I have long had much respect for the folks at Lombard Street Research (LSR) for their unusual non-consensus calls. Back in the days of the Tech Bubble when everyone was focused on the likes of Cisco Systems, Lucent, Nokia and other technology darlings, they had said “watch China” as the next engine of growth. That turned out to be the Big Call that made me forever remember them.

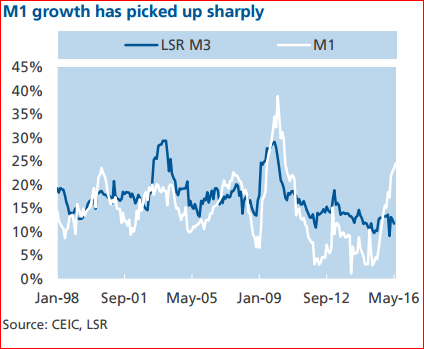

It was therefore with great interest when a Bloomberg story came across my desk indicating that LSR believed that China may be in a liquidity trap. While Chinese M1 growth has been picking up sharply, LSR`s estimate of the growth the broad money M3 has been slowing, which led to the conclusion of a possible liquidity trap.

Here is LSR analyst Michelle Lam:

In a research note published on Monday, she writes: “Over the past two quarters, the PBOC has injected liquidity in excess of capital outflows. But our measure of broad money, which is the best indicator of overall monetary conditions, has deteriorated on a year-on-year basis, and fell below its level in 2013-14 and the government’s target.”

Lombard’s ‘M3’ calculation uses the official, so-called ‘M2′ measure, which is a broader measure of money than what’s known as M1, since it includes time deposits as well as cash and current deposits. In order to calculate M3, Lam adds in deposits that are excluded from mere M2, in addition to banks’ stock of bonds, and foreign liabilities.

The monetary picture is complicated further by the fact narrow money growth, or M1, has continued to soar in recent months, diverging with broad money growth.

Lam reckons the private sector is becoming increasingly unresponsive to M1 growth, with it either hoarding liquidity in deposits or deploying it to repair balance sheets.

“The divergence between narrow and broad money growth just highlights how difficult it has become for Beijing to generate growth by throwing money at firms that are unwilling to invest. Stimulus has boosted growth but has few second-round effects, and money is just not being passed around,” she says.

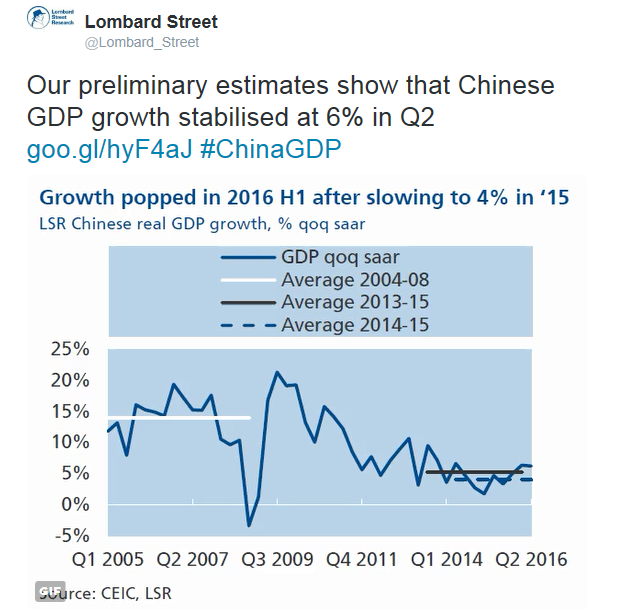

Indeed, LSR`s estimates of Chinese GDP growth has rebounded and now holds steady at about 6%:

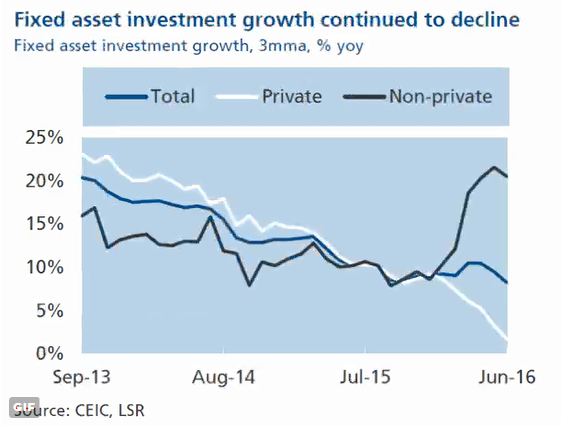

…but growth was propped up by the same-old-same-old investment by State Owned Enterprises (black line) while the private sector (white line) has pulled back:

The latest round of debt-fueled investment driven growth have led many analysts to wonder how long Beijing can continue to play the game of artificially boosting growth as it faces diminishing returns to each yuan of stimulus (via Reuters):

Analysts say that determination has come at the cost of a damngerous rise in debt, which is six times less effective at generating growth than a few years ago.

“The amount of debt that China has taken in the last 5-7 years is unprecedented,” said Morgan Stanley’s head of emerging markets, Ruchir Sharma, at a book launch in Singapore. “No developing country in history has taken on as much debt as China has taken on on a marginal basis.”

While Beijing can take comfort that loose money and more deficit spending are averting a more painful slowdown, the rapidly diminishing returns from such stimulus policies, coupled with rising defaults and non-performing loans, are creating what Sharma calls “fertile (ground) for some accident to happen”.

From 2003 to 2008, when annual growth averaged more than 11 percent, it took just one yuan of extra credit to generate one yuan of GDP growth, according to Morgan Stanley calculations.

A new definition of Money

While these developments are worrisome, let me my two cents worth to the data. As someone of Chinese extraction, I can personally attest to the fact that there is a special affinity in Chinese culture to property investment.

The Chinese attitude towards property and the behavior around property is foreign to western culture. As the property bubble grew over the years and analysts wrung their hands over vacant see-through buildings (and therefore billions and billions in non-performing loans), there was a mitigating factor that the Chinese viewed real estate as a store of wealth – call it M3*. In fact, some preferred to leave apartments bought as investment vacant, much as a coin collector might view an un-circulated coin as more valuable. Moreover, the property tax regime encouraged this kind of investment behavior, as property taxes tended to be levied upon sale, rather than as a “wealth tax” for city services as they are in the west.

This attitude towards real estate can also be seen in banking practices. Rather than lend on the ability to service cash flow, as is practiced in the west, Chinese lenders tend to lend on asset value. That’s because accounting statements can be fudged, but asset values are *ahem* solid.

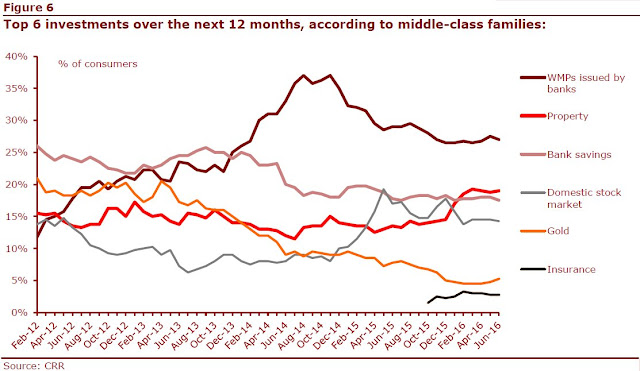

Callum Thomas documented the Chinese attitude towards investment preferences. As the chart below shows, bank deposits and WMP have tended to take the lead, largely because of the minimal investment size required. However, property (orange line) has held steady at about 15% over time.

I would therefore argue that in China, property is a form of money. In light of LSR’s liquidity trap thesis, monitoring what happens to property as money growth (M3* = M3 + real estate) is an important concept in determining the future path of the Chinese economy.

Assessing downside risk

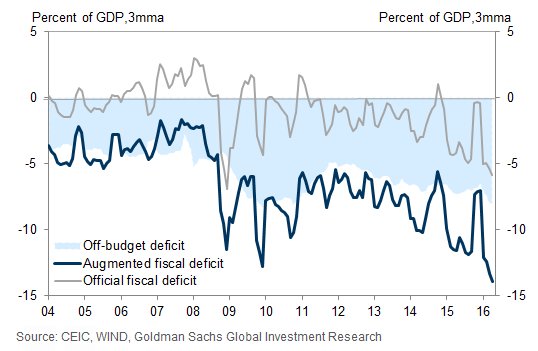

Recently, alarm bells have been ringing over the outlook for China again. Goldman Sachs recently warned that China`s augmented fiscal deficit has ballooned to 15% of GDP.

These signs of sputtering growth and an economy that is becoming less responsive to official stimulus are worrisome signs. These are indications consistent with the Michael Pettis thesis that China has about two years left before it must face some painful adjustments (see How much “runway” does China have left?).

A new monetary framework

The big macro question then becomes, “Is China on the edge of another crisis?” To answer that question, the combination of LSR’s liquidity trap thesis and my observations about property as a form of money leads me to believe that M3* will be an important tool to measure the outlook for China.

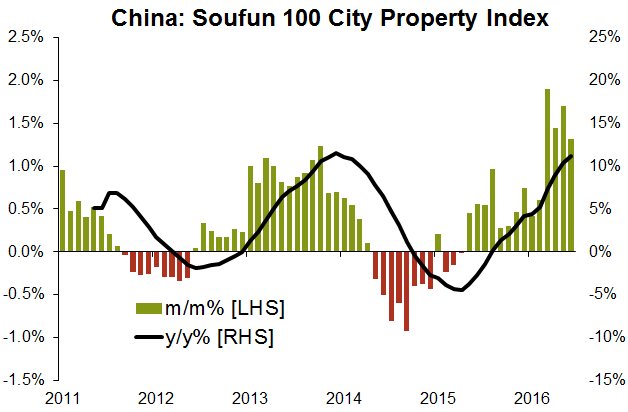

So what’s happening to Chinese property? Callum Thomas recently highlighted the continued improvement in Chinese real estate prices. Apocalypse later, right?

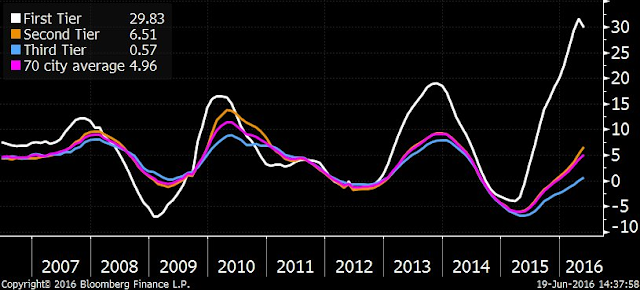

Not so fast! Dissecting the property market data further, Tom Orlik found that Tier 1 prices were starting to wobble, but the other cities were enjoying health gains. While the real estate market appears to be healthy on the surface, the weakness in Tier 1 cities is something that needs to be watched carefully.

Tactically speaking, my conclusion is, “So far, so good.” Despite the apparent liquidity trap, the risk of imminent risk of collapse is minimal at the moment. However, the health of the Chinese property market will have to be watched carefully in the future.

Nice macro view. Thanks.

Werewolves in a Moonless World

Sorry to change the subject but this morning’s bland GDP number just reinforces the ‘lower for longer’ theme. David Rosenberg commented on the yield curve in his newsletter as to whether it was predicting a recession coming. Cam had a post about this a few weeks ago. Here is my email message to him about that plus I took the Moonless World analogy further (too far??!! LOL)

In the Moonless World (Central Banker, the Moon, absent) the yield curve doesn’t predict like it used to.

When there was a Moon, short rates went up more than long when the economy was picking up momentum. Animal spirits kept the economic momentum tide rising and short rates going up until the Moon came into play and the cycle peaked and the tide went out.

Now in a Moonless World, short rates are zero or lower and the yield curve flattens because long rates decline (not short rates rising!) due to animal spirits hibernating not rising. So the flattening means the exact opposite of what it did previously.

Text books didn’t contemplate this. Will this cause a recession as animal spirits go into a deeper sleep? Will animal spirits come out of hibernation and start borrowing this cheap money being thrust at them and cause an inflationary, higher interest rate, risky boom? Media commentators love speculating on these exciting extremes.

Let’s take the Moonless example a step further. The human actors in the global economy are like bipolar werewolves. When the Moon was full, they romped in the woods with huge energy. It was party time but very dangerous. When the Moon waxed, their energy level got depressed, also dangerous in a different way. In a Moonless World, the werewolves are on lithium. That moderates the mood swings to almost flat. We are uncomfortable being around them in this new state because we fear they will swing to dangerous bipolar extremes, both of which are dangerous. But no, it isn’t dangerous. The lithium works. The economic swings of the general economy in the Moonless World are minimal. A bit of general weakness doesn’t mean the werewolf will go into depression. A bit of strength doesn’t mean galloping, blood thirsty in the woods. The lithium is at work. The bipolar actors are tamed.

In this Moonless World, industry sectors can have their own supply/demand business cycles and bull and bear stock market cycles. The general stock market cycles will get progressively less swingy as investors start realizing that the bipolar extremes they were accustomed to, no longer apply. The stock market gets progressively more boring with predictable yield trumping exciting earnings as the measure of success. The VIX cardio pulse slows and swings less. Media commentators will be hoping that the werewolves stop taking their lithium because it sure was a whole lot more interesting when the bipolar mood swings were intense.

The Moonless World with tame economic actors is a place when one can prosper at a measured, boring, and safer pace.

“The VIX cardio pulse slows and swings less. ”

Indeed….a more detailed article on our recent two weeks is here: https://lplresearch.com/2016/07/29/welcome-to-the-most-boring-market-in-21-years/

“…the intra-day high and low range over the past 11 days has been only 0.92%, the tightest range ever in the 45 years of available data. Put it this way: 30 of the first 31 days in 2016 had a larger one day range (0.92%) than the past 11 days have had.”

To close with a hat tip to Cam’s Occidental theme: we live in interesting times!!

…I occidentally forgot the “non” in front of Occidental….I see a trivial pursuit question in there somewhere for sure 😉

Ken, thanks for sharing your unique views with us. It’s a positive view but discouraging at the same time. With less volatility, more focus on longer term dividend track record, premium on low volatility, proliferation of etf investing, full market multiples forcing others to start focusing on whatever miniscule market inefficiencies there still is, massive money on the sidelines.. seems like the market is getting more efficient. Hoping that’s not the case.

I like the idea that international investing requires understanding cultural differences in money and finance. Thanks for an interesting article.

Thanks for the article on China. Yes, I note that China has so far being on an unprecedented borrowing binge (give or take 15% of GDP). The more “connected” of our Chinese friends are exporting $s to the US, through their children who we see are buying expensive European automobiles (Porches and BMWs feature high), college education on private tuition costs and expensive US real estate. I observe these children are backed by Texas sized parental river of money. I have wondered over the past few years as to why, and the answer is simple. Before the US $ becomes more expensive in Yuan terms or before China puts capital controls, it would be wise to siphon off as many US $s to safe haven outside China (destination of such capital is USA, that I can verify, but also Canada, London and Australia from what I hear). Cam’s analysis supports my conclusion. As to property investments in China, if real estate buying in China is supported by low debt, it may not loose much (?) value, but it is difficult to make this statement with complete confidence. If say as an example, 60-80% of new real estate in China is being purchased as investment, panic selling will eventually take its toll, unless central bank (PBOC) intervenes, much like the US fed did circa 2008, and stave of deflation. Huge leverage in US property market saw to it that the bubble collapsed even when outstanding delinquent loans were less than 10%.

Where China ends, and what it means to the US and rest of the world is not that easy to estimate. Ruchir Sharma’s article in the Wall Street Journal from Friday, 7-29-16, talks about how the US fed is now beholden to a globalized economy. http://www.wsj.com/articles/the-dollarand-the-fedstill-rule-1469748023

My gut feeling is that a moonless world would be deflationary (and asset prices volatile) to the global asset prices. Under such a scenario, the moon will have to rise and shine brighter and try and create inflation. As BOJ is now buying ETFs in the open market (http://www.reuters.com/article/us-japan-economy-boj-idUSKCN1090AY?il=0), one day it may expand its policy and buy global stocks or Toronto real estate or SPY. Perhaps the US fed may be forced to relax monetary policy even further. At the risk of sounding a scaremonger, this whole experiment of easy money policy is starting to feel like demise of fiat money. For those interested, here is a book that I found difficult to read, but those of who know history, and German geography, especially European history, may find it easier to read:

When Money Dies: The Nightmare of Deficit Spending, Devaluation, and Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany

I found this book to be a difficult read perhaps because it is verbatim translation of the original into English (not sure about this). The conclusions however were apocalyptical. For those of who have read this book, or would read this book I would love to hear their take, on how far the conclusions of Weimar Germany are applicable to today’s world. I understand that with the background of war, Weimar Germany is no analogy to today’s world where there is no specter of war causing demise of fiat money. However, net effects are the same, devaluation of fiat money. Thanks.

Hi D.V.

I stumbled across an excerpt from the book you refer to….wild times indeed:

“The fall in the mark, the memorandum continued, was gradually wiping out the middle classes, the value of whose investments was quickly disappearing. A holding of 1 million marks in German War Loan, which had corresponded at the time of purchase to about £45,000 of British War Loan, now had a sterling value of about £1,000, ‘and even its internal purchasing power is not more than £3,000 and is rapidly falling’. A German pensioner with an income of 10,000 marks before the war compared favourably with an English pensioner with an income of £500.

Now, the sterling value of his pension was £10 and its purchasing power less than £30. Insurance policies, furthermore, were worth less to the holder or his widow than the annual premium which he had put by each year out of his hard earned savings.

Blackett noted that the rent restriction Acts hit much the same classes, who were ‘forced to starvation in order to subsidise the German workman’s wages and the employer’s profits’. The bread and rail subsidies, financed by inflation, combined with the rent restriction, enabled the foreigner to buy German goods well below world prices and, if he lived in or visited Germany, to travel, eat and occupy houses at ridiculously cheap rates. ‘A gradual process of buying up and carrying off Germany’s movable capital, secondhand furniture, pianos, etc., is taking place at the expense of Germany as a whole.’

Foreigners were also buying up real property and interests in factories and all kinds of businesses. To some extent this was at the expense of the workman whose wageslagged behind the climbing cost of living, but it was mainly at the expense of the middle classes whose capital was destroyed and largely exported. The exporting industrialists could just keep their heads above water, Blackett thought, but the others making goods out of partly imported material could not possibly replace it with a continually rapidly falling mark.”

Cheers, Motu

Cam,

What role if any does the great amount of money invested in hard assets outside China play in the overall picture of stabilizing China in the future? Living in Vancouver, it’s said a lot of that money has gone into commercial and residential real estate. But Chinese money has also gone into the same kind of assets in many other countries. If the **** were about to hit the fan, wouldn’t the government there be able to rely on the citizenry outside China and on their assets?

Considering billions and maybe trillions have been moved out, far surpassing the $50,000/year allowance, this must be part of China’s strategy?