In his latest letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, Warren Buffett reported that even Berkshire’s largest publicly listed holding is asset-light Apple, and Berkshire is a very asset-heavy company. Its two major holdings are railroad BNSF and electric utility BNE, which has a large capital project to upgrade the electrical transmission grid in the western US, due to be complete in 2030.

Recently, I learned a fact about our company that I had never suspected: Berkshire owns American-based property, plant and equipment – the sort of assets that make up the “business infrastructure” of our country – with a GAAP valuation exceeding the amount owned by any other U.S. company. Berkshire’s depreciated cost of these domestic “fixed assets” is $154 billion. Next in line on this list is AT&T, with property, plant and equipment of $127 billion.

Our leadership in fixed-asset ownership, I should add, does not, in itself, signal an investment triumph. The best results occur at companies that require minimal assets to conduct high-margin businesses – and offer goods or services that will expand their sales volume with only minor needs for additional capital. We, in fact, own a few of these exceptional businesses, but they are relatively small and, at best, grow slowly.

Efficiency vs. resiliency

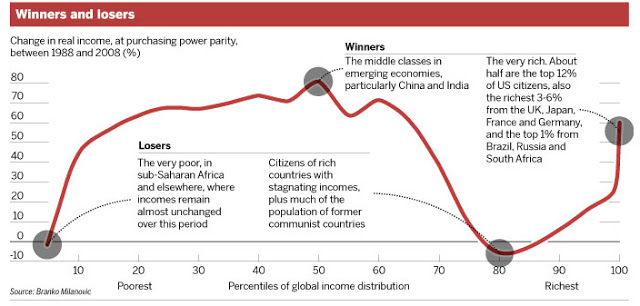

At the heart of the asset-light platform company’s kryptonite is a tradeoff between efficiency and resiliency. The offshoring boom was built upon the idea of efficiency. Perform all of the high value-added design work at the home office, and outsource the lower value-added production offshore. This focus on efficiency globalized manufacturing supply chains and sparked the emerging market boom illustrated by Branko Milanovic’s famous elephant graph. The winners were the middles classes in the EM economies and the very rich, who engineered the globalization initiative. The losers were the inhabitants of subsistence economies, who were not industrialized enough to take part in the boom, and the workers in industrialized countries.

Fast forward to today, what have we learned about the tradeoffs?

The new OPEC

Consider the vulnerabilities exposed by the combination of the Sino-American trade war and the pandemic in semiconductors. Most American semiconductor companies have moved to the fabless manufacturing business model, as described by Wikipedia.

Prior to the 1980s, the semiconductor industry was vertically integrated. Semiconductor companies owned and operated their own silicon-wafer fabrication facilities and developed their own process technology for manufacturing their chips. These companies also carried out the assembly and testing of their chips, the fabrication.

As with most technology-intensive industries, the silicon manufacturing process presents high barriers to entry into the market, especially for small start-up companies. But integrated device manufacturers (IDMs) had excess production capacity. This presented an opportunity for smaller companies, relying on IDMs, to design but not manufacture silicon.

These conditions underlay the birth of the fabless business model. Engineers at new companies began designing and selling ICs without owning a fabrication plant. Simultaneously, the foundry industry was established by Dr. Morris Chang with the founding of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (TSMC). Foundries became the cornerstone of the fabless model, providing a non-competitive manufacturing partner for fabless companies.

Here is the tradeoff. Bloomberg recently reported that manufacturers have discovered that a chip shortage has made them hostage to Korean and Taiwanese semiconductor companies.

There’s nothing like a supply shock to illuminate the tectonic shifts in an industry, laying bare the accumulations of market power that have accrued over years of incremental change. That’s what’s happened in the $400 billion semiconductor industry, where a shortage of certain kinds of chips is shining a light on the dominance of South Korean and Taiwanese companies.

Demand for microprocessors was already running hot before the pandemic hit, fueled by the advent of a host of new applications, including 5G, self-driving vehicles, artificial intelligence, and the internet of things. Then came the lockdowns and a global scramble for computer displays, laptops, and other work-from-home gear.

Now a resulting chip shortage is forcing carmakers such as Daimler, General Motors, and Ford Motor to dial back production and threatens to wipe out $61 billion in auto industry revenue in 2021, according to estimates by Alix Partners. In Germany, the chip crunch is becoming a drag on the economic recovery; growth in China and Mexico might get dinged, too. The situation is spurring the U.S. and China to accelerate plans to boost their domestic manufacturing capacity.The technological prowess and massive investment required to produce the newest 5-nanometer chips (that’s 15,000 times slimmer than a human hair) has cemented the cleavage of the industry into two main groups: those that own their fabrication plants and those that hire contract manufacturers to make the processors they design. South Korean and Taiwanese companies figure prominently in the first camp. “South Korea and Taiwan are now primary providers of chips like OPEC countries once were of oil,” says Ahn Ki-hyun, a senior official at the Korea Semiconductor Industry Association. “They don’t collaborate like OPEC. But they do have such powers.”

U.S. companies lead the world in designing microchips. But two Asian players, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing (ticker: TSM) and Samsung Electronics (005930.Korea), control manufacturing. The two account for three-quarters of the complex “logic” chips produced globally, and all of the most advanced chips with a thickness of seven nanometers or less, says James Lim, Korea analyst at Dalton Investments.

Intel (INTC), the leading U.S. manufacturer, has fallen off the Asians’ pace, and catching up seems like a long shot. “Semiconductors are the most complex things that humans make,” says Brian Bandsma, emerging markets portfolio manager at Vontobel Quality Growth. “It isn’t something you can solve by throwing money at it.”

The Texas lesson

The pendulum swings back

What is the name of the tailor town in Vietnam?

We all want to know!

BeBe Tailor in Hoi An, which is a small town near DaNang.

https://bebetailor.com/

Is the idea of asset light something new? Hasn’t this being going on for a few decades now? Sure, for Mr. Buffett it may be new. Agree.

The “asset heavy” semiconductor stocks have been outperforming the fabless semiconductor stocks so far.

Monday may go down as peak anti-ARKK, thus marking at least a ST buy point.

A 50/50 bet right now as to whether the NDX resumes its uptrend here. The fact that many traders are calling Tuesday’s action a bear market rally (ie, remain bearish) may provide support in the near term.

Adding to ASHR. This week is probably the time to buy China stocks.

Adding aggressively to NIO/ QS/ PLTR.

Opening BABA.

Adding to XLU (utilities). I think it senses a decline in bond yields.

Adding to EWZ.

Still long QQQ, ARKK strong, XRT also. Awaiting short pause today and UP tomorrow. DIX has moved to neutral reading.

Thanks.

Reopening PICK.

Adding to QQQ.

I am observing 4 h. chart and to be honest I agree with you. My best scenario is to hold QQQ until Friday / Monday – as Friday and Monday are usually strong days.

Today’s retest should set up a more durable rally next week. Right now, anyone fortunate enough to buy into Monday’s selloff is locking in profits.

The 730 am pullback remains intact.

We’re seeing a retest of sorts. In the long run, it will lend support to a reversal to the upside. For now, it’s going to inflict some pain.

Keeping your eyes on the long(er) term is helpful at this point. It’s standard practice for the market to try shaking you out of new positions.

My take-> if you opened positions in growth/innovation in the past two days, there is a decent chance you will see spectacular gains over the intermediate term.

They finally convinced EWZ to join the global rally.

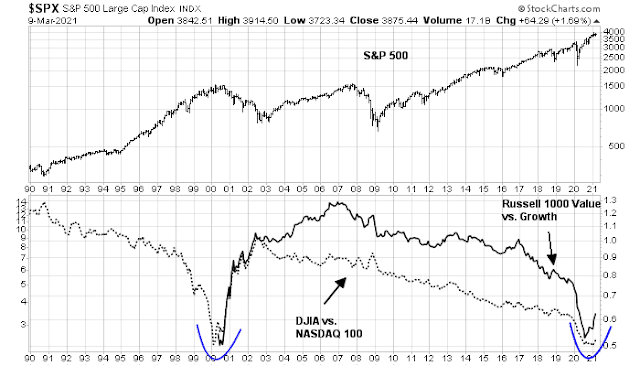

That last chart above, ‘value vs. growth’, and the twenty-year double bottom in the ratio, v. impressive. Who would argue with that?

Short term oversold, but still too much positive ARKK sentiment among among the great unwashed IMO. Wise-guy, cynical twitterites, another story altogether.

Ten year yield into the MOAR (Mother Of All Resistance), looks overstretched, but why should it go down?