China has a well-known demographic problem: its working population is aging quickly. For years, many analysts have rhetorically asked whether China can get rich before it gets old.

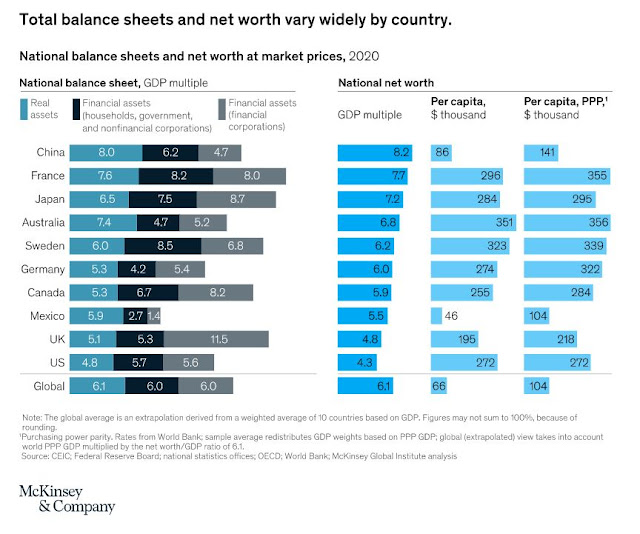

Unbalanced wealth

Among the 72 billionaires, 15 were murdered, 17 committed suicide, seven died from accidents, 14 were executed according to the law and 19 died from diseases.

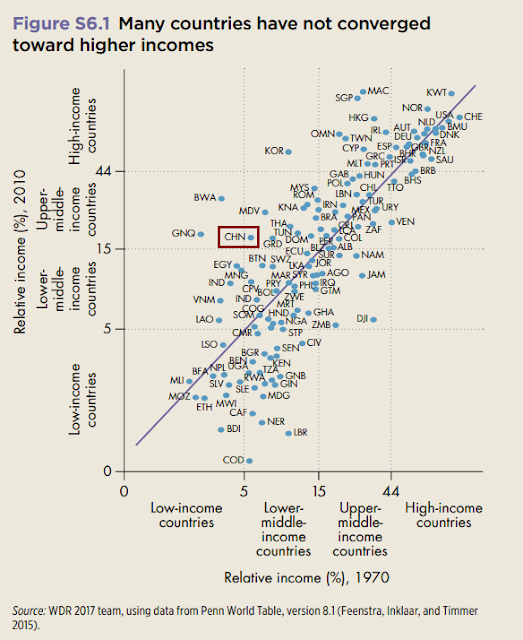

The middle-income trap

Middle-income countries may face particular challenges because growth strategies that were successful while they were poor no longer suit their circumstances. For example, the reallocation of labor from agriculture to industry is a key driver of growth in low-income economies. But as this process matures, the gains from reallocating surplus labor begin to evaporate, wages begin to rise, and decreasing marginal returns to investment set in, implying a need for a new source of growth. Middle-income countries that become “trapped” fail to sustain total factor productivity (TFP) growth. By contrast, “escapees” find new sources of TFP growth (Daude and Fernández-Arias 2010). Indeed, 85 percent of growth slowdowns at the middle-income levels can be explained by TFP slowdowns (Eichengreen, Park, and Shin 2013).

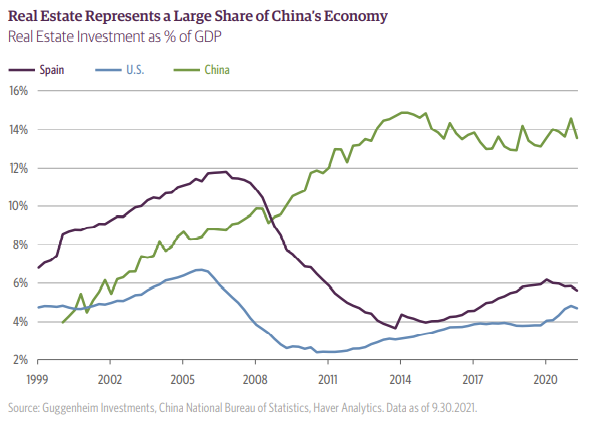

The World Bank hit the nail on the head with its formulation of TFP growth as the key to avoiding the middle-income trap. China faces two main challenges in maintaining growth. First, its GDP growth at any cost model has incentivized provincial cadres to focus on unproductive credit-driven real estate growth. The teetering finances of China Evergrande and other property developers have exposed the limits of this growth model.

As well, it faces the more conventional problem of migrating up the value-added chain as “the gains from reallocating surplus labor…evaporate”, as per the World Bank. Indeed, the SCMP reported that vice-premier Liu He penned a long article in China’s Daily about Beijing’s plan to avoid the middle-income trap by relying on technological innovation.

“Since the end of World War II, there are many countries that have started the industrialisation process and even briefly stepped over the threshold of being a high-income country,” Liu wrote. “Yet only very few countries, such as South Korea, Singapore and Israel, have truly leapt over the middle-income trap.”

To become an advanced economy, China has to shift its growth model from a strategy “driven by inputs” to an approach “driven by technological innovation” – a process that is still in progress, according to Liu.

Liu’s article, which argues for China to embrace “high-quality” growth and lays out ways to achieve that goal, is consistent with the World Bank and the State Council’s joint report a decade earlier. Worries about the sustainability of China’s growth persists, and the role of innovation in solving that problem is highlighted.

What does “high quality” growth mean? First, it means avoiding low-quality growth such as credit-fueled growth based on investment in unproductive real estate. Moreover, it means a pivot to high value-added technology services from low labor cost manufacturing.

Yukon Huang and Jacob Feldgoise pointed out in an SCMP Op-Ed that virtually all countries have experienced declines in manufacturing. Taking the US as an example, the process of de-industrialization was accompanied by a surge in knowledge-intensive industries, which represented a bright spot in America’s growth path as shown by this Brookings study. As China attempts to move up the value-added chain, they argue that a Sino-American trade agreement for knowledge-intensive services would substantially benefit both sides. Whether there is sufficient political will in Washington and Beijing to complete such an agreement is an open question.

China’s report card

If that is the growth path laid out by Beijing, how is China doing?

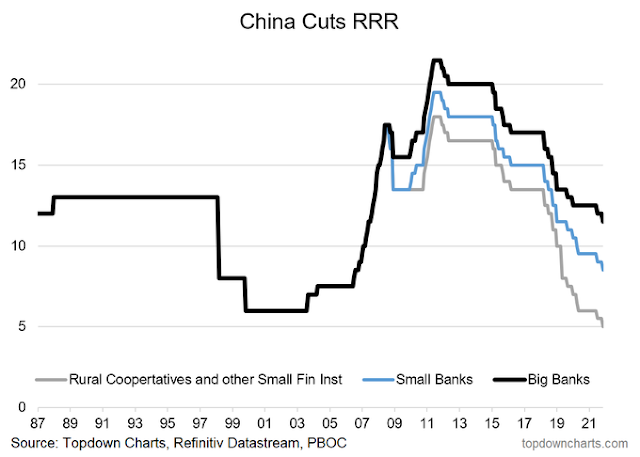

“The tone has turned much more dovish,” Macquarie Group Ltd. analysts led by Larry Hu wrote in a Monday note. “For the first time, the Politburo meeting uses the phrase ‘stability is the top priority.’ In other words, top leaders are deeply concerned about the risk of potential instability.”

China’s population may be aging, but I’m guessing life expectancy has also increased markedly in the past twenty years. It’s also been the case that life expectancy in Asian countries (Japan and HK, for instance) exceeds that in the US by an average of 6-7 years – not sure why that is.

Cam and others,

I think this FOMC meeting may turn out to be pivotal. Both Democrats and the Fed are now more worried about sustainable inflation in front of the 2022 mid-term. Powell has already dropped the use of the word ‘transitory’ and is on board to speed up the taper. It is entirely possible that Jay Powell will sound even more hawkish than the market is expecting him to be. If he signals the possibility of 3-4 rate hikes in 2022, the long-duration and very risky assets (think ARKK and high-growth tech / bio tech names still losing money) as well as the interest rate sensitive names (utilities) may crater more even after the recent bloodshed in many of those names. Some inflation-sensitive names may also drag along downwards.

What are you guys expecting from Jay Powell this week?

I think Powell will be just repeating what everyone already knows and Market already prices in. If market price movements on Friday is any indication when CPI is so high, then we might have a rally.

After Friday’s CPI numbers came out the inflation expectation drops. I hope wisdom of the crowd still holds.

At this moment price momentum is high. Institution expectation for a rally is high while that of retails is low. I don’t know which is dumb or smart money.

The consensus seems to be that they’ll double their taper, which puts them on track to end QE by March and opens the door for a May rate hike.

What are the implications of changes in Chinese economy for US and other developed markets, if any! So far, it seems China has somewhat decoupled.

Yes, they have decoupled. Weakness didn’t affect the ROW much.