Stock markets were rattled by the Fed’s hawkish tone in the wake of the FOMC meeting. Markets took a risk-off tone, but Jerome Powell walked back some of the hawkishness during his Congressional testimony the following week. The Fed Chair stuck to his familiar refrain that inflation is transitory, dismissed the idea of 1970s-style inflation as “very, very unlikely”, and unemployment is transitory but labor markets need continued support.

In response, the markets rebounded and prices largely made in round-trip in pricing in most asset classes. But in order for the markets to continue accept the Fed’s narrative, the next challenge for the Fed is cost-push inflation in the form of wage pressure. This will become more apparent with the release of the June Employment Report in the coming week.

The Fed’s dilemma

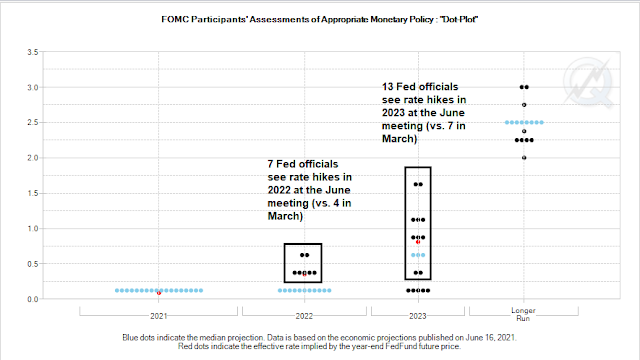

The June FOMC meeting produced several changes of interest. The Fed stated that downside risks were diminishing as the vaccination rate rose. More importantly, it raised its inflation projection for 2021 and the “dot plot” projected a rate liftoff in 2023. To illustrate the hawkish turn, seven Fed officials see rate hikes in 2022, compared to four at the March FOMC meeting. 13 see rate hikes in 2023, compared to seven at the June meeting.

In the wake of the FOMC meeting, Joe Wiesenthal at Bloomberg openly wondered if the Fed is pivoting towards its traditional anti-inflation role:

There is a sense in which the recent months of data have activated the inflation-fighting red blood cells at the Fed. During the press conference, Powell was largely optimistic about the trajectory of the economy. But in terms of risks, he’s clearly more concerned about an inflation overshoot than an employment undershoot. This is a change after months and months of being more concerned about weak labor markets. And now there’s some debate about whether the new dots fit with the framework set out at Jackson Hole last year, where the Fed indicated plans to wait to see signs of sustained inflation before raising rates.

In reality, a divide is opening at the Fed. The hawkish tone of the FOMC is probably attributable to some Regional Fed Presidents who are seeing price pressures in their districts. The core voters at the Fed, the Fed governors, and New York Fed President Williams, are continuing to counsel patience.

Lisa Abramowicz at Bloomberg summarized the policy dilemma:

In some ways, the Fed has trapped itself in a tight corner that will prove difficult to exit successfully. It wants to see inflation pick up, and yet its every move has unprecedented ramifications for a world awash in debt. If inflation runs too hot, traders will worry about a fast round of tightening that will torpedo growth and puncture asset-price valuations. If central bankers raise rates sooner, traders will price in a slower, cooler longer-term expansion.

Investors have to recognize that the Fed has to contend with two kinds of inflation risks. There is the inflation of a transitory nature attributable to supply chain bottlenecks, such as rising used car prices and airfares. The more insidious risk is a 1970’s style price spiral, where price pressures in one part of the system causes firms to pass on their cost increase, which prompts workers to demand higher wages, which raises further cost pressures for firms, and so on. In the past, the Fed has broken cost-push inflation threats by breaking any potential inflation spiral at the wage pressure link. As soon as wage increases start to get out of hand, the Fed has tightened in order to rein in inflationary expectations.

Will the Powell Fed follow the same path? That’s the next policy challenge.

How broad and inclusive?

The NY Times reported that Powell walked back his hawkish stance at his Congressional testimony, but he qualified his remarks by embracing a “broad and inclusive” labor market recovery.

Speaking before House lawmakers on Tuesday afternoon, Mr. Powell emphasized that the Fed was looking at maximum employment as a “broad and inclusive goal” — a standard it set out when it revamped its policy framework last year. That, he said, means the Fed will look at employment outcomes for different gender and ethnic groups.

“There’s a growing realization, really across the political spectrum, that we need to achieve more inclusive prosperity,” Mr. Powell said in response to a question, citing lagging economic mobility in the United States. “These things hold us back as an economy and as a country.”

The Fed cannot solve issues of economic inequality itself, he said. Congress would need to play a role in establishing “a much broader set of policies.”

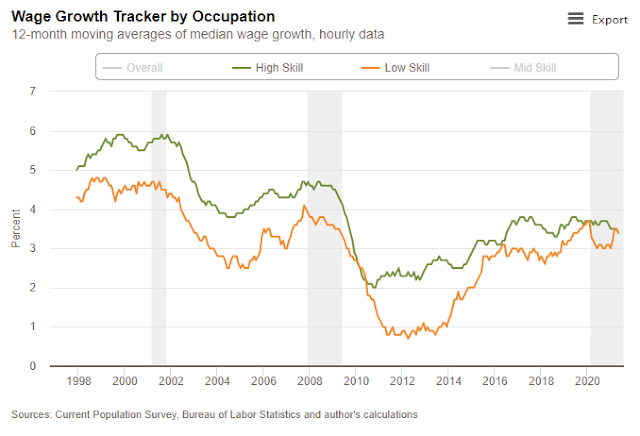

How broad and inclusive? The Atlanta Fed’s Wage Growth Tracker reported that low-skilled workers have already made up much of the pre-pandemic wage growth losses.

Viewed through the education level prism, which is another proxy for wealth inequality, the wage growth of workers with a high school education was steady while wages of those with bachelor degrees decelerated during this period. Amid the cacophony of complaints from the small business owners at NFIB about the inability of employers to fill job openings, how determined is the Fed prepared to address the inequality problem?

Low-wage workers found something unexpected in the economy’s recovery from the pandemic: leverage.Ballooning job openings in fields requiring minimal education—including in restaurants, transportation, warehousing and manufacturing—combined with a shrinking labor force are giving low-wage workers perks previously reserved for white-collar employees. That often means bonuses, bigger raises and competing offers.

Average weekly wages in leisure and hospitality, the sector that suffered the steepest job losses in 2020, were up 10.4% in May from February 2020, Labor Department data show, outpacing the private sector overall and inflation. Pay for those with only high school diplomas is rising faster than for college graduates, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

“It’s a workers’ labor market right now and increasingly so for blue-collar workers,” said Becky Frankiewicz, president of staffing firm ManpowerGroup Inc.’s North America operations. “We have plenty of demand and not enough workers.”

For years, factory jobs paid significantly more than those in many other fields, especially for less-educated workers. That is changing, according to economists, manufacturers and federal data.

[Furniture maker] Haworth has raised wages at factories near its Holland, Mich., headquarters to $15 an hour, plus another dollar for the night shift. It has amenities like a 24-hour gym as well as annual Thanksgiving turkey and Christmas gift giveaways. Haworth still isn’t finding enough workers. That could hold back production at a time of red-hot demand for furniture, vehicles and many other consumer goods.

Some workers recently left Haworth’s factory in the nearby town of Ludington for hospitality jobs, Ms. Harten said. Haworth is advertising assembly jobs for $14 at that facility—the same starting pay rate at a nearby Wendy’s restaurant. “Manufacturing can be taxing,” said Ms. Harten, who also believes enhanced Covid-19 unemployment benefits are discouraging some people from taking open jobs.

Because most factories have been fully operational since last summer, hotels and restaurants are doing comparatively more hiring now as patrons return as Covid-19 restrictions lift. Paul Isely, a professor at Grand Valley State University in Allendale, Mich., who studies the region’s economy, said that manufacturers face more pressure to hold down wages than some service employers because they compete with factories around the world rather than restaurants around the corner.

One simple explanation is that enhanced unemployment benefits are keeping workers at home and decreasing the worker supply. But Indeed’s chief economist Jed Kolko pointed out that job “search activity remains below national trend in twelve states that prematurely opted out of enhanced federal UI benefits on June 12 or 19”.

The rise of low-wage workers is not strictly an American phenomenon. The Economist reported that the same thing is happening in the UK. The British fiscal response to the pandemic was to provide wage subsidies to employers to keep workers on the payroll. By contrast, the US response was to boost unemployment benefits. In both cases, wage pressures rose at the low end. Therefore the narrative of the lazy worker enjoying Uncle Sam’s largesse at home can’t be the main reason for worker shortage.

The most likely explanation is a combination of pandemic fears, childcare availability for women, and premature retirement. Goldman Sachs estimated that as many as 1.2 working Americans retired early over the course of the pandemic.

It’s also unclear how the Fed plans to resolve the conflict between its full employment and price stability mandates given that wage pressures could spark a potential cost-push inflationary spiral. Investors are well-advised to monitor the evolution of wage pressures after each Employment Report and the body language of Fed officials in response to rising employee compensation. Moreover, wage pressures are occurring in an environment where progress in initial jobless claims have flattened out. This has the potential to put the spotlight on the Fed’s dual mandate of price stability and maximum employment.

The market response

The bond market’s response to the Fed’s qualified hawkishness has been a twist in the yield curve. In the short end, the spread between the 2-year and 3-month yield steepened. The belly of the curve tells a different story. The 2s10s spread flattened. I interpret this to mean that the 2-year is anticipating the Fed will raise rates, but the 2s10s is signaling slowing growth further into the future. The two yield curves have usually moved in tandem in the past.

The sample size is extremely limited as there was only one instance when the two yield curves have diverged since 1990. The S&P 500 underwent periods of sideways consolidation in 2011, but that was a year marked by the Greek crisis in the eurozone. We are really in uncharted waters.

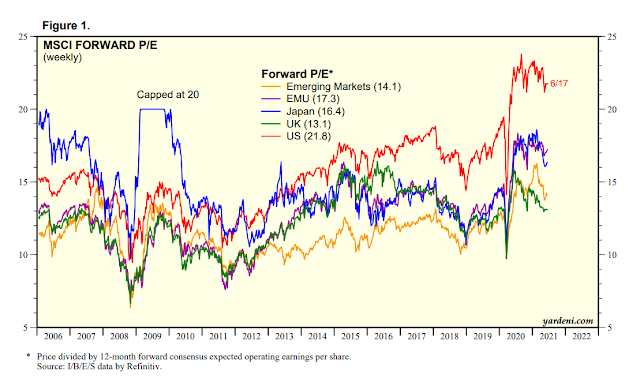

Investors may find better equity opportunities in light of the valuation gulf between US and non-US equities.

That said, let’s not get ahead of ourselves. The Fed is only talking about when and the process of tapering its QE program. Historically, the 10-year Treasury yield has fallen whenever the Fed has tapered its QE program. The record for stocks is mixed. The S&P 500 traded sideways during the QE1 and QE2 tapers, but rose during the QE3 taper.

That’s even before the Fed hikes rates, which is at least two years in the future. Ryan Detrick of LPL Financial pointed out that stocks have continued to advance in the past at the first hike.

Relax. The bull isn’t dead. It may take a breather, but there are more gains ahead for equity investors.

Cannot get my head around why bond yield declines when Fed tapered QE? It feels counter-intuitive. Fed buying fewer bonds reduces the demand. Hence bond prices fall and yield rise.

Is it a case of ‘buying the rumor and sell the news’ i.e. Fed would have communicated and prepared the market well in advance of the

actual tapering news such that the market has already priced in the effect of taper (over-shoot on the rising bond yield). When the tapering new finally eventuates, the over-sold bond price (higher yield) reverses.

Here is the reason why: With less fed support, one anticipates a slowing in the economy. A slow growth economy equates to taking less risk in stock market, hence money goes into bonds. The logic is not intuitive and made to fool most investors.

Here is the caveat: Most money is made once Fed loosens its money strings. Follow the money.

Bottom line, taper means, a bond rally!!!!!!! The caveat to this statement is “all else remaining constant”. “All else” in this case is inflation. If inflation cracks higher this time, we could see a bond market sell off, like you are suggesting.

Since 1982, we are expecting a bond market sell off. Has only happened in 1994, I think in any significant manner and this year.

Cam, are you still long Commodities/Mining-Stocks? Is this an intermediate term investment?

Short answer is “yes”.

Thank you

Most classic portfolio ideas suggest inclusion of commodities as a countercyclical asset, say a 5 % (to 10 ?) allocation.