Preface: Explaining our market timing models

We maintain several market timing models, each with differing time horizons. The “Ultimate Market Timing Model” is a long-term market timing model based on the research outlined in our post, Building the ultimate market timing model. This model tends to generate only a handful of signals each decade.

The Trend Model is an asset allocation model which applies trend following principles based on the inputs of global stock and commodity price. This model has a shorter time horizon and tends to turn over about 4-6 times a year. In essence, it seeks to answer the question, “Is the trend in the global economy expansion (bullish) or contraction (bearish)?”

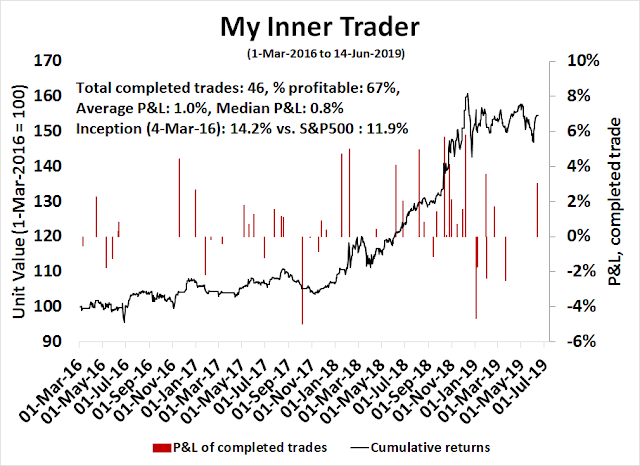

My inner trader uses a trading model, which is a blend of price momentum (is the Trend Model becoming more bullish, or bearish?) and overbought/oversold extremes (don’t buy if the trend is overbought, and vice versa). Subscribers receive real-time alerts of model changes, and a hypothetical trading record of the those email alerts are updated weekly here. The hypothetical trading record of the trading model of the real-time alerts that began in March 2016 is shown below.

The latest signals of each model are as follows:

- Ultimate market timing model: Buy equities

- Trend Model signal: Neutral

- Trading model: Neutral

Update schedule: I generally update model readings on my site on weekends and tweet mid-week observations at @humblestudent. Subscribers receive real-time alerts of trading model changes, and a hypothetical trading record of the those email alerts is shown here.

An FOMC meeting preview

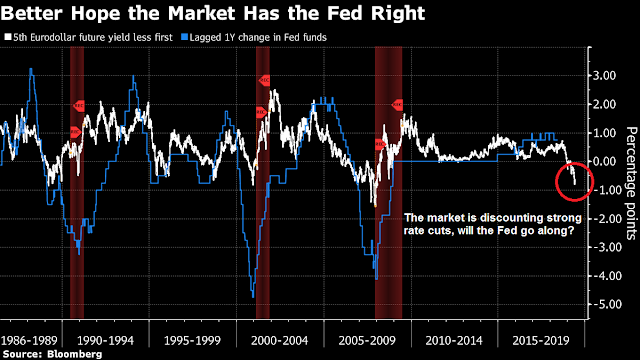

As we look ahead to the FOMC meeting next week, the market has priced in three quarter-point rate cuts for 2019, with the first cut occurring at the July meeting.

A rate cut is not unexpected, as the bond market has pushed the Treasury yield curve down so far that only the 30-year Treasury bond is trading above the current Fed Funds target. It is likely too early for the Fed to cut rates at its June meeting next week, but if the market is discounting a July cut, the Fed is likely to signal either it is either in agreement with that expectation, or correct the market.

Rather than debate whether the Fed should cut rates, I consider the scenario of what might happen if it were to proceed with a July rate cut. What are the consequences for economic growth, and the stock market? After all, the track record of Fed Funds futures in forecasting the actual trajectory of interest rates has been less than stellar.

I conclude that while the Fed could decide to cut rates at its July FOMC meeting, the future path of interest rates and stock prices depends on the reasoning behind the rate cut. If the cut is in response to the eruption of a full-blown trade and economic cold war with China, then it is likely to be the start of a protracted rate cut cycle, with bearish implications for equity prices. On the other hand, if the rate cut is an “insurance” cut designed to head off further economic weakness in the face of a stalemated trade dispute, I expect the cut to be reversed relatively quickly because the global growth backdrop remains constructive. Equity prices would rise under such a scenario as the bullish implications of higher growth would overwhelm the bearish implications of higher interest rates.

1995 all over again?

Fed watcher Tim Duy believes that the soft May Jobs Report is clearing the way for a rate cut. He believes that the Fed may be trying to engineer a 1995-style soft landing.

The current setup feels a lot like 1995.Then, like now, the Fed spent the first part of the year struggling with the magnitude of the economic slowdown underway. By the time of the July 1995 meeting, however, the Fed had enough evidence in hand to justify a rate cut, the first of three 25 basis point cuts. Interestingly, the employment picture shifted in the first half of 1995 as it has so far in the first half of 2019. If the Fed can engineer a repeat, 1995 would be a good model to follow as it is arguably the only instance of a soft landing for monetary policy.

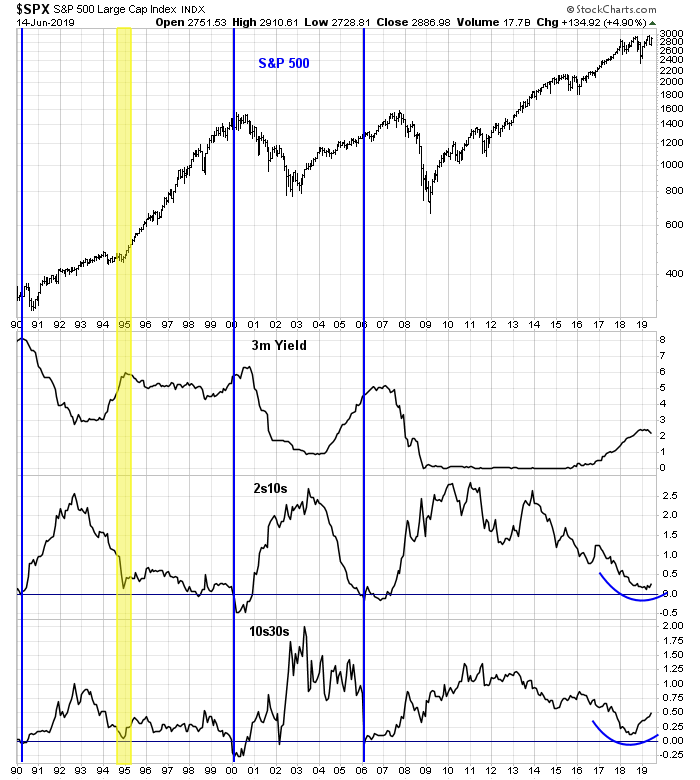

As a reminder, here is how interest rates, stock prices, and the yield curves behaved since 1990. The yield curve, as measured by the 2s10s and 10s30s, were on the verge of inverting when the Fed stepped in and began to ease policy. Stock prices consequently took off, and the run did not end until the NASDAQ Bubble burst in 2000. By contrast, the vertical lines depict the instances when the 2s10s and 10s30s both inverted, and the stock prices topped out soon afterwards. The key difference today is while the 3-month yield is above the 10-year, the 2s10s and 10s30s are nowhere near inversion.

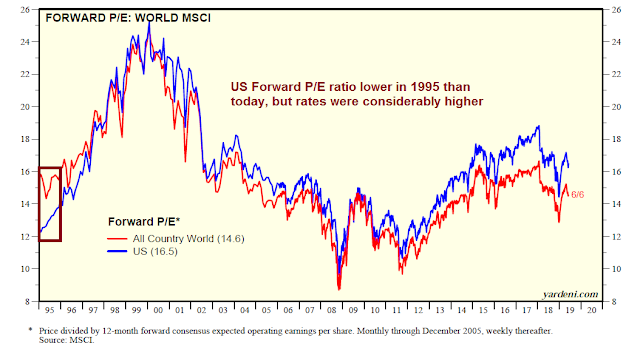

The subsequent rise in equity prices was not surprising, but it cannot be said that the rally was purely valuation driven. Data from Yardeni Research Inc. shows that US forward P/E ratios were lower than they are today, but both short and long rates were considerably higher in 1995 than they are today. By contrast, global forward P/E ratios are roughly the same level they were in 1995.

Gavyn Davies, writing in the Financial Times, agrees with the 1995 analogy. In particular, Davies pointed to the CNBC interview with Fed vice chair Richard Clarida as evidence for a precautionary rate cut:

Fed vice-chair Richard Clarida explained in a must-read CNBC interview that he “as one member of the committee” would tend to look through the initial effects of higher tariffs on the price level, while seeking to ensure that the economy continued to grow at or near trend.

This clearly suggests that any slowdown in the growth rate, which is already slightly below trend, will trigger a policy easing, even if tariffs are pushing 12-month consumer price increases upwards at the time.

Mr Clarida went further when he pointed out that policy had been eased in the past (he specifically mentioned 1988 and, significantly, 1995) in order to provide an insurance against downside risks to activity. He added that the need for a pre-emptive easing this year would be assessed as new evidence presents itself.

It is interesting that the vice-chair, an accomplished economist who is increasingly vocal as a policy spokesman, seems ready to ignore the possible inflationary effects of the president’s programme of tariff increases. These effects were initially expected to be small and manageable, but recently estimates have increased substantially.

Davies concluded:

There is little doubt that the doves on the FOMC, including Mr Clarida and Charles Evans, are moving towards a 1995-style “insurance” cut in policy rates. Then, the Greenspan Fed cut rates by 75bp over an eight-month period, arguing that these cuts were justified by success in bringing inflation under control, at a time when downside risks to economic activity appeared to be on the increase. An economic soft landing followed.

Mr Powell is likely to reflect this thinking in his press conference after the next policy meeting on June 19. The committee will probably not implement a rate cut on that date, because of its earlier promise to be “patient”. But it might use the interest rate “dot” plot to foreshadow one or more rate cuts before year end.

In addition, rate cuts can further be justified in the face of tame inflationary expectations (via the Cleveland Fed).

Scenarios for a July rate cut

Supposing that the Fed were to signal that it is open to a July rate cut next week. What does that mean? While current economic conditions are a little soft, the case for rate cuts is a little unclear. The wildcard that presents downside tail-risk is a trade war.

For some perspective on the near and longer term outlooks, I refer you to the work of New Deal democrat, who monitors high frequency economic indicators and helpfully categorizes them into coincident, short-leading and long-leading indicators. He is sounding nervous about the short-term outlook, which has turned negative, in light of trade war uncertainties.

Between lower interest rates and improving real money supply, the overall long-term forecast has turned even more positive. The short-term forecast, however, remains negative, and the nowcast has declined from weakly positive to neutral.

As I have pointed out before, these metrics are good at forecasting the economy “if left to its own devices.” At present, however, it’s far from being left to its own devices, in particular because of chaotic trade and tariff policies. Even if one agrees with the trade objectives and the use of tariffs toward those objectives, however, the chaotic nature of their deployment is asymmetrically negative, as no one can be sure that even a fully agreed to trade deal can survive beyond the next tweet. Thus the near-term forecast is not better than, and may well be worse than, indicated by these indicators.

There are many obstacles to a deal. The current state of the US-China trade dispute cannot be resolved by low-level negotiators, and the big issues have to be resolved by the respective presidents. The American side has announced that Trump and Xi will meet to discuss trade at the G20 meeting in Japan in late June. However, the Chinese side has not confirmed the meeting. Bloomberg reported that Trump’s threats of imposing tariffs if there is no trade meeting at the G20 have painted Xi into a corner:

Trump on Monday said he could impose tariffs “much higher than 25%” on $300 billion in Chinese goods if Xi doesn’t meet him at the upcoming Group of 20 summit in Japan. China’s foreign ministry — which usually refuses to provide details of meetings until the very last minute — declined Tuesday to say whether the meeting would take place.

The brinkmanship puts Xi — China’s strongest leader in decades — in perhaps the toughest spot of his six-year presidency. If Xi caves to Trump’s threats, he risks looking weak at home. If he declines the meeting, he must accept the economic costs that come with Trump possibly extending the trade conflict through the 2020 presidential elections.

Whether they meet or not, none of the possible scenarios are good for President Xi or the economy in the long run,” said Zhang Jian, an associate professor at Peking University. “You don’t have a good choice which can meet the needs of the Chinese economy or Mr. Xi’s political calculations.”

Prodded by hawks in Washington to take a “whole of government” approach toward China, Trump may make it harder for Xi to compromise at the negotiating table. The U.S. administration’s efforts to sell arms to Taiwan and criticize China’s mass-detention of ethnic Uighurs in the remote far west of the country are fueling nationalist fears in Beijing that the U.S. wants to weaken and contain its biggest rival.

A separate Bloomberg article revealed that, in addition to the trade frictions, China believes American provocations with respect to Taiwan, and its troubles in Hong Kong, amount to a direct political challenge the Chinese Communist Party`s legitimacy:

Chinese officials have been frank about the seriousness of Trump’s attacks. One senior Chinese diplomat recently told a foreign counterpart that Beijing sees the U.S. actions as a challenge to the Communist Party’s right to govern China, according to a person familiar with the exchange.

Former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd wrote a commentary in the Sydney Morning Herald and stated that he was seeing a marked change in tone from China towards the US. It was a level of belligerence that he hadn’t seen in 30 years, and compromise may not be possible under these conditions [emphasis added]:

Beijing then proceeded to unleash an avalanche of nationalist rhetoric against the US

of a type I hadn’t seen in 30 years. America was now routinely described as a swaggering bully. The People’s Daily reminded its readers that the People’s Republic, less than 12 months after its founding, had fought the US to a stalemate in Korea.Xi Jinping then went south to Jiangxi, from where the Communist Party had set out on the Long March in 1934 and lost 90 per cent of its forces, before finally winning the war against the Nationalists 15 years later. Xi also happened to visit a rare-earths facility in Jiangxi, while not being so crass as to state publicly that America is ultimately dependent on Chinese rare earths for America’s own needs across multiple industry sectors.

The message to the domestic body politic was clear: the world has thrown a lot at China over the last 5000 years, but we Chinese have a long, long history of enduring pain, and we always prevail. Meanwhile, on the policy front, China has calculated that a full-blown trade war, if it comes to that, will cost its economy 1.4 per cent in growth per year. A full range of fiscal, monetary and infrastructure investment measures are already under way as part of a stimulus strategy to keep growth above 6 per cent. Other measures are in the pipeline.

The mere act of meeting Trump in Japan will make Xi appear weak. This time, Trump may have overplayed his hand with his endless threats and the Chinese have begun to view him as an unreliable negotiating partner. Bloomberg reporter Shawn Donnan recently toured China and found that the Chinese are preparing for a protracted trade war:

President Donald Trump is eager to crow about the economic weapon he wielded against Mexico to win concessions on immigration: “Tariffs are a great negotiating tool,” he declared Tuesday.

Now, Trump says, it’s China’s turn to cower. Yet to visit China these days is to encounter the limits of his punch-them-in-the-nose strategy. Even as Trump threatens to raise import duties to painful levels, 10 days of meetings with Chinese officials, academics, entrepreneurs and venture capitalists revealed a nation rewriting its relationship with the U.S. and preparing to ride out a trade war.

Trump is seeking to increase pressure on Xi Jinping, his Chinese counterpart, before this month’s G-20 summit, but Trump may already have pushed too far. Last month, Xi exhorted his countrymen to a second Long March, an echo of Mao’s seminal strategy to preserve the communist revolution. What Xi didn’t say was that the new march — this time in the service of China’s own model of capitalism — is already underway.

“This is definitely an inflection point,’’ said Tom Liu, chief executive officer of Shanghai-based data company ChinaScope Financial Ltd. ”People are seeing an indefinite trade shock.’’ And they are planning for it.

Donnan cited examples such as Huawei’s preparations for an American embargo, Chinese tactics “aimed at spurring innovation and shoring up its economy”, the compilation of “an ‘unreliable entities’ list that would ban U.S. companies that cut off Chinese firms for political reasons”, Chinese companies creating “sanction proof” corporate structures to avoid getting caught up in a trade war, and so on.

From a tactical perspective, reports from official state media China Daily is talking up the possibility of further PBOC stimulus, which could be interpreted as a preparation for a trade war:

Moderate inflation and the global dovish monetary environment may provide more room for the Chinese authorities to adjust money and credit supplies as a tool to counter downside risks if trade tension escalates, said economists.

Stronger counter-cyclical measures are expected in the coming weeks, including possible adjustments of interest rates or the reserve requirement ratio, to maintain ample liquidity in the financial market and support infrastructure investment, according to some economists after they viewed the new financing data released on Wednesday.

It is therefore possible that a trade war erupts because Trump’s threats make it impossible for Xi to meet him without losing face, and China is preparing itself for the consequences. The Chinese has not confirmed a Trump-Xi meeting, and my best case scenario at this point is a backroom deal where no official side meeting is scheduled, but there is an agreement that Trump and Xi could “accidentally” brush by each other in a corridor and decide to retire to a side room to discuss trade issues. Such a compromise could save face for Xi inasmuch as he did not acquiesce to American pressure.

Even if the two presidents were to meet, it will be difficult to see how a complete agreement could emerge from a single discussion. The best the market could hope for is an announcement that the talks were constructive, both sides agree to keep talking, and the US suspends the imposition of further tariffs.

In short, the range of results from the G20 is neutral at best, and catastrophic at worst. While the Fed might choose to cut rates if negotiations collapsed and the US imposed further tariffs, how will the Fed react to a stalemated outcome?

The path of the Fed Funds rate therefore depends on the degree of progress at the G20 meeting. Greg Ip of the WSJ believes that the Fed needs to become the adult in the room:

This is eerily similar to what the Fed faced in early 2003, when growth was tepid and U.S. forces were poised to invade Iraq. “Our degree of uncertainty has gone up dramatically, largely because of…Iraqi oil uncertainty and the other geopolitical risks,” then-Chairman Alan Greenspan told his colleagues on March 18. While leaning towards a rate cut, he advised against moving then since “we are going to learn a great deal about the economy over the next several weeks.” The war began the next day. In June, the Fed cut rates.

Mr. Powell similarly can better judge at the Fed’s July 30-31 meeting whether a full-blown trade war with China is likely and will hammer the U.S. Cutting rates before the Fed can make a clear case with the evidence on hand doesn’t exactly project stability and calm. And the world needs a calm, stable Fed.

If trade risk is grave enough for Mr. Powell to cut rates, either in July or sooner, he will be accused of acquiescing to Mr. Trump’s demands that the Fed support him in his fight with China. He should brush off the accusations. It’s not Mr. Powell’s job to shape trade policy any more than it was Mr. Greenspan’s to prescribe military doctrine. The Fed chairman has to accept such policies as given, then act to protect the economy from the fallout. The biggest risk to the Fed’s independence isn’t Mr. Trump but failing at its job.

How weak is the economy?

The Fed would be fully justified to embark on a rate cut cycle if a full-blown trade war were to break out, but it is difficult to estimate the effects of a trade war. Morgan Stanley recently warned that a recession could begin in nine months if Trump were to impose a 25% tariff of the remaining $300 billion of Chinese imports, and if China were to retaliate with tariff measures of its own.

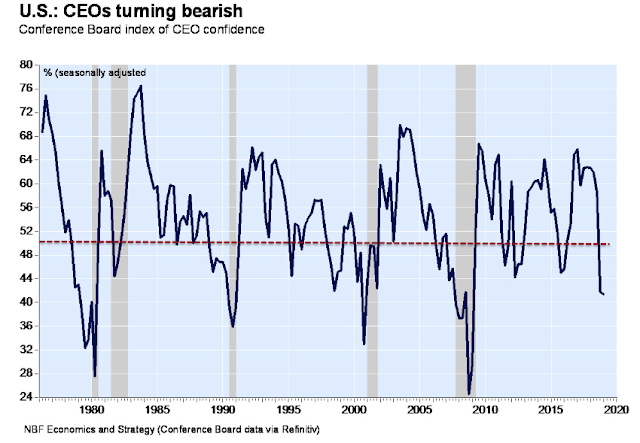

David Kostin at Goldman Sachs estimated the first-order effects of the 25% tariff on $300 billion of Chinese imports to be up to 6% of 2019 earnings, but he was silent on the second-order effects such as the loss of business and consumer confidence, which are very hard to model.

For equity investors, the bearish effects of falling earnings expectations would be offset by the bullish effects of an easy monetary policy. My hunch is the bears will win out in that scenario, as earnings matter more than interest rates.

What if the G20 meeting ended with a neutral result, namely both sides continue to talk and further new tariffs are suspended? How would the Fed react then?

That depends on how weak the economy is. The latest Atlanta Fed nowcast of Q2 GDP growth is 2.1%, and the New York Fed’s nowcast is 1.5%. These figures, combined with the soft May Jobs Report and tame CPI, provide justification for a preventive rate hike.

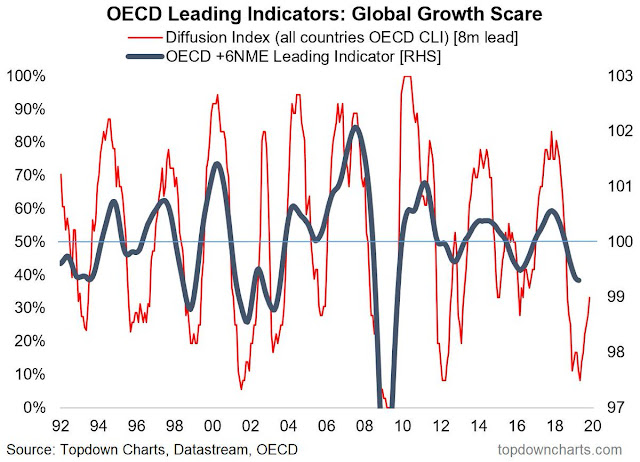

The risk for Fed policy makers is the economy recovers on its on in H2 2019. Callum Thomas pointed out that OECD leading indicators are pointing to a H2 rebound in the global economy. A July rate cut now would be pro-cyclical, which may not be the effect that the Fed wants to convey.

Separate analysis from Richardson GMP of global leading indicators came to a similar conclusion.

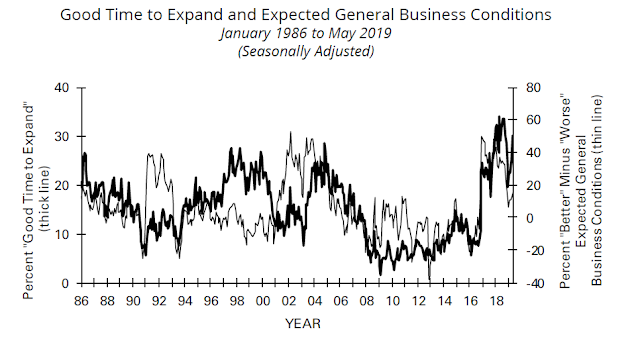

Another set of indicators that I like to monitor come from the NFIB monthly survey, which is useful because small businesses have minimal bargaining power and they are therefore sensitive barometers of the economy. The latest May 2019 NFIB survey shows small business confidence to be on fire. Confidence rose to 105.0 after a late 2018 decline “thanks to strong hiring, investment, and sales,” Unlike the Beige Book or other surveys, there are zero mentions of tariffs.

Expansion plans has rebounded strongly and readings are higher than they have ever been compared to past expansion cycles.

Hiring plans are strong.

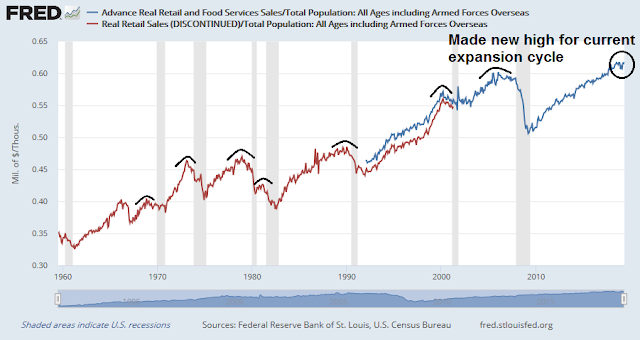

Real retail sales per capita, which is one of my long leading Recession Watch indicators, made a new high for this expansion cycle.

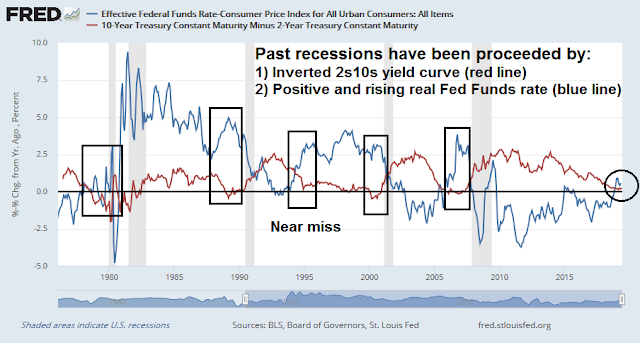

The Fed may be premature in embarking on a rate hike cycle in the absence of downside risk from a full-blown trade war. Past recessions have been marked by a combination of a positive and rising real Fed Funds rate and an inverted yield curve. Neither condition is arguably in place today. The real Fed Funds rate rose into positive territory, but real rates have backed off their highs. The yield curve is only currently showing minor inverted properties, and neither the 2s10s nor the 10s30s are inverted. In fact, the 10s30s spread is above 0.50% and steepening.

Is this the picture of an economy in desperate need of a rate cut cycle?

I believe that if the Fed were to engage in a July “insurance” rate cut under a trade stalemate scenario, the risk is it will have to reverse course later in the year. Potential triggers are a possible natural recovery of global growth, or a trade agreement that resolves much of the downside tail-risk of a full-blown trade war.

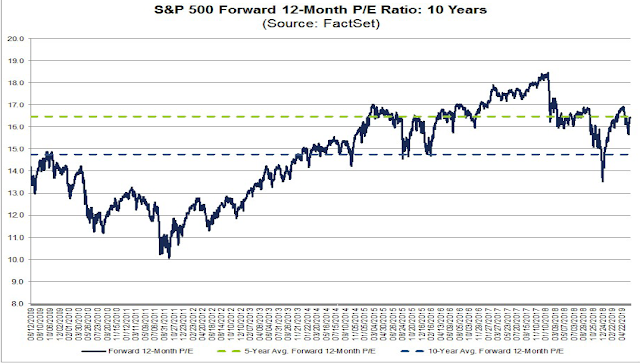

While the resumption of a rate hike cycle may first appear to have bearish overtones for stock prices, the reverse may be true. That’s because the bearish effects of higher rates are likely to be offset by the bullish effects of higher growth expectations. The market currently trades at a forward P/E ratio of 16.5, which is equal its 5-year average and above its 10-year average of 14.8. Stocks are not very expensive and can have room to run if earnings estimates were to resume their upward trajectory, especially when rates are this low.

Strategist Tom Lee pointed out that the equity markets perform well in the wake of a first rate cut, as long as the economy is not in recession. Since 1970, stocks rise an average of 16% nine months after the first rate cut, and P/E ratio expands by 1.7.

In conclusion, while the Fed could decide to cut rates at its July FOMC meeting, the future path of interest rates and stock prices depends on the reasoning behind the rate cut. If the cut is in response to the eruption of a full-blown trade and economic cold war with China, then it is likely to be the start of a protracted rate cut cycle, with bearish implications for equity prices. On the other hand, if the rate cut is an “insurance” cut designed to head off further economic weakness in the face of a stalemated trade dispute, I expect the cut to be reversed relatively quickly because the global growth backdrop remains constructive. Equity prices would rise under such a scenario as the bullish implications of higher growth would overwhelm the bearish implications of higher interest rates.

The week ahead

Looking to the week ahead, it is difficult to make a strong call on short-term direction based on technical analysis in light of the wildcard risks posed by the FOMC meeting next week and the G20 meeting the week after.

As I expected, the SPX started to consolidate and trade sideways after a strong rebound off an oversold condition and panicky sentiment. Short-term readings are overbought, but overbought markets can become more overbought, or they can resolve by either going sideways or correcting.

The weekly chart is equally puzzling and presents a case of fun with technical analysis. If the engulfing reversal the previous week was bullish, why was it followed by a bearish graveyard doji the next week?

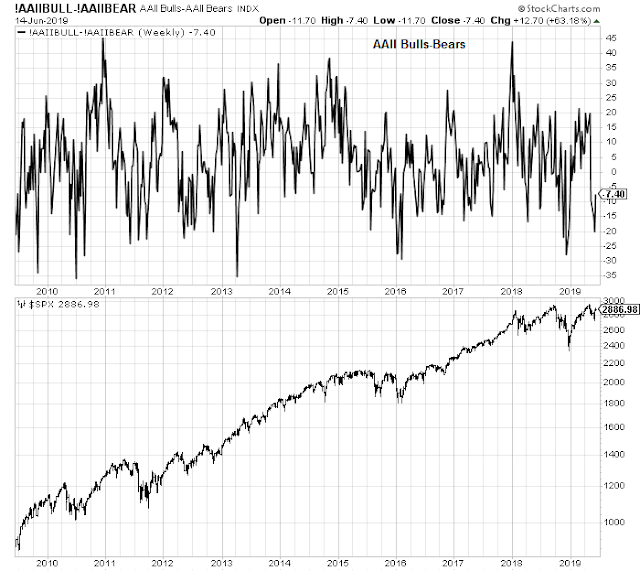

Sentiment models offer little or no directional trading edge as readings have begun to normalize after a crowded short condition. The AAII Bull-Bear spread is just one of many examples. Arguably, sentiment remains bearish, which shows that the market has room to move up before the consensus reaches excessively greedy levels. However, the presence of the twin event risks makes a bullish bet the equivalent of trying to win two coin flips.

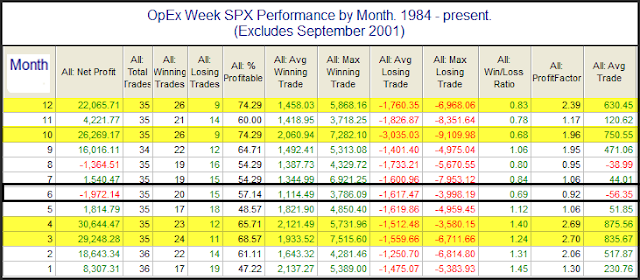

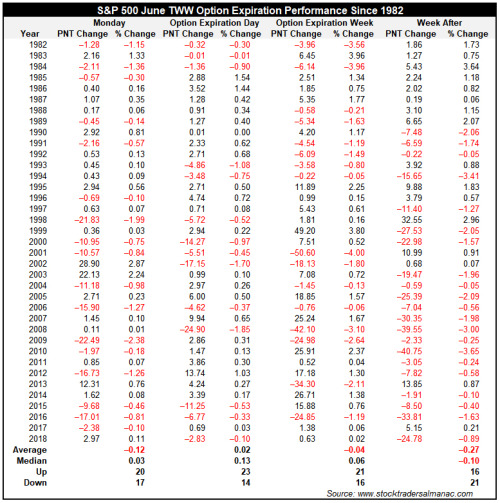

Seasonal patterns offer no directional insights either. Next week is option expiry week, and Rob Hanna at Quantifiable Edges found that June OpEx has a slight bearish bias that offers little or no statistical edge.

A more detailed historical analysis of June OpEx from Jeff Hirsch at Almanac Trader does inspires neither bullish nor bearish confidence.

Market expectations are leaning towards equity bullish outcomes. While the fixed income markets do not expect the Fed to announce a rate cut next week, it does expect hints of a July cut. We can see the effects in the USD Index, which has been trending downwards and it is now testing a key support level. Any hint of hawkishness will send the greenback screaming upwards, but a dovish hold is likely to result in further weakness.

My own naive trade war factor, which is measured by the relative performance of Russell 1000 companies with only domestic exposure, has been tilting towards a “trade peace” in the last week. While Trump and Xi are expected to meet on the sidelines at the Osaka G20 at the end of June, there has been no official confirmation from the Chinese side that a meeting has been scheduled. While this may be just an example of negotiating brinksmanship, benign market expectations is setting up the possibility of disappointment.

Looking out over the valley of the twin event risks, intermediate-term technical conditions are bullish. Both the NYSE and SPX Advance-Decline Lines set fresh all-time highs, which are signals that we are still in a bull market. Tom McClellan agrees with that assessment, and he characterized A-D Line highs as a sign of “plentiful liquidity”, which is intermediate-term bullish.

The combination of an intermediate-term bullish outlook with short-term event risk argues for a neutral investment position. My inner investor is positioned at about the equity weights set out by investment policy. He has selectively sold covered call options against long positions to take advantage of the above average option premiums.

My inner trader has stepped aside and moved to a 100% cash position. There is no point in trading if you don’t have an edge.

Try this near-term RSI5 rule of thumb – See SPX chart above, section mid-Jan to End Feb.

The green area above the 70 line after the start cannot clearly outbalance the area below the line, before the RSI takes a dive to red. Then a new section has to start.

(If momentum cannot go forward, it must reverse.)

Not much time left.

Any chance on getting the Trend Model Trading Results? Thanks

Cam, you did not highlight the publicly announced three red lines drawn by China in Kevin Rudd’s article in the Sydney Herald. I thought that was important. I can see the US yielding to all three red lines. If that is the case, haven’t the odds improved of a positive outcome coming out from the G20 meeting?

Backtracking on the extradition bill after the protests in Hong Kong shows that Beijing is capable of retrenchment without losing face.

The three red lines are:

1) Rescind all tariffs

2) Set a realistic limit of what China buys from the US (apparently a figure was agreed between Trump and Xi at the BA G-20 and the Americans tried to raise that)

3) Mutual respect in negotiation (subtext: don’t make us change our way of doing things)

The developments in HK makes me more pessimistic about the prospect of any deal. Apparently there is a widely held belief that the CIA had instigated the protests, and the fact that Carrie Lam had to back down is seen both as an attack on China, and a humiliation (see 3 above). Xi can’t be seen to lose face.

Thank you, Cam.

I don’t understand why the stock market is still trading near the highs. Like you say, lower interest rates cannot offset the impact of the trade war. The earnings will be hurt in short-term at least. In the medium- and long-term, 2nd and higher order effects will be even more onerous for everyone if the supply-chains (huge amount of capex and disruption) need to be re-built and confidence among businesses to be restored.

In the absence of trade tensions, everything looks good. The economy is coming off the boil, valuation is a little elevated but not wildly expensive, and the Fed is making dovish noises. Why wouldn’t you be buying?

The big questions are:

1) How dovish is the Fed, really?

2) What happens with trade?

We’ll have a better idea in about 2 weeks.

My concerns center around trade. I think the market is not discounting properly the risks of a perpetual trade war and the ongoing tech rivalry. The latter may split the world into separate technology standards and trading blocks with China controlling deployment of technology in parts of Asia (incl. Central Asia), Africa and the parts of Latin America, and the US in the rest of the world. That will be very harmful and costly.

I hope we will have some answers at G20.

I agree with Cam that Trump may be making it harder for Xi to compromise at the negotiating table. I found the threat of more tariffs if Xi does not meet him at G20 particularly aggressive. With Democrats running to the right of him on China, he may have decided to remain looking tough on China rather than agree to a deal that may have the appearance of looking weak. Run for re-election as a Tariff Man, and not as a Dow Man.

Does anyone think this to be a plausible scenario?

I have no idea of what is going on in Donald Trump’s head. If anyone does, they would make a lot of money.

My best guess is he has miscalculated and overplayed his hand.

A wildcard is the fate of Huawei and ZTE which rests in the hands of Trump and Xi. The two companies might have buildup enough inventory to last 6 months or a year. So, Xi Jinping got some time. But at some time, he needs to protect the national champions. Will he strike a deal to save them from oblivion like he did to save ZTE last year? If Huawei goes down, how harshly does China return the favor (and so on and on)? Will they stop the assembly of iPhones and destroy and an American icon?

If the supply-chain sees massive disruption over coming months and years, can Trump withstand pressure from the businesses?

Huawei as a brand name is likely to suffer, but the underlying technology will most likely be sold under different brand names. I guess many Huawei engineers are already working on new smartphone designs with the “Oppo” brand. On telecom equipment, watch for new Chinese companies to emerge, I would be surprised if Huawei managers had not already established a network of smaller subcompanies under direct or indirect control of current Huawei executives.

There is nothing that prevents the US to apply the same export restrictions to new Huawei “spin-offs,” if they are perceived to be security risks.

The news today of much lower 2019 Huawei revenue is attributed to lower smartphone sales. Lower telecom equipment sales would be next because of shortage of chips and optical components supplied by the US companies.