A decent interval has passed since China’s 19th Party Congress (see Beware the expiry of the 19th Party Congress put option), and it’s time to check in again on China to see how things are progressing. For the China bears, the overhang in debt looms large.

The worries are especially acute in light of International Monetary Fund’s publication of the results of its financial stability assessment of China. In connection with that review, the IMF issued the following warning about three sources of vulnerability:

- Excessive debt: In particular, concerns were raised over the rapid buildup of debt to keep non-viable zombie companies alive.

- Growth of shadow banking: The growth of the shadow banking system makes it more difficult to monitor and control the risks in the financial system.

- Moral hazard: The IMF also raised concerns over “moral hazard and excessive risk taking” because of the belief that the government will bail out troubled state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and local government financing vehicles (LGFV).

The concerns raised by the IMF echoes the writings of Winston Yung at McKinsey, who penned an article called “This is what keeps Chief Risk Officers in Chinese Banks awake at night“.

- Economic downturn leads to the emergence of credit risk

- Risk management cannot keep up with constantly changing business models:

- Asset liability mismatch

- Significant risk from off balance sheet activities

It’s all about real estate!

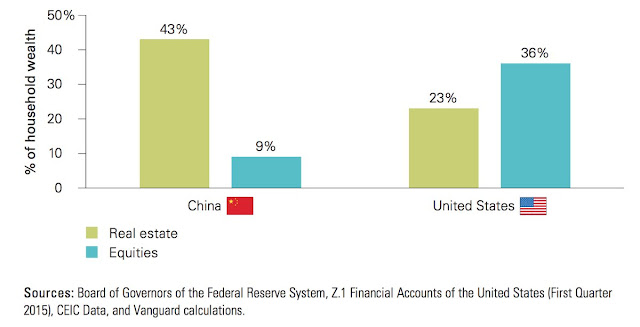

Simply put, the problems of credit growth have fueled a real estate boom in China. The following chart tells the story of a Chinese cultural affinity towards property investment. The latest figures show that 43% of household wealth was in real estate.

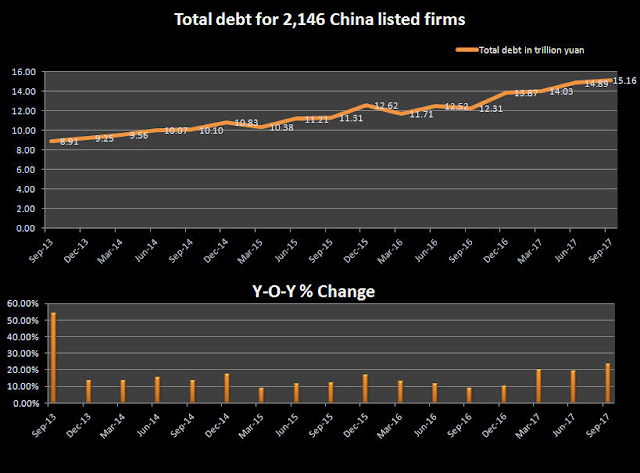

That’s just the household sector. Reuters analyzed the debt burden of the corporate sector and found that it had been growing steadily, despite government attempts at deleveraging.

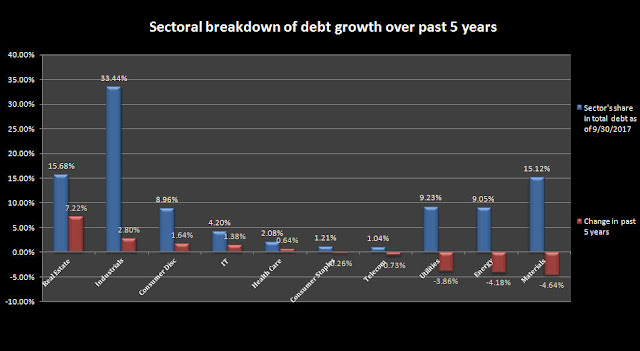

When broken down by sector, the biggest five-year debt growth rate came from (surprise!) real estate, though industrial companies have the largest proportion of debt outstanding. Despite these classifications, virtually all companies appear to be exposed to the real estate sector in some form, from either straight ownership, to property development, to financing.

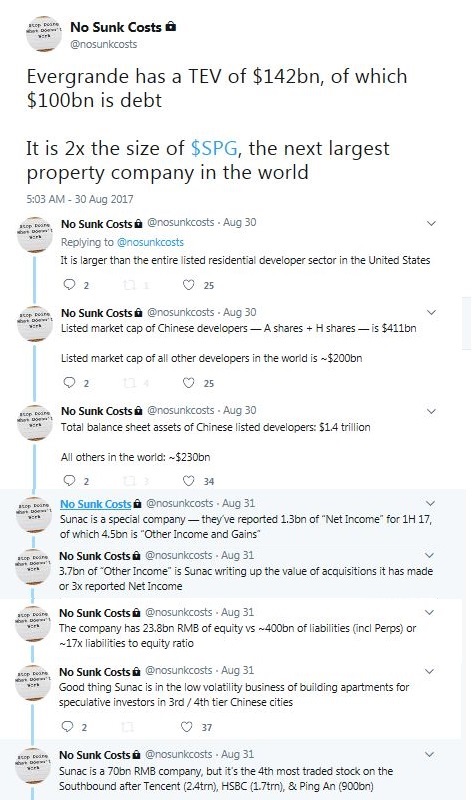

For another perspective, this series of (lightly edited) tweets from No Sunk Costs document the immense scale of the Chinese property sector.

Lenders gone wild

A recent Reuters article documents the shenanigans that have gone on in plain sight in property lending. When a property is sold, three bills of sale are prepared, with the open acquiescence of lenders:

When Zhu Chenxia bought a flat early last year from Lei Yarong in the up-market Nanshan district of China’s southern metropolis of Shenzhen, the two women drew up three purchase agreements to cover the deal.

Only one was genuine.

In the legitimate contract, Zhu agreed to pay Lei 6.49 million yuan (about $980,000) for the 96-square-meter apartment near the city’s border with Hong Kong, according to records filed in a Shenzhen court. With the help of her property agent, Zhu cooked up a second contract with Lei that overstated the value of the flat at 7 million yuan. This one was for the bank…

Mortgage fraud like the pair’s flouting of rules designed to protect banks is rampant in China’s roaring property market, according to interviews with buyers, sellers and dozens of property market insiders including real estate agents, lawyers, bankers, valuers and loan middlemen from three of China’s major cities and four smaller cities. Many of these people declined to be identified because they were familiar with or involved in “re-packaged” loan applications, the industry euphemism for these frauds…

Under the third contract she drew up with Lei, the Shenzhen flat was valued at only 2.8 million yuan, less than half its true value, the court records show. That contract was for showing to the taxman. At that value, Zhu would have saved more than 50,000 yuan in taxes, according to Shenzhen regulations.

Imagine the non-performing loan problem. For now, lenders are more interested in loan growth and therefore turn a blind eye to mortgage fraud, which appears to be quite common, and they appear to have adopted a “don’t ask, don’t tell” mortgage origination policy:

Reuters interviewed 12 property agents selling new and existing homes who said they had helped clients dodge lending rules. Another veteran salesperson in Shanghai who works at real estate company E-House China said around 50 percent of his clients engage in some kind of mortgage fraud. The person declined to be identified, and the company didn’t respond to questions.

Property agents often recommend buyers use so-called loan agents to help them secure funds from lenders. These loan agents have created an industry satisfying the demand for funds from borrowers unable to meet lending standards.

Bankers anxious to hit lending targets also introduce borrowers to these agents, according to property insiders. The use of loan agents allows the bankers to keep fraud at arm’s length.

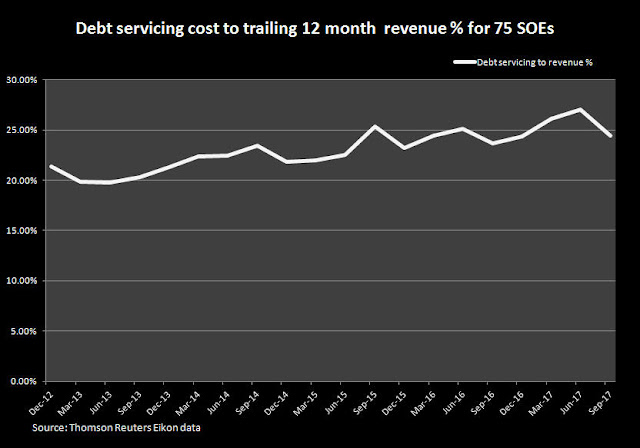

Besides household debt for property purchase, analysis from Reuters showed that SOEs are not immune from excessive debt burden. Debt burden at 75 of the CSI Central SOE 100 Index, which excludes financials, came in roughly 25% of revenue. That means operating margins have to be at least 25% for these companies to be profitable.

The government’s response

Just because a part of the economy is precariously positioned, in this case property and finance, doesn’t mean it will crash. In the wake of the 19th Party Congress, the authorities are taking steps to gently deflate the bubble, and pivot to a path of more sustainable growth. The good news is that Beijing has abandoned the “growth at any cost” model. The bad news is a shift toward an SOE driven growth strategy (via Tom Orlik at Bloomberg):

The early signs on economic policy from the 19th Party Congress are mixed. On one hand, Xi dropped the explicit mention of the commitment to double GDP from 2010 to 2020 — the basis of the annual 6.5 percent growth target. If that target is now sidelined, it will remove a significant distortion from China’s policy apparatus and a major cause of rising debt levels. On the other hand, China’s state planners appear to be in the ascendant. Industrial strategy loomed large in Xi’s speech. The call for a “stronger, better, bigger” state sector was echoed.

If that’s an indication of where policy makers’ priorities now lie, then it’s a troubling one. Deng’s clearest lesson for Xi is that market reforms — not state planners — are the path to China’s national renewal.

Last week, Caixin reported that the Politburo is taking additional steps to cool the property market:

The Politburo of the Communist Party of China, the country’s top decision-making body, said in a meeting on Friday that reforming the housing system and building a long-term policy for the real estate market are top priorities for 2018, according to the official Xinhua News Agency.

The bull and bear cases

Does this mean that Beijing tank the real estate market, which could then take down the Chinese economy? Let’s consider the bull and bear cases.

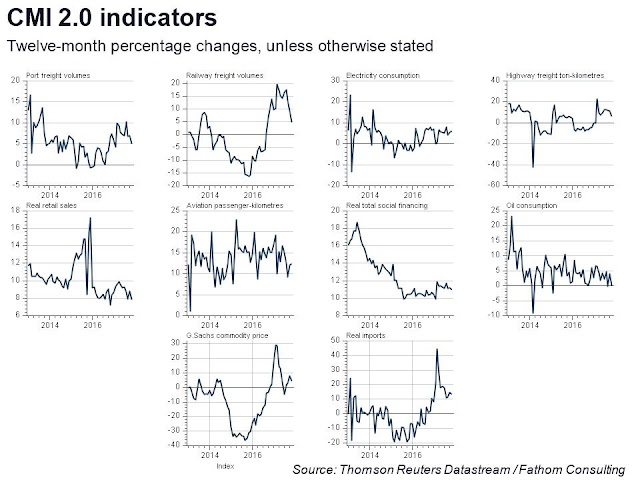

The bear case is relatively easy to make. China’s economy is sitting on a mountain of debt. The sugar high of the artificial stimulus leading up to the 19th Party Congress is starting to wear off. Fathom Consulting’s indicators of industrial activity are weakening.

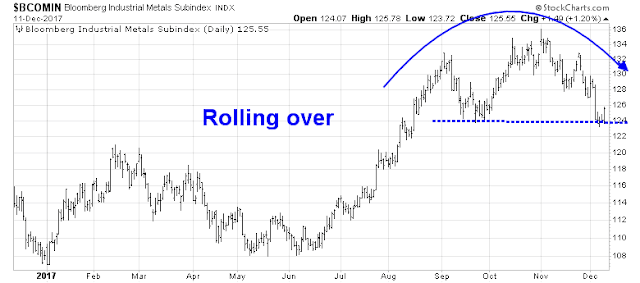

Real-time indicators, such as industrial metal prices, are rolling over.

Combined with Beijing’s stated intention to slow down the real estate market, the risk of a financial accident rises very quickly.

The bull case

I would remind readers that this site is not Zero Hedge. If you are looking for permanent bearishness, you should look elsewhere.

There is a case to be made that China is unlikely to crash. The PBOC still has plenty of bullets left if disaster were to strike. At a minimum, the PBOC has plenty of room to lower the RRR in order to inject liquidity into the financial system and the economy.

As an example, just as bond yields spiked in November, Tom Orlik pointed out that the PBOC injected significant levels of liquidity into the banking system. There were several consecutive days where the PBOC injected over USD 3 billion. To put those figures into some context, the Fed’s quantitative tightening program placed an initial limit of USD 6 billion of Treasury securities to roll off the Fed’s balance sheet per month – and the PBOC injected roughly half that amount into the banking system in a single day. This shows that, when push comes to shove, the PBOC is ready to act to ensure financial stability.

Chen Zhao, chief strategist at Alpine Macro, recently made the case that China is not at risk of a Minsky Moment in an FT article for the following reasons:

- Debt-to-GDP is an invalid metric for measuring risk: Debt is a stock concept. GDP is flow.

- China has plenty of room to service debt: The domestic savings rate is 48%.

- Credit risk is sovereign risk: Since the government and SOEs are so intimately involved in the economy, credit risk is sovereign risk. And most of the debt is denominated in RMB, which is a currency that the government controls.

The long Yuan trade

In addition, Kevin Muir at The Macro Tourist outlined an offbeat bull case for CNYUSD. His analysis began with an interview with hedge fund manager Felix Zulauf, who believed that Xi Jingping needs to slow the Chinese economy next year in order to have a strong rebound by 2021, when Xi is up for re-election:

China I believe is in an interesting position right now. You heard President Xi’s speech last week, and in 2021 there is the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist party and it’s very clear that they want to have a strong economy at that time. If you want to have a strong economy in 2021, you stimulate in 2020. And they are central planners. So that’s means they have to take their foot off the pedal in 2018, 2019. I think in ‘18 and ‘19, they will address the imbalances in the financial sector and that will slow down the Chinese economy in ‘18 and ‘19, which will also slow down the rest of the world.

So we are entering a period where sometime in ‘18, I would say the peak of the market will be in the first half, the peak in the economy is probably from mid-2018 on, and then we slow down into 2020.

And 2022 is the next Chinese Congress, and President Xi is probably the first leader who tries to run for a third time. So he wants to have a very good economy in 2021 and 2022. That means he has to first slow things down, restructure some of the imbalances in the system because if he tries to carry through, it could backfire on him. It could be the worst of all worlds. Namely a completely overheated situation, with high inflation rates, etc…

That’s why I think the leader of this cycle, China, is going to slow down next year.

Muir went on to explain that China is running an extremely loose fiscal policy through its “one belt-one road” initiative, but starting to run a tight monetary policy to cool the property market in 2018-19:

We have a Chinese President who wants to be re-elected shortly after his party’s 100th anniversary celebration in 2021. Therefore, it will be important that the Chinese economy is humming along at full speed at that time. To do that, he needs to stimulate in 2020, but the problem is, if he doesn’t tap the brakes now, he might risk overheating before then. President Xi will therefore take the hit, and get the pain over with in 2018 and 2019. Yet the story is further complicated by the fact that China’s long run infrastructure program is causing a hot fiscal policy. All of these factors add up to a much tighter PBOC for the next couple of years.

Call me an idiot, but I am tempted to take the long Yuan trade. I know that seems insane – all those really smart hedge fund managers are all forecasting a China collapse. But buying Yuan is probably better than betting on stocks going down because of the tight Chinese monetary policy. Not convinced it’s the best trade, and not even sure if I am going to do it in any real size, but I have often found the hardest trades, are often the best trades.

This scenario is based on the assumption that China can contain any fallout from a slowing real estate market.

Endogenous vs. exogenous shocks

I believe that resolving the bull and bear debate depends on whether the Chinese economy is subject to an endogenous shock driven by government policy, or an exogenous shock from abroad, which the central authorities cannot control. The bulls are largely correct in that most of the debt is denominated in RMB, and any so-called debt crisis will not be the typical EM crisis experienced in the past. Beijing can engineer soft landings, as long as they control both the regulatory and credit levers. If reform efforts threaten financial stability, the authorities can always back off. Indeed, we have seen the same start-stop pattern of deleveraging in the past few years.

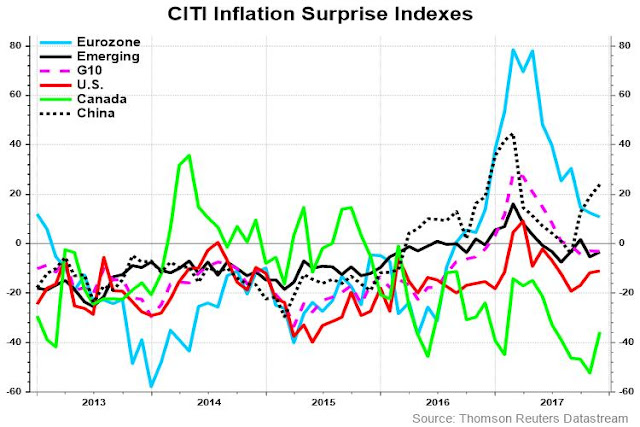

However, what happens if China is hit by an external shock? Global central banks are entering a tightening cycle. What would happen to China if American demand slows as the Fed normalizes monetary policy? Already, we are seeing signs of a global rebound in inflationary surprise, which will embolden monetary authorities to raise rates and discontinue their emergency QE rescue measures.

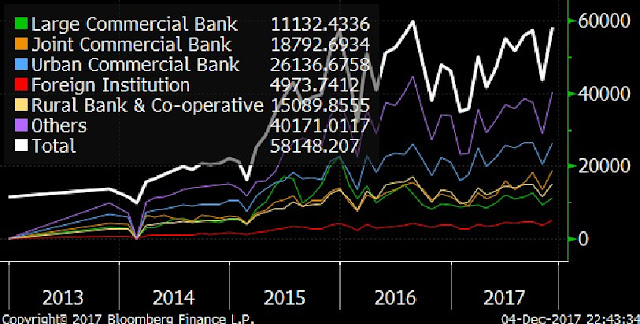

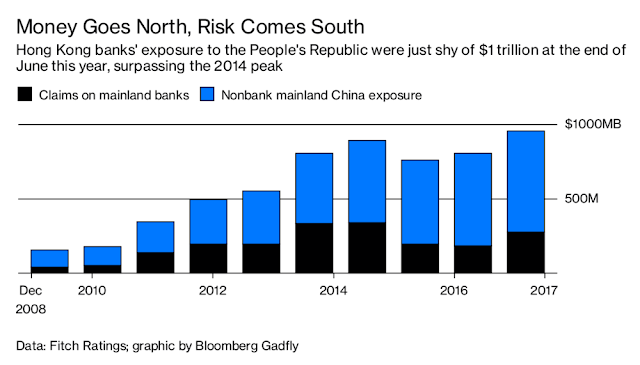

As the PBOE tightens monetary policy, this will drive Chinese corporations to seek cheaper financing offshore. Bloomberg found that borrowers are flocking to the Hong Kong branches of Chinese banks to borrow, and exposure is nearly USD 1 trillion. This level of exposure of loans in a non-RMB currency creates an additional level of risk for the Chinese financial system.

Imagine a scenario in which the PBOC tightens monetary policy, and CNYUSD appreciates as outlined in Kevin Muir’s thesis, then the US economy slows into a mild recession as the Fed tightens policy. Demand slows, Chinese corporate defaults rise, and starts to cascade. Under normal circumstances, Beijing could ease policy, but it may not be enough to offset falling demand through the trade channel. Even though China has a closed capital account, capital starts to flee and CNYUSD plummets.

Watch the Hong Kong market as the canary in the coalmine. Watch the CNY exchange rate. Watch Australian and Canadian real estate. Watch commodity prices.

Thanks for expanding on the Chinese political cycle. I think this is an important factor. Most investors are only watching the US economy.

Great supplemental material. Thanks!