The main events in the coming week will be the interest rate decisions by Federal Reserve on Wednesday and the ECB on Thursday. Both are widely expected to raise rates. However, market expectations for the trajectory of the U.S. Fed Funds rate is a 25-basis-point hike at the May meeting, a pause, and rate cuts later in the year. By contrast the ECB is expected to continue hiking.

On the other hand, the ECB path is more hawkish and its rate hike cycle does not appear to be complete. The governing council is reportedly split between a 25-basis point and a 50-basis point hike at the May meeting. ECB board member Isabel Schnabel told Politico in an interview that underlying inflation, which filters out volatile food and energy prices, shows very strong momentum and it was not clear that it would peak “very soon”. Belgium’s central bank head and ECB setting governing council member Pierre Wunsch told the Financial Times in an interview: “We are waiting for wage growth and core inflation to go down, along with headline inflation, before we can arrive at the point where we can pause.”

The Fed hates to surprise markets. A 25-basis-point rate hike is a virtual certainty. Unless it doesn’t plan to pause increases after the May meeting, it will signal its intention next week, subject to the usual caveats about data dependency. The challenge for investors is how to position themselves should the Fed pause.

Due for a pause

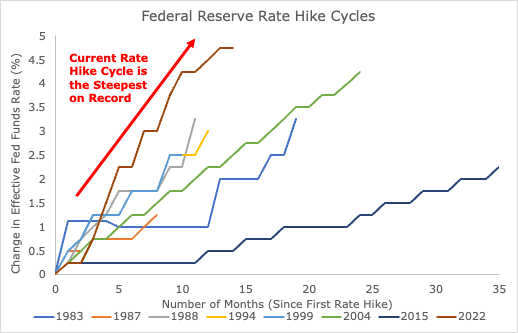

A pause should be no surprise. This has been the fastest and steepest rate hike cycle, ever. As monetary policy operates with a lag, it makes sense to pause tightening in order to measure its effects, now that monetary tightening is no longer accommodative.

Numerous signs are appearing that the Fed is tightening into a slowdown. Bespoke Investment Group pointed out that U.S. leading indicators have declined for 12 straight months.

Cyclical indicators, such as the copper/gold and base metals/gold ratios, and risk appetite indicators like the relative performance of global consumer discretionary to global consumer staple stocks, are signaling a risk-off environment.

The New York Fed’s yield curve-based recession model is also pointing to a hard landing ahead.

What happens next?

What happens next? I studied the capital market reaction when the Fed stopped raising rates. There have been nine distinct episodes since 1980 when the Fed stopped raising rates. Here are how the different markets responded to the final rate hike. The charts show the median and the maximum and minimum rates of return for different asset classes after each of the final rate hikes, with the starting point indexed at 100 in the case of stock market indices, and at zero in the case of yields and yield spreads.

The S&P 500 showed considerable variation in returns over the study period, but the median market response (solid dark line) shows that the index was flat to down about two months after the initial Fed decision, followed by gains afterwards. However, there was a distinct difference between the cases when the Fed stopped raising rates when the yield curve was inverted and when it was not. With the caveat that we are looking at a small sample size, S&P 500 returns when the yield curve was normally inverted (red line) underperformed the median and instances when the yield curve was upward sloping (blue line).

By contrast, I found little difference between the response of the 10-year Treasury yield and yield curve regimes in our study. The median 10-year Treasury yield tended to edge up after the initial Fed decision, followed by a steady decline.

There were, however, two outliers that were partly omitted from the historical study as they may give readers the wrong impression of the maximum or minimum in the analysis. The first was the rate hike of December 1980.

This instance was unusual inasmuch as it occurred during the double-dip recession of 1980–1982 and during the tight money era of the Volcker Fed. The 10-year Treasury yield rose for much of the next 12 months. The period was excluded from the Treasury yield study but it was included in the S&P 500 study.

The second outlier was the final rate hike of September 1987, when the Fed raised rates multiple times on an inter-meeting basis to defend the USD. The rest, as they say, is history. This was excluded from the S&P 500 study as it may create an outsized expectation of downside equity risk.

The silver lining

In conclusion, the Fed appears to be tightening into a slowdown. If history is any guide, the S&P 500 is likely to exhibit subpar performance in the coming year, while 10-year Treasury yields decline and bond prices should see some gains.

The one silver lining to this apparent dire scenario is the world is unlikely to fall into a synchronized global recession. In particular, China is stimulating its economy. It already made an about-face away from its zero-COVID policy early this year, and the PBoC is pivoting toward a more stimulative monetary policy.

Fathom Consulting’s estimate of Chinese GDP is already on the rebound, and if earnings results from luxury goods producer LVMH is any guide, Chinese consumers are going on a spending spree.

I reiterate my view that equity investors should find better bargains outside the U.S. (see The market leaders hiding in plain sight). European equities have staged a relative breakout. Asian equities are consolidating sideways and investors should monitor them for signs of upside relative breakouts.

I recently finished reading the book The Price of Time, The Real story of Interest by Edward Chancellor. This is an amazing book that lambasts the actions of global central banks. Strongly recommended.

By many metrics, the world is changing and what worked in the last two decades may not work in the next two decades. Here are two articles that discuss changes in pipeline.

https://themarket.ch/interview/russell-napier-the-world-will-experience-a-capex-boom-ld.7606

https://themarket.ch/english/transitioning-from-an-era-of-plenty-to-an-era-of-shortages-ld.8077

Good post and helpful.

From portfolio perspective, it argues for lower US equity allocation and higher Developed market allocation; increasing the bond portfolio duration.

Couple of points:

1. Latest survey by University of Michigan shows uptick in short term and longer term inflation expectations. One year at 4.6% and five year at 3%. Not good news for the Fed.

2. ECB is continuing to raise rates could lead to slowing growth there as well. China’s growth may be tempered as well.

Fed is unlikely to announce a definitive pause. It will be debated ad nauseam by pundits on both sides.

Does who gets hurt matter?

In the 30s, there was huge pain, it was the bank failures, the credit markets got damaged. Nobody wants that.

In the GFC it was credit markets again that were at risk.

It’s like the joke about coming back to life as the bond market.

So I don’t think that the equities markets have much say in the matter. If they crash and stay down means only that those holding stock options won’t score big, and IPOs won’t sell as well. Many bag holders, me included will suffer but as long as credit flows the system is ok.

The dollar matters, but not if the change is gradual. If the euro is 1.00 or 1.25, what does it change for most of us? Nothing.

But if your credit cards don’t work, the grocery stores don’t work, then we have a big problem. Call it the BPE, Biggest Problem Ever!

Of course they want a pause and a pivot, but if we have a hard time borrowing and spending and the economy slows and inflation is lower because demand is down, does this matter? I don’t think so.

Think in terms of a sadist and his masochist buddy (disclosure, this is not a recommendation for a personal life style), the sadist causes the masochist loads of pain, he won’t stop unless he thinks Mr. Maso is about to die.

So we may get this long pause and no pivot until something that affects the credit markets is ready to break.

How much potential contagion is out there? All these credit default swaps or whatever? Buying insurance is smart provided your insurer stays solvents…that was at the heart of the GFC I think.

The last 2 times the US2 year went down, it went down hard, as did the market, so we don’t want a pivot unless we are long duration bonds. A pause at what historically are normal rates would be good.

If you follow Hussman or Easterling, they both say the same thing. We are in for low returns for at least a decade is the most likely outcome.

Once upon a time, there was the pound and the guinea. The guinea was for nobility.

So if the gov’t cannot handle high interest rates on it’s debt, who says they cannot make a 2 tier system? If interest rates can go negative, what is not possible?

Look at the chart of $UST20Y, it goes back to 1990. Something big is happening.

One path if deficit spending continues is rates crash again, because if fiscal deficits get to where the interest cost eats everything up, things fail.

Or make interest rates at the government level irrelevant, call it Fiat 2.0, so they can spend as they wish, we have to deal with interest rates that the market determines which will cause cyclical credit ebbs and flows

The gov’t wants to keep it’s important job of staying in power and if debt costs make buying votes impossible, that’s got to go.

It’s not impossible.

History and rhymes.

In 1989-1990 worried about inflation and a stock market bubble the BOJ raised interest rates steeply from 2.5% to 6 %, and look what we got.

Now we had a bubble, inflation and a Fed rapidly raising rates. Will there be poetic justice?

https://www.yahoo.com/finance/news/dollar-dominance-could-way-tripolar-182500899.html

Anyone think this is possible?

It’s already happening. I can easily see more and more bilateral agreements to settle trades in a non-USD currency. It can probably accelerate in Global South (incl. ME and Russia) as more and more trade is settled in RMB and even in INR.

I think it will be harder to crack USD’s role as a reserve currency in near-term. But I trust our government will find a way to reach that goal in a few decades.

The euro is a “flawed” currency in the sense that all the members have their own policies. The yuan is subject to the whims of the CCP.

But I think what really matters is trade. As the Chinese economy grows in size, more people will of necessity use the yuan, ditto the euro.

The USD is on legacy from 80 years ago when it truly was dominant, but like in chemistry where one needs energy of activation, things will likely keep going on because change is hard, and how do you price things?

So it’s possible, but will likely take time. Give enough time and it’s inevitable.