Preface: Explaining our market timing models

We maintain several market timing models, each with differing time horizons. The “Ultimate Market Timing Model” is a long-term market timing model based on the research outlined in our post, Building the ultimate market timing model. This model tends to generate only a handful of signals each decade.

The Trend Model is an asset allocation model which applies trend following principles based on the inputs of global stock and commodity price. This model has a shorter time horizon and tends to turn over about 4-6 times a year. In essence, it seeks to answer the question, “Is the trend in the global economy expansion (bullish) or contraction (bearish)?”

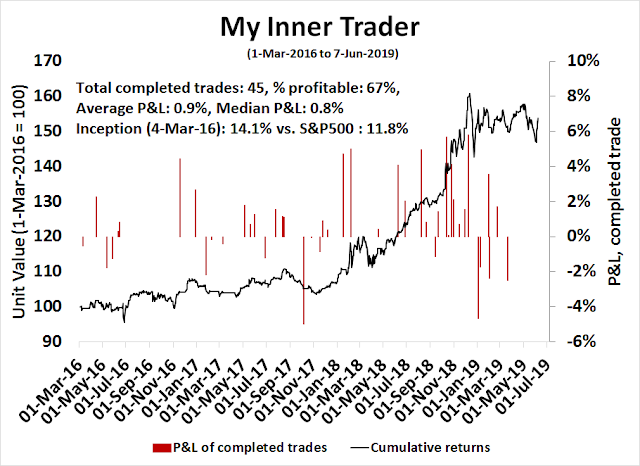

My inner trader uses a trading model, which is a blend of price momentum (is the Trend Model becoming more bullish, or bearish?) and overbought/oversold extremes (don’t buy if the trend is overbought, and vice versa). Subscribers receive real-time alerts of model changes, and a hypothetical trading record of the those email alerts are updated weekly here. The hypothetical trading record of the trading model of the real-time alerts that began in March 2016 is shown below.

The latest signals of each model are as follows:

- Ultimate market timing model: Buy equities

- Trend Model signal: Neutral

- Trading model: Bullish

Update schedule: I generally update model readings on my site on weekends and tweet mid-week observations at @humblestudent. Subscribers receive real-time alerts of trading model changes, and a hypothetical trading record of the those email alerts is shown here.

Tariff Man and Dow Man gang up on the Fed

David Rosenberg advanced an intriguing theory last week. Could Trump be weakening the economy sufficiently for the Fed to cut rates, and then call off the trade war so that the stock market could soar ahead of the 2020 election?

Viewed in the context of Jerome Powell’s remarks at a Fed policy conference last week which acknowledged trade tension risks, that scenario is a possibility.

I’d like first to say a word about recent developments involving trade negotiations and other matters. We do not know how or when these issues will be resolved. We are closely monitoring the implications of these developments for the U.S. economic outlook and, as always, we will act as appropriate to sustain the expansion, with a strong labor market and inflation near our symmetric 2 percent objective. My comments today, like this conference, will focus on longer-run issues that will remain even as the issues of the moment evolve.

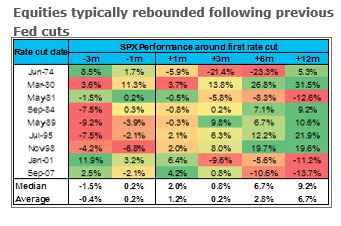

Will the Fed play ball? The market is now discounting three rate cuts by year-end, with the first one at the July FOMC meeting. This matters to equity investors. A historical study from Barclays showed that the stock market tends to have a strong positive reaction a month after the first rate cut, and returns were even stronger after six months.

I leave the conclusion to Fed watcher Tim Duy, who puts it much better than I could ever do:

Although the stage is set for the Fed to cut rates, policy makers won’t have sufficient data to act until the end of the summer. A move at the September meeting is a reasonable baseline at this point. If the data deteriorate more quickly, or if markets seize up, pull that cut forward into July. If trade tensions ease and growth stays strong, push it back.

Will the on again, off again trade tensions drag on until Q3 or Q4? If so, expect a choppy range-bound and headline-driven market until the end of the summer and into the fall.

A softening economy

Here are some reasons why the Fed might cut rates. First, the economy is starting to soften. The latest miss on the May Non-Farm Payroll report was a negative surprise. The downward revisions to employment in March and April were also disappointing.

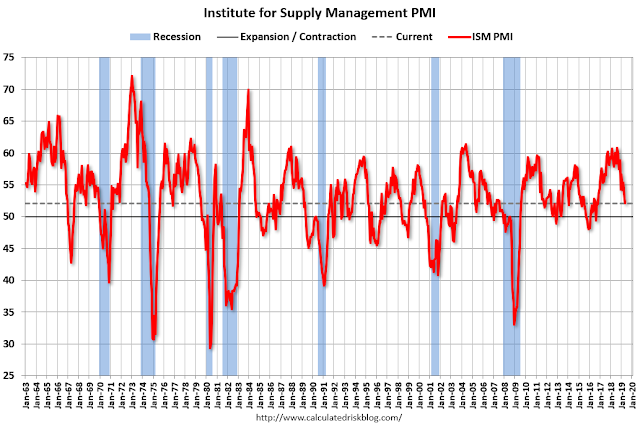

The latest ISM Manufacturing PMI fell and missed expectations, though ISM Services did rise and beat.

However, both IHS Markit’s US Manufacturing and Services PMI weakened, and missed expectations. The Composite PMI is now consistent with GDP growth decelerating to about 1%.

The Atlanta Fed’s nowcast of Q2 GDP growth is 1.5%, which is consistent the New York Fed’s nowcast at 1.48%. If Q2 GDP does come in at about 1.5%, this would represent a severe deceleration from the Q1 GDP growth rate of 3.2%,

Trade war jitters

The market reaction to the trade war has followed the script of past unexpected macro shocks. At first, investors only know the direction of the shock, but cannot accurately estimate the magnitude. Consequently, the only investment factors to matter are the technical analysis factors, because price reacts quickly to news. Strategists then begin to either revise their estimates, or build a range of scenarios with differing estimates. This is followed by earnings estimate revisions by company analysts, once they can quantify the magnitude of the disruption. This template has been followed by positive shocks, such as the last round of Republican tax cuts, and the numerous negative shocks that have hit EM economies over the years.

We are now at the second stage, and strategists are beginning to issue top-down revisions to earnings and GDP growth. Bloomberg reported that both BAML and Citi have reduced their top-down earnings estimates:

Bank of America and Citigroup have lowered their U.S. corporate profit forecasts while pointing out the risk of a recession as trade tensions escalate.

Savita Subramanian, who heads the U.S. equity strategy team at BofA, cut her 2019 estimate for S&P 500 companies by $2 a share to $166, saying import tariffs are set to increase costs, hurting profits for American firms. Tobias Levkovich, chief U.S. equity strategist at Citi, trimmed his projection by the same amount, to $170 a share.

In a separate article, Bloomberg reported that Morgan Stanley is calling for a recession if the trade war isn’t resolved:

A recession could begin in as soon as nine months if President Donald Trump pushes to impose 25% tariffs on additional $300 billion of Chinese imports and China retaliates with its own countermeasures, according to Chetan Ahya, chief economist and global head of economics at Morgan Stanley.

The rift between the Trump administration and China has escalated as each side blames the other for the breakdown in talks. Over the weekend, Trump celebrated his trade policies and the recent move to impose tariffs on Mexican goods in response to illegal immigration.

While stocks have declined, investors are still overlooking the impact the trade war will have on the global macroeconomic outlook, Ahya wrote in a note on Sunday. Growth will suffer as costs increase, customer demand slows and companies reduce capital spending, he said.

As the negative effects of the tariffs become more apparent, it may be too late for political action, according to Ahya. Policies to ease the impact are likely to be too reactive and slow to take effect.

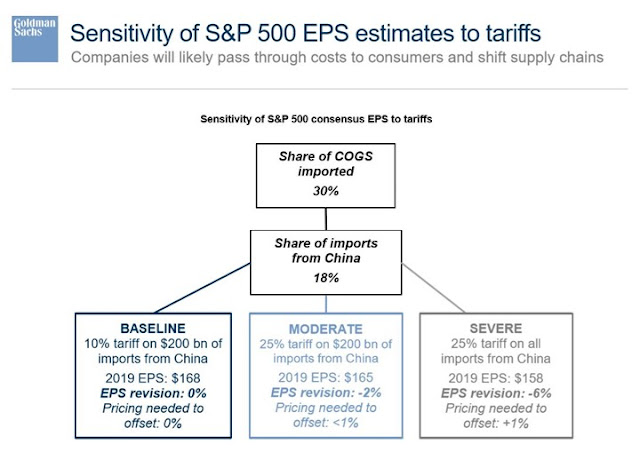

David Kostin at Goldman Sachs laid out several scenarios and estimated the impact of China tariffs to be as much as a 6% cut to 2019 earnings estimates.

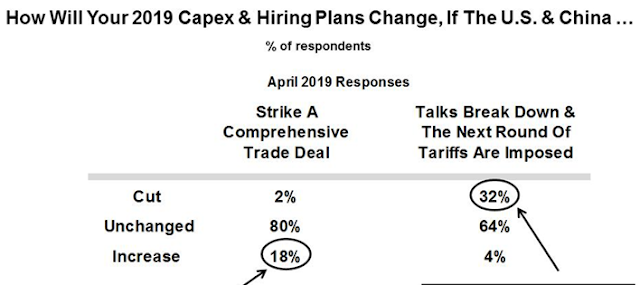

While analysts can estimate the direct first-order effects of tariffs and a trade war, it is far more difficult to estimate the second-order effects. How will these measures affect business and consumer confidence? A survey by Oscar Sloterbeck at Evercore revealed how a full-blown trade war might affect business confidence. 32% of US companies said that they would cut their capex plans if the US-China trade talks broke down.

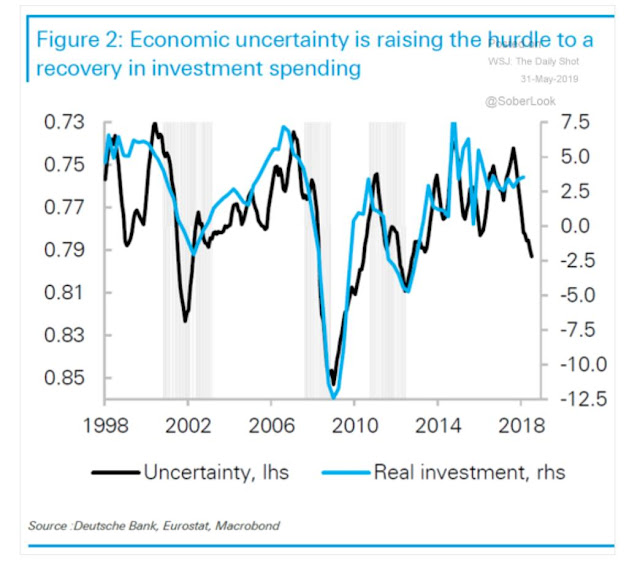

Deutsche Bank correlated the level of uncertainty with investment spending. The results are not pretty.

You can see why Powell said that the Fed is “monitoring the implications of these developments”. The Fed is clearly worried. The combination of a soft patch in growth and the rising tail-risk from trade wars has opened the door to rate cuts.

Market pressures

In addition, Powell has stated that the last two recessions have been caused by financial instability, and this is an important unspoken third mandate for the Fed. Consequently, I believe the Powell Fed is far more attuned to the market than either the Bernanke or Yellen Fed.

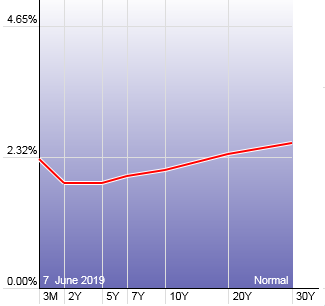

So how does the Fed interpret the message from the bond market? Not only is there a partial inversion, but most of the yield curve is under the Fed Funds target rate of 2.25% to 2.50%?

To be sure, there are limits to the Fed’s reaction function. Reuters reported that vice chair Richard Clarida said that the Fed can’t be handcuffed to the market.

The U.S. Federal Reserve will consider investors’ expectations when they weigh what to do with interest rates, but they will not be “handcuffed” to market prices, a central bank policymaker said on Tuesday.

“We’ll look at market pricing,” along with a range of data on how the economy is doing, Fed Board of Governors Vice Chair Richard Clarida told CNBC. “Market pricing can go up and down so we can’t be handcuffed to that.”

What’s the Fed’s reaction function?

How will the Fed react to these pressures? Will it cut rates?

For some perspective, policy makers do not use a seat-of-the pants decision process. They need a policy and decision making framework, or a model. The Fed may learn from the Bank of Canada. BNN-Bloomberg pointed out that the process to change a monetary policy framework can be excruciatingly slow:

Don’t bet on Federal Reserve officials to overhaul how they target inflation if the experience of counterparts at the Bank of Canada is anything to go by.

As Fed policy makers meet in Chicago to debate whether to change their inflation target, they have been sharing notes with counterparts north of the border where mandate reviews have been regularly undertaken over the past two decades.

The lesson they’ll learn is that the bar to change is high.

Every five years, the Bank of Canada reassesses its monetary policy guidelines, not unlike what the Fed is currently doing, including a conference this week on alternatives. While the research surrounding Canada’s reviews has been serious, the end result each time has only been minor changes.

The biggest tweak, made in 2011, gave the Bank of Canada more time to reach its target. The underlying objective — to focus exclusively on price stability and use 2 per cent inflation as an operational guide — has been largely untouched.

While the market has seized upon the changed tone of the latest Fedspeak, expectations for rate cuts may be premature. The party line has changed from “the economy is in a good place”, and “we will be patient”, to “the economy is in a good place”, but we are monitoring the situation. The term “patient” has been interpreted by the market as “we will neither raise nor lower rates”, while “monitoring the situation” is viewed as “we are open to rate cuts”.

That said, the current state of the economy does not warrant a rate cut. While there is some softness from ISM and PMI readings, they remain above 50, or expansion mode. The latest Beige Book Report showed modest growth and “improvement” from the previous month:

Economic activity expanded at a modest pace overall from April through mid-May, a slight improvement over the previous period. Almost all Districts reported some growth, and a few saw moderate gains in activity.

In fact, Renaissance Macro found that the word count of “slow” or “weak” in the Beige Book has improved over last month.

While the headline Non-Farm Payroll print was disappointing, a number of internals indicating decelerating growth, but not a cratering economy. In particular, temporary jobs have historically led NFP, and so has the quits to layoffs ratio, which comes from the JOLTS report. Temporary employment continued to rise in May, albeit at a reduced pace, indicating deceleration but no contraction.

In the absence of negative shocks, these conditions do not scream for a rate cut. In the end, it may have been left to former New York Fed president Bill Dudley, who can speak more freely, to outline the Fed’s process in a Bloomberg opinion piece. Dudley laid out three scenarios:

I see three potential paths forward. First, both sides concede that a trade war is not winnable and eventually reach a deal of modest consequence. The U.S. unwinds tariffs, reversing the fiscal tightening, reducing the damaging uncertainty and restoring confidence in the economic outlook. If I were in the president’s shoes, this is the outcome I’d want because it offers the best chance of reelection.

Second, the sides stay in a holding pattern. Trade negotiations don’t resume, but nobody escalates. President Trump’s threat of a 25% tariff on the remainder of Chinese imports remains no more than a threat — as has happened with tariffs on European car imports. It’s still out there, but keeps getting pushed into the future. In this case, the economy and markets remain somewhat stressed. But over time, uncertainty subsides as people increasingly assume that this is how matters will remain.

Third, the trade war escalates further and the U.S. carries through on its threat of more tariffs. In this case, the impact on the U.S. economy becomes significant. Higher import prices boost inflation, and added fiscal tightening markedly increases the risk of a recession. Worse, China retaliates, with more negative consequences for the U.S. economy and stock market.

However, the Fed cannot act until it see the actual results [emphasis added]:

There’s not much the Federal Reserve can do before it knows which of the three scenarios will prevail. This reinforces its inclination to keep interest rates on hold. Officials would likely view the increase in prices as a one-time event, unless it somehow triggered more persistent wage inflation. That said, I suspect that Fed economists see the potential impact of uncertainty on activity as the more significant risk at this point. So if Trump goes further down the escalation path, it’s certainly possible that the Fed will cut its short-term interest-rate target by 0.5 percentage point over the next 12 months — as futures markets currently expect.

Beware of lurking negative shocks

The markets are adopted a risk-on tone this week. Negative sentiment became overly stretched. The alleviation of some trade related tail-risk sparked a rally. However, investors should be aware of lurking negative shocks from a number of different sources.

Hu Xijin, editor-in-chief of China’s official media Global Times, tweeted an ominous warning last week.

In addition, former American diplomat turned consultant Kurt Campbell revealed last week that China has begun a low-level harassment campaign against American companies.

“I work with Americans, largely American businesses, that are engaged deeply in China,” Kurt Campbell, chairman and CEO of The Asia Group, said in a speech at The Atlantic Council. “Without revealing details, I would say over the course of the last week, of 50 or so interlocutors in Asia, more than half have called and said ‘We suddenly have a problem’.”

Most of the difficulties have not yet been reported by the media. But companies have called to say that “suddenly their warehouse has been raided,” Campbell said. “Or maybe a movie company, the movie they wanted to be able to show, suddenly the airplane has not manifested for the movies, or the bank records need to be reviewed again.”

Campbell interpreted this campaign as a hint to the US:

“What we’re seeing now is phase two in the Chinese approach,” said Campbell, who served as the assistant secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs in the Obama administration.

“Now, it’s going to be a subtle message that if you proceed down this path, we’re going to retaliate against American firms,” Campbell said.

Trump scored a goal for the Chinese side when he visited the UK last week, and said publicly that while he would welcome a free-trade agreement with the UK, everything, including Britain’s National Health Service, was on the table. While I have not always been a fan of China’s mercantile trade practices, Trump’s deep intrusion into a trade partner’s longstanding institutions like Britain’s NHS will win him few friends among his allies.

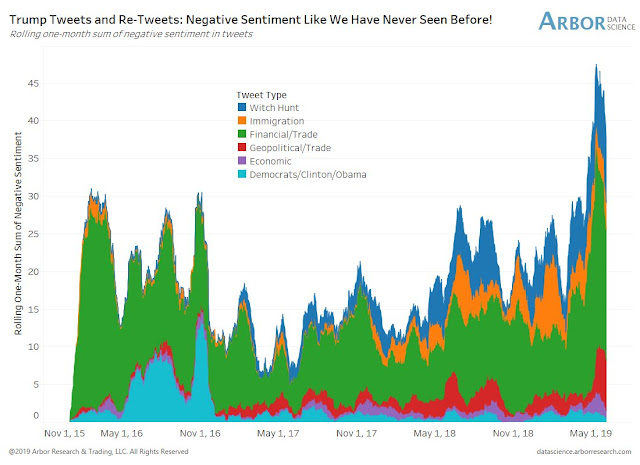

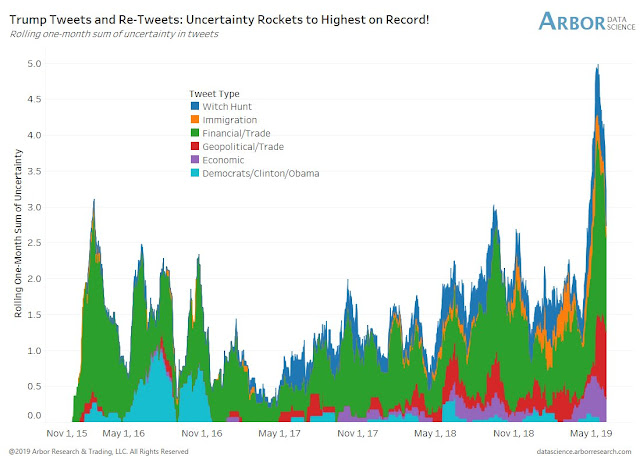

Then there is always the possibility of unexpected surprises from the Tweeter-in-Chief. Arbor Research compiled the history of Trump tweets and found that negative sentiment began to increase steadily about a year ago, and spiked to all-time highs in early May.

The Atlantic offered this framework for analyzing Trump’s policy surprises [emphasis added]:

According to current and former aides, who requested anonymity to speak freely, when Trump feels he has lost control of the narrative, he grasps at two issues: border security and trade. Those aides said he sees these topics as reset buttons, ways to rile both Democratic and Republican lawmakers and draw attention away from whatever dumpster fire is blazing in a given week. “Whenever a negative story comes around, his instinct is to pivot to immigration or trade,” a senior campaign adviser told me. “It’s kind of like his safety blanket. He knows that Fox and conservative media will immediately coalesce and change what the base is talking about.”

Specifically, the Mexican tariffs was just a reaction to the Mueller report:

That Trump reverted to tariffs on Thursday offers a clue as to just how distressing the past week has been for him. Trump is no stranger to bad weeks, of course. But according to the senior campaign adviser, he was particularly unnerved by the media attention Mueller’s statement received. “Mueller controlled the news cycle,” this person said. “It was 24/7 the last couple of days. And that’s what bothers him.” Added to that was the increasing number of 2020 candidates calling to begin impeachment proceedings against the president, a topic most have been loath to touch on the campaign trail. For any public bluster from the White House welcoming an impeachment fight, Trump has zero private desire to take one on, according to a second senior campaign official. “To be impeached?!? No one wants that,” the source told me in a text message.

One way to prepare for such surprises is to watch the sources of political irritants for Trump. Here are two stories that I am keeping an eye on.

The White House has directed former Trump aides Hope Hicks and Annie Donaldson not to provide the House Judiciary Committee with documents relating to the committee’s inquiry. The instances of resistance to congressional subpoenas by former and current Trump officials have been piling up. How will that battle play out?

In addition, Tucker Carlson at Fox recently gushed over Elizabeth Warren’s plan for economic patriotism and characterized Warren sounding as “Trump at his best” (link to video). Ouch! That’s got to hurt. Does this story have legs? How will Trump react?

Rate cut timing

After a long-winded analysis, we return to the original question. Will the Fed cut rates? I leave the last word to Fed watcher Tim Duy:

Fed officials have resisted sending signals about the direction rates, assigning equal possibilities of either an increase or a cut. The shifting balance of risks, however, make that an increasingly difficult story to sell. The escalation of trade wars from China to Mexico create substantial uncertainty for the outlook, and none of it good.

Some complain that the Fed would only be bailing out President Donald Trump in his ill-advised use of tariffs by cutting rates. Such charges will fall on deaf ears at the Fed. Policy makers may not like responding to Trump’s escapades with easier policy, but they ultimately have little choice but to do so. The Fed responds to shocks in a systematic fashion, even those created by the government. The Fed will respond to this shock with easier policy as they seek to sustain the expansion and meet their employment and inflation objectives.

Duy concluded that the likely timing of the first rate cut will be in September:

Although the stage is set for the Fed to cut rates, policy makers won’t have sufficient data to act until the end of the summer. A move at the September meeting is a reasonable baseline at this point. If the data deteriorate more quickly, or if markets seize up, pull that cut forward into July. If trade tensions ease and growth stays strong, push it back.

Will the on again, off again trade tensions drag on until Q3 or Q4? If so, expect a choppy range-bound and headline-driven market until the end of the summer and into the fall.

The week ahead

It is stunning how sentiment has taken a complete U-turn in one week. A week ago, my inbox and social media feed were filled with “the world ending” missives. By the end of this week, sentiment had changed to “we are going to fresh all-time highs” as a result of the relief rally.

The reflex rally was no surprise, as the market had become extremely oversold and sentiment had become excessively bearish. However, my base case scenario was the 2011 template, when the combination of the Greek Crisis and a possible budget impasse in Washington spooked the market. Prices chopped around in a trading range (shaded zone) until the ECB resolved the crisis with its LTRO program. The range-bound period was characterized by an initial fear spike, followed by a series of lower sentiment tops indicating fading fear.

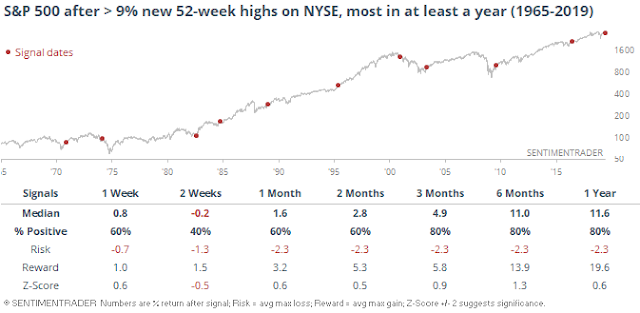

Fast forward to 2019. We are seeing some evidence of fading fear. What is different this time is the spike in S&P 500 new highs in the latest rally. New highs rose above 70 on Wednesday, which was a new 52-week high level indicating strong momentum. New highs continued to expand as the rally proceeded, and ended the week at 126. The same behavior was not evident during the choppy range-bound period in 2011, which suggests that the reflex rally may have further legs, and could continue higher in a V-shaped pattern, rather than the W that I originally envisaged.

SentimenTrader observed that the historical experience of fresh highs on NYSE new highs has generally been bullish.

To be sure, short-term sentiment had deteriorated to a crowded short, which accounts for the reflex relief rally. The AAII Bull – Bear spread was -20. In the last 10 years, the market had only one failure (red line) when the spread reached this level. In all other instances, the downside was limited and risk/reward was skewed upwards.

Troy Bombardia studied the historical record of what happened when the 4-week bull-bear spread fell below -14%, and he came to a similar conclusion.

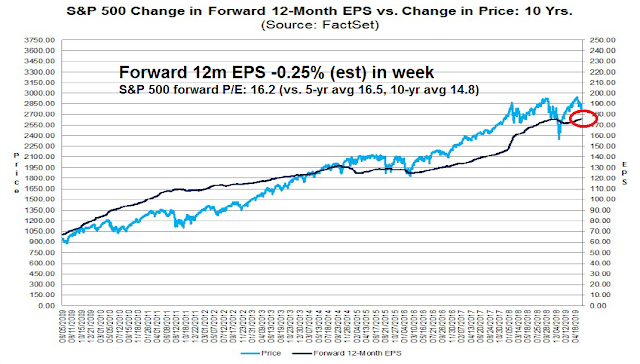

While the bulls may have temporarily seized control, the bears are still lurking in the woods, ready to pounce. FactSet reported that forward 12-month EPS estimates have started to fall, which may indicate that analysts are becoming increasingly jittery about the earnings outlook due to trade war risks. Keep an eye on this in the coming weeks to see this is a data blip.

The analysis of the relative performance of the top five sectors that comprise just under 70% of the index shows a mixed bag at best. Technology and Healthcare stocks have rebounded, but Financials and Communications Services are neutral, and Consumer Discretionary stocks are underperforming. It is difficult to see how the market can make significant headway until a majority of these top sectors show strong leadership qualities.

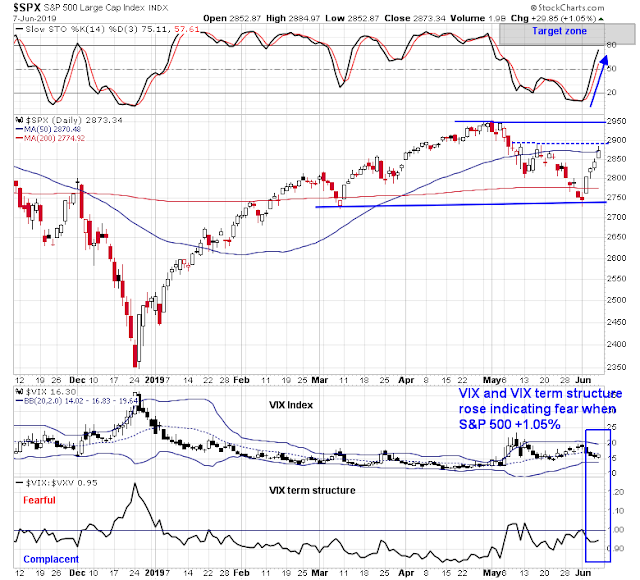

The daily S&P 500 chart also shows a mixed bag. The stochastic indicator recycled early last week and flashed a buy signal, but reading are close to overbought levels where the advance could stall. On the other hand, both the VIX Index and the VIX term structure showed increasing fear on Friday when the index advanced 1.05%, which anomalous and may be a sign that the market is climbing a wall of worry.

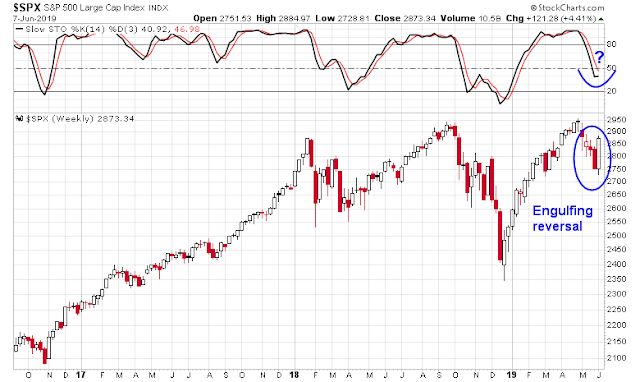

The weekly chart is flashing some potentially bullish signals. The stochastic indicator stabilized, indicating a loss of bearish momentum. Moreover, the S&P 500 exhibited an engulfing candle reversal, also known as an outside week, indicating that a possible price reversal is at hand.

Short-term breadth has become highly overbought and a pullback or consolidation could happen at any time.

Event risk will overhang the markets for the remainder of the month. We have the FOMC meeting in the third week of June, where the market has more or less priced in a Powell Put. In addition, Trump and Xi are expected to meet on the sidelines at the G20 meeting in the last week of June. These two events will represent high sources of uncertainty, and investors and traders are advised not to be sensitive to potential volatility.

I am inclined to think that the strong momentum exhibited by the market in last week’s relief rally is a bull trap. At a minimum, prudent risk management practices call for scaling trading positions to potential volatility. My base case remains a range-bound market, which calls for a trading strategy of fading strength and buying weakness.

My inner investor is neutrally positioned at the asset allocation specified by investment policy. My inner trader is bullish, but he lightened up some positions at the end of last week as the market rallied. He is preparing to sell the rips, and buy the dips.

Disclosure: Long SPXL