Recently, there has been a parade of regional Fed presidents calling for a serious consideration of a rate hike:

- Boston Fed’s Rosengren, who appears to have becoming more hawkish after being a dove

- Richmond Fed`s Lacker

- San Francisco Fed`s Williams

- Kansas City Fed’s George

- Atlanta Fed’s Lockhart

The hawkishness of regional presidents is no surprise. Bloomberg reported that the boards of eight of 12 regional Feds had pushed for a rate hike.

The hawkish tone by regional Feds has been offset by more the dovish views of Fed governors. Fed governor Daniel Tarullo told CNBC last week that he was open to rate hikes in 2016, but he wanted “to see more inflation”. Today. uber-dove Fed governor Brainard stayed with a dovish tone in her speech stating that the “asymmetry in risk management in today’s new normal counsels prudence in the removal of policy accommodation”.

The market’s intense focus of when the Fed moves rates is the wrong question to ask. Rather than ponder the timing of the next rate hike, the better questions to ask is, “What is the trajectory of rate normalization for 2016 and 2017 and what are the investment implications?”

The Hamilton checklist

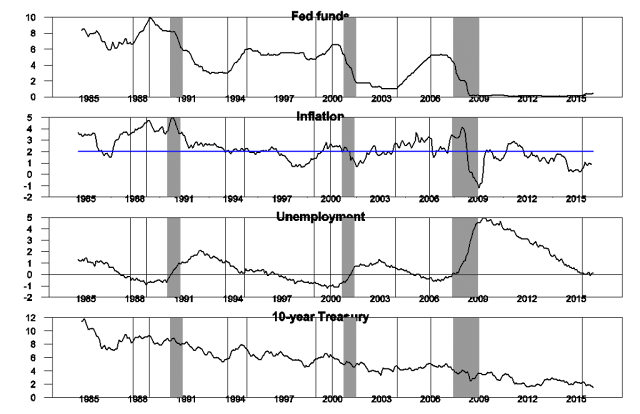

James Hamilton studied the past four rate hike cycles and he found common elements that undoubtedly had profound influences on Fed policy:

These 4 episodes have several things in common. First the inflation rate rose during each of these episodes and was on average above the Fed’s 2% target, a key reason the Fed moved as it did. Second, the unemployment rate declined during each of these episodes and ended below the Congressional Budget Office estimate of the natural rate of unemployment, again consistent with an economy that was starting to overheat. Third, the nominal interest rate on a 10-year Treasury security rose during each of these episodes, consistent with an expanding economy and rising aggregate demand.

If we are to focus on the likely trajectory of interest rates for this year and next year, let’s consider the Hamilton checklist:

Inflation rate above the Fed’s 2% target: You have to be kidding! One of the mysteries of this expansion has been the tame behavior of the inflation rate. While Core CPI has been rising, neither core PCE, which is the Fed’s preferred inflation metric, nor inflationary expectations has moved above the Fed’s 2% target. In fact, inflationary expectations has been falling, not rising.

Unemployment below the natural rate: No. The current unemployment rate stands at 4.9%, while the current CBO estimate of the natural rate of unemployment is 4.8%.

Tim Duy recently worried about the risk of a policy error if the Fed ignores the warnings from a maturing economic expansion and tightens the economy into recession:

I don’t know that there is an economic mechanism at work here. I don’t know that there is a law of economics where the unemployment can never be nudged up a few fractions of a percentage point. But I do think there is a policy mechanism at play. During the mature and late phase of the business cycle, the Fed tends to overemphasize the importance of lagging data such as inflation and wages and discount the lags in their own policy process. Essentially, the Fed ignores the warning signs of recession, ultimately over tightening time and time again.

For instance, an inverted yield curve traditionally indicates substantially tight monetary conditions. Yet even after the yield curve inverted at the end of January 2000, the Fed continued tightening through May of that year, adding an additional 100bp to the fed funds rate. The yield curve began to invert in January of 2006; the Fed added another 100bp of tightening in the first half of that year.

This isn’t an economic mechanism at work. This is a policy error at work.

Rising 10-year Treasury yields (in response to better growth outlook); A qualified yes. The 10-year Treasury yield has edged up from its recent lows, but not very much.

James Hamilton concluded that it’s too early for the Fed to think about starting a rate hike cycle:

But in several other respects this isn’t shaping up like the earlier cycles. Inflation is a little higher than it was last year, but is still a full percentage point below the level that the Fed says it would like to see. The unemployment rate has barely budged, and has not yet moved below the CBO estimate of the natural rate. And most revealing of all, the long-term interest rate has fallen dramatically, completely unlike the behavior in a typical Fed tightening cycle.

In order to calm the cacophony from the hawks and keep peace within the FOMC, Yellen will probably respond with one rate hike in December, not September. The bigger question is how much and how quickly they raise rates next year.

Investment implications

I have warned about a possible stock market top in 2017 from to a Fed induced recession (see Stay bullish for the rest of 2016). For now, inflation and inflationary expectations remain dormant. The Brookings Institute pointed out that the US is currently in a tightening phase in its fiscal cycle, but that may change with a new president as the rhetoric from both Clinton and Trump tilt towards expansionary fiscal policies. Should a new administration propose more government spending, the Fed may feel greater leeway to respond with a resumption of its rate normalization policy.

In my post (see Stay bullish for the rest of 2016), I had postulated that a series of Fed rate hikes could push China into a slowdown and possible debt crisis. Such an event has the potential to have a domino effect on the rest of the world. My hypothesis gained support from this Bloomberg report of Deutsche Bank’s model of the global effects of a Fed rate hike, which shows that China gets hit the most of any country.

As a reminder, the analysis from Deutsche only models the effects of a single quarter-point rate hike. If the Fed were to start a tightening cycle, it would raise rates much more than that. However, I would caution against multiplying the estimated rate hike effects by the number of quarter points that you expect as the effects of these models tend to be non-linear.

In conclusion, the timing of the next recession is highly dependent on the Fed’s reaction function and perception of incoming data. I am not in the business of making investment decisions by anticipating model readings, but by reacting to them. It’s far too early to get bearish and I am enjoying the party thrown by the bulls, but I am starting to edge towards the door. The cops are going to come and raid the party at some point, I just want to be ready.

As usual Cam has written a well reasoned and exhaustive explanation on interest rates. The only missing ingredient I contend is market forces. Since July for some inexplicable reason the Libor rate has been rising even though the Federal Reserve, the ECB and the Bank of Japan have been making dovish statements.. Market forces are stronger than the Central Banks. Remember the time Soros took on the Bank of England in the currency market. The Federal Reserve can control the short end of the yield curve. The long end is influenced by uncontrollable market forces which for reason wants yields to rise.

The recent increase in LIBOR seems to be due to regulatory changes, and its not a recession signal. http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21705854-new-money-market-regulations-are-pushing-up-benchmark-interest-rate-secular-shift?frsc=dg%7Ca

The rate hike cycle this time may be somewhat different. From today’s vantage point, it appears that the Fed funds rate may not be able to go much higher by comparison to previous cycles.

2. Full employment may be lower than traditionally thought (see above graph). There are secular trends that will likely put upwards pressure on unemployment (Artificial Intelligence as an example; driverless cars, smaller housing in the US, trend towards temp employment, boomer retirement etc.).

3. All parties eventually come to an end, and then there is a bad hangover. The world is awash in fiat money and whiff of deflation. This too shall end (badly).

4. The fiscal impact cycle above shows elegantly how fiscal policy affects GDP growth. What is not implicit in the graph is the accumulated debt in the last two expansions. This time may be different. We may not be able to afford another expansion, though one never knows with politicians.