In the past week, a number of readers have expressed the conviction that US-China trade tensions are likely to ease in the near future at the upcoming Trump-Xi meeting, which will occur at the sidelines of the G20 meeting November 30-December Bloomberg reported that American farmers are so hopeful that they are storing significant amounts of their soy crop for future sale. What are the odds that will happen?

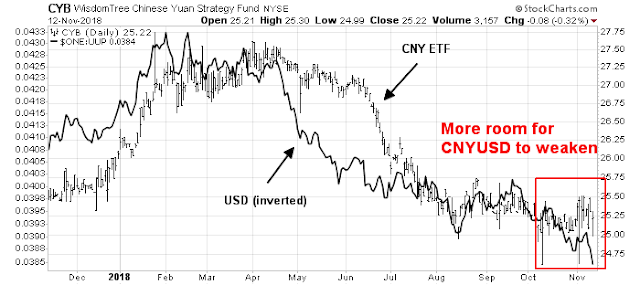

Certainly, there are some signs of a thaw. The strength of the USD Index indicates that there is more room for CNYUSD to decline further. But the PBOC dropped a pledge to allow the market to play a larger role in setting the exchange rate in its latest quarterly monetary report, which is a signal that the central bank is prepared to intervene to cushion yuan weakness.

While the steps taken by the PBOC is a useful start, here are the challenges facing an agreement on a trade deal.

Devaluation or capital flight?

One of the sources of friction during the trade war is the exchange rate level. Fretting over CNYUSD may not be useful in the current environment. A recent IMF paper, Macroeconomic Consequences of Tariffs, found that tariffs don’t work because the exchange rate devalues to adjust for the effects of tariffs.

We study the macroeconomic consequences of tariffs. We estimate impulse response functions from local projections using a panel of annual data that spans 151 countries over 1963‐2014. We find that tariff increases lead, in the medium term, to economically and statistically significant declines in domestic output and productivity. Tariff increases also result in more unemployment, higher inequality, and real exchange rate appreciation, but only small effects on the trade balance. The effects on output and productivity tend to be magnified when tariffs rise during expansions, for advanced economies, and when tariffs go up, not down. Our results are robust to a large number of perturbations to our methodology, and we complement our analysis with industry‐level data.

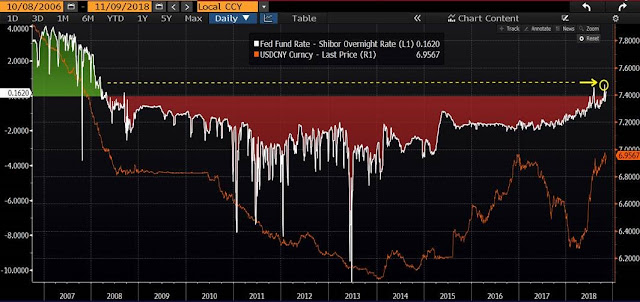

Everything else being equal, the Chinese yuan would naturally fall to adjust for the effects of the Trump tariffs. Indeed, there is a considerable interest rate divergence between the US and China, which puts downward pressure on the exchange rate.

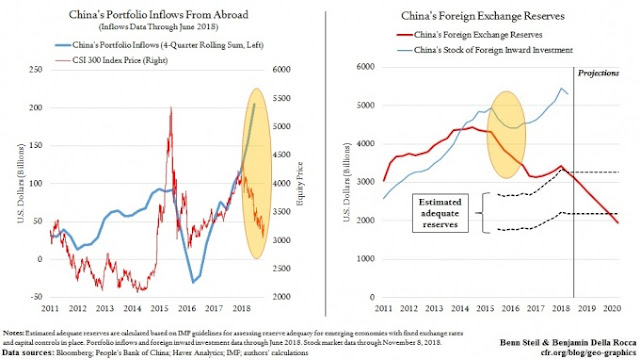

Benn Steil at the Center for Foreign Relations pointed out that the poor performance of Chinese equities puts additional downward pressure on CNYUSD.

Over the past two years, as our left-hand figure above shows, foreign portfolio investors have piled prodigiously into Chinese assets, helping to support the RMB. But history suggests this trend is about to reverse. While inflows have been rising, Chinese stocks have been tumbling—they are down over 20 percent from their January peak. Dreadful performance like this typically drives funds out of emerging markets. We may be seeing the beginning of such outflows in China.

Steil concluded with an ominous warning for Beijing should it decide to prop up its currency:

So in spite of President’s Trump’s repeated charges that China is manipulating its currency for competitive advantage in trade, all evidence suggests that it will continue to do the opposite. But if China were to sell reserves at the same pace as in 2015, its reserve levels would, by mid-2020, actually fall below the safety threshold implied by the IMF’s framework for reserve adequacy—as shown in the right-hand figure above.

The prospect of a balance-of-payments crisis, in which China would struggle to pay for imports and service foreign debt (a prospect considered outlandish a decade ago), highlights the urgency with which China must begin addressing the problem of high and rising corporate and local-government debt levels. The PBoC has no easy fix for these problems.

In the meantime, capital flows are continuing, albeit at a reduced rate, even before the deletion of the PBOC’s to allow the market to play a larger role in the exchange rate.

If the Chinese decide to prop up its exchange rate, it will have to choose between a market driven devaluation, or capital flows.

Preparing for the Trump-Xi summit

Ahead of the Trump-Xi meeting in Buenos Ares, here is what each side had to say. Bloomberg reported that Xi Jinping criticized “law of jungle” in veiled swipe at Trump at the inaugural China International Import Expo on Monday that “the practices of beggar-thy-neighbor” would lead to global stagnation.

Marc Chandler outlined the American position this way:

In a recent article in the Wall Street Journal, former Treasury Secretary Paulson seemed to express the views of many. If neither the US nor China changes its course, an “iron curtain may soon descend.” Pssst…the future has happened.

It can be debated when the Rubicon was crossed. Perhaps it was when Chinese officials had thought a deal had been struck with Treasury Secretary Mnuchin to buy more US goods to reduce its bilateral surplus with the US, only for President Trump to have torpedoed the agreement. That taught China that power does not lie with the US Treasury. Chinese officials also took that to mean that issue was not really the bilateral imbalance, but part of a larger attempt to stymie China’s rise. The Rubicon has been crossed.

Trump’s speech a couple of months ago should have left no doubt about what is happening: “When I came we were heading in a certain direction that was going to allow China to be bigger than us in a very short period of time. That is not going to happen anymore.”

Vice-President Pence was crystal clear in a recent speech. China was trying to shape the world in ways that are contrary to the US values and interests. Past administrations that sought to integrate China into the US-led order, like Paulson, in effect were co-conspirators to the violations of the rules to the detriment of America. Pence claimed that China was interfering with domestic policies. This is a strong claim.

Chandler took the gloves off in outlining the issues in this trade conflict:

Let’s be frank. Even before the Trump’s election, some Chinese officials thought that the US was trying to contain the PRC’s rise. It may or may not have been the case previously, but there can be little mistake now. The US is not just preparing for a fissure, it is fostering it.

NAFTA 2.0 is not much different than NAFTA 1.0 plus some of the measures agreed to in the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations and some domestic content changes. It also contained two other modifications, which mean very little for Canada and Mexico, but significant as a template for future agreements. The first is about intervention in the foreign exchange market and making it transparent and rare. The second is the gem. It essentially says that having trade agreements with non-market economies can end the bilateral deal with the US. “Non-market economies” is diplomatic-speak for China.

It can force countries who want privileged access to the US market to limit their trade with countries it judges unfit. Paulson fears that the US will be isolated because few will want to be locked out of the rapid growth that China continues to enjoy, even if not as fast as a few years ago. This seems to be an expression of defeatism among many of globalist camp.

Ahead of the summit, Xinhua reported that Xi Jinping met foreign policy guru Henry Kissinger. Xi stated after the meeting:

Adhering to the path of peaceful development, China remains committed to developing Sino-U.S. relations featuring non-conflict, non-confrontation, mutual respect, and win-win cooperation. We are willing to properly resolve the problems between the two countries through friendly consultations on the basis of equality and mutual benefit. At the same time, the U.S. side should also respect China’s right to choose its own way of development and China’s legitimate interests. [The United States should] walk along with China to jointly safeguard the healthy and stable development of Sino-U.S. relations.

Kissinger responded:

Under the current situation, U.S.-China cooperation is crucial to world peace and prosperity. I highly appreciate China’s efforts… The United States and China must better understand each other, strengthen strategic communication, continuously expand common interests, properly manage differences, and show the world that the common interests of the two countries are far greater than the differences.

Translation: Xi met Kissinger because of his reputation for strategic realism. Xi’s message to the old foreign policy warhorse is China is willing to sacrifice some of China’s interests, as long as it doesn’t harm Beijing’s long-term development strategy.

Is there enough daylight between the two sides for some kind of agreement? Marc Chandler doesn’t think so:

China initially appeared content to bide its time and Xi is positioned to outlast Trump. It tried offering concessions to ease the bilateral imbalance. These were ultimately rebuffed. The rhetoric on both sides has become more hostile. China has few friends in the US. Environmentalists, labor, human rights activists, businesses frustrated with the discrimination, and nationalists (President Trump’s self-identification) are vocally critical. Antipathy toward China is one of the few bipartisan issues in America, where the electorate and officials are exceptionally polarized. Democrats, who were often criticized by Republicans for being “soft on Communism” after the Kennedy-Johnson era, are not going to be similarly vulnerable in this new cold war.

This means that Chinese officials cannot in anyway count on the changes of the US electoral cycle to dial back the confrontation. While many in the US see a contradiction between China modernizing economy and an archaic political system, China experiences US government as unstable.

Consider that the US impeached one president who lied about a having slept with a consenting woman while electing another man president who appeared to have bragged about taking advantage of other women. Or consider that US political elite had sponsored a multilateral system of free mobility of goods and capital, but in one election in which the winner did not receive a majority of the popular vote, the strategy has been turned on its head. The vagaries of America’s electoral system and the gerrymandering that helps preserve it is not a stable foundation upon which China’s development strategy can reliably depend.

He concluded:

The situation is likely to get worse in the period ahead. It seems unlikely that China will make the concessions the US is looking for later this month when Trump and Xi meet. Trump then is likely to begin the formal process of putting tariffs on the remainder of Chinese goods. That process will take a couple of months and could be halted or modified before implementation, but in the meantime, it is consistent with the maximum pressure tactics the Art of the Deal requires. Moreover, on January 1, the 10% tariff on $200 bln of Chinese goods will be raised to 25%.

I agree. Both sides are dug in. It is difficult to see how either could back down given their respective positions. In particular, it will be difficult for Trump to conclude a NAFTA 2.0 style deal and “declare victory” without accusations of having caved to the Chinese.

Prepare for a minor risk-on rally on the hopes of a thaw ahead of the summit, and disappointment afterwards.

Chinese companies are starting to feel the credit crunch, by paying bond holders in kind rather than in cash;

https://www.barrons.com/articles/serving-up-a-new-flavor-of-payment-in-kind-bonds-1541847601

“First there were PIK bonds. Now we have PIG bonds.

PIK stands for payment in kind, which means that an investor gets paid in securities for interest or dividends, which is a handy contrivance for cash-strapped borrowers. Thanks to Bloomberg, we learn that Chuying Agro-Pastoral Group will use pork gift packages, instead of cash, to pay holders of 271 million yuan ($39 million) of its debt. “The Zhengzhou-based pork producer failed to repay 500 million yuan of local bonds due this week, amid a cash crunch caused by the spread of African swine fever,” according to the dispatch”.

As long as Peter Navarro is at the helm of China/US negotiations, the hard line is what’s happening. If he’s fired, things change, not before.