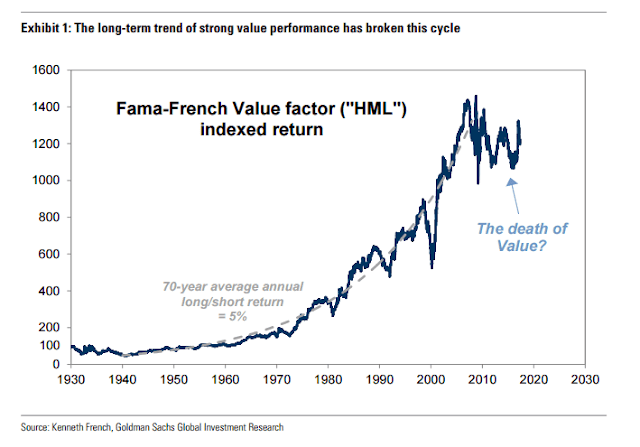

Recently, Ben Snider at Goldman Sachs published a report entitled “The Death of Value”, which suggested that the value style is likely to face further short-term headwinds. Specifically, Snider referred to the Fama-French value factor, which had seen an unbelievable run from 1940 to 2010 (charts via Value Walk).

Goldman Sachs went on to postulate that the value style is unlikely to perform well because of macro headwinds. This style has historically underperformed as economic growth decelerates. However, the investment implications are not quite as clear-cut as that, based on my analysis of how investors implement value investing.

Naive or pure value?

Consider how you might implement a value strategy. Imagine if you ranked all the stocks in your investment universe by the P/E ratio, which is a well-known value factor, and you created a buy list consisting of all the stocks in the bottom 20% by P/E. This buy list would have enormous sector bets. Since bank and utility stocks tend to have lower P/E ratios when compared to technology stocks, the buy list would be overweight banks and utilities, and underweight technology. That is what is known as a naive value factor.

Supposing that you didn’t want to a buy list that had sector and industry bets. You could rank your investment universe by P/E net of other factors, such as sector and industry, market cap (size), and so on. That’s what quants call a pure value factor.

This explanation is not meant to denigrate any single investment style. Some value investors, such as Warren Buffett, has successfully implemented naive value for many years by avoiding technology stocks as “too hard to understand”. Other quant investors have implemented pure value factor investing as a way of controlling risk.

The Fama-French value factor is a form of a pure value factor. By contrast, the Russell 1000 Value Index (RLV) and Russell 1000 Growth Index (RLG) have significant sector weight differences and can be better characterized as naive value bets.

That’s where the difference in value investing lies.

Sizing up the macro bets

One way of sizing up the value bet is to consider the sector weightings between RLV and RLG. As the chart below shows, a long naive value (RLV)/short growth (RLG) portfolio would be long Financial Services and Energy, while underweight Technology and Consumer Cyclical, though much of the latter is an AMZN effect because of the large weight that stock has in the Consumer Cyclical sector.

While Tech stocks have been on a tear for most of 2017, I would caution that differences in sector weights do not fully explain the value style shortfall. Analysis from GMO stated:

It should be noted that value’s underperformance cannot be explained solely by its relative underweight of the Information Technology sector. For example, in the US, a sector-neutral value portfolio consisting of the cheapest quartile of stocks from within each sector would still have underperformed a sector-neutral growth portfolio by approximately 4% in the first 5 months of 2017.

Nevertheless, let us consider the macro implications of these value and growth sector bets using the yield curve. The shape of the yield curve has been long been used by fixed income investors to measure the market’s growth expectations. A steepening yield curve is taken as a sign that the market expects rising economic growth, while a flattening yield curve is a sign of growth deceleration.

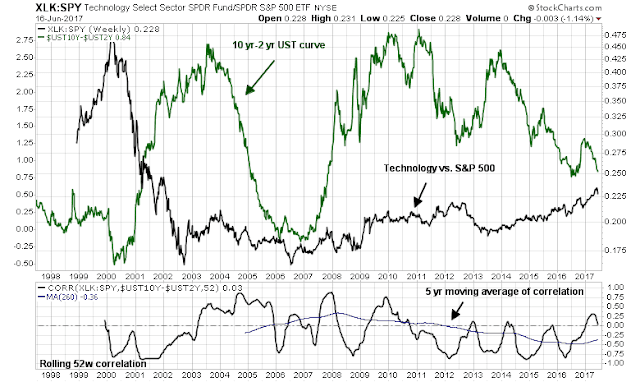

The chart below shows the relative performance of Technology stocks against the market (black line, top panel), and the 52-week rolling correlation of the market relative performance against the yield curve (bottom panel), along with a 5-year moving average of the rolling correlation. As the chart shows, the relative performance has had a slight negative correlation to the yield curve. In other words, In the last five years, Tech stocks have tended to outperform when the yield curve is flattening, which indicates a growth deceleration.

By contrast, here is the same chart for Financial stocks, which has shown a positive correlation with the shape of the yield curve. These stocks tend to perform better when the yield curve steepens.

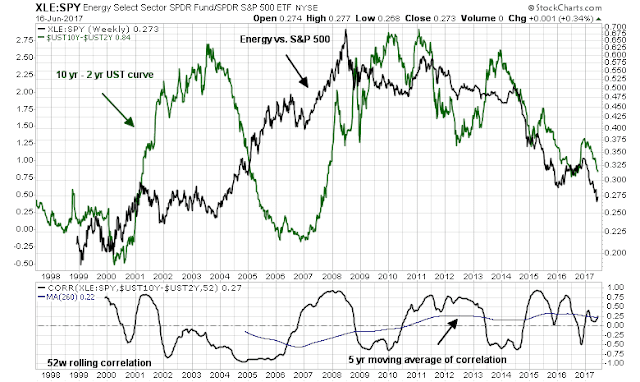

A similar analysis of the Energy sector came to the same conclusion. In the last decade, Energy stocks have outperform when the yield curve steepens, indicating accelerating growth.

In conclusion, the Goldman Sachs macro analysis of how value performs under differing economic growth conditions only tells part of the story. It’s not the current state of the economic growth conditions that matter, the direction of change of growth, whether it’s accelerating or decelerating, matters just as much.

A contrarian setup

The foregoing analysis has led me to believe that Goldman’s publication of “The Death of Value” report is setting up for a revival of the value factor. Consider how such a pain trade might unfold. The latest BAML Fund Manager Survey shows that US institutions are overweight the big growth sectors (Tech and Discretionary) and slightly underweight the big value sectors (Banks and Energy).

In my last post (see The risks are rising, but THE TOP is still ahead), I suggested that the stock market is poised for a revival of the global reflation trade after a brief June swoon, or hiatus. The recovery would be characterized by the leadership in capital goods stocks, which may be just staring now, and capped off by a surge in inflation hedge sectors such as gold, energy, and mining. The resurgence of the reflation investment theme would also be accompanied by a steepening yield curve.

Should the market’s perception shift to a better growth outlook, then the yield curve will begin to steepen again, which would benefit the big value sectors of Banks and Energy while hurting Technology.

As well, current positioning suggests that a long value (Energy and Banks) and short growth (Technology and Discretionary) is a promising contrarian setup. That trade may be still a little bit early. I would prefer to wait for definitive signs that Energy and Mining stocks have shown signs of a relative market bottom before committing to that trade.

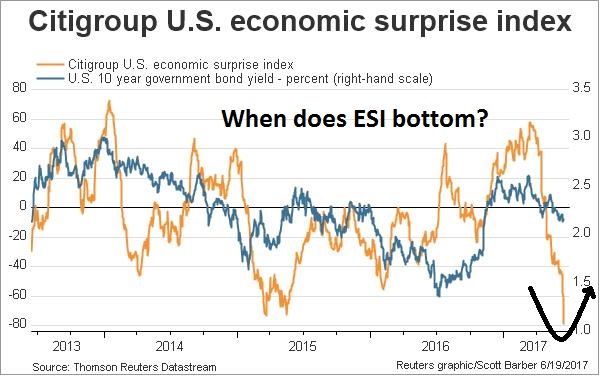

An alternative signal to buy value stocks might be a bottom in the Citigroup US Economic Surprise Index (ESI). This index is designed to measure whether macro releases are beating or missing expectations, and it is also designed to be mean reverting. As the chart shows, ESI has been correlated with Treasury yields. When ESI does turn up, yields will also rise, which will probably coincide with a steepening yield curve.

That will also be a signal of a more friendly environment for Russell 1000 Value stocks.

In my opinion, a key reason value stocks are underperforming is due to the disruption caused by the digital revolution. As companies and industries suffer great change their stocks seem cheap compared to historical norms. Before the current technology era, value stocks would get cheap in recession and return to the mean in profitability in the next strong business cycle. Business conditions didn’t change much cycle to cycle. Now technology wipes out large segments, retail for instance where Amazon.com is disrupting or a whole industry like oil where technology has tipped the supply/demand.

Value might get very temporarily too cheap versus growth and momentum factors (the two winners in disruption) and can be traded briefly but I would expect these technology disruptions to continue to weigh on companies longer term that aren’t adapting fast enough. Value will disappoint. Momentum will be surprisingly resilient.

Cam,

The case being made here is for steepening of the yield curve that could see value outperform growth.

As the Fed increases fed funds rates, isn’t there a case to be made for the yield curve to flatten instead of steepen? The 2-10 year curve is also showing a similar trajectory. Somewhat puzzled.

Yes, you are correct. Fed action to tighten monetary policy “should” flatten the yield curve.

I am postulating a steepening based on a growth expectation revival because the ESI is so low and should rebound soon. If that were to happen then growth expectations and stock prices would get a second wind. So would value stocks because of their sector exposures.

Hope ESI turns around, and soon.

Love the intelligent diversity of opinions!

This debate about ‘Value Investing’ is so key. In my opinion, it’s the reason experienced investors and portfolio managers are doing so poorly. I’m doing new research on the Momentum Factor so what I say in this post is from that. Sorry for the length of this post but you hit a nerve with today’s blog.

You’ll note in the bottom left of the first chart on Value Investing that is says the “average long/short return”. This is how they test factors such as Value, Momentum and Size. Researchers construct two indexes, one with high characteristic and the other with low. They combine the two in one long/short index by going long the high and short the low. In the case of Value, they take PE ratios and price to book type things to establish Value. So the index will be long companies with low PEs and low price to book and short high PE and high price to book. The average difference in performance was 5% a year for 70 years. That’s a huge win for the value investing approach.

Value analysis flourished until 2008. This is the era of Warren Buffett and the huge numbers of CFA grads. Companies needed large asset bases to operate and make a profit. Retailers needed stores. Manufacturers needed plants and equipment. The cost of these were a barrier to entry of competition. Basic business methods in various industries didn’t change from cycle to cycle, decade after decade. Retailers always needed stores. Steel companies needed foundries and inputs from mines. For Value-style to outperform by 5% a year, it meant that investors erred by that much on average in analyzing how important large asset bases and cheap stock prices to earnings, were. It showed that when stock prices fell and PE ratios fell, they would revert back to means and reward the bargain hunters.

Flash forward to today’s world of the digital revolution and globalization. Ideas are key drivers of success in business and the biggest asset of successful companies are the people. These are not assets on the balance sheets. Apple sells a huge amount of physical products but does not manufacture them. Airbnb helps people sleep in rented rooms without owning hotels. So price-to-book and relative PE calculations will have the Value Index long Walmart and short Amazon.com.

Of course, there has always been high growth companies with high PEs and high price-to-book ratios in the stock market. They have had their bursts of outperformance. The Nifty Fifties era of the early 1970s and the Dot.com era at the turn of the century are examples. But these were a small portion of the business landscape, over-hyped and overvalued.

I put forward the notion that “This time it’s different.” The Dot.com bubble led to rolling out fiber around the world for the internet to flourish and then the smartphone was introduced in 2007, just a decade ago. In my mind the Value Index chart’s breakdown in relative performance started then on a more permanent basis. Before 2007, if a company was successful with strong growing earnings and high price-to-book that meant it was cheap for competitors to set up and attack their business. That’s not the case anymore. Google’s map or Youtube apps are not large physical assets on the accounting books but it’s virtually impossible for competitors to replicate. Apple’s design teams are another case in point.

Previously successful, established companies with large asset bases are being disrupted by nimble knowledge-based competitors with few physical assets. If you are buying Value rather than Growth or Momentum, just realize that you are in effect saying large physical assets on their books are a better thing to own than new digital knowledge.

That begs the question. Are the high flying stocks of these new digital knowledge companies just another of mankind’s many investment bubbles that will burst?

Many years ago, I read a quote that said, “When a great stock broker hears that heroin addiction is up 20%, he asks who makes the needles.” Well, recent research is showing that smartphones are highly addictive. I saw a Charley Rose interview of a former high ranking Google exec talk about how powerful this is and his concerns that companies like Facebook and Google are constantly changing to make them even more addictive with AI fine tuning. He left Google when he flashed the alarm and management didn’t listen. If, rather than a cellphone, I was to tell you that I had a stock you could invest in that just invented the perfect drug that was highly addictive, socially accepted and growing so fast that it is heading towards all of humanity becoming addicted users, you would invest in that stock. Cigarette companies keep flourishing with their harmful addictive product even as the number of users falls.

Once a person becomes addicted to the smartphone, they are exposed to huge amount of advertising and data. That is causing vast changes in so many things. All I can say is that we are very likely, no actually certainly, underestimating the impact. We, older more experienced investors are trapped in our sense that this is just a phone. When in fact, it’s an addictive device that is transforming its users view of their world. Just look around the airport when you’re wait for your plane. Those folks aren’t talking to people, they are staring at a hand-held, high speed computer screen linked to vast amounts of easy to access addictive data. Every day, it’s getting easier and cheaper to access and more personally designed to press each users individual addictive buttons by AI geniuses.

For sure, there is a huge financing of AI because it’s so valuable to fine tune the smartphone user’s experience. That is the focus of discovery but this AI knowledge will then also burst into so many other areas outside smartphones as it improves and looks for more markets. This will have a huge impact on jobs, society in general, politics and business.

I believe all of this makes the future investment environment very unknowable. Experienced, previously successful portfolio managers are doing poorly because their accumulated knowledge is no longer an asset to performance, it’s a liability in this evolving new business environment. It’s futile, in my mind, to simply using old measures like PE ratios and price-to-book in a value investing approach when unknowable disruptive forces can impact a company’s fortunes profoundly in the future.

This is why I use a personally improved, Momentum-style of investing for my client portfolios and it’s working like a charm. I was recently voted a top ten portfolio manager of the year in Canada for 2016. This strategy keeps one’s portfolio on the winning side of all of this and there will be huge winners. All one has to do to shift to Momentum-style is admit to oneself that this new digital environment is huge and unknowable as to how it will unfold. One can then humbly set ego aside and stop predicting using your pool of personal experience that prevents you from understanding the futility of trying to join all the dots in this maze of new forces. Don’t get me wrong. This is a difficult thing to swallow. It was for me.

Short term trading when using momentum simply forces you to stay within outperforming sectors and stocks in them. Stocks and industries that are down and seem bargains are often a value trap for some complex, digital revolution reason that you will discover later after you lose money.

Here’s a link to my book on improved momentum entitled ‘The Pathway … Your money in a time of change.

http://www.thepathway.ca/

All the best. We are in this together.

Ken

Thanks for sharing the characteristics of value vs. growth in today’s context. Makes sense. Did not realize how things today are vastly different than the Buffet times.

Amazon is now moving into bricks and mortar arena with its purchase of Whole Foods. This is likely to increase its cost of doing business (per Ken’s comments above). Amazon may be able to justify this move based on technological leverage. However, competition can also implement similar technological innovations. Technology is non monopolistic and causes its own deflation. We shall see how the WFM acquisition affects Amazon’s bottom line.