In the past week, two key elections have been held that have important geopolitical, economic, and investment implications. First, remember this Time magazine cover? I indicated on February 6, 2017 that the cover may have marked Peak populism.

I suggested at the time to buy France and sell Germany as a pairs trade. That trade has certainly worked out well. Now that Emmanuel Macron is destined to be the President of France, and Angela Merkel is the front runner to win another term as German Chancellor, challenges lie ahead for French-German cooperation in the eurozone. Macron has voiced his objective of greater European integration as part of his electoral platform, the question is, “How much integration is Germany willing to accept?”

As well, I wrote on April 17, 2017 that the US had few good options in dealing with North Korea (see The Art of the Deal, North Korean edition). Now a further political development is certain to cause both Trump and the American foreign policy establishment headaches, namely the election of Moon Jae In as the President of South Korea. The South Korean KOSPI Index has rallied in the wake of this electoral result, but the likely loser in any geopolitical settlement engineered by Moon is the United States.

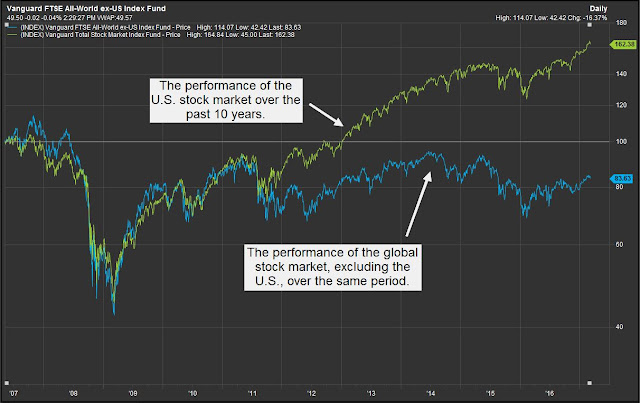

Marketwatch recently featured a story indicating that investors should look to non-US equity markets for future gains, as valuations are far more compelling overseas. Not so fast! The story is more nuanced than that. The resolution of the situations in Europe and Korea have profound investment implications. As well, they have the potential to set the world on some very different paths for the next decade.

Time for Germany to choose

The various PIIGS eurozone crises of the last ten years have exposed the vulnerabilities of the euro. Monetary integration without political integration have created fault lines that could crack open the European Project (see The miracle of Europe). Simply put, monetary union without fiscal and political unions is a contradiction. The problem for Europe is implementation. The last time Europe had a political union was in 1941, when Hitler’s armies overran the continent. That experiment in forcible political integration didn’t work out so well .

Fast forward to the modern era. Angela Merkel made a speech in June 2012 calling for greater fiscal integration in the wake of the Greek debt crisis (via Credit Writedowns):

“We need more Europe; we need more cooperation,” said German Chancellor Angela Merkel. She is now calling for a joint budget policy and expanded political union for Europe.

-Deutsche Welle, June 2012

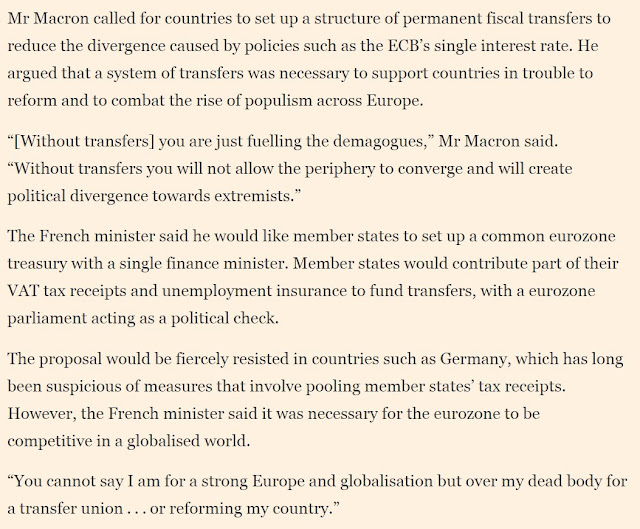

More recently, Emmanuel Macron called for eurozone fiscal transfers in 2015 (via FT):

Now it`s time to put up or shut up. In the wake of Macron’s victory, various commentators have raised the question of how far Germany is willing to down the fiscal integration road. Here is just a sample:

- Angela Merkel should seize this chance to remake Europe (The Economist)

- Wahl in Frankreich: Angela Merkels Moment (Süddeutsche Zeitung)

- How will Germany respond to Emmanuel Macron? (Center for European Reform)

The main points of the commentaries are all the same. Germans are divided, but they have a golden opportunity to reform Europe in partnership with their main EU partner, France. Here is how The Economist summarized the issues:

German celebrations of Emmanuel Macron’s victory had barely begun last night when the first arguments about it broke out. The French president-elect’s longstanding calls for a “new deal” between his country and Germany were the impetus. In return for French structural reforms and fiscal restraint Mr Macron wants Berlin to support the closer integration of the euro zone, including joint investment projects, Eurobonds (common debt) and a finance minister, budget and parliament for the 19-state currency area. All of which drives a trench through the Berlin political landscape.

On the one side are most in the centre-right CDU/CSU, the liberal FDP and especially in the finance ministry under Wolfgang Schäuble, the CDU finance minister. This camp opposes all of Mr Macron’s most ambitious proposals. It is backed by the majority of public opinion and the Bild Zeitung, Germany’s most-read newspaper. And it tends to the belief that the country already pays disproportionately into the European project, that its current success was built on tough reforms in the last decade and that struggling Latin economies like France need to go through the same painful but necessary process. This outlook has deep cultural roots in Germany’s aversion to loose money; the word for “debt” in German is the same as the word for “guilt”.

On the other side are most of the centre-left SPD, the Greens and the foreign ministry under Sigmar Gabriel, the SPD politician who counts Mr Macron as a personal friend. On at least some points they are joined by internationally-minded CDU figures like Norbert Röttgen, the chair of the Bundestag’s foreign affairs committee who is close to Jean Pisani-Ferry, Mr Macron’s top economist. This camp, backed by the liberal and centre-left broadsheets, worldly think-tanks and much of German Brussels, tends to stress the advantages Germany has reaped from the euro and to argue that it should put its wagging finger away and acknowledge a responsibility towards weaker members of the club.

The idea of a eurozone finance ministry is precisely the sort of measure that Merkel proposed in 2012. On the other hand, eurobonds, or joint liability, is probably an overly ambitious objective (at least for the current round of negotiations). Nevertheless, there is probably a compromise solution to be had after all of the horse trading is done.

The outlines of a mutually acceptable “new deal” are clear. Closer defence and security co-operation (France is trying to cut spending, Germany has committed to spending billions more) will come easily. And even on the euro zone, argue Thorsten Benner of the Global Public Policy Institute in Berlin and Thomas Gomart of the Institut Français des Relations Internationales in Paris, there is a compromise to be forged. This would start with Mr Macron and Mrs Merkel promptly creating a Franco-German investment fund, committing jointly to a multi-speed Europe (an idea to which the chancellor has warmed in recent months) and forging a new front against authoritarianism in Poland and Hungary.

If Macron and Merkel can`t make a deal after the September election, then Germany may have to face President Marine Le Pen in five years’ time.

As Mr Gabriel has pointed out: “If [Mr Macron] should fail, Ms Le Pen will assume the presidency five years from now and the European project will be thrown to the wolves”. Amid the relief in Berlin, some here lose sight of the facts that almost half of French first-round voters backed candidates of the nationalist far-left or far-right, that just a few percentage points here and there prevented a run-off between those two extremes, and that Ms Le Pen could yet usurp Mr Macron in 2022.

If she does, and the euro zone falls, Berlin will feel the consequences. Its economy is built on supply chains that wend their unimpeded way around the continent. Its whole international vocation depends on its European identity. Germany cannot pretend France is just another country, just another line on the spreadsheet. As Willy Brandt said of his nation’s reunification: “Things grow together which belong together”. France and Germany are at once so foreign to one another, so temperamentally and historically different. Yet they are also natural allies and irredeemably interdependent. If Macron fails, Europe may fail. And if Europe fails, Germany fails.

Mrs Merkel can prevent this. German public opinion may not be favourable to Mr Macron’s sensible proposals. But the chancellor is powerful and popular. She looks set to win a fourth term in September and is not likely to seek a fifth one four years later. She has taken calculated gambles before: transforming Germany’s energy supply from 2011 and letting in hundreds of thousands of refugees from 2015. She has enough political capital in her account for at least one more splurge. Europe’s future is surely worth the outlay. “From September onwards it will be all about Merkel’s legacy,” Mr Benner tells me: “And letting the only plausible route to strengthening the German-French relationship for the greater good of Europe go to waste and preparing the ground for the extremes to take over France is nothing you want to be remembered for.” He has a point.

Here is what`s at stake for investors. The chart below shows the 10-year relative performance of FEZ (Euro STOXX 50) ETF against SPY. Both ETFs are USD denominated so the chart accounts for currency effects. Eurozone equities have been underperforming US equities for the entire period, but have shown several episodes where they seem to turn around on a relative basis. The big question is whether the latest turnaround is another fakeout, followed by more European underperformance.

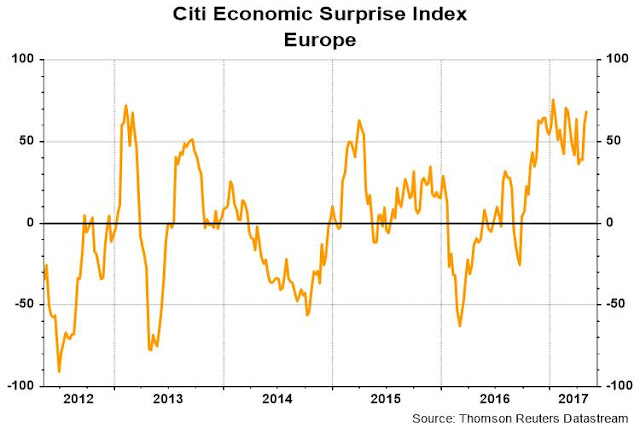

The latest revival is attributable to two factors. The first is cyclical. The European Economic Surprise Index surged in late 2016 and readings remain elevated, indicating that macro-economic releases are coming in well ahead of expectations.

By contrast, the US ESI followed the same pattern of a reflationary rise in late 2016, but have tanked in the past few weeks.

The second reason is Macron’s electoral win, which took political tail-risk of European disintegration from a Le Pen victory off the table. If European equities are to continue to outperform, then Angela Merkel will have to spend the political capital “for at least one more splurge”.

Investment expectations are already high. The latest BAML Fund Manager Survey shows that institutional managers are in a crowded long in eurozone equities. Any political disappointment will see these stocks resume their downward slide against their US counterparts.

In the meantime, watch for the FEZ/SPY pair to either pull back or consolidate until the German election in September when these difficult questions will begin to get resolved.

Korea: Peace in our time?

On the other side of the world, the US faces a different dilemma on the Korean peninsula, and it has nothing to do with Kim Jong Un of North Korea. Jonathan Pollack at the Brookings Institution wrote this profile of newly elected South Korean President Moon Jae In. Moon wants to soft the hard line stance against North Korea. He has made it clear that his ultimate goal is peaceful Korean reunification.

On April 23, Moon disclosed his larger strategies in a thousand-word statement entitled “Strong Republic of Korea and the peaceful Korean Peninsula.” There is a Rip Van Winkle quality to the document, almost as if North Korea’s defiant, determined pursuit of nuclear weapons and missile delivery systems in the intervening decade had not occurred. At the precise moment when the international community has begun to grasp the fuller implications of North Korean nuclear and missile development and when the United States and China have moved closer to a coordinated strategy to inhibit Pyongyang’s advances, Moon seems intent on turning back the clock…

Moon foresees a Seoul-centered process whereby South Korea will lead and orchestrate a return to the six-party process, with South Korea creating a “new framework of inter-Korean relations.” But aspirational goals outlined in his policy document (including making Korea a nuclear-free zone, the signing of an inter-Korean peace treaty, and pursuit of a “mutual arms control agreement in stages”) are slogans contrary to ongoing efforts to curtail North Korea’s nuclear ambitions. Renewed engagement also plays on emotional sentiment favoring unconditional accommodation with the North and would enable Pyongyang to again influence South Korean domestic politics. This story did not end well under Roh Moo-hyun, and the risks with a nuclear-armed North are incalculably higher.

Moon openly advocates a return to the discredited “Sunshine Policy” first established under the late president Kim Dae-jung, and then pursued more vigorously under Roh Moo-hyun. Moon’s calls for the unconditional resumption of previous inter-Korean accords—to be ratified and enacted jointly by the South Korean National Assembly and North Korea’s nominally equivalent body, the Supreme People’s Assembly—and creation of a “common economic community” would presumably open the sluice gates of economic assistance to the North, which confronts growing economic pressures imposed by multilateral and national-level sanctions.

Moon wants to reunify the North and South. As part of that process, he wants to effectively Finlandize the Korean peninsula. A neutral Korea would not offend Chinese sensibilities of having unfriendly troops on their border.

Peace in our time, right?

The proposal, if implemented, have profound geopolitical implications for the region. Sure, the de-nuclearization of North Korea and a peaceful reunification of the North and South would rachet down the doomsday scenario of a regional war that could turn nuclear. But the big loser under such a scenario would be the United States. Finlandization of the Korean peninsula means a neutral Korea, and it would necessitate the withdrawal of American troops. As South Korea is already a major exporter to China, it would draw the reunified Korea closer into the Chinese political orbit.

The real wild card is how Donald Trump reacts to Moon’s initiatives? On one hand, he has balked at paying the $1 billion cost of deploying the THAAD missile system in South Korea and this would be consistent with his America First policy. Bloomberg reported that he had hit the roof when General McMaster indicated to his South Korean counterparts that the US would pay for the deployment of the missile system, for now:

Trump was livid, according to three White House officials, after reading in the Wall Street Journal that McMaster had called his South Korean counterpart to assure him that the president’s threat to make that country pay for a new missile defense system was not official policy. These officials say Trump screamed at McMaster on a phone call, accusing him of undercutting efforts to get South Korea to pay its fair share.

On the other hand, watch for rumblings from the American foreign policy and defense establishment about Moon’s softer policy on Pyongyang. Will future American historians be debating the question of “who lost Korea” in 10 or 20 years’ time?

Bloomberg recently documented how vulnerable the global economy is to a war in Korea because of the integration of Korean semiconductors in the global supply chain:

The country’s chipmakers produce almost two-thirds of the world’s memory semiconductors, thanks to the dominant role of SK Hynix and Samsung Electronics Co. Samsung also produces chips for customers like Qualcomm Inc., the world’s largest maker of semiconductors for phones. “If Korea is hit by a missile,” Soo Kyoum Kim, a vice president with IDC Research Inc., said in an email, “all electronics production will stop.”

About 12 percent of Apple Inc.’s suppliers are from South Korea, according to data on supply chains Bloomberg compiles. The U.S. company is LG Display’s biggest customer and may become even more reliant on Korean exports with the introduction of the iPhone 8, at least one version of which will likely have an OLED screen. Korean factories turn out about 40 percent of the world’s LCDs and almost all of its OLEDs, according to Alberto Moel, an analyst with Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. For high-end displays, he says, “it’s basically them or nothing.” The analyst pegs the cost of replacing the display manufacturing capacity of LG and its main rival, Samsung Electronics, at about $50 billion.

In light of this election, the wildcard is no longer just Comrade Kim, but the reaction of President Trump. How will he respond to the Moon election? How will he view his legacy? More importantly, what will the Sunday talk shows say about Korea that forces him to react?

These are all very good questions for both Europe and Korea. The answers to those questions are well beyond my pay grade. Stay tune for more developments.

This makes for a great read. Thanks.

Reading this is scary.

For national security all chips and displays, etc, …., used in the USA and by our allies should have a mandated backup plan to be made in the USA. There has to be some kind of backup plan for stuff to be made even if the plan is to have the “How to Make the Widget”, is the previous widget generation.

When the US sells F-15 fighters to Saudi Arabia, is it reasonable for the Saudis demand a “how to make it” contingency plan?

Discuss.