An unusual labor market shift has occurred since the onset of the pandemic. Employers everywhere are complaining about a lack of quality employees. The Beveridge Curve, which describes the relationship between the unemployment rate and the job opening rate, has steepened considerably.

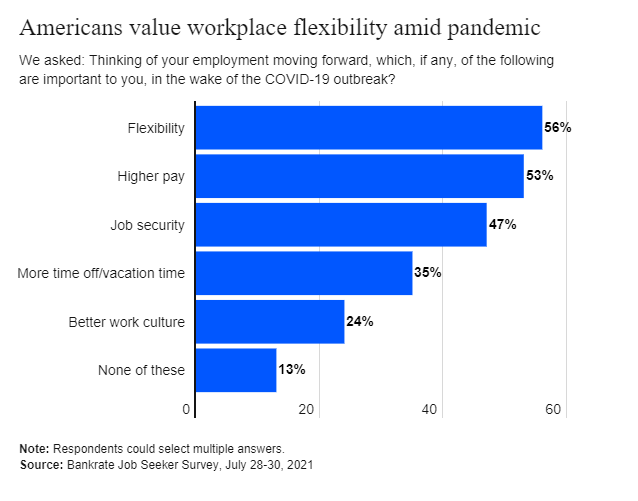

Workers are not returning to their jobs, at least not without considerably more incentives. Some factors that affected labor supply are temporary and should moderate over time, such as the fear of catching COVID-19 and childcare availability, but many people are reassessing their priorities in the wake of the pandemic. They call it the “Great Resignation”.

Tens of thousands of labour union members took to the streets across South Korea on Wednesday (Oct 20) to demand better working conditions for irregular workers and a minimum wage hike.

This was despite repeated government warnings that the rally was illegal and violated Covid-19 restrictions.

In Canada, the Globe and Mail reported that a Bank of Canada survey found widespread concerns about labor shortages:

The business outlook survey found Canadian companies optimistic about future sales growth, but experiencing significant capacity constraints. Sixty-five per cent of respondents said they would have “some difficulty” or “significant difficulty” meeting an unexpected surge in demand.

The biggest issue is labour. Although Canada’s unemployment rate remains elevated, at 6.9 per cent last month, companies are having trouble attracting workers. Just more than a third of respondents to the business survey said labour shortages were restricting their ability to meet customer demand. Moreover, 71 per cent of respondents said labour shortages were more intense than a year ago, while only 7 per cent said they were less intense.

What’s going on? What does that mean for the economy and what are the investment implications of the Great Resignation?

A Great Reshuffle

The Great Resignation can be viewed through different lenses. First, a Gallup poll revealed that views of the job market are at a historical high. Tightness in the labor market is very real.

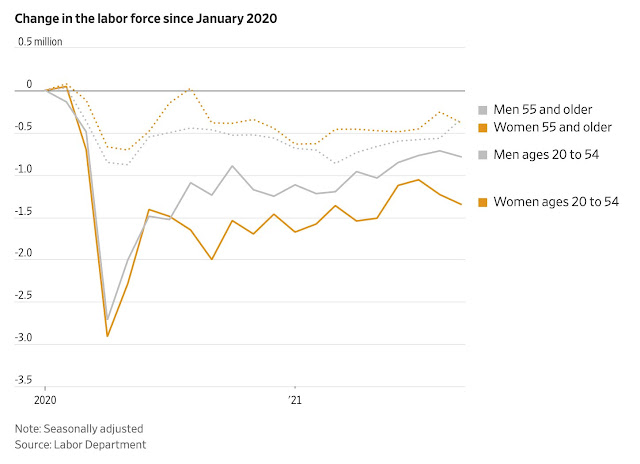

If we segment population by age, the Great Resignation is actually a demographic-related Great Reshuffle, which is what LinkedIn CEO Ryan Roslansky called it, according to Business Insider. Younger workers are taking advantage of the labor shortage to upgrade their careers.

The Great Resignation that you’ve been hearing so much about is really a “Great Reshuffle.”

That’s according to LinkedIn CEO Ryan Roslansky in a recent interview with TIME. He said his team tracked the percentage of LinkedIn members (of which there are nearly 800 million) who changed the jobs listed in their profile and found that job transitions have increased by 54% year-over-year.

Younger workers are leading the way.

Gen Z’s job transitions have increased by 80% during that time frame, he said. Millennials are transitioning jobs at the second highest rate, up by 50%, with Gen X following at 31%. Boomers are trailing behind, up by just 5%.

Other research backs up the trend that the early- to mid-level employees quitting are seeking greener pastures in the form of a new job. In late July, a Bankrate survey found that nearly twice as many Gen Z and millennial workers than boomers planned to look for a new job in the coming year. In August, a study by Personal Capital and The Harris Poll found that two-thirds of Americans surveyed were keen to switch jobs. The majority of Gen Zers felt that way (91%), as did more than a quarter of millennials.

It’s at the transactional level, accounting operations, technology operations. Clients are more apt for them to want them to be on site. For the higher-level management resources, for tech developers, database administrators, they’re more inclined or more accepting of remote roles there. So it makes it easier for us with the latter than with the former. Candidates actually want a premium today if you want them to be on site. And many clients will pay that. Some won’t.

Creative destruction at work

In the face of widespread worker shortages, companies that thrive in the current environment will have to change their business models. To be sure, the latest NFIB survey was full of complaints from small business owners who are unable to hire qualified workers. If the problem was simply excessively supportive government support, the problem wouldn’t be worldwide. Instead, companies need to change their business models. It’s the free market process of creative destruction at work.

Business Insider documented the story of a Florida worker who applied to 60 entry-level jobs from employers who complained about finding qualified employees. He got exactly one interview. This is anecdotal evidence that many employers are used to better bargaining power and they haven’t adjusted their expectations in accordance to changing conditions.

Two weeks and 28 applications later, he had just nine email responses, one follow-up phone call, and one interview with a construction company that advertised a full-time job focused on site cleanup paying $10 an hour.

But Holz said the construction company instead tried to offer Florida’s minimum wage of $8.65 to start, even though the wage was scheduled to increase to $10 an hour on September 30. He added that it wanted full-time availability, while scheduling only part time until Holz gained seniority.

When large employers like Amazon have boosted the average starting wage to $18 per hour, some small employers with low-skilled workers won’t be able to compete at their current worker intensity levels. They will either have to adjust or go out of business. In addition, Amazon’s wage pledge will put upward pressure on manufacturing jobs, which pay more but reduce the skilled worker wage premium.

There are two obvious ways that companies can thrive in the current environment. The ones with already unionized workforces will enjoy a competitive advantage. Bloomberg documented the difference between United Parcel Service, which beat both EPS and sales expectations, and FedEx.

The company has weathered a labor shortage better than its key competitor because, unlike FedEx, it has a union workforce and pays the highest wages in the industry. Compensation and benefits rose only 0.6% in the quarter from a year ago.

“I feel really good about our ability to manage through the labor cost inflation that many companies are dealing with today,” Tome told analysts.

This is not to imply that unionizing a workforce is a quick fix for competitive problems as it is unclear how such transitions would affect a company’s business models and operating practices.

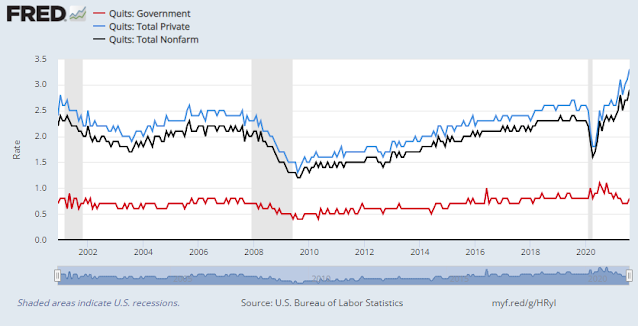

The FRED Blog pointed out that the quit rate between private sector and government workers has diverged dramatically since the pandemic. While government workers are not necessarily unionized, their HR relationship is more regimented and more union-like, and the workers are older. Nevertheless, this is one piece of evidence that a unionized or near-unionized will see greater turnover stability.

The other way to compete in an era of tight labor markets is to substitute capital for labor through automation. Core capital goods orders have been very strong in this cycle. They should maintain their strength in light of the tight labor market, which should spark a period of productive non-inflationary growth. On top of that, climate change initiatives will result in a surge of investment in new technologies and infrastructure.

The post-Black Death boom

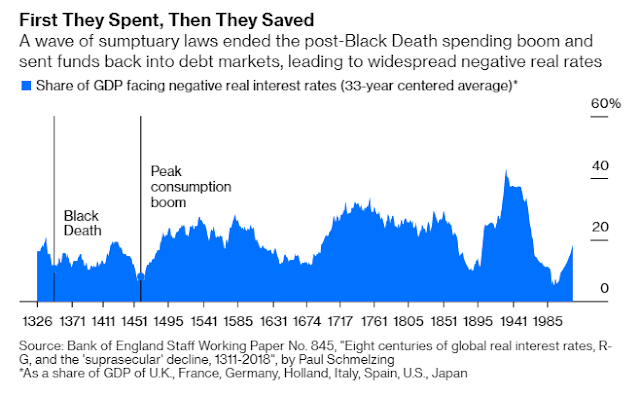

The recovery from the 2020 pandemic is likely to parallel the historical experience of past pandemics. While COVID-19 isn’t the Black Death, a Bloomberg article outlined the economic effects of the Black Death during the second half of the 14th Century. As the epidemic killed off nearly 60% of Europe’s population, real wages rose.

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme. The recovery from the Black Death sparked a re-focus on personal satisfaction and consumption boom. Sound familiar?

The change in behavior was more stark. “The Black Death created not just the means for wider parts of the population for excessive consumption – but the traumatizing experience of sudden decimation in the earthly life also triggered the impetus to enjoy it to the fullest, while still able to,” Schmelzing notes.

Products that hadn’t been for mass consumption earlier — such as linen underwear and glass panes in windows — became more widely available as cheap capital rushed to satiate the growing desire to consume, according to “Freedom and Growth,” historian Stephan Epstein’s review of states and markets in Europe between 1300 and 1750. Sumptuary laws that, among other things, sought to limit the height of Venetian women’s platform shoes were the state’s way to rein in conspicuous consumption; eventually the mad spending ended and savings went to bond markets. A republican ethos was born.

The spending boom kicked off a virtuous growth cycle. It began with a spending boom, which the economy recycled into greater savings and pushed interest rates lower.

Today’s post-COVID economy is undergoing a spending boom characterized by excess demand, which has strained supply chains. The next phase of the recovery should see inflation ease and higher investment spending and higher productivity. In other words, don’t worry about labor shortages or inflationary pressures. Barring unforeseen exogenous events, the next few years should have a boom in the global economy.

I recent read a research report that charts labor by deducting the Quit Rate from the Unemployment Rate. Is shows a very strong labor environment comparable to times when the Unemployment Rate was much lower.

Expectations of higher wages will spur spending. I’ve always thought the Feds theory that high inflation expectations would drive demand is only true with housing. Everything else is driven more by higher wage expectations. When people expect higher wages, they change their lifestyles plus they might borrow to get things sooner with the expectation higher incomes will pay back he loan.

Emerging stock markets are a mess, especially Brazil, one of the largest. The Far East is also down. India was he only big winner but the last two weeks has seen it fall sharply 5%. Could be Covid related. I’m surprised Developed Markets haven’t felt any pressure from this stock weakness. The international companies have big global sales.

It’s about time workers had more leverage. The shift towards a better work life balance is a good thing. Too much money has been concentrated at the top for too long. Overall, this will be very positive for the economy I think, as people can spend more and be healthier in mind and body.

Hear Hear

Well said!

But does it mean for investors that central banks will scale back their liquidity injections? Amazon (or their shares) are generally rewarded by investors for investing cash into their business instead of paying out dividends. The megacap tech corporations have access to ample amount of funding at very low rates, Amazon does not have to be profitable, they will be able to compete for a shrinking workforce much longer than anybody else. All they want to do is grow and if that means paying higher wages it is going to happen. By making financing conditions so benign, has a wage-increase spiral been set into motion by those corporations that can leverage und use the system to their advantage (it is more difficult for companies that can not issue corporate bonds, a recent DB research paper highlighted how America’s banks prefer funnelling liquidity back into the domestic bond market rather than extending credit or giving out loans)

Personally, I think a pullback in equities is around the corner, one which may be catalyzed by a move toward tightening by the Fed.

I would welcome an increase in interest rates for multiple reasons.

(a) An increase in bond yields that makes fixed income an attractive alternative to stocks.

(b) A much-needed correction in real estate prices, especially in the Bay Area. Our youngest son is in college and we would jump on any opportunity to help him purchase a home nearby.

(c) We plan to begin laddering into Series I bonds next week, and hope to see rates revert to the mean over the next 15-20 years. As I opined earlier – an attractive alternative to self-insure future LTC/health care needs.

The time for low rates is over.

The Bay area is a vacuum cleaner for jobs. History suggests there will be continual population growth in the area causing further rise in real estate prices.

If the US stock market keeps going higher, Bay area RE prices will keep going higher.

https://www.yahoo.com/finance/m/a3f809b2-40be-3622-b232-3031765afcfa/home-prices-rose-19-8-in.html

Banks are flush with liquidity. White collar jobs in the Bay area commanding even higher compensation.

While the post black death era of spending and higher growth rates is a good analogy, post WW2 economic revival is another from recent times. I think we are in for a fairly long period of economic growth. Such growth will be lead by AI/Automation/tech leading to even greater loss of blue collar workers. Automobile industry is a good example. Conventional auto repair jobs, sales jobs in automobiles, truck drivers come to mind, as being on marked time. Capital will be required to power such growth (from the central banks).

Overseas markets are a good example where chip industry is likely to see some upheaval and supply chains moving away from China.

Demand for capital will continue to rise globally causing rates to rise in the 5-7 year maturity. Yield curve (2-10) may steepen.

https://www.yahoo.com/finance/news/bond-rates-inflation-hedge-why-162440071.html

These are not the rates one gets over the next 30 years.

https://www.yahoo.com/finance/news/expected-cuts-treasury-auctions-may-155356045.html

The move, which is well anticipated on Wall Street, will likely total an $800 billion cut in nominal auction sizes in the 2022 fiscal year compared with the 2021 fiscal year, according to estimates from NatWest. The majority of those cuts will come in securities with a 7-year duration or less, with a $2 billion per month cut in Treasury bonds with durations of 2, 3, and 5 years, and $3 billion per month cuts in 7, 10, and 20-year Treasuries, the bank estimates.

The above would flatten the yield curve based on the skew of reduced purchases which is greater at the longer end of the curve. Interesting. The whole yield curve should come down (?) or may be just a wash?