I am seeing an unusual level of rising anxiety over the political implications of Brexit. Last week, Stratfor published a report entitled “Brexit: The First of Many Referendum Threats to the EU”, which detailed the threats of additional referendums to the future of Europe.

Jim Rogers, writing in the Daily Reckoning, also painted a dire picture of the world after Brexit:

Are we at a point right now where it feels like it’s accelerating. People all over are very unhappy about what’s going on. If you read history, there are a lot of similarities between now and the 1920s and ’30s. That’s when fascism and communism broke out in much of the world. And a lot of the same issues are popping up again.

Brexit could be a triggering moment. This is another step in an ongoing deterioration of events. It’s also an important turning point because it now means the central banks are going to print even more money. That may prop the markets up in the short term…

The European Union as we know it is not going to survive. Not as we know it. Britain voted to leave, and France could very well be next. Why France? One of the main reasons is because the French economy is softer than the German economy. At least in Germany people are still earning money and making a living, despite all the recent turmoil. In France, the same malaise that’s settling over the U.S. and other places is settling in. And it’s going to spread.

There is no place to hide with what’s coming. I’m not saying it’s coming this year, or even the next. I can’t give a specific date. But imbalances are building up to such a degree, they just can’t continue much longer.

In addition, Philippe Legrain fretted about Brexit opening the door to European disintegration in an essay in Project Syndicate.

I beg to differ. In fact, the Brexit experience has made Europe stronger, not weaker.

Brexiteer fantasies

I recognize that the desire for Brexit is mainly emotional and not economic. Bloomberg reports that a survey by the U.K.-based Centre for Macroeconomics shows that the main reasons that voters favored Brexit were not economic. Simply put, Project Fear did not work to scare voters to believe that the UK would be far worse off under Brexit than inside the EU.

In the wake of the vote, we get silliness from the hard core Brexiteers such as this petition to remove French words from British passports.

The sentiment is reminiscent of a Monty Pythonesque caricature of the English-French relations here:

…when a simple search in Google shows that even the word “passport” has French roots.

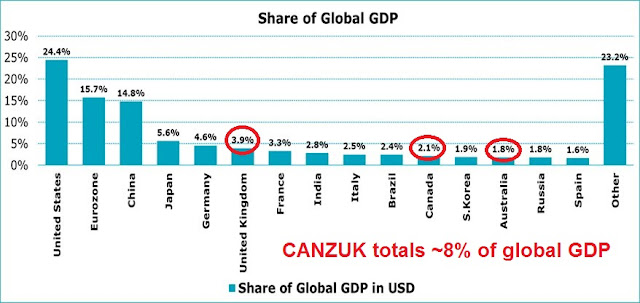

Then I came upon this fantasy of trying to re-create parts of British Commonwealth with CANZUK:

If that is why the British are leaving, the natural question is: are there any countries out there with similar values and similar income levels with whom the British have greater cultural and constitutional similarity? That is obviously a question that answers itself: Canada, Australia and New Zealand are closer to Britain, constitutionally and culturally, than anywhere in Europe. And their income levels are fairly similar: in 2014, the U.K. had a GDP per capita of about US$46,000, versus US$44,000 for New Zealand, US$50,000 for Canada and Australia a little higher at US$62,000.

Sorry, the British Empire is long gone and the Commonwealth is as effective today as la francophonie. The old supply chains, which are the key elements of Commonwealth-based trade links, have atrophied and disappeared. The world has moved on since the 1950s and 1960s. Canada’s main trade focus is on North America. Australia and New Zealand’s main customers are in Asia.

CANZUK countries occupy very different parts of the world and trade volumes between each other is relatively low by global standards. The synergies from a free-trade pact would therefore be relatively low. In addition, the share of global GDP of these countries only amount to 8% (h/t Jereon Blokland for chart).

Why even bother?

The reality: Devil is in the details

For readers who are unfamiliar with the Brexit process, here is a useful FAQ and guide from the BBC. Needless to say, there is much that needs to be done and many details that have to be ironed out. The latest government actions show that the UK is utterly unprepared for the tasks ahead. Here are just some of the obstacles it faces:

- Pending litigation challenging the Brexit process;

- The threat of Scottish succession;

- As the government faces a bewildering array of demands from the 27 other European states…

- The negotiation team isn’t even in place. HM Treasury is advertising to fill the post of Director General, Financial Services. This is a trade negotiator whose task is “defining and negotiating our new relationship with the EU in the field of financial services”.

Trade negotiations are, by their nature, detailed and intricate. Agreements can’t be slapped together overnight. Here is a real-life example to consider.

Recently, the province of British Columbia slapped on a 15% tax on real estate for any non-resident buyer as a way to alleviate the price pressure in Vancouver (see CBC story). A Toronto lawyer responded with an Op-Ed entitled “B.C. just violated NAFTA with its foreign property tax — and we could all pay for it“. He contended that NAFTA requires Canada to treat the citizens of the other signatories, namely the United States and Mexico, the same way as it treats Canadians. Slapping a tax on foreign purchasers of Canadian real estate amounted to a treaty violation. Canada also has trade agreements with numerous other countries with similar provisions as well and the tax would also violate those treaties.

There was much buzz on social media on this topic, until an alert reader pointed out that Canadian trade negotiators had already addressed that particular issue.

With any agreement, the devil is in the details. Unless you think these things through very carefully, you don’t know what could trip you up in the future.

Pour encourager les autres

It is therefore no surprise that as Europeans woke up and realized the implications of Brexit, Euroskeptic support fell dramatically (via Reuters):

In an IFOP poll taken between June 28 and July 6, a few days after Britain’s vote to leave the EU, support for EU membership jumped to 81 percent in Germany, a 19 point increase from the last time the question was asked in November 2014.

In France, support surged by 10 points to 67 percent. In both countries, that was the highest level of support since at least December 2010, when IFOP started asking the question.

“Brexit shocked people in the EU,” Francois Kraus, head of the political and current affairs service at IFOP, told Reuters on Wednesday.

“Seeing the Eurosceptics’ dream come true must have triggered a reaction in people who usually criticise the EU and blame it for decisions such as austerity measures.

“But when people realise the real implications of an exit, there’s new-found support for the European project,” he said.

In the euro zone’s third-largest economy, Italy, support also rose 4 points, to 59 percent, the highest since June 2012. In Spain, some 81 percent of those polled said EU membership was a good thing, a 9 point increase in 2-1/2 years.

People in other major European countries were not keen to follow Britain’s example and hold referendums on EU membership: a majority of people in Germany, France, Italy, Spain and Poland, said they were against such votes.

Should a referendum be held, all five countries would vote to remain in the EU, with majorities of at least 63 percent.

When British Admiral John Byng failed in his mission to relieve the French blockade of Minorca during the Seven Years War, he was court martialed for negligence and shot by firing squad “pour encourager les autres“. Along the same lines, the Bexit vote acted to discourage other Euroskeptics from going down the same road. That’s why I believe that the Brexit vote lessened the political risk to Europe, contrary to the claims by Stratfor, Jim Rogers and others.

The real lesson of Brexit disarray and the difficulties of the process is to serve as a lesson for Euroskeptics: pour encourager les autres.

Another high-quality analysis, for which I thank you, Cam.

Whether or not Brexit gets completed, the EU is in dire trouble due to economics, not the political issues you cover in your post. Nothing wrong with your political logic, but it isn’t what is important.

Essentially, Europe collectively (not every country, but in the aggregate) spends much more than its income, and keeps borrowing the difference. If it (technically “they”) borrowed from actual savings from people who didn’t spend their entire income, the interest expense would consume most of their budgets. Instead, the central bank creates money out of thin air and uses it to buy the newly created debt.

Investors, especially pension funds and insurance companies panicked by yields that keep dropping below what they need to meet future obligations, have rushed into whatever stray bonds that the central bank hasn’t already bought.

And this is while their economies are staggering along relatively flat. Should they go into a recession, which looks likely in the next year or two, government tax revenues will drop, deficits will soar, and the central bank will not only have to buy more bonds to cover that, but will probably start issuing free money into everyone’s accounts in a futile attempt to get the economy back to mediocre.

At some point, citizens will say to themselves, why do I hold Euros when the central bank keeps creating so many more of them? Maybe I should trade them in for something more scarce that the government isn’t capable of manufacturing–anything really, whether an asset like property or shares of a solid company, or as we saw in the last year when the Venezuelan central bank let its money printing get out of hand, toilet paper, food, and other consumer goods. Inflation takes off, bonds collapse, and troubles of all kind ensue.

This has happened constantly throughout history, going back centuries, whenever a country tries to spend more than it earns, and print the difference. To do that is to fight a losing battle against reality, and that is what Europe is doing. Reality is you must produce something to consume it; if you keep consuming more than you produce, sooner or later whoever is covering your extra spending will balk at letting you keep doing that.

The UK isn’t much different in its policies, and will probably suffer the same fate whether it stays or leaves; its only edge is that its economic policies are slightly less idiotic than those of Europe, although with the current head of the BoE it is closing that gap. At least its government is less parasitic than that of the EU; Brexit was as much about escaping the rising oppression from the bureaucrats in Brussels as anything else, and is a good move for that reason alone.

As for Scotland wanting to leave, good luck with that. Scotland likes to get free money from the EU, but its primary source of free money is the English taxpayer. Had the referendum a couple years ago on Scotland leaving the UK succeeded and it were its own country now, the oil price collapse would have it running deficits that would make Greece look like a mercantilist power. Unless oil goes way over $100 and stays there, it is completely unviable as an independent country. Sure, it can do what the EU is doing, which is spend what it wants and print money to pay bills, but how did that work out for Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Weimar Republic, and France in the 1790s, among others? See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Assignat for some history.

Regarding the British Columbia tax on property purchases by foreigners, Florida charges a 10% tax when a foreign-owned property is sold.

Canada and the U.S. are large land masses with a high degree of regional economic disparity which is partly compensated by a federal system of transfer payments. The European Union is a large land mass with a high level of regional disparity but it is not a federation and does not have the power to tax and redistribute wealth. It seems to be a case of wanting to have your cake and eat it too. It is hard for me to imagine European politicians agreeing to surrender some of their national taxation powers to a central authority.

I tend to agree with the view that the simultaneous strength of the US dollar, stocks and bonds is an abnormal condition resulting from funds leaving Euroland rather than an indicator of the US economic health. As the saying goes, ‘This is unlikely to end well.’ I am using the current market run-up as an opportunity to increase cash and decrease risk assets.

I’d like to add one more thing, more directly related to the stock market. You’ve been pretty bullish for the last year or so at least, Cam, and have been quite correct, not that the market is way up, but it is up. I think you have been right for many good reasons, mostly involving technical analysis, but often right for some wrong reasons having to do with economics. You seem to think that there is a strong connection between the stock market and the economy, and that the prospects of a stronger US economy, however far fetched based upon the guesses of analysts who are proven ignoramuses, is bullish for stocks. This belief in strong economy = strong stock market could lead you astray in the future.

The steady increase in stock prices in recent years is NOT a consequence of a great, or even good economy, the occasional positive appearing (after bogus seasonal adjustments) labor statistic to the contrary notwithstanding. Stock prices have been going up for one main reason – the Fed and other central banks are not printing up new shares of these companies, while they are creating new money and credit to buy the shares.

People will always trade in what is becoming, or is likely to become, more abundant for something that is becoming relatively scarcer. The near 0% interest rates make it easy for any large company whose earnings are under or barely performing (i.e., most of them) to sell debt and use the proceeds to buy back their shares to make up for their lack of earnings growth.

So central banks keep creating new money, companies keep reducing shares outstanding. Which would you rather have, what is becoming a glut or what is becoming relatively scarce? Investors keep trading in their cheap-to-borrow dollars for shares. That is why we have had a bull market. It is actually just a mild version of what Venezuela and Argentina experienced in recent years, where their economies collapsed under socialist, money printing governments, but their stock markets soared as people were desperate to trade in their increasingly worthless currencies for anything not nailed down. You might want to consider looking at our stock market from that perspective.

Hear, Hear!

If not for monty python i wouldn’t know there’s a thing between the French and the English. Explains Quebec in Canada. Thanks for the macro update.

Thank you , Cam for the way you are sending emails with your inner trader moves. Very helpful for someone not able to watch markets all day.

Until recently, Canadians could not purchase out of province farmland The rules, were changed in the last few years which allow Canadian citizens to buy land outside their province. It is interesting to see that America allows farmland purchase regardless of citizenship. Non-Canadians are allowed to purchase 20 acres of farmland last I checked. So much for free markets, and free movement of capital. I do not know if such limits on farmland purchase are in violation of NAFTA.