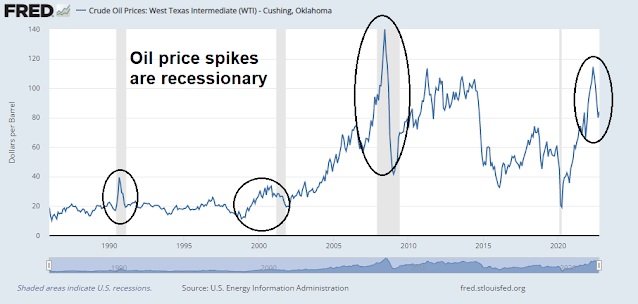

The recent OPEC+ decision to cut oil output by 2 million barrels per day is giving me a case of PTSD from a Yom Kippur long ago. In October 1973, the stock market was just getting over a case of Nifty Fifty growth stock mania. Arab armies, led by Egypt and Syria, made a surprise attack on Israel on Yom Kippur and overwhelmed the surprised defenders. The Israelis eventually prevailed in the conflict with US help. Arab oil-exporting countries responded with an oil embargo that spiked energy prices and caused a deep recession. The stock market fell roughly -50% on a peak-to-trough basis before recovering.

Fast forward to 2022. Instead of the Nifty Fifty, we have the FANG+ mania, which may be show signs of fading. Instead of a Middle East war, we have the Russo-Ukraine war. Instead of an Arab Oil Embargo, Russia has weaponized energy, mostly against the EU. Despite much lobbying by Washington, this year’s Yom Kippur brought an OPEC+ surprise. The organization made a decision to cut oil output by 2 mbpd. While the cut isn’t as bad as it sounds because a number of OPEC members aren’t producing at capacity, the decision nevertheless shows that the US and Europe have no allies within OPEC. As a consequence, Street analysts are scrambling to raise their oil price forecasts, and higher energy prices are likely to put pressure on the Fed to stay hawkish.

Will investors see a repeat of the 1973-1974 bear market in 2022-2023?

Recession ahead?

Notwithstanding the pressure from higher energy prices, the cyclically sensitive housing sector is tanking and signaling a slowdown. As mortgage rates (red line, inverted scale) rise, it’s difficult to see how the US economy can avoid a recession, especially against a tight monetary policy backdrop.

The Lehman Crisis loophole

Once central banks undergo a hiking cycle, they usually don’t stop until they judge that inflation is under control. The only loophole to that rule is a threat to financial stability, in the manner of a Lehman Crisis.

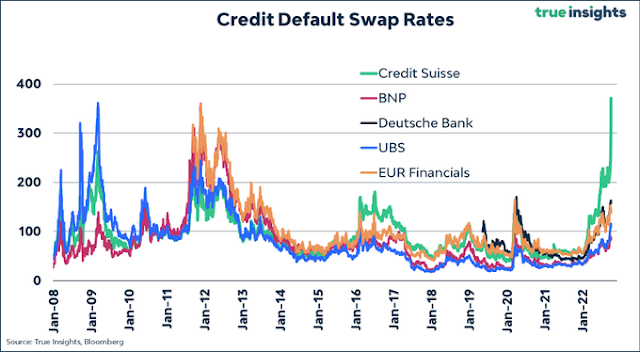

Rumblings began a week ago out of a report from ABC Australia that a credible source indicated that an unnamed large investment bank was on the brink of failure. Speculation turned to Credit Suisse, whose credit default swap rates had spiked, but the CDS rates of other European financials were also under considerable stress.

These circumstances turned to hope of a dovish pivot from the Fed. Already, three major central banks, the BOJ, the PBOC, and the BOE, have found it necessary to intervene in their bond markets. Hopes rose further when the RBA raised rates by 25 bps, which was less than the expected 50 bps, but dashed a day later when the RBNZ hiked by 50 bps and said it was considering raising rates even higher. Nevertheless, markets went risk-on last week in hopes that Credit Suisse could be the European Lehman Moment and force the Fed to pivot to a less hawkish policy?

There have been a flood of Fed speakers last week, and the message was clear. Don’t expect a dovish pivot. Fed Vice Chair Lael Brainard addressed the question of financial stability in a timely

speech. She acknowledged how the Fed’s tight monetary policy may be affecting America’s trading partners [emphasis added]:

Tightening in financial conditions similarly spills over to financial conditions elsewhere, which amplifies the tightening effects. These spillovers across jurisdictions are present for decreases in the size of the central bank balance sheet as well as for increases in the policy rate. Some estimates suggest that the spillovers of monetary policy surprises between more tightly linked advanced economies such as the United States and Europe could be about half the size of the own-country effect when measured in terms of relative changes in local currency bond yields.

The Fed is “attentive to financial vulnerabilities” of other countries:

We are attentive to financial vulnerabilities that could be exacerbated by the advent of additional adverse shocks. For instance, in countries where sovereign or corporate debt levels are high, higher interest rates could increase debt-servicing burdens and concerns about debt sustainability, which could be exacerbated by currency depreciation. An increase in risk premiums could kick off deleveraging dynamics as financial intermediaries de-risk. And shallow liquidity in some markets could become an amplification channel in the event of further adverse shocks.

In the end, however, she pushed back against expectations of a dovish pivot by the Fed [emphasis added]:

In the modal outlook, monetary policy tightening to temper demand, in combination with improvements in supply, is expected to reduce demand–supply imbalances and reduce inflation over time…It will take time for the full effect of tighter financial conditions to work through different sectors and to bring inflation down. Monetary policy will need to be restrictive for some time to have confidence that inflation is moving back to target. For these reasons, we are committed to avoiding pulling back prematurely. We also recognize that risks may become more two sided at some point…Proceeding deliberately and in a data-dependent manner will enable us to learn how economic activity and inflation are adjusting to the cumulative tightening and to update our assessments of the level of the policy rate that will need to be maintained for some time to bring inflation back to 2 percent.

The

WSJ reported that New York Fed President John Williams compared today’s inflation dynamics to an onion:

Mr. Williams compared inflation to an onion, with the prices of globally traded commodities such as lumber, steel, and oil, serving as the outer layer, and durable goods such as appliances, cars, and furniture serving as a middle layer. Declining commodities prices and improving supply chains should slow inflation for many goods, Mr. Williams said..

Underlying inflation pressures, or what Mr. Williams referred to as the innermost layer of the onion, have risen briskly and are unlikely to weaken without the Fed taking action to slow the economy with higher interest rates.

“Therein lies our biggest challenge…Inflation pressures have become broad based across a wide range of goods and services,” Mr. Williams said. “Demand for labor and services is far outstripping available supply. This is resulting in broad-based inflation, which will take longer to bring down.”

Fed Governor

Christopher Waller repeated the mantra of staying on the hawkish path and pushing back on expectations of a dovish pivot.

So, as of today, I believe the stance of monetary policy is slightly restrictive, and we are starting to see some adjustment to excess demand in interest-sensitive sectors like housing. But more needs to be done to bring inflation down meaningfully and persistently. I anticipate additional rate hikes into early next year, and I will be watching the data carefully to decide the appropriate pace of tightening as we continue to move into more restrictive territory.

In considering what might happen to alter my expectations about the path of policy, I’ve read some speculation recently that financial stability concerns could possibly lead the FOMC to slow rate increases or halt them earlier than expected. Let me be clear that this is not something I’m considering or believe to be a very likely development.

Fed Governor

Lisa Cook also stayed with the party line, “Inflation is too high, it must come down, and we will keep at it until the job is done.”

The September Jobs Report solidified market expectations of the Fed’s continued hawkish path. Headline NFP slightly beat expectations at 263,000 (250,000 expected). The unemployment rate unexpected fell from 3.7% to 3.5%, mainly because of a decline in the participation rate. However, average hourly earnings decelerated from 5.2% to 5.0%, indicating that wage pressures are under control. Market expectations of the trajectory of the Fed Funds rate were largely unchanged: A 75 bps hike at the November meeting, 50 bps hike at the December meeting, and a plateau of 450-475 bps in the Fed Funds rate in 2023.

In summary, the Fed’s is determined to “keep at it until the job is done”. That determination is evidenced by the unusual divergence between the nominal 5-year Treasury yield and 5-year breakeven rates.

There will be pain

What does this mean for equity investors? The stock market fell about -50% on a peak-to-trough basis during the 1972-1974 bear market. The combination of rising energy prices and a determined and hawkish Fed has the potential to spark a deep recession. I pointed out that an estimate of downside potential for the S&P 500 was a peak-to-trough drawdown of 30% to 50% (see

The anatomy of a failed breadth thrust). This scenario would imply the lower end of the range, with S&P 500 downside potential in the 2500 zone, which is about the bottom of the 2018 Christmas Eve panic bottom and the bottom of the 2020 COVID Crash.

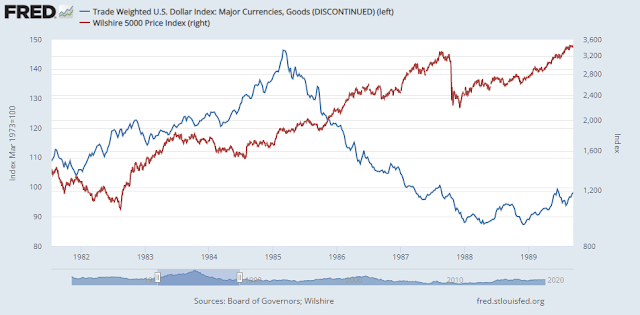

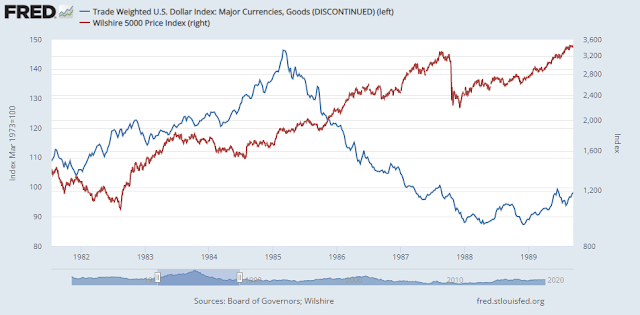

Despite the dire outlook, investors have to be aware of two potential bullish pivots on the horizon. The Fed’s hawkish policy is pushing up the value of the USD, which is wreaking havoc with other countries. Eventually, there will be sufficient pressure to weaken the greenback. At a minimum, a strong dollar weakens America’s terms of trade and becomes a headwind for US competitiveness, growth, and employment. The Plaza Accord experience is instructive for equity returns. Stock prices had been languishing for nearly two years until the Plaza Accord to weaken the USD and served as a catalyst for equity market strength.

The other possible pivot is a resolution of the Russo-Ukraine war, which would bring down energy prices. Such a development could be enormously bullish for operating margins as the price of energy inputs drop and serve to light a fire under the stock market. In light of the progress of Ukrainian forces on the battlefield, such an event may not be that farfetched or very far away.

In conclusion, there will be pain for investors. The combination of high energy prices and a determined hawkish Fed is equity bearish, but it may not be as bearish as the 1974 bear market. Investors have to be prepared for a sudden policy decision to weaken the USD, which would be bullish for stocks. As well, the possibility of an end to the Russo-Ukraine war could spark a rip-your-face-off stock market rally.

The 30-50% downside target seems realistic barring a forced pivot by the Fed. In the event of a pivot, while short term positive I wonder about the intermediate and longer term consequences if central banks are derailed from their inflation objectives. Even bigger issues down the road?

At the time of oil shock in 1973, the supply side was dominated by OPEC and energy was a much more significant part of the economy. Comparing a 2 million barrel cut in output (if it actually happens in full) to the oil shock is stretching it too far. Many more players now. Russia is supplying to India, China and African countries. That will not change. Europe is rethinking Nuclear and fracking. Gas shortages for the winter in Europe are likely to be minimal.

War in Ukraine and it’s effects are mostly priced in.

The key issue is inflation and the Fed Policy. Rightfully hawkish. The November and December hikes are well telegraphed and 2 year Treasury is almost at the target.

It’s the effects of rate hikes and QT that are harder to model. So many different outlooks out there – shows how difficult it is to price in.

I agree it’s best to be prudent and defensive. But forecasting targets in this environment is a loosing proposition.

Is the lack of liquidity the new risk?

The risks from derivatives have morphed

https://www.ft.com/content/917f8395-8fdd-4e8b-b3ae-b6e1c7872f60#comments-anchor

“Rising use of collateral creates liquidity risk. Sharp moves in prices result in large cash calls to meet current losses and higher initial margins due to increased volatility.”

Sure be open to the possibility of peace but its very, very unlikely. Zelensky just codified in law the principle of never negotiating with Putin. The war will continue for a while.

This potential S&P 2500 downside is reminiscent of what Ken had said some weeks ago…..