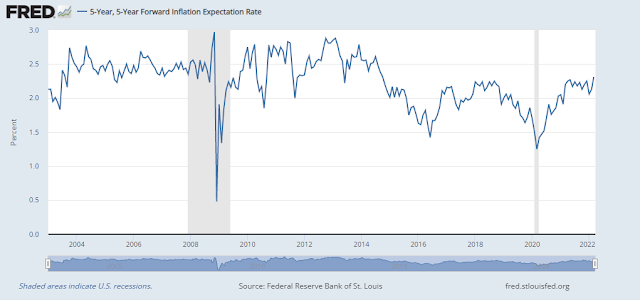

Notwithstanding the effects of the war, inflation should begin to fall from a combination of the transitory effects and monetary tightening. The wildcard is the degree and magnitude of the supply shocks from the war, and how they affect inflation and inflation expectations. The 5×5 forward inflation expectation is currently at the top of its range. An upside break would be a signal for the Fed to adopt an even more hawkish monetary policy.

The market is already expecting consecutive half-point rate hikes at the next two FOMC meetings, a total of 2.25% rate increases in 2022 and topping out in early 2023 at 2.50% to 2.75%. The disruption from the war could make things worse and force the Fed to engineer a recession in order to control inflation.

Recession odds are rising

In conclusion, a best-case scenario of a sudden peace agreement would leave the global economy exposed to additional supply chain aftershocks from the Russia-Ukraine war. I agree with John Authers, who wrote that all the good scenarios are gone. The markets are forward-looking and they are discounting a rising risk of recession, even though recession models are not calling for a recession just yet.

Bill McBride at Calculated Risk who relies mainly on housing market indicators for his recession calls, said that he isn’t even on recession watch yet. New Deal democrat, who monitors a series of coincident, short-leading, and long-leading indicators, characterized the economy as a weakening cycle overlaid with the negative effects of an exogenous shock from the war.

There are two separate dynamics operating on the economic indicators. One dynamic is a typical cyclical one of the Fed reacting to high inflation and low unemployment by raising rates, now that it has been convinced that inflation has not been “transitory.” The second dynamic is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the world’s reaction to it.

The first dynamic is primarily acting on the long leading indicators. Thus we see bond yields rising, and yield spreads tightening. In fact, several portions of the yield curve inverted Thursday and at least intraday Friday (most notably the 5 minus 3 year spread which briefly turned negative Friday, before closing ever so slightly positive). This dynamic is also why mortgage rates are negative, and at least partially why credit conditions have tightened.

As a result, the long leading forecast has turned neutral. A recession is possible one year from now, but not that likely yet…

The global economic reverberations of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the reactions to it, by way of sanctions, global oil supply, and also by businesses severing ties with Russia, is an exogenous event, just as the pandemic was in 2020. And just as with the pandemic in 2020, it could cause a recession without the normal procession of cyclical effects through the economy. But it is “transitory” in the sense that if and when the conflict resolves, the normal cyclical procession will reassert itself. Those cyclical processes, the other side of the pincer, continue to point towards a stall roughly at the beginning of next year.

- Overweight defensive sectors.

- Overweight quality stocks.

- Neutral weight resource extraction sectors such as energy and mining (upgrade).

- Neutral weight high-quality growth, which should be the next market leadership.

- Underweight value and cyclical stocks, such as financials, industrials, and non-FANG+ consumer discretionary.

I imagine a large fiscal deficit in Europe and the US in 2022 and 2023. The war is not going to be financed by taxes. They would continue printing money. Western countries have provided massive quantities of weapons from their stockpile. This has not been reflected in national accounts yet, since national accounts are prepared on a cash basis. Another source of fiscal deficit is humanitarian aid. I applaud the help western countries are providing to Ukraine, we just have to be aware of the impact. Another dynamic we have to consider is the military budget for coming years.

Once the conflict is resolved, it is unclear how the economic relationships between Russia and the West will continue. Russians have seized many assets and maybe considered uninvestible for a long term.

Another dynamic to consider is the impact of sanctions in companies earnings. Some companies suspended or abandoned their operations in Russia. I expect many impairment losses to be booked at the end of March

The world has been put on notice.

Defense spending, will be up.

Cybersecurity spending will be up.

Energy drillers (primarily US Oil and gas companies) will have to drill more which will take several years.

Non-oil resources/commodities: We can say goodbye to Russian supply.

Russia will be out of the bond market for many many years.

Inflation: There is a likelihood of permanent reset of inflation higher. Sure, the US Fed may induce a recession in the next few quarters, but once the recession is over, the same movie of higher prices will start, where we leave the movie today.

US supply chains: Depends on China, and Chinese manufacturing satellites. This is independent of war. Yes, this will moderate inflation pressures to a certain extent.

Why do we assume that inflation remains tame? After a secular decline in inflation from 1982, the assumption is that inflation remains tame. I am not so sure of this idea. Food grains, energy, materials, should see a longer term reset higher, at least until Russian supply can be replaced. Farm land prices should see even higher global prices. It may not cause credit events in major countries, but the probability of riots, food shortages, regime change, global anarchy increase outside the G7.

This narrative changes if Putin is not at the helm of Russia.

Lots of questions come to my mind . Russia seized hundreds of planes. What’s next? Ships?

D.V. mentions bonds, how about Russian stocks?

I thought about Russian stocks, but with many reputed companies, pulling out of Russia, marks makers walking away from RSX etc. this is not something I want to touch with a barge pole.

https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/cboe-halts-trading-vaneck-russia-etfs-2022-03-04/

I thought about Russian stocks, but with many reputed Multinational companies pulling out of Russia, market makers walking away from RSX etc. this is not something I want to touch with a barge pole.

https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/cboe-halts-trading-vaneck-russia-etfs-2022-03-04/

Cam wrote about slowly buying into TLT, a few weeks ago (once recession is on the horizon).