Preface: Explaining our market timing models

We maintain several market timing models, each with differing time horizons. The “Ultimate Market Timing Model” is a long-term market timing model based on the research outlined in our post, Building the ultimate market timing model. This model tends to generate only a handful of signals each decade.

The Trend Model is an asset allocation model which applies trend following principles based on the inputs of global stock and commodity price. This model has a shorter time horizon and tends to turn over about 4-6 times a year. In essence, it seeks to answer the question, “Is the trend in the global economy expansion (bullish) or contraction (bearish)?”

My inner trader uses a trading model, which is a blend of price momentum (is the Trend Model becoming more bullish, or bearish?) and overbought/oversold extremes (don’t buy if the trend is overbought, and vice versa). Subscribers receive real-time alerts of model changes, and a hypothetical trading record of the those email alerts are updated weekly here. The hypothetical trading record of the trading model of the real-time alerts that began in March 2016 is shown below.

The latest signals of each model are as follows:

- Ultimate market timing model: Buy equities

- Trend Model signal: Neutral

- Trading model: Neutral

Update schedule: I generally update model readings on my site on weekends and tweet mid-week observations at @humblestudent. Subscribers receive real-time alerts of trading model changes, and a hypothetical trading record of the those email alerts is shown here.

A framework for Sino-American relations

The anticipation is over. The Trump-Xi summit is done. Did you think that things would be so easy, and everything could be solved in a single meeting?

The market came into weekend knowing that there was a high degree of uncertainty surrounding the summit, but the consensus was both sides would agree to a trade truce. Mytrade war factor, which measures the relative performance of companies with pure domestic revenues, was complacent about the prospects of a trade war.

The option market behaved in a similar way. The ratio of 9-day implied volatility (VXST) to one-month volatility (VIX) exhibited only mild signs of anxiety, and levels were not high compared to recent history.

The market was indeed fortunate that the outcome was slightly better than market expectations. Not only did both sides agree to a truce while discussions continue, and Trump has lifted a temporary ban on on American companies selling equipment to Huawei.

Notwithstanding the short-term results from the summit, here are some issues that investors and policy makers should think about in terms of the future Sino-American relations.

- If this is a war, what costs is America willing to bear?

- Is this a trade war, or something more?

- How much support can the Fed offer, and what are the implications of the Fed’s actions?

In the absence of trade war risk, the intermediate-term equity outlook is bullish. There is no signs of a recession on the horizon. The Fed has signaled that it stands ready to “act as appropriate to sustain the expansion”. There is little more that the bulls could ask for.

The costs to America

If this is a war, sacrifices will have to be made. What costs are Americans willing to bear? A simple framework offered by Jason Furman is the cost-benefit analysis in a Twitter thread.

Chris Balding recently wrote a thoughtful post entitled “How Should We Think About the Costs Associated with Challenging China?” in which he distinguished between positive and negative costs:

We need to distinguish between positive and negative costs. By positive cost I mean a transaction where money is spent and a tangible good, service, or investment is received in return. Think of R&D, where money is expended and there is a tangible activity that is paid for with money in the expectation it produces a tangible intellectual property asset. A negative cost is a transaction where there is a less direct line between money spent or foregone and the expected return. Think for instance of imprisoning a robber. There is no tangible investment made though a cost is incurred but the expectation is that incarceration will correct behavior. Positive costs expect to produce positive outcomes via greater goods while negative costs hope to produce positive outcomes via reduction in negative events, outcomes, or costs.

There is a consensus for incurring positive costs, such as infrastructure spending, as a way to challenge China:

To address how best to deal with China, many people across the partisan aisle, are almost excited to incur positive costs. What is the old saying about politics, never let a good crisis go to waste. Consequently, everyone has news ways to spend money that frequently require tortured logic of how best to deal with China but still channels money to their preferred project. Building out the Acela from DC to Boston may or may not be a good idea, I personal think it is not, but it is difficult to see how producing one high speed rail line will stand up to China, especially on the cost to benefit ratio. This does not even necessarily mean that the project is bad as a stand alone project, however, especially under a budget constraint, a little discernment is called for about how best to challenge or compete with China.

The challenge is agreeing on incurring negative costs:

Where most people begin to get uncomfortable is when they are asked to bear negative costs associated with challenging China. This is a thorny topic for a couple of reasons. First, while positive costs distribute funding they also impose little direct cost given the use of sovereign debt market to fund most of the increased spending (assuming there is no offsetting tax increase). Second, there is very little way to predict what all the negative costs will be. Third, while benefits tend to widely shared, costs are borne by very narrow discrete groups or people making them much more vocal. With all those caveats let’s still try and explore what negative costs we should be considering.

Examples of negative costs are the proposed on Huawei and other Chinese suppliers, which have created hardship for rural telecom providers that are suddenly faced with the expense of replacing their Huawei telecom equipment.

Another example is the growing suspicion and scrutiny of ethnic Chinese scholars in American research institutions. The atmosphere has become so poisoned that the president of MIT wrote the following open letter in support, not only of Chinese researchers, but talented immigration in general:

To the members of the MIT community,

MIT has flourished, like the United States itself, because it has been a magnet for the world’s finest talent, a global laboratory where people from every culture and background inspire each other and invent the future, together.

Today, I feel compelled to share my dismay about some circumstances painfully relevant to our fellow MIT community members of Chinese descent. And I believe that because we treasure them as friends and colleagues, their situation and its larger national context should concern us all.

The situation

As the US and China have struggled with rising tensions, the US government has raised serious concerns about incidents of alleged academic espionage conducted by individuals through what is widely understood as a systematic effort of the Chinese government to acquire high-tech IP.As head of an institute that includes MIT Lincoln Laboratory, I could not take national security more seriously. I am well aware of the risks of academic espionage, and MIT has established prudent policies to protect against such breaches.

But in managing these risks, we must take great care not to create a toxic atmosphere of unfounded suspicion and fear. Looking at cases across the nation, small numbers of researchers of Chinese background may indeed have acted in bad faith, but they are the exception and very far from the rule. Yet faculty members, post-docs, research staff and students tell me that, in their dealings with government agencies, they now feel unfairly scrutinized, stigmatized and on edge – because of their Chinese ethnicity alone.

Nothing could be further from – or more corrosive to – our community’s collaborative strength and open-hearted ideals. To hear such reports from Chinese and Chinese-American colleagues is heartbreaking. As scholars, teachers, mentors, inventors and entrepreneurs, they have been not only exemplary members of our community but exceptional contributors to American society. I am deeply troubled that they feel themselves repaid with generalized mistrust and disrespect.

The signal to the world

For those of us who know firsthand the immense value of MIT’s global community and of the free flow of scientific ideas, it is important to understand the distress of these colleagues as part of an increasingly loud signal the US is sending to the world.Protracted visa delays. Harsh rhetoric against most immigrants and a range of other groups, because of religion, race, ethnicity or national origin. Together, such actions and policies have turned the volume all the way up on the message that the US is closing the door – that we no longer seek to be a magnet for the world’s most driven and creative individuals. I believe this message is not consistent with how America has succeeded. I am certain it is not how the Institute has succeeded. And we should expect it to have serious long-term costs for the nation and for MIT.

For the record, let me say with warmth and enthusiasm to every member of MIT’s intensely global community: We are glad, proud and fortunate to have you with us! To our alumni around the world: We remain one community, united by our shared values and ideals! And to all the rising talent out there: If you are passionate about making a better world, and if you dream of joining our community, we welcome your creativity, we welcome your unstoppable energy and aspiration – and we hope you can find a way to join us.

“Researching while Asian” is becoming the new “driving while black”. The Economist rhetorically asked if the US is losing its appeal to brainy foreigners (and not just the Chinese):

America—like every advanced economy—increasingly needs to attract the most highly educated talent possible. The high-skilled, who tend to congregate with other high-skilled people, usually in cities and universities, are more likely to be wealth creators, in finance or creative industries and well-placed to exploit new technology. Entrepreneurs, university graduates and others with demonstrable talent are in high demand. How a country attracts and keeps the highest-skilled migrants, therefore, is a measure of its likely future strength.

Historically, America has far exceeded rival countries in appealing to brainy foreigners and putting them to work, for example in how it gets foreigners into employment after they graduate from its universities. But under Mr Trump that crown is slipping.

Take a look at a typical ranking of the top universities around the world, and most of them are American. Education has historically been America`s competitive advantage, but many of the scholars at US schools are not native born. The US is increasingly making it difficult for American schools to admit talented foreign students.

The OECD, a think-tank for mostly rich countries, this week spelled out America’s problem. In pure terms of attractiveness to the high-skilled around the world, the authors of a new report say that America still ranks as the most popular place. Across seven indicators the think-tank studied for its measure of “talent attractiveness”–including unemployment levels, tax rates, gender equality, how easy it is for the family of a talented individual to settle and more—America still stands out as the most tempting destination for the brainy.

But on a second set of indicators the country fares worse. These include whether an applicant is likely to be denied a visa, how tight quotas are for the highly skilled, and the time and hassle involved in getting an application processed. Count in those considerations and America’s appeal to the most talented international workers falls sharply. The OECD ranks America behind several other rich countries, including Australia, Sweden, Switzerland, New Zealand, Canada and Ireland.

Measuring the AI race

What about crucial technologies like artificial intelligence? Isn’t China catching up quickly?

MacroPolo analyzed AI research and talent to cut through a lot of myths about the US-China rivalry in AI research, and the results are revealing. When they compared the top 1% of AI research talent, while there was a significant minority that came from China, the majority of researchers are affiliated with American universities.

Of the top 20% of AI researchers, about one-quarter come from China. However, the majority of them gravitate to the US to work or study.

This illustrates the strength of America’s competitive advantage in a leading edge topic like AI research. There is a clustering effect of top researchers at work. Elite researchers want to live and work in places where they can interact with other leading lights in their field.

These examples illustrate the extent of the “negative costs” that are borne by very specific groups. In the case of the heightened scrutiny of Chinese scholars and researchers, these measures erode America’s long-term competitiveness. This Bloomberg article about how the FBI is purging Chinese scientists from cancer research, which is a basic science, illustrates my point about how American competitiveness will be hobbled in the future. Instead of attracting top talent to America, they might migrate to some of the other countries identified by the OECD.

A trade war, or something more?

Another consideration that Trump and other American policy makers will have to decide on is whether the conflict with China is just a trade war, or a strategic competition that was outlined in the 2017 National Security Strategy.

If the dispute is purely a trade war, former American trade negotiator Wendy Cutler suggested that common ground can be found if there is sufficient political will. As an example, she cites the difference between the Chinese demand of lifting all tariffs as part of an agreement, compared to the American position of keeping tariffs in place until China implements its commitments under any treaty:

The current score card consists of $250 billion of Chinese imports and $110 billion of U.S. imports facing tariffs as high as 25%. China wants all of these tariffs lifted; the U.S. wants them to stay in place until China demonstrates a solid record of implementation. One solution would be to keep in place only the first tranche of U.S. tariffs hikes applied to $50 billion of imports, with a clear timeline for the remaining tariffs to be lifted tied to implementation bench marks. The U.S. could argue that these tariffs were specifically designed to hit those Chinese products benefiting from lax Chinese intellectual property practices, unlike the remaining $200 billion. China could point to its success in getting the U.S. to lift the bulk of the tariffs, while pointing to a path for removing the rest.

Another key sticking point is China’s demand for balance, or equality in a trade treaty:

Given the huge bilateral imbalances and Chinese unfair trade practices, it is only natural the U.S. believes the talks must focus on Chinese obligations. China, on the other hand, has a deep-seated disdain for “unequal treaties,” and is insisting that any deal include U.S. commitments. The key to addressing the issue may be the optics. Instead of phrasing commitments as applying solely to China, language for certain obligations can easily apply to both without the U.S. having to do anything. For example, since the U.S. has a strong intellectual property protection regime, it could easily agree that obligations in this chapter apply to it as well. This would allow China to claim the deal is two-way.

These are just a couple of examples of how negotiators could bridge seemingly intractable gaps in respective positions. A trade agreement is possible if the political will is there.

On the other hand, if the dispute is a strategic competition, what are the foreign policy dimensions to the conflict?

Some of Trump’s foreign policy signals have been highly confusing and contradictory. On one hand, the US has approved the sale of an arms package to Taiwan, which China regards as a renegade province and unwarranted interference with internal affairs. Similarly, US support for the protesters in Hong Kong is not winning them any friends in Beijing.

On the other hand, Trump tweeted last week that

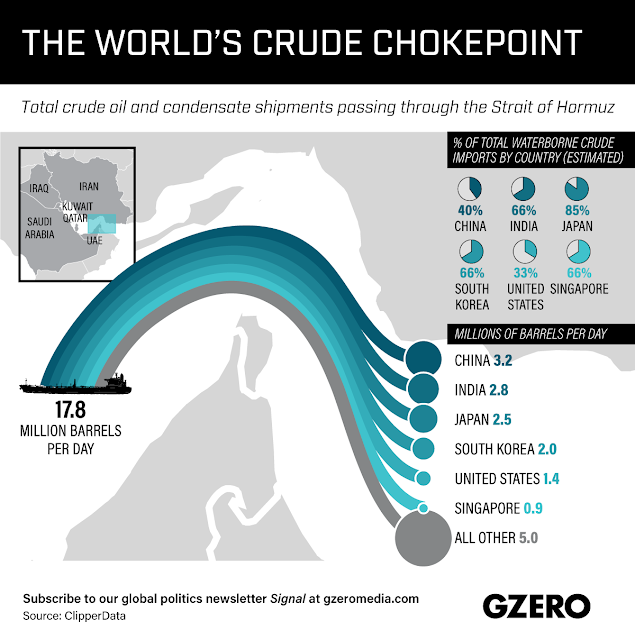

China gets 91% of its Oil from the Straight, Japan 62%, & many other countries likewise. So why are we protecting the shipping lanes for other countries (many years) for zero compensation. All of these countries should be protecting their own ships on what has always been….

….a dangerous journey. We don’t even need to be there in that the U.S. has just become (by far) the largest producer of Energy anywhere in the world! The U.S. request for Iran is very simple – No Nuclear Weapons and No Further Sponsoring of Terror!

Notwithstanding the spelling mistake (“strait” instead of “straight”) and inaccuracies about the percentage of oil China receives from the Middle East, is he announcing a policy of American withdrawal from the region, and asking for others to step in? Is he inviting the People’s Liberation Army Navy to guarantee the security of oil tankers in the Gulf? Does he realize that such a decision implicitly cede regional security throughout South Asia and the South China Sea to the PLA Navy?

A supportive Fed?

For investors, another variable to consider is Fed policy. The market has fully discounted at least a quarter-point rate cut at the July FOMC meeting, with a 22% chance of a half-point cut. Analysis from Bianco Research reveals the probability of market disappointment falls rapidly as we approach the date of the meeting. Since we are just beyond the 30 day window in the chart, a rough estimate of a July rate cut stands at about 75%.

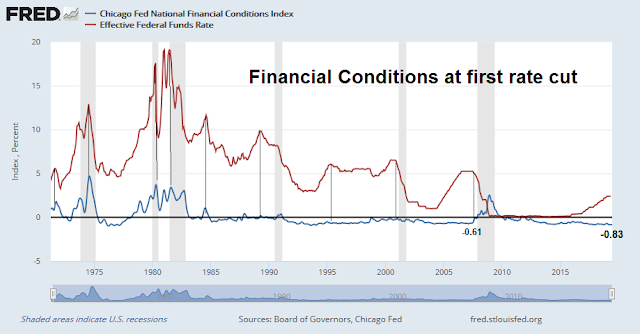

Should the Fed choose to cut rates at its July meeting, it will have achieve the unusual milestone of initiating an interest rate reduction cycle when financial conditions are looser than any time in the history of the Chicago Fed’s National Financial Condition Index.

What will the Fed do? Chairman Powell has made it clear that he is concerned about global economic weakness and trade tensions as sources of instability. In the event of a trade war, he will do everything he can to support economic growth.

On the other hand, what happens in the case of a long drawn-out trade truce? There are some clues from Powell’s latest speech on June 25, 2019. He reiterated his concerns about trade, the global economy, and the loss of business confidence putting the brakes on capital expenditures:

The crosscurrents have reemerged, with apparent progress on trade turning to greater uncertainty and with incoming data raising renewed concerns about the strength of the global economy. Our contacts in business and agriculture report heightened concerns over trade developments. These concerns may have contributed to the drop in business confidence in some recent surveys and may be starting to show through to incoming data. For example, the limited available evidence we have suggests that investment by businesses has slowed from the pace earlier in the year.

Powell reiterated “the Committee will closely monitor the implications of incoming information for the economic outlook and will act as appropriate to sustain the expansion”. The phrase “act as appropriate to sustain the expansion” translates to at a July cut, but investors expecting three quarter-point rate cuts in 2019 might be disappointed because of the Fed’s data dependency. Even St. Louis Fed president James Bullard, who is one of the most dovish members of the FOMC, recently told Bloomberg TV that while he dissented at the June meeting and argued for a 25 basis point insurance cut, a 50 basis point cut would be overdone.

Another variable to consider that is related to Fed policy is the US Dollar. Trump has managed to drag the Dollar into the agenda at the G-20 by complaining about the strength of the greenback. Everything else being equal, an accommodative Fed will tend to weaken the USD. Indeed, the history of the spread between US and eurozone rates has been astounding. The recent signals of Fed easing has begun to weaken the USD, and there is a lot of room for the spread to narrow.

Market implications

A Fed decision to make an about-face to switch to an easy money policy would be very bullish for risky assets. Troy Bombardia detailed past instances when the stock market rallied at least 15% over the past six months and the Fed cut rates. If history is any guide, the odds lean bullish.

Moreover, falling US rates puts downward pressure on the USD. This would relieve any pressure on EM economies under stress, which is another factor supportive of a risk-on environment.

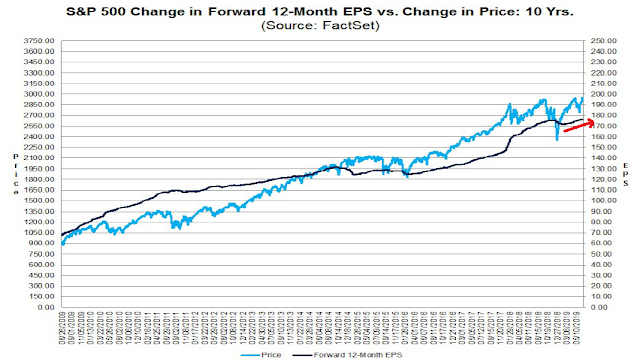

As we approach Q2 earnings season, FactSet reports that earnings estimates continue to rise, indicating positive fundamental momentum. This should be supportive of stock prices, in the absence of a renewed trade war.

The macro outlook is best summarized by New Deal democrat as a dilemma of two time frames:

It boils down to: the short term forecast — over the next 4 to 8 months — looks flat at best, and could develop into an actual downturn. The longer term — over one year out — looks more positive…

In short, short leading indicators have been going basically sideways. And as I’ve noted repeatedly in the last few months, the leading employment sectors of manufacturing, residential construction, and temp jobs have all turned flat or downward since January. Whether there’s a recession or not in the short term probably depends on the intensity of Trump’s trade wars, and how much businesses, and business planning, suffers for them.

In the absence of trade war risk, the intermediate-term equity outlook is bullish. There is no signs of a recession on the horizon. The Fed has signaled that it stands ready to “act as appropriate to sustain the expansion”. There is little more that the bulls could ask for.

The week ahead

Up until now, all of the technical analysis and sentiment analysis leading up to the G-20 summit had only marginal value, because of the binary nature of the meeting outcome. I would expect that the stock market would adopt a risk-on tone on Monday and gap up.

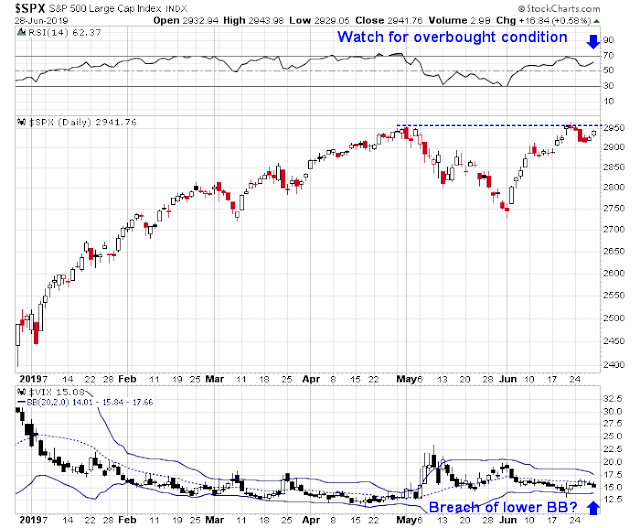

How far up? Here is where technical and fundamental analysis can provide some guidance. Assuming that the S&P 500 breaks out to new all-time highs on Monday, here is what I would watch for signs of a possible stall.

- An overbought signal on the 14-day RSI would provide the first warning sign, though overbought markets can become even more overbought.

- A VIX close below its lower Bollinger Bnd can be another signal that the market may be losing momentum. A high degree of caution is warranted.

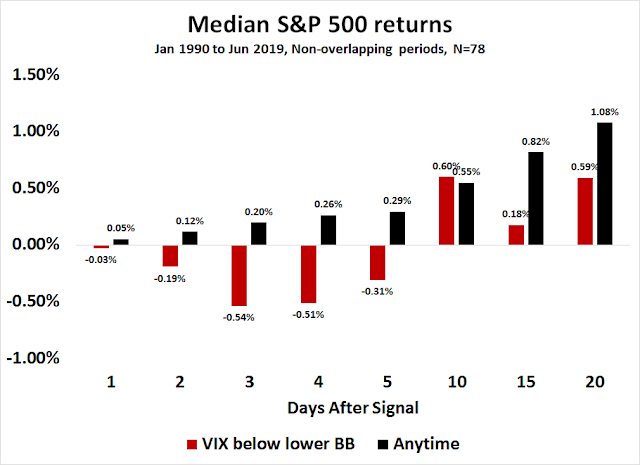

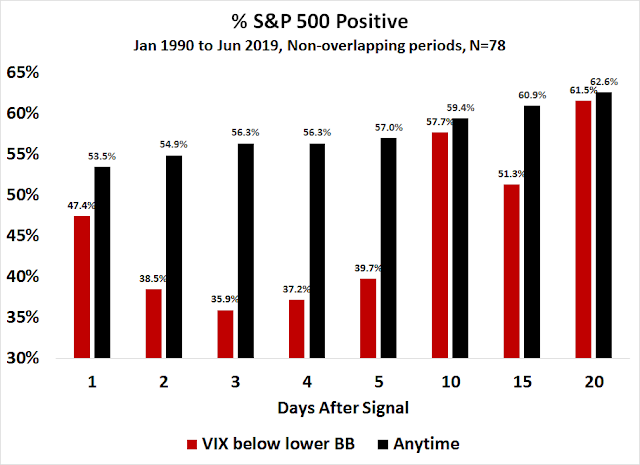

I made a study of all non-overlapping signals when the VIX fell below its lower BB, and the market returns have historically been poor in the first week after the signal, but began to climb again afterwards.

The same study of the success rate told roughly the same story. Returns were subpar in the first week and then recovered afterwards.

Aggressive traders could choose to buy the initial surge, but be prepared for a pullback. The market is likely to become overbought and stall within the first week. In addition, there may be bearish triggers in mid-July.

Robert Mueller is scheduled to testify before the House Intelligence and Judiciary committees on July 17, and those events are likely to unnerve Trump. President Trump is a master of the media, and he has shown a pattern of reverting to the unexpected exercise of powers in border security and trade to deflect attention from political threats. The last example was his directive to slap a 5% tariff on Mexico if the migrant problem was not solved. Don’t be surprised if Trump lashes out at European autos, or uses either of his NAFTA partners as punching bags again around the time of the Mueller testimony.

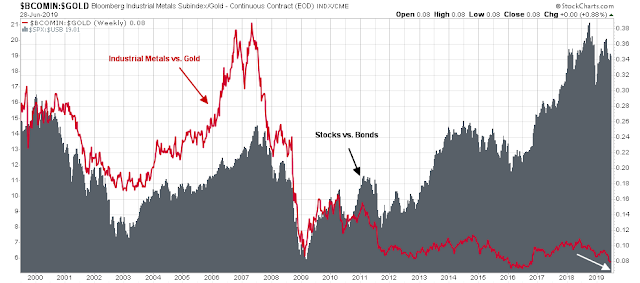

Once the rally starts to roll, I would monitor the performance of cyclical stocks for a market signal to the sustainability of the move. Undoubtedly, semiconductors will perform well in light of Huawei’s temporary reprieve, but what about the other cyclical groups?

Another way of measuring a cyclical reflationary effect is the ratio of industrial metals to gold. While both are commodities and both have inflation hedge characteristics, industrial metals are more sensitive to global growth, and the industrial metals to gold ratio is historically correlated to the stock to bond ratio, which is an indicator of risk appetite.

That said, how far can stock prices rise under a best case scenario of no trade war, a supportive Fed, and continued growth?

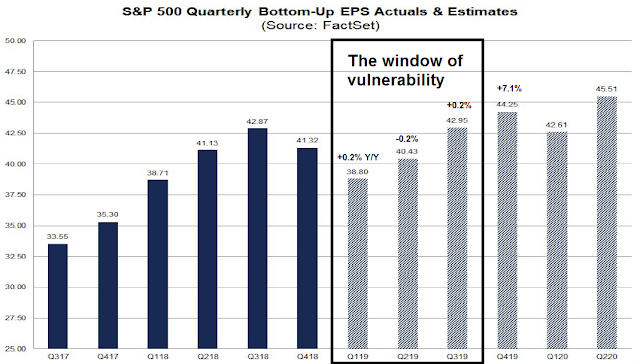

Let us begin with the growth outlook. FactSet reports that expected year/year quarterly EPS growth is expected to be soft until Q4. Should we sail past this window of vulnerability without a trade war, the outlook should begin to turn up late in the year.

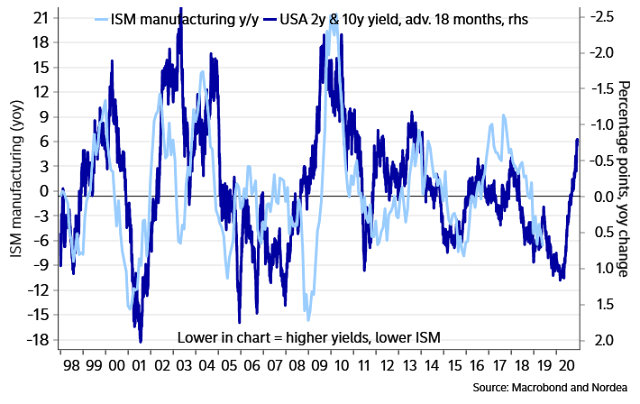

Analysis from Nordea Markets tells a similar story. Surveys like ISM and PMI are short leading indicators, and the yield curve is a long leading indicator. It is therefore no surprise that the yield curve leads ISM readings. Based on this analysis, the economy should bottom out and turn up either Q4 2019 or Q1 2020.

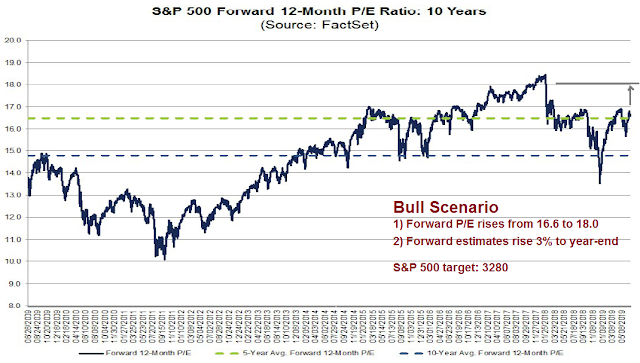

So where does that leave equity investors? Let us try some rough back of the envelope calculations. The forward P/E of the market stands at 16.6. Supposing exuberance took over because of the lack of trade war tail-risk, and forward P/E rises to 18.0. Add another 3% to increase to forward earnings to year-end. The combination of P/E expansion and rising earnings gives us an approximate year-end target of 3280, or 11.4% plus dividends from Friday’s close.

From a technical perspective, the outlook appears even more bullish. The market is likely to stage a decisive upside breakout next week, and the upside target on the point and figure chart ranges from 3750 to 4100, depending how the parameters are defined. I would caution, however, that the time frame for point and figure target is likely to be longer than the fundamentally derived target in the previous exercise.

In conclusion, the intermediate-term outlook equity outlook appears bullish, and may be poised for a melt-up. Be prepared for short-term pullbacks. Since the US and China only agreed to restart talks, an agreement is no slam dunk, and setbacks will be inevitable. Given what is at stake for both sides, weakness should be regarded as buying opportunities as long as recession risk is low.

My inner investor was neutrally positioned at roughly his asset allocation target weights coming into the weekend. He will be opportunistically raising his equity weight in the days and weeks to come.

My inner trader was in all cash coming into the weekend as he did not want to flip a coin on the summit outcome. He expect to take an initial long position on Monday.

We may see something stunning this week after the trace truce at the G20 on the weekend. The Fed Funds futures could rise a surprising amount. A Fed Funds cut in July is baked in but Powell has underlined trade as a key factor in deciding future cuts. Will futures traders believe fewer cuts will happen now that a trade war has been walked back? Did traders take the futures contract too far and now it might snap back due to panic selling?

In December the market was panicking because investors fears the higher rates the Fed promised would cause a recession. Then the Fed turned dovish and the markets celebrated. Did the futures market and investors in general go to far, further than the Fed was heading?

A big swing up in Fed Funds futures interest rates will hurt bond markets and the defensive areas of the stock market. The higher the rate outlook goes, the bigger the pressure.

Of course, if markets just feel the weekend pause is nothing much, then there will be little movement. But I believe one should be prepared and know what to watch. Here is a chart that updates nightly;

https://product.datastream.com/dscharting/gateway.aspx?guid=b7ec9234-f31b-4931-89e1-1040262ad80a&action=REFRESH

The S&P 500 might have growth stocks going up sharply due to less trade worries while defensive stocks fall since defensives are negatively influenced by higher rates. This would lead to less movement on this index than on the NASDAQ.

if Fed fund futures start rising, this would also be negative for USD and supportive for commodities and EM markets?

I quote from Ken, above;

“Did traders take the futures contract too far and now it might snap back due to panic selling”?

A panic sell off in Fed funds price, will mean (implied) fed funds rate rise, as futures prices fall.

If I read your missive correctly, here, Fed fund prices in the futures markets could fall (not rise), is what you are saying, if the traders stop believing multiple rate cuts down the year.

It is entirely possible that we get a hawkish cut, but that won’t happen until the FOMC meeting at month-end.

Looks like Huawei is not getting any reprieve. U.S. government staff told to treat Huawei as blacklisted.

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-usa-huawei/u-s-government-staff-told-to-treat-huawei-as-blacklisted-idUSKCN1TY07N