Preface: Explaining our market timing models

We maintain several market timing models, each with differing time horizons. The “Ultimate Market Timing Model” is a long-term market timing model based on the research outlined in our post, Building the ultimate market timing model. This model tends to generate only a handful of signals each decade.

The Trend Asset Allocation Model is an asset allocation model which applies trend following principles based on the inputs of global stock and commodity price. This model has a shorter time horizon and tends to turn over about 4-6 times a year. In essence, it seeks to answer the question, “Is the trend in the global economy expansion (bullish) or contraction (bearish)?”

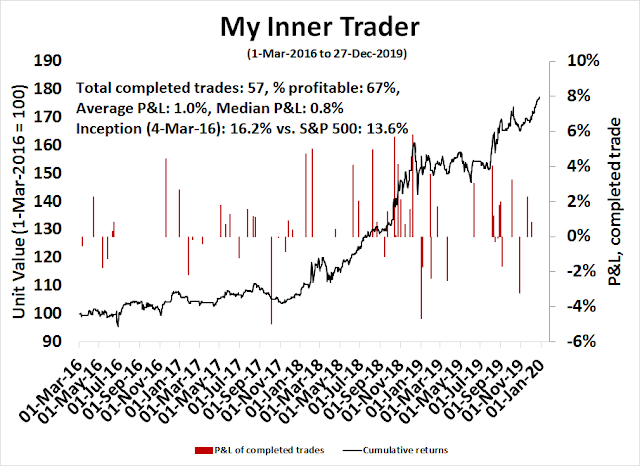

My inner trader uses a trading model, which is a blend of price momentum (is the Trend Model becoming more bullish, or bearish?) and overbought/oversold extremes (don’t buy if the trend is overbought, and vice versa). Subscribers receive real-time alerts of model changes, and a hypothetical trading record of the those email alerts are updated weekly here. The hypothetical trading record of the trading model of the real-time alerts that began in March 2016 is shown below.

The latest signals of each model are as follows:

- Ultimate market timing model: Buy equities

- Trend Model signal: Bullish

- Trading model: Bullish

Update schedule: I generally update model readings on my site on weekends and tweet mid-week observations at @humblestudent. Subscribers receive real-time alerts of trading model changes, and a hypothetical trading record of the those email alerts is shown here.

Is demographics really destiny?

‘Tis the season for strategists to publish their year-end forecasts for 2020. Instead of participating in that ritual, this is the second of a series of think pieces of what might lie ahead for the new decade (for the first see China, paper tiger).

It is said that demographics is destiny. Tom Lee at Fundstrat recently highlighted changes in spending and debt patterns. As the Baby Boomers age and fade into their golden years, the Millennial generation is entering its prime and they are poised to seize the baton of consumer spending, and eventually, political leadership.

Demographics is destiny holds true only inasmuch as people’s desires at different ages are roughly the same. But their desires are constrained by financial circumstances. The combination of a generational shift and differences in financial circumstances has profound implications for the political landscape, policy, and investing.

I believe that the coming decade is likely be the “OK Boomer” decade that sees a passing of the baton to the Millennial cohort characterized by:

- A greater focus on the effects of inequality

- A political shift to the left

- There are two policy effects that can be easily identified:

- The rise of MMT as a policy tool

- The rise of ESG investing

The question of whether these developments are good or bad is beyond my pay grade. However, investors should be prepared for these changes in the years to come.

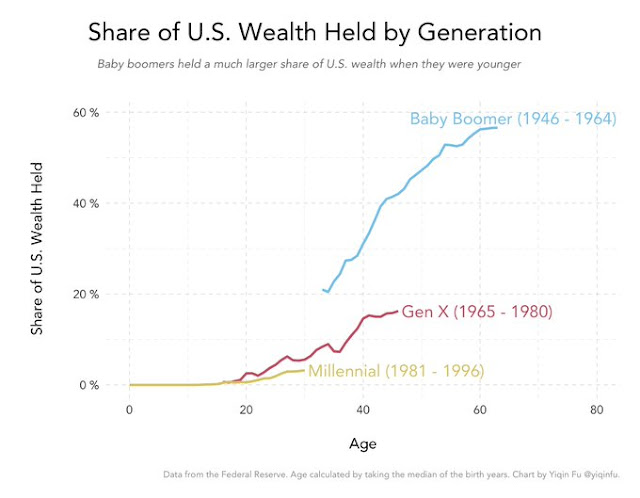

Addressing inequality

The biggest issue is inequality. While every generation thinks it had a hard time, inter-generational inequality is very real. Yiqin Fu, a political science Ph.D. candidate at Stanford, found that the wealth accumulation of each generation, Boomers, Gen X, and Millennial, at specific ages have diminished. In particular, the flatness of the Millennial line is astounding, and graphically illustrates the headwinds faced by the age cohort.

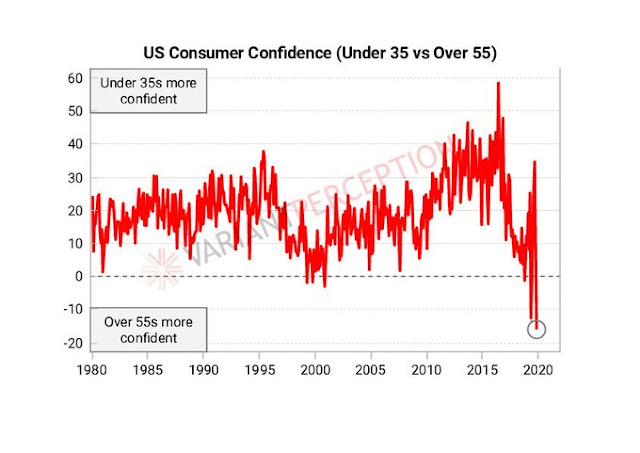

This inequality gap can be observed in many ways. Variant Perception pointed out that an enormous gulf in consumer confidence has opened up between the people under 35 compared to those over 55.

A Yahoo Finance article documented how Millennials simply cannot afford to buy a house:

Many millennial renters won’t be homeowners anytime soon – even if they want to be.

Among young adult renters who want to buy a home, 7 in 10 say they simply cannot afford one, according to a recent study by Apartment List, an online real estate company. The analysis was based on responses from over 10,000 millennial renters across America.

Renters said poor credit and the burden of future monthly mortgage payments were major obstacles. But the most commonly cited challenge was saving for a down payment, with 60% of young adult renters saying this is what has kept them from buying a home.

“Millennials today will need a 20% larger down payment than baby boomers,” said Dean Baker, chief economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research. “Housing prices are higher [even] when adjusted for inflation.”

A Bloomberg podcast with freelance writer Karen Ho explained the circumstances Millennials find themselves. Simply put, the Great Financial Crisis has scarred the cohort. Millennials began to enter the workforce just as the GFC cratered the global economy, and many were unable to get on the first rung of the ladder to wealth and financial stability. Instead, the economy restructured them out of promising entry-level jobs, leaving them only gig work with little stability, benefits, and pensions. Is it any wonder Millennials can’t afford to buy houses, or their wealth accumulation is so low compared to previous cohort?

A tilted playing field?

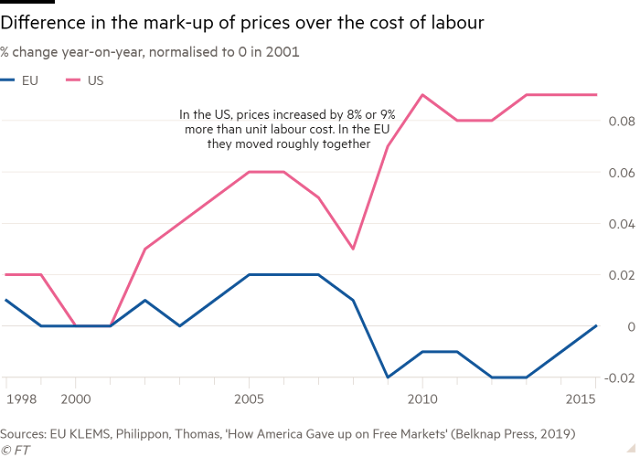

We are starting to see a radical re-think of economic assumptions and policy since the GFC. Martin Wolf recently reviewed a book by Thomas Philippon in the Financial Times that concluded that the US is no paragon of laissez-faire free market economics:

It began with a simple question: “Why on earth are US cell phone plans so expensive?” In pursuit of the answer, Thomas Philippon embarked on a detailed empirical analysis of how business actually operates in today’s America and finished up by overturning much of what almost everybody takes as read about the world’s biggest economy.

Over the past two decades, competition and competition policy have atrophied, with dire consequences, Philippon writes in this superbly argued and important book. America is no longer the home of the free-market economy, competition is not more fierce there than in Europe, its regulators are not more proactive and its new crop of superstar companies not radically different from their predecessors.

Competition policy has allowed large corporations to earn monopolistic or oligopolistic profits:

[Philippon] crisply summarises the results: “First, US markets have become less competitive: concentration is high in many industries, leaders are entrenched, and their profit rates are excessive. Second, this lack of competition has hurt US consumers and workers: it has led to higher prices, lower investment and lower productivity growth. Third, and contrary to common wisdom, the main explanation is political, not technological: I have traced the decrease in competition to increasing barriers to entry and weak antitrust enforcement, sustained by heavy lobbying and campaign contributions.”

All this is backed up by persuasive evidence. Those prices of broadband access in the US are, for example, roughly double what they are in comparable countries. Profits per passenger for airlines are also far higher in the US than in the EU.

The analysis demonstrates, more broadly, that “market shares have become more concentrated and more persistent, and profits have increased.” Moreover, across industries, more concentration leads to higher profits. Overall, the effect is large: the post-tax profit share in US gross domestic product has almost doubled since the 1990s.

Brad Setser at the Council on Foreign Relations described the US external position as “A Big Borrower and a Giant Corporate Tax Dodge”.

The argument that the United States functions as a financial intermediary that borrows cheaply to buy higher yielding financial assets—e.g. a skilled user of leverage—has a long intellectual history. And it naturally has a certain amount of appeal to many American financiers. It dates back to the original French critique of the exorbitant privilege the Bretton Woods system accorded the United States. Under the (brief) gold-dollar standard, the rest of the world was more or less required to build up dollar reserves—providing an inflow to the United States. And back in the 1960s, the U.S. current account was in balance, so the United States was using the inflows to fund riskier and higher yielding investment abroad. France was complaining that it was funding the takeover of Europe by U.S. multinationals…

The belief that the US uses its position to buy higher returning assets while issuing debt is no longer true. Setser found that the excess return on foreign investment is largely attributable to tax arbitrage, or a favorable tax treatment of offshore corporate profits embedded in the US tax code.

The excess return is entirely a function of the large profits U.S. firms book in the world’s corporate tax havens—the U.S. surplus stems from the large returns the United States appears to earn on its investments in Ireland, the Netherlands, and Bermuda. Basically, it looks to be a function of the United States’ willingness to tolerate a world where American tech and pharma companies’ offshore earnings aren’t really taxed by the United States at anything like the rate onshore profits are taxed at. Previously those profits were tax deferred, now they are largely taxed at the low GILTI rate of 10.5 percent.

In short, US policy has tilted the playing field in favor of large corporations, and this has exacerbated inequality.

Future policy implications

There are signs that the Overton window, or the ideas that define the spectrum of acceptable discussion, is changing on inequality policy.

Even the Fed is becoming more concerned. In an economic environment where the labor market is viewed as tight, economists in a more traditional framework would normally be concerned about the low unemployment rate causing inflationary pressures. Instead, Jerome Powell made a speech on November 25, 2019 which devoted four paragraphs to “spreading the benefits of employment”. First, he acknowledged the tight labor market has begun to benefit “low and middle income communities”:

Many people at our Fed Listens events have told us that this long expansion is now benefiting low- and middle-income communities to a degree that has not been felt for many years. We have heard about companies, communities, and schools working together to help employees build skills—and of employers working creatively to structure jobs so that employees can do their jobs while coping with the demands of family and life beyond the workplace. We have heard that many people who in the past struggled to stay in the workforce are now working and adding new and better chapters to their lives. These stories show clearly in the job market data. Employment gains have been broad based across all racial and ethnic groups and all levels of educational attainment as well as among people with disabilities.

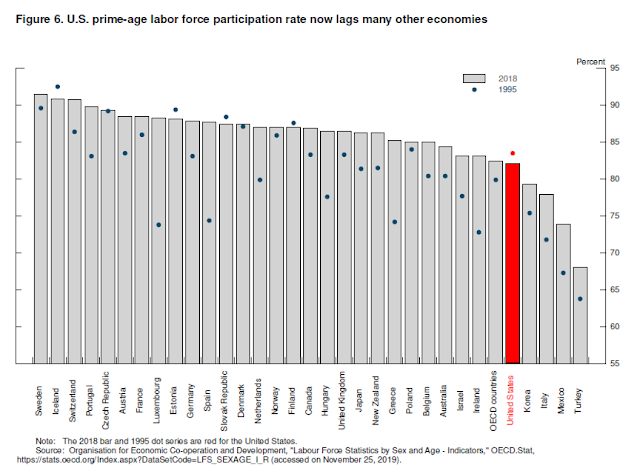

He further gave a nod to Millennials by observing that the US prime age labor force participation rate had fallen behind other major industrialized countries in 2018 compared to 1995.

In a surprising “the dog that did not bark” manner, Powell did not sound like a conventional economist and raise the risks of rising inflationary pressure from low unemployment.

Recent years’ data paint a hopeful picture of more people in their prime years in the workforce and wages rising for low- and middle-income workers. But as the people at our Fed Listens events emphasized, this is just a start: There is still plenty of room for building on these gains. The Fed can play a role in this effort by steadfastly pursuing our goals of maximum employment and price stability. The research literature suggests a variety of policies, beyond the scope of monetary policy, that could spur further progress by better preparing people to meet the challenges of technological innovation and global competition and by supporting and rewarding labor force participation. These policies could bring immense benefits both to the lives of workers and families directly affected and to the strength of the economy overall. Of course, the task of evaluating the costs and benefits of these policies falls to our elected representatives.

Is the Phillips Curve dead? Not yet, but it seems to be in the ambulance and policy makers are trying to revive it using extraordinary means by redefining u*, or the natural rate of unemployment. Here is what Powell said at the December FOMC press conference: “It’s already understood, I think, that even though we’re at 3.5% unemployment, there’s more slack out there, in a sense. The risks to using accommodative monetary policy…to explore that are relatively low.”

The Fed is conducting a review of its policy approach, and the review will not be complete until June 2020. Until then, the Phillips Curve remains part of the Fed’s monetary policy framework.

Fed watcher Tim Duy also noticed a shift towards a focus on inequality:

Persistently excessive unemployment has its costs. Not only does the period of low unemployment not extend long enough to spread its benefits to the most challenged sections of the labor market, but it also tips the scales toward employers when it comes to wage bargaining. Workers who are always fearful of losing their jobs have little incentive to derive a hard bargain for higher wages.

Boesler credits Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari with leading the charge on this issue, arguing that the Fed policy does have a role in distribution outcomes. And he is not wrong; indeed, Kashkari tendency toward dovishness has proven more correct than not since he came on board. His concerns about inequality helped prompt him to launch the Minneapolis Fed’s Opportunity and Inclusive Growth Institute and has now found its new leader in the highly-respected economist Abigail Wozniak.

The implication for policy of a broad acceptance of idea that the Fed may have contributed to inequality in the past is that the Fed is likely to be much more cautious when raising rates and respond to economic weakness much more quickly. In other words, this adds another reason to expect rates will remain lower than what we might have thought the Fed’s reaction function would suggest.

The Overton window for economic policy is indeed shifting. Bloomberg reported that the latest Nobel laureate Abhijit Banerjee is arguing for raising taxes for redistribution as a way to spur economic growth:

How do you spur demand in an economy? By raising taxes, not cutting them, says this year’s winner of the Nobel prize for economics.

Reducing taxes to boost investment is a myth spread by businesses, says Abhijit Banerjee, who won the prize along with Esther Duflo of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Michael Kremer of Harvard University for their approach to alleviating global poverty. “You are giving incentives to the rich who are already sitting on tons of cash.”

A better approach would be to raise some taxes and distribute the money to people to spend, Banerjee said in an interview Monday in New Delhi, where he was promoting his book ‘Good Economics for Hard Times.’“You don’t boost growth by cutting taxes, you do that by giving money to people,” he said. “Investment will respond to demand.”

Move over, Reagan style laissez-faire economics. Elizabeth Warren style redistribution is taking over.

A leftward political shift

It is said that science advances, one funeral at a time, meaning that as the old guard dies off, new ideas take their place. As the demographic profile of the American population changes, the same is likely to happen with political discourse.

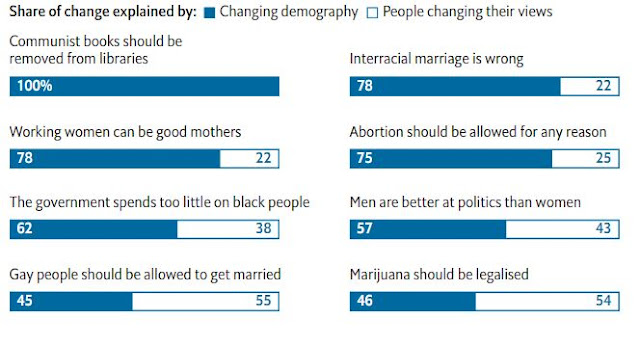

The Economist documented that people don’t often change their minds, but societies do because of demographic changes.

Since 1972 the University of Chicago has run a General Social Survey every year or two, which asks Americans their views on a wide range of topics. Over time, public opinion has grown more liberal. But this is mostly the result of generational replacement, not of changes of heart.

For example, in 1972, 42% of Americans said communist books should be banned from public libraries. Views varied widely by age: 55% of people born before 1928 (who were 45 or older at the time) supported a ban, compared with 37% of people aged 27-44 and just 25% of those 26 or younger. Today, only a quarter of Americans favour this policy. However, within each of these birth cohorts, views today are almost identical to those from 47 years ago. The change was caused entirely by the share of respondents born before 1928 falling from 49% to nil, and that of millennials—who were not born until at least 1981, and staunchly oppose such a ban—rising from zero to 36%.

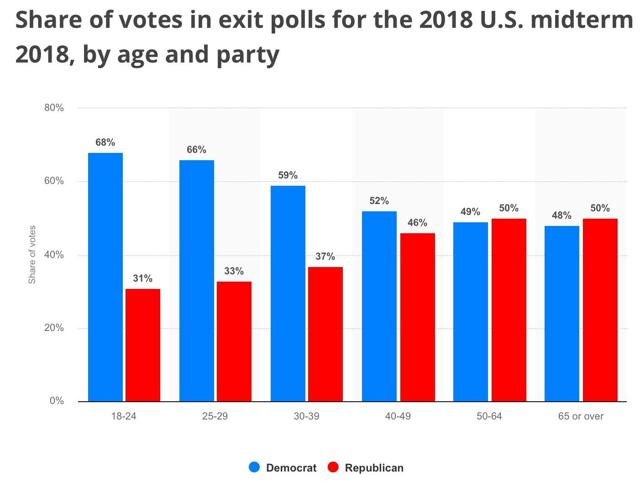

The Millennial Young Turks are far more left leaning than older cohorts. Gallup also found that Millennials and Gen Z are far more favorably disposed to socialism than older generations.

The age demographic profile of the US 2018 midterm elections also tell a similar story of a shift in the political pendulum. Expect the Democrats to gain ground over the Republicans in the coming decade.

Another article in The Economist explained that Millennial socialism boils down to three big ideas, namely more government, a “Green New Deal”, and capitalism robs people of dignity and freedom.

According to the millennial socialists, more radical changes are required. Collectively, their manifesto boils down to three big ideas. First, they want vastly more government spending to provide, among other things, free universal health care, a much more generous social safety-net and a “Green New Deal” to slash carbon-dioxide emissions. Second, many argue for looser monetary policy, to reduce the cost of funding these plans.

The third plank of their thinking is the most radical. The underlying idea is that capitalism does not just produce poverty and inequality (though it does), but that, by forcing people to compete with each other, it also robs them of dignity and freedom. “The power imbalances are obvious when you enter into your employment contract,” says Mr Sunkara. For Mr Adler, capitalism “has sucked the life out of democracy”.

Millennial socialists, therefore, support the “democratisation” of the economy (or socialisme participatif, as Mr Piketty puts it), whereby ordinary people play a greater role in the production process, the market is removed from as many aspects of everyday life as possible, and the influence of the rich is drastically curtailed. Such reforms, they argue, will create happier and more empowered citizens.

These big political shifts have broad investment implications.

Expect rising inflationary expectations

The first is the ascendancy of the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) as an economic paradigm. For the uninitiated, MMT states that a government that issues debt in its own currency is only constrained by the willingness and ability of the bond market to fund its debt. Japan is a prime example. Austrian economic orthodoxy would have called for a collapse of the Japanese economy from the immense debt burden, but the short JGB trade has been a widowmaker for traders for decades.

Michael Pettis set out some policy guidelines of what he called “MMT Heaven and Hell”.

MMT isn’t just about printing money, but what happens after the government prints money and the mechanisms that cause inflation. The government could print money by giving it to the rich. If the economy is capacity constrained, and the rich spend the money on productive investments, the stimulus is “MMT heaven”, or non-inflationary growth. If the government prints money to give to the poor, and the economy suffers from too little demand, then the funds in the hands of the poor spurs non-inflationary growth. A third alternative is for the government to print money and spend it on productive infrastructure, which has the same economic effect as giving money to the rich in a capacity constrained economy.

In other words, MMT adoption does not always lead to inflation. Christine Harper, the co-author of Paul Volcker’s memoir, revealed in a Bloomberg article that Volcker the Great Slayer of Inflation was surprisingly agnostic about MMT:

Another time, I asked for his view of Modern Monetary Theory, which posits that a government with its own central bank and currency can and should keep spending until the economy is running at full employment. Surely the greatest living inflation fighter would recoil at such a prospect? But instead he simply pointed out that MMT hadn’t really been tested.

For investors, this means that inflationary expectations are likely to rise, though the jury is still out on whether any implementation of MMT is necessarily inflationary. Bonds have been in a secular bull market since Volcker began to squeeze inflationary expectations out of the system around 1980. As bond yields have fallen, so has bond portfolio duration, or the price sensitivity of bonds to interest rate changes. At a minimum, expect greater price volatility from bonds.

The dawn of ESG investing

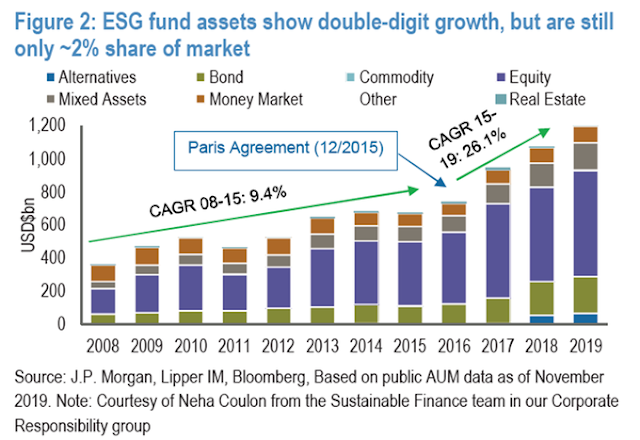

Another trend to expect in the coming decade is the rise of ESG (environmental, social, and governance principled) investing. Time magazine’s designation of Greta Thunberg as “person of the year” is a signal that ESG principles are inexorably on the rise.

John Authers also recounted how ESG investing has invaded the hallowed halls of Harvard and Yale, and why that’s important:

If you want to see the future of climate-based investing, you need to look at Harvard and Yale. For those tired of debates dominated by elite universities, note that I am not talking about what goes on inside those hallowed halls…Students from the two universities’ campaigns to divest from fossil fuels (Yale Endowment Justice Coalition and Divest Harvard), staged a joint invasion of the field. Both want their endowments (the two largest university nest eggs on the planet) to get rid of all exposure to oil, coal and gas. They also called for divesting from holdings in Puerto Rican debt.

This is important because university divestment campaigns have a history of working. In the 1980s, when the apartheid regime in South Africa was the target, such campaigns contributed to the pressure on the country that eventually led to the release of Nelson Mandela and black majority rule. Universities tend to be averse to negative publicity, while trustees of their endowments tend to prefer the quiet life.

Authers also highlighted an InfluenceMap report of how major funds are deviating from climate investing.

Their analysis found that the world’s 15 largest investment institutions, which have $37 trillion in assets under management between them, are collectively deviating from the “Paris-aligned” allocations needed to reach the Paris Agreement goal of stopping global temperatures rising by 2 degrees. Doing this primarily requires divestment from automakers, while making big investments in alternative energy producers. World markets as a whole deviate by 18%; the big institutions deviate by 15% to 21%.

Jeroen Blokland observed that ESG just forms 2% of the overall market, indicating enormous scope for growth. The initial shift will likely begin in Europe, as a political consensus is forming that climate change is an emergency. By contrast, the climate change threat remains a subject of debate in the US.

It is easier to identify the losers than the winners under ESG. ESG standards are still in their infancy and are evolving. Different providers are producing highly different results. However, we can definitively say that carbon emitting energy sectors are going to be the losers, such as energy giant Saudi Aramco, which staged an IPO into an unfortunate headwind.

To be sure, the poor relative returns to the oil and gas industry over the last five years has put a brake on capital investment, and the under-investment will be reflected in supply constraints in the near future that is likely to boost energy prices. While energy prices may rise, the coincidental rise in ESG investing may also serve to restrain the returns of oil and gas equities and fixed income instruments. That’s the idea behind ESG, raise the cost of capital sufficiently to discourage further investment in carbon spewing projects.

In conclusion, the coming decade is likely be the “OK Boomer” decade that sees a passing of the baton to the Millennial cohort characterized by:

- A greater focus on the effects of inequality

- A political shift to the left

- There are two policy effects that can be easily identified:

- The rise of MMT as a policy tool

- The rise of ESG investing

The question of whether these developments are good or bad is beyond my pay grade. However, investors should be prepared for these changes in the years to come.

The week ahead

I am still on holiday this week and I am writing this on a laptop with an uncertain internet connection, so this comment will be somewhat brief.

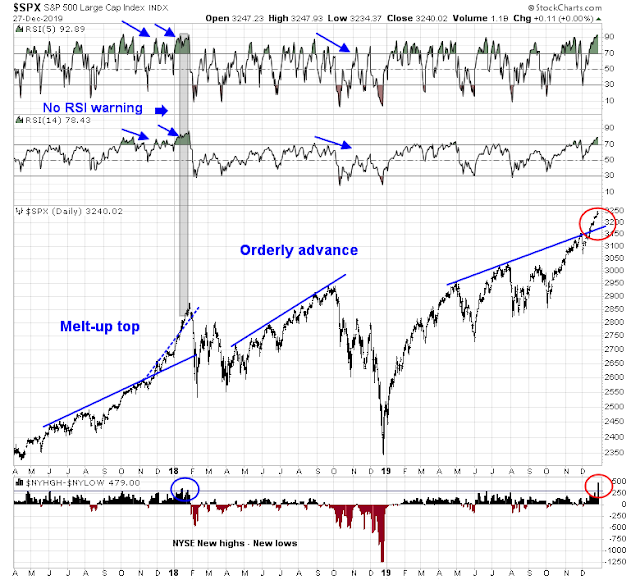

Just before I left, I rhetorically asked if the market was melting up (see Is the market melting up?) as there were both pros and cons to the melt-up case at the time. We now have the answer. This is a market blow-off, which will inevitably be followed by a correction in the manner of early 2018.

I had outlined a number of metrics to tell if this is a market melt-up. SentimenTrader analysis of Google searches and Bloomberg stories shows that current readings exceed the late 2017 and early 2018 experience. Sentiment is supportive of the melt-up scenario.

Does this mean that the stock market is ready to peak? Not necessarily. SentimenTrader also observed that Trump’s market tweets have not exceeded the early 2018 count. So the jury is still out.

Most sentiment indicators are flashing wildly crowded long levels, but that is to be expected in a blow-off top. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean that prices will retreat right away. As an example, the Fear and Greed Index closed Friday at an astounding 92 reading, but history shows that sentiment indicators tend to be better trading signals at bottoms, rather than tops.

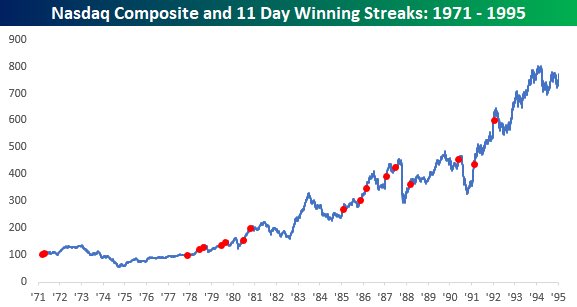

For some perspective, the NASDAQ Composite sported a rare 11-day winning streak. Analysis from Bespoke (via Liz Ann Sonders) found that such instances have historically not resolved in a bearish manner.

The table of future returns after such episodes have been dominated by continued price momentum, which saw above average returns for all time horizons.

Both my inner investor and trader are bullishly positioned. Trading volume is expected to be light early in the week, but the possibility of further fast money FOMO chase still exists. My inner trader is keeping a close eye on his trailing stops in this high risk/high reward environment.

I expect to back at my desk mid-week. Stay tuned.

Disclosure: Long SPXL

Boomers did not spend with Starbucks, did not have mobile phones or tablets did not think a lot of brands – David Bowie united many – like listening to him. Boomers worked and strangely saved. Boomers had good holidays – eventually. Today the young have access to all and find housing difficult to pay for. Perhaps they are just thick.

“Abhijit Banerjee is arguing for raising taxes for redistribution”

If the above idea were to be true, what incentive would there be for wealthy to produce wealth by TAKING RISK, if the eventual outcome would be loss of such wealth to taxation (for redistribution)?

To be sure, perhaps capitalism has gone too right wing, and demographic shifts may tilt back to a more liberal slant (call it socialism if you may), as demographics shift based on your missive above.

That said, the rise of conservatives in recent elections (UK 2019, Australia 2019, India 2019, USA 2016), is opposite of the liberal tilt, redistribution of wealth, socialism being talked about in this article. The massive and decisive conservative mandate in the UK in recent elections may be a tell of liberal ideology being soundly defeated. Hillary Clinton’s loss, and Elizabeth Warren’s alarm bells of low fund raising all point towards a more conservative right wing ideology gaining ground. Sorry, I do not want to make this into a political argument, much as though that is what it sounds from what I am writing.

MMT: Wasn’t Weimar republic based on MMT?

Successful Investing in a Moonless World

Including, why stock markets will surprise the gloomy experts and do great.

Moonless World Definition:

We had a Mooned World before the GFC and it has been Moonless since. The Moon is the Central Banks that regulate interest rates and therefore the stock market and economic cycles. Before the GFC, the Moon would cause large tides of interest cycles that would cause synchronized boom-bust waves in stock markets and the economy. After the GFC, Central Bankers, the Moon, have been too worried about the fragility of their economies to shift from easing. This is a Moonless World.

Current Environment – Moonless World Confirmed:

In 2018, there was one last attempt to return to pre-GFC Central Bank policies. Jerome Powell, when confirmed as Chairman of the Fed, sought to bring interest rates and the Fed balance sheet to ‘normal’ levels. That was abandoned in 2019 after stock markets fell and yield spreads started to blow out. Before the GFC, this was all normal cyclical stuff. A short recession would be allowed to happen to cleanse the system of overconfidence that breed excesses, in the current case, large corporate borrowing.

First, the Fed made a major interest rate policy shift and then in September an equally major balance sheet policy shift (QE4) even though the economy and unemployment were fine. A try for ‘normal’ will never be attempted again. The excesses of corporate borrowing will continue growing and certain to become too systemically dangerous to harness. The opportunity to stop the general borrowing craziness was missed. Rolling defaults of overleveraged players will happen in future but not simultaneously enough to cause a crash. This is a benefit of a Moonless World.

This means we are now in an interest rate environment of ‘lower forever’ not just ‘lower for longer.’ Also, risk premia for stocks and corporate debt will fall now that it’s been confirmed that a broadly synchronized recession will not be allowed to happen.

Investors are puzzled as to why there has been no bear market since 2009. In a Moonless World, this is the norm. If there ever is a bear market, Central Bankers will not be the cause.

Investment Implications-Corporate Bonds:

In a Moonless World, we do not have synchronized booms and busts. This is a profound dynamic that has been evident for the last decade. Industries go through their own boom/bust cycles. For example, the energy industry went from its boom in 2014 to 2016 bust due to its fracking technology disruption causing oil prices to plunge. The established retail industry is being disrupted by technology as well with internet retailers not by Moon instigated business cycles. The Steel and Agriculture industries are impacted by political policies.

Industries have to be analyzed individually without concern for a general economic recession.

For example, in 2007 and early 2008, the Fed raised interest rates to cool the overheated real estate sector. That caused an economy wide recession encompassing all industries with massive corporate bond defaults and personal bankruptcies. High yield indexes saw twenty percent or more default rates. Bearish corporate bond investors point to the current large spreads over current default rates, scoff and say we will see a surge in defaults in the next recession that will bring investors to tears. They say current excess yields will be more than given back. But no, in a Moonless World, there will never be synchronized recessions so these worries are overblown.

The current high yield market is proof of market players adapting to a Moonless World. In 2015, high yield spreads blew out as oil prices plunged and bankruptcies spread in the energy industry. Negative sentiment caused spreads to widen in other industries in sympathy as traders remembered previous recessions. But when the defaults didn’t spread, traders realized we were in a new world. Over the last year, the energy industry is again stressed but this is affecting spreads in other industries much less if at all. Investors are analyzing individual companies on their own and their industries’ fundamentals.

In a Moonless World, we will see some unsuccessful companies default occasionally or an industry become stressed but there won’t be a synchronized recession. Therefore, risk premia for corporate debt should fall significantly.

Investment Implications-Stocks:

In early 2016, Warren Buffett said that stocks would be a bargain at that time ‘if only interest rates would stay low.’ He didn’t think that would happen but thought it worth mentioning. At that time for the first time in decades, dividend yields of the market were higher than longer-term bond yields. So relative valuation made stocks a bargain versus bonds even though the stock market had gone up for seven years. Nobody really believed that rates would stay low forever but there were many investors taking up the cry of “lower for longer’. Stock markets made an important low at that point in early 2016 and went on an almost three-year bull market. Stocks didn’t have a major hiccup until Mr. Paulson tried for ‘normal.’ He tried to have the Moon re-orbit just like the old days. But he gave up.

We are now in a Moonless World forever. Forget ‘lower for longer’, embrace ‘lower forever.’

Stocks yield more than bonds again. They are a huge bargain in this Moonless world. Value Factor stocks are an absolute steal. Here are some stats from ETF Research Center:

Value Factor ETF VLUE, 2020 PE 10.7X or 9.3% Earnings Yield, Dividend Yield = 2.9%, compounded dividend growth rate = 6.7%

Summary

In a ‘lower forever’ world without synchronized recessions the 148 companies in this ETF will generally do fine. Individual companies and individual industries will be disrupted or have their particular recessions but the key is that these will not be synchronized disasters. Risk premia for Value Factor companies in a Moonless World is much lower now. This makes the Value Factor extremely cheap.

Quality Factor ETF SPHQ, 2020 PE 18.6X or 5.4% Earnings Yield, Dividend Yield = 2%, compounded dividend growth rate = 9.1%

The 100 great companies in this ETF are already thriving in this swiftly changing political and digitally disrupted business world. In a Moonless World of ‘lower forever’ interest rates, this group of great companies is great value.

S&P 500 ETF SPY, 2020 PE 17.7X or 5.6% Earning Yield, Dividend Yield = 2.0%, compounded dividend growth rate = 7.5%

Summary

The overall stock market is excellent value after September’s Fed capitulation confirming a Moonless World of ‘lower forever’ interest rates.

Equities – Comparing the Statistics

Today we have the 10 year Treasury yielding 1.9% with the three ETFs above having earnings yields of 5,4%, 5,6% and 9.3%. Their dividend yields are at 2.9%, 2.0% and 2.0% which is higher than the Treasury yield plus the yields have grown at 6.7%, 9.1% and 7.5% rates and will very likely grow in future.

Now that we are in a confirmed Moonless World of ‘lower forever’ interest rates, stock have become extreme bargains and will do surprisingly well in 2020 and beyond. Previously successful money managers and strategists who do not accept the implications of a permanently Moonless World will be confused, overly cautious and continually call for the imminent collapse of an expensive stock market on historical metrics that no longer apply.

Likewise, market strategists will correctly observe that corporate and sovereign debt will be growing to systemically dangerous levels that will cause a crash at the next recession. But Fed officials also see this and will therefore never cause a simultaneous economic downturn by raising interest rates meaningfully. Obvious problems are avoided.

We are in a Moonless World with tide levels of interest rates extremely tame – forever.

Back in early 2016 when I turned bullish when most strategists (not Cam) were saying the markets were due for a bear after going up seven years, my company strategist was consistently negative. I kept emailing him saying, “If you diss it, you’ll miss it.”

After the Fed’s September confirmation of giving up on withstraining the growth of excessive corporate debt, I say to anybody who stays negative in the next few years, “If you diss it, you’ll miss it.”

The above is not investment advice for any individual. I don’t know your circumstances or risk tolerance. It’s a long-term overview of the next several years and meaningful drawdowns may occur at any time. Cam is excellent is spotting those which is why I’m a loyal subscriber.

Thanks Ken for your timely and insightful posts. Happy new year.

“Move over, Reagan style laissez-faire economics. Elizabeth Warren style redistribution is taking over.”

It seems every generation has to learn the lessons all over again through trial and error. Somehow I feel that this time they might fail.

Happy new year, Cam.

Hey Cam,

The early 2018 top was an extreme overgought condition – 14 month RSI around 85 and 14 week RSI ~90 for SPX… Both are around 70 now. The current overbought condition is only apparent on daily charts and should be worked off easily by much smaller pullbacks.

If you are suggesting similar end, are you expecting much higher prices first?

Btw, I thought you were going to skip this weekend because of the vacation. Thanks for your hard work!

Comment on the ESG stuff:

I think we are already seeing some of that being played out. An example would be renewable energy comps “making it” on govt subsidies and mandates.

Sometime ago their break-even price was below zero!

The current melt-up scenario seems tame compared to the late Nineties – how effective are sentiment indicators when the chase is on and no one wants out?

I used to follow Herb Greenberg when he was a columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle. At one point in the Nineties he recommended shorting Dell – and continued to confidently press his point as the stock price rose unabated. To his credit, he published his decision the day he capitulated.

Are we in fact overdue for a correction? What if global indexes climb another +15% before correcting -8%? Trading isn’t easy – there’s always someone on the other side of any bet, and I always assume he/she may be a lot smarter than I am.

Are CLOs backed by corporate debt a systemic threat, ala 2008?

https://www.wsj.com/articles/financial-watchdog-warns-about-dangers-of-leveraged-loans-11576749600?mod=article_inline

https://www.wsj.com/articles/fed-flags-elevated-asset-prices-high-debt-as-u-s-financial-risks-11573844938?mod=article_inline

One warning is from the FSB (Financial Stability Board), the other from the US Federal Reserve.

Ken & Cam: Nice posts & Happy New Year to All