Preface: Explaining our market timing models

We maintain several market timing models, each with differing time horizons. The “Ultimate Market Timing Model” is a long-term market timing model based on research outlined in our post Building the ultimate market timing model. This model tends to generate only a handful of signals each decade.

The Trend Model is an asset allocation model which applies trend following principles based on the inputs of global stock and commodity price. This model has a shorter time horizon and tends to turn over about 4-6 times a year. In essence, it seeks to answer the question, “Is the trend in the global economy expansion (bullish) or contraction (bearish)?”

My inner trader uses the trading component of the Trend Model to look for changes in direction of the main Trend Model signal. A bullish Trend Model signal that gets less bullish is a trading “sell” signal. Conversely, a bearish Trend Model signal that gets less bullish is a trading “buy” signal. The history of actual out-of-sample (not backtested) signals of the trading model are shown by the arrows in the chart below. Past trading of the trading model has shown turnover rates of about 200% per month.

The latest signals of each model are as follows:

- Ultimate market timing model: Buy equities

- Trend Model signal: Neutral

- Trading model: Bearish

Update schedule: I generally update model readings on my site on weekends and tweet any changes during the week at @humblestudent. Subscribers will also receive email notices of any changes in my trading portfolio.

What now?

In the wake of the Brexit referendum surprise, I sensed that a lot of investment professionals were in shock and didn’t know how to react to the market turmoil. I have found that having the proper analytical framework focuses the mind. I found one tweet by the FT`s Gillian Tett particularly useful for investors.

That’s the critical question: Does Brexit represent a Lehman moment or LTCM moment for investors? In the former case, investors should de-risk portfolios and sell equities down to a minimum weighting in order to avoid severe losses. In the latter, investors have been handed a golden opportunity to buy stocks, Blink and the correction will be gone.

For traders, it’s entirely a different story, which I will also address in this post.

Assume no Brexit

Let’s start with the status quo and assume we saw a Remain result. What would the market look like?

I view the US equity market through the lens of the two components of the P/E ratio. What’s happening to E and its growth? And what’s the outlook for the P/E multiple?

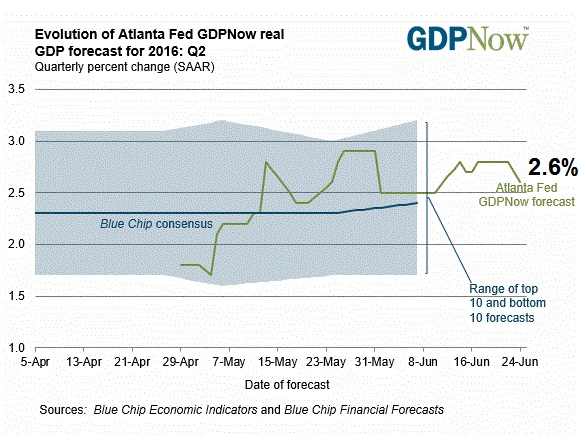

On the first question, growth looks ok through both top-down and bottom-up lenses. The US economy is motoring along just fine. The latest Atlanta Fed’s Q2 GDP nowcast shows growth at 2.6%, which is a retreat from last week’s 2.8% reading but still a healthy growth rate.

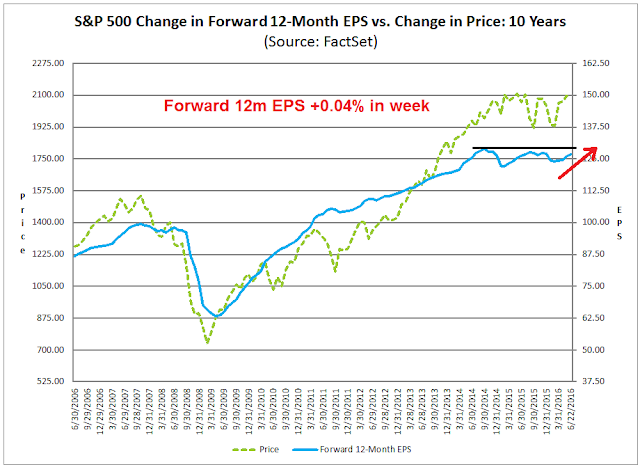

On a bottom-up basis, the latest update from John Butters of Factset shows that forward 12-month EPS is still growing and it’s on the verge of an upside breakout of a range that stretches back to 2014. Had Brexit vote resolved itself with a Remain result, the SPX might be surging to all-time highs.

The E/P ratio, which is the inverse of the P/E ratio, is the discount rate for corporate earnings. E/P can further be decomposed to an interest rate component and an expected growth component (recall that growth stocks command higher P/E ratios). The 2/10 yield curve had been steepening in the week before the Brexit vote, which is reflective of expectations of higher interest rates and better growth.

Had we seen a Remain vote, such a backdrop would be regarded as mildly bullish for US equities. Arguably, the Fed would have been getting ready to raise rates should it see reasonable Job Reports in the next month or two.

Brexit impact

The Leave vote changed everything. But instead of panicking and being frozen by the red on the screen, let’s take a deep breath and consider how our mildly bullish scenario for equities has changed by decomposing the effects of the vote.

- Direct effect on US equities and economy

- Indirect market effect on US equities and economy

- Financial contagion

- Political contagion

Direct effects are low

The direct impact of Brexit is relatively small. The immediate impact of the vote will likely see the UK economy go into recession, but the UK represents roughly 4% of global GDP. Does it matter that much to the US economy, or to US companies in aggregate, if an economy across an ocean about the size of California goes into recession?

Mixed indirect impact

The indirect impact is more mixed. The ensuing market panic saw a dramatic fall in the British Pound (GBP) and the USD rise on a trade-weighted basis as investors piled into safe haven US Treasury assets. On one hand, a rising USD is a negative for US economic growth as its strength hurts exporters and acts as a form of monetary tightening. As an example of the effects of the rising USD, this analysis from Factset shows that Q2 results showed that both EPS and revenue growth was lower for exporters compared to domestic companies.

To quantify the offsetting effects of a rising USD and falling bond yields, Torsten Slok at Deutsche Bank used the Fed’s model for modeling such shocks and found the following results:

- A 10% gain in the trade-weighted dollar for one year would lower US economic growth by 0.4%, and by 1.5% over three years.

- A 1% drop in the yield on the 10-year UST note would raise GDP by 0.4% over one year.

Financial contagion: LTCM or Lehman?

By contrast, the Fed managed to contain the LTCM crisis by arm twisting a group of investment dealers to support the troubled hedge fund, Long Term Capital Management. Over the course of a weekend, the Fed had figuratively locked the major heads of investment firms in a room and told them not to come out until they had figured out how they were going to spread the pain around the table.

It appears that the central bankers of the world know how to deal with potential financial crises. G-7 ministers and central bankers released this statement in the wake of the Leave vote:

We recognize that excessive volatility and disorderly movements in exchange rates can have adverse implications for economic and financial stability.

G7 central banks have taken steps to ensure adequate liquidity and to support the functioning of markets. We stand ready to use the established liquidity instruments to that end.

We will continue to consult closely on market movements and financial stability, and cooperate as appropriate.

The Bank of England released the following statement:

To support the functioning of markets, the Bank of England stands ready to provide more than £250bn of additional funds through its normal facilities. The Bank of England is also able to provide substantial liquidity in foreign currency, if required.

The European Central Bank also went into crisis mode with the following statement:

The ECB stands ready to provide additional liquidity, if needed, in euro and foreign currencies.

The ECB has prepared for this contingency in close contact with the banks that it supervises and considers that the euro area banking system is resilient in terms of capital and liquidity.

The Federal Reserve also follow suit:

The Federal Reserve is carefully monitoring developments in global financial markets, in cooperation with other central banks, following the results of the U.K. referendum on membership in the European Union. The Federal Reserve is prepared to provide dollar liquidity through its existing swap lines with central banks, as necessary, to address pressures in global funding markets, which could have adverse implications for the U.S. economy.

The intent is to flood the global financial system with liquidity. With so much resources brought to bear on this financial earthquake, an LTCM-style event is a far more likely outcome than a repeat of the Lehman meltdown.

Incidentally, you can forget about a July or September rate hike. Current market expectations show a higher probability of a rate cut than rate hike for every FOMC meeting as far as the eye can see. At a minimum, the first rate hike is highly unlikely to happen before the December meeting.

Political contagion tail-risk

On the surface, the actions of central bankers and G7 finance ministers are likely to contain any financial contagion from the worst effects of a Brexit vote. However, the risk of political contagion in Europe may be enough to keep Brexit risk in the headlines. Such a development can elevate risk premiums for some time, which would result in choppy range-bound markets until a solution can be found. Get ready for another summer of European theater. If Puccini was still alive, he would author an opera about the EU where characters named Merkel, Tsipras and Draghi would be singing arias.

To understand this drama, you need to understand the EU rules of Brexit, the players and their agendas. Under Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, a member state can ask to leave and can have up to two years to negotiate the terms of exit, but it is up to the member state to invoke Article 50 and no one else.

The first player is UK Prime Minister David Cameron, who announced that he would be stepping down as Conservative party leader (and PM) in October. He also stated that he would leave the next PM to notify the EU of the country’s intention to invoke Article 50. Cameron’s move has several implications. It buys him and the country some extra time to either negotiate or delay as the two year clock doesn’t start ticking until the UK government notifies the EU. In addition, a party leadership fight could split the Conservative ranks sufficiently that the new leader and PM may not have the votes to pass a parliamentary resolution to invoke Article 50. Such an outcome would like result in new elections, which creates even more delays.

In Brussels, we have the EU leadership and establishment, who is eyeing the Brexit vote warily. Euroskeptic parties have been springing up everywhere. If enough of them gain power, it could kill the European Project altogether (see my recent post The Brexit Pandora’s Box). The most immediate threat is an election in Spain this Sunday, where the anti-establishment Podemos party could become part of a coalition government (see this excellent Pimco summary about the Spanish election). Longer term, Marine Le Pen, who heads the anti-EU Front National, is making a strong bid to become the next President of France in elections to be held in May 2017. The election of Le Pen would drive a stake through the heart of the Franco-German European consensus and could spell the death of the EU.

The current EU leadership and establishment therefore has strong incentives to make an example of the British to show that anyone who tries to leave will suffer painful consequences. It was with those objectives in mind that in the morning of Friday, June 24, the European Commission issued the following statement:

We now expect the United Kingdom government to give effect to this decision of the British people as soon as possible, however painful that process may be. Any delay would unnecessarily prolong uncertainty. We have rules to deal with this in an orderly way. Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union sets out the procedure to be followed if a Member State decides to leave the European Union. We stand ready to launch negotiations swiftly with the United Kingdom regarding the terms and conditions of its withdrawal from the European Union. Until this process of negotiations is over, the United Kingdom remains a member of the European Union, with all the rights and obligations that derive from this. According to the Treaties which the United Kingdom has ratified, EU law continues to apply to the full to and in the United Kingdom until it is no longer a Member.

As agreed, the “New Settlement for the United Kingdom within the European Union”, reached at the European Council on 18-19 February 2016, will now not take effect and ceases to exist. There will be no renegotiation.

Translation: Invoke Article 50 asap. Oh, and that “new settlement” we offered you to stay in Europe? Forget about it.

The Guardian reported that both the European Parliament president and European Commission president reiterated the same message, “No games! We want the two year clock to start ticking now.”

Martin Schulz, the president of the European parliament, told the Guardian that EU lawyers were studying whether it was possible to speed up the triggering of article 50 of the Lisbon treaty – the untested procedure for leaving the union.

As the EU’s institutions scrambled to respond to the bodyblow of Britain’s exit, Schulz said uncertainty was “the opposite of what we need”, adding that it was difficult to accept that “a whole continent is taken hostage because of an internal fight in the Tory party”.

“I doubt it is only in the hands of the government of the United Kingdom,” he said. “We have to take note of this unilateral declaration that they want to wait until October, but that must not be the last word.”

EU referendum as it happened: Juncker calls for start to Brexit negotiations

Schulz’s comments were partially echoed by the president of the European commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, who said he there was no reason to wait until October to begin negotiating Britain’s departure from the European Union.

“Britons decided yesterday that they want to leave the European Union, so it doesn’t make any sense to wait until October to try to negotiate the terms of their departure,” Juncker said in an interview with Germany’s ARD television station. “I would like to get started immediately.”

Standing in the wings and watching this drama are Marine Le Pen (France), Geert Wilders (The Netherlands), Beppe Grillo (Italy) and the leaders of other anti-EU protest parties as they wait for their turn in the limelight. One wrong step – and the markets could freak out again over the election of another anti-establishment party in Europe.

Until these risks are resolved, which will likely be done in back rooms, expect the financial markets to remain on edge.

The weeks and months ahead

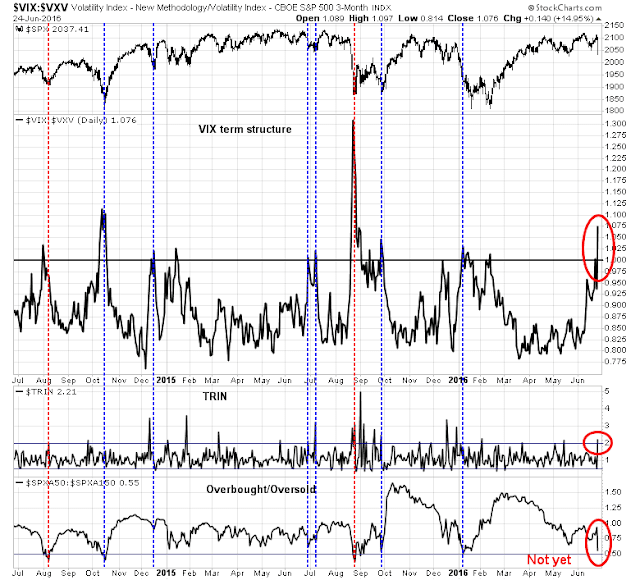

From a trader’s perspective, the Brexit wildcard makes trading a treacherous activity as markets will be volatile because of event risk. Readings are sufficiently oversold that short-term downside equity risk is likely to be limited and the market could bounce at any time. My Trifecta Bottom Spotting Model, which has shown an uncanny record of spotting short-term market bottoms, flashed an “exacta” buy signal as of Friday’s close. The model is based on the following three components. An exacta signal occurs if two of the components are triggered within a week of each other and a trifecta signal occurs if all three are triggered:

- VIX term structure is inverted: When the ratio of 1-month VIX (VIX) and 3-month VIX is above one, it indicates a high level of market fear.

- TRIN above 2: When TRIN is over 2, it is an indication of indiscriminate forced selling by either risk managers or margin clerks – and often marks a capitulation bottom.

- Intermediate term overbought/oversold: When the intermediate term OBOS is below 0.5, the stock market is oversold and stretched to the downside.

Even if we were to discount the Spanish election effect on TRIN, other technical indicators are supportive of a near-term bounce. These breadth measures from IndexIndicators show that the market is sufficiently oversold that a bounce is warranted.

Rocky White at Schaeffer’s Research studied past VIX spikes, as measured by the VIX ETN VXX, and found that events like Friday’s tended to resolve themselves bullishly.

On the other hand, intermediate term indicators like Fear and Greed are not fearful enough to mark a bottom, which tells me that any rally next week will probably be followed by a re-test of the lows.

The McClellan Summation Index (common stock only: middle panel, NYSE all issues: bottom panel) is also telling a story of a market that is insufficiently oversold for an intermediate term bottom.

My inner investor views this volatility as a gift from the market gods and he will be opportunistically accumulating equities at these levels. He gives the last word to former IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard, who summarized the current episode of market panic this way:

Much of what we have seen today, however, from the decrease in yields on long US Treasury bonds to the appreciation of the yen to the very large decline in some stock markets reflects an abrupt increase in global market risk aversion. Had risk aversion remained the same, there is little reason why Japan, for example, should have been much affected by the exit vote. Movements in market risk aversion can, however, be very powerful drivers of financial markets, and financial markets can move economies. If “risk off” lasts long enough, the global adverse effects of the vote may be very large.

Will it last? My guess, based on past episodes (although none quite as serious as this one), is not for very long, unless there are some undetonated financial bombs on the verge of exploding. The optimism of markets about the fate of “Remain” in the days preceding the vote may have led some hedge funds to make large bets and potentially run into trouble. Or markets may decide some euro periphery country is the next dangerous spot and requires much higher spreads on its debt, which the European Central Bank (ECB) is then unwilling or unable to control. If, however, it looks after a week or two as if no one did anything too stupid, and the central banks appear to have things under control, I would expect risk aversion to slowly decrease, markets and currencies to largely recover, and the fires to be mostly limited to the United Kingdom, and to a lesser extent, the European Union. At least, until the next referendum… .

My inner trader was stopped out of his long positions at the open on Friday and he is waiting out the volatility and waiting for the dust to settle.

This is a perfect case of “I don’t know” is the reason not to try for the maximum result over the next few weeks. There are too many unknowns.

From an equity investment standpoint the known factor is that ‘lower for longer’ is pretty much a sure thing for interest rates. That means the dividend ETFs will outperform the market. The SDY was down about 1% less the the S&P 500 on Friday for example.

If one is bullish simply go long strong dividend investments.

If one is bearish or uncertain put on a hedged position long dividend US ETFs and short the S&P. Leverage it to the level of your bearishness or bearishness and risk tolerance.

Long and short across international markets and currencies is several levels up the scale but can be done relatively easily with ETFs that trade in the U.S.

Ken,

If the British exit is followed by other countries, and the EU fails, we could see your moonless world for a very, very long time.

Get out of my head!

Developed world markets are in a long-term bear market, punctuated by brief, sharp, bear market rallies. Don’t touch this one until sentiment gets very bearish. Interestingly, long-term momentum looks horrible for each country in the EU except the UK, which looks like it wants to bottom!