Preface: Explaining our market timing models

We maintain several market timing models, each with differing time horizons. The “Ultimate Market Timing Model” is a long-term market timing model based on the research outlined in our post, Building the ultimate market timing model. This model tends to generate only a handful of signals each decade.

The Trend Model is an asset allocation model which applies trend following principles based on the inputs of global stock and commodity price. This model has a shorter time horizon and tends to turn over about 4-6 times a year. In essence, it seeks to answer the question, “Is the trend in the global economy expansion (bullish) or contraction (bearish)?”

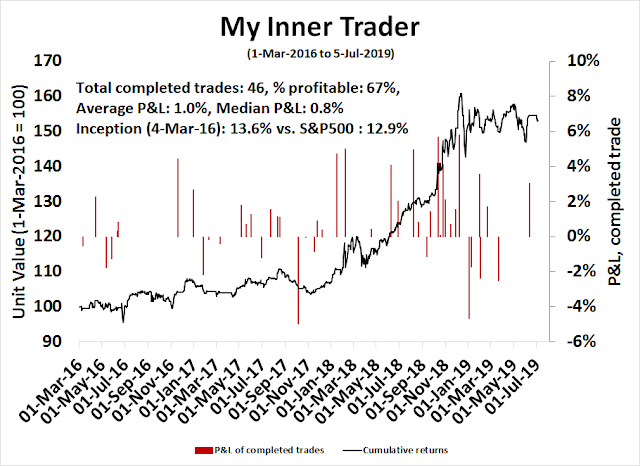

My inner trader uses a trading model, which is a blend of price momentum (is the Trend Model becoming more bullish, or bearish?) and overbought/oversold extremes (don’t buy if the trend is overbought, and vice versa). Subscribers receive real-time alerts of model changes, and a hypothetical trading record of the those email alerts are updated weekly here. The hypothetical trading record of the trading model of the real-time alerts that began in March 2016 is shown below.

The latest signals of each model are as follows:

- Ultimate market timing model: Buy equities

- Trend Model signal: Neutral

- Trading model: Bearish

Update schedule: I generally update model readings on my site on weekends and tweet mid-week observations at @humblestudent. Subscribers receive real-time alerts of trading model changes, and a hypothetical trading record of the those email alerts is shown here.

Buy the ugly duckling?

In the past few weeks, these pages have been all trade war, all the time. While that was not the original intent of this publication, headlines have conspired to turn the focus on the Sino-American relationship. Now that an uneasy truce is in place, it is time to switch gears and turn the spotlight on other unexplored parts of the market.

Finance literature since the Great Financial Crisis has been filled with the imagery of swans. Black swans. White swans. Grey swans. What is missing is the ugly duckling that grew up to be a swan. More importantly, what if an investor could identify an ugly duckling before it becomes a swan?

I have identified such a candidate. The chart below shows the relative performance of US stocks against the MSCI All-Country World Index (ACWI) in black, and the Euro STOXX 50 against ACWI in green. While there is no question that US stocks have been the winners, eurozone equities are in the process of making a broad saucer based relative bottom, and may be poised for a period of outperformance. The relative bottoming process is especially remarkable in light of the current environment of global trade uncertainty, which may be a signal of investor capitulation and the inability to respond to bad news.

Unloved and washed-out

The first prerequisite of any ugly duckling candidate is its unloved nature. As the latest BAML Global Fund Manager Survey shows, managers have replaced what was once enthusiasm with indifference. BAML reported that short eurozone equities is the fourth most crowded trade, and current positioning is 0.9 standard deviations below its long-term average.

The mircale of Europe (and the euro)

For my friends on this side of the Atlantic, file the following story under “why you don’t understand Europe”:

The Vietnam War was a war that scarred the national psyche and dramatically changed the tone of American foreign policy for a generation. If you visit the Vietnam Memorial in Washington DC today, you will find roughly 58,000 names of fallen soldiers from that period. Now imagine if instead of losing 58,000 soldiers, the 2.5 million American soldiers died during the Vietnam War, with many more wounded. For a country like the US with a population of roughly 330 million, that kind of casualty rate would mean virtually every household in America would be touched by combat, whether it’s a father, son, brother, uncle, friend or neighbor. Then 25-30 years later, which is roughly the span between the Vietnam War and 9/11, the country became involved in another conflict with a similar death toll.

Imagine the resulting national trauma.

That’s what happened to many European countries in the First and Second World Wars – and the losses quoted would be roughly what the equivalent losses are for the US on an equivalent per capita basis on par with many European countries. The Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Handbook has documented the financial cost of a century of war in Europe. Here are the real returns to different asset classes in France over the last century. In addition to the human carnage, investors suffered devastating losses during those wars (red annotations are mine).

Here is the same analysis for Germany. In addition to the lives lost, many investors had to contend with the permanent loss of capital. Some of those “risk free” interest rates that may have been in financial models weren’t so free of risk anymore.

The UK fared much better as hostile foreign troops never set foot on its soil. On an inflation adjusted basis, its equity returns were an order of magnitude better than France or Germany.

For comparative purposes, here is the return record of US assets over the same period. Americans were fortunate to have escaped the two world wars with minimal financial damage. The Great Depression caused more equity damage than the wars. The terminal real value of equity investments was three times better than the UK’s results.

So is it any surprise that at the end of the Second World War, the leadership of Western Europe surveyed the carnage and concluded that we can never do this again. Ever. Thus the Common Market, the EEC and later the EU were born. While it was originally structured as a free-trade agreement, the political intent was to bind the two main combatants, France and Germany, so tightly together so that a European war cannot happen again. The political goals of Europe have largely succeeded. Today, if Angela Merkel mobilized the Bundeswehr and told the troops they were going to war against the French, the men would all laugh, have a beer and go home.

That is the miracle of Europe. But peace comes with a cost, and that cost is the unevenness of European integration. Outsiders have viewed the design of the common currency, the euro, with horror because of the lack of adjustment mechanisms between countries, and the lack of political and fiscal integration. Those faults are features, not bugs, of the eurozone. Admittedly, weaker economies such as Italy should never have been allowed into the euro area, but they were in the name of European solidarity.

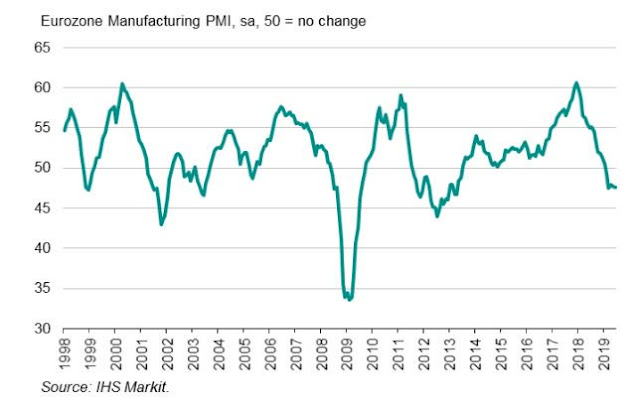

It was therefore no surprise that periodic financial crises erupted, such as Greece. Other peripheral countries have also teetered, and the latest is Italy, which is too big to save and the source of much angst among investors. Today, eurozone manufacturing PMI is signaling a slowdown.

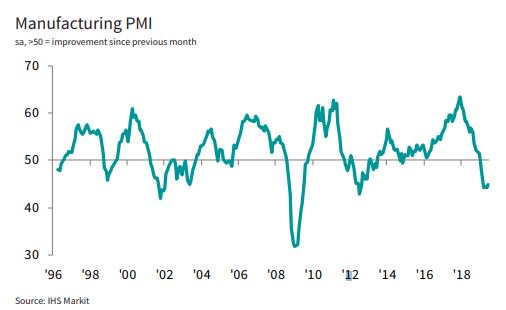

Even Germany, which has been the region’s locomotive of manufacturing growth, is seeing some softness.

It is therefore a puzzle that the Germans are stubbornly sticking to their austerity discipline, when some fiscal stimulus would help the economy, especially when its borrowing costs are negative for German sovereign debt that go out 20 years or less. Neighboring Austria has taken advantage of the low interest cost environment by floating a 100-year bond with a 2.1% rate last year, and it is returning to the market with another issue with a 1.2% coupon.

Why not Germany, whose growth would renew the entire region?

Good news ahead

Here is the good news. Europe has not only held together, but it has become stronger in the post-Brexit environment, as an article in The Economist explained:

The crises of the past decade have tested the union and found it wanting. They have also revealed its resilience. Whenever it came close to breaking up, its institutions and governments took painful and politically contentious decisions to hold it together. The European Central Bank, for example, prevented the euro’s collapse with a promise to do “whatever it takes” that horrified thrifty Germans—who nevertheless, because of the value they placed on the union’s survival, stuck with the strategy. Since the Brexit referendum in 2016 the EU’s response to the once-unthinkable shock of a large nation deciding to leave has both illustrated and strengthened its underlying cohesiveness.

Possibly as a result of having peered over more than one brink, possibly as a result of an increasingly alarming world beyond their borders, Europeans are regaining some faith in the EU. In a survey of union-wide opinion taken last September, 62% of respondents said that membership was a good thing, the highest proportion since 1992. Only 11% said it was a bad thing, the lowest rate since the start of the financial crisis (see chart 1). The Brexit mess has doubtless put off other would-be leavers; the parties which once promised referendums on leaving in France and Italy have quietly dropped the idea. But the rise in support began in 2012, four years before Britain’s referendum.

One of the problems with European integration is the vastness of Europe. Residents have no cultural connection to Europe. There is no sens of volk, but European politicians have arrived at a new paradigm: “The Europe which protects”.

A visitor from Mars—or, for that matter, Beijing or Washington—might see further integration as a prerequisite for sorting out such problems. But Europe is not America or China. It is a mosaic of nation states of wildly varying size and boasting different languages, cultures, histories and temperaments. Its aspiration to be as democratic as a whole as it is in its parts is profoundly hampered by the lack, to use a term familiar to the ancient Nemeans, of a “demos”—a people which feels itself a people. Few want a superstate with fully integrated fiscal and monetary policy, defence policy and rights of citizenship. For all that Mr Weber and other parliamentarians may want to make the elections pan-European and quasi-presidential, voters will continue to be primarily parochial.

Nevertheless, the decade of living dangerously seems to have reshaped European politics into something a bit more cohesive, if not coherent. Europe is no longer in the business of expansion, or of integration come what may. It is in the business of protection. “A Europe which protects”, a phrase you cannot avoid in the corridors of Brussels, is increasingly heard on the campaign trail, too. Policy differences now play out within a broadly shared conviction that Europe’s citizens need, and want, defending from outside threats ranging from economic dislocation to climate change to Russia to migration. Some politicians offer integration as protection; others prefer simple co-ordination. But even parties once resolutely anti-EU, such as Austria’s hard-right FPO, now demand the EU do more, not less—at least in areas like border control and anti-terrorism.

There is also hope from an economic and development point of view. One compromise that became a straitjacket for eurozone members is the Growth and Stupidity Stability Pact, which was inserted based on a German insistence that it did not want to pay for the fiscal irresponsibility of other eurozone member states, and therefore limited the fiscal room of each country in the euro. While budgetary discipline has done wonders for Germany because of its exports to the rest of the region, the Teutonic cultural bias against fiscal deficits and inflation has hampered growth in eurozone.

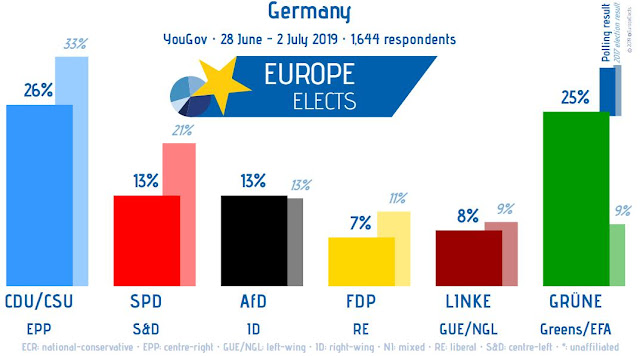

That may be about to change. The Greens have been climbing in the polls in Germany, and they are threatening to upend the control of Merkel’s CDU/CSU coalition.

The German Greens have different priorities than the current government. The Economist reports that Germany has faced difficulty in meeting carbon emission reduction targets:

Much of the frustration comes from Germany’s sluggish performance. In the past decade it has spent a fortune rejigging its energy system while barely reducing emissions. This embarrassment comes with a price tag; under EU rules Germany could be liable for penalties worth tens of billions should it fail to meet its 2030 target. The 2020 goal is already abandoned.

Two factors explain this. First is Germany’s ongoing dependence on coal, particularly lignite, the dirty brown sort. Thanks to hefty subsidies, renewables account for over 40% of electricity production. But Mrs Merkel’s sudden abandonment of nuclear power after a tsunami-induced meltdown at a Japanese reactor in 2011, and warped price signals that made gas-fired power uneconomical, meant that cheap coal has made up much of the rest. The last mine is due to be shuttered by 2038. Too late, say activists.

Secondly, since 1990 Germany has failed to bring down its emissions from transport. Some cities have banned diesel-powered cars from their centres, and carmakers are rewriting business models to avoid being overtaken by Chinese upstarts. But a future in which Germans zip around in electric cars is some way off. Nor are the incentives yet in place for the mass refurbishment of Germany’s housing stock.

The governing parties face dilemmas balancing climate protection with their traditional economic goals. The CDU wants to avoid harming industry, already smarting from high energy prices, and is wary of the powerful motorists’ lobby. The SPD fears for its industrial voter base. Many of the coal mines earmarked for closure lie in Germany’s east, where the hard-right Alternative for Germany is popular.

All this bolsters the Greens, with their crystal-clear pitch, made from the safety of opposition. The party gains from voters’ climate worries, but also from their frustration with a fractious coalition. Yet its success in soaking up votes from across the political spectrum hints at shaky foundations. It cannot remain all things to all voters. “We know our support is fragile,” says Kerstin Andreae, a Green MP. The party’s influence, however, is not.

Imagine a government in the not too distant future, with the Greens as a coalition partner, willing to loosen the fiscal budget strings on green technology initiatives. While it may not be the sort of infrastructure investment that Mario Draghi originally thought about, it would nevertheless signal an era of more relaxed fiscal restraint that could provide a boost to growth, not only in Germany, but also throughout Europe.

In addition, the news that IMF director Christine Legarde is to be named the head of the European Central Bank is also supportive of growth in the eurozone. Bloomberg summarized her views on monetary policy. Legarde’s views puts her very much in the pragmatists’ camp, and she would make a good successor to Mario Draghi:

- Outright Monetary Transactions: Legarde has voiced support for Draghi`s never used “whatever it takes” tool.

- Negative interest rates: She is in favor of negative interest rates to deal with the problem of zero lower bound.

- Quantitative Easing: She has voice support for QE.

- Fiscal support: Legarde is above all, a politician, who realizes the limits of monetary policy, and will do what she can to prod member states (especially the Germans) to support growth with fiscal measures.

Here is the clincher for the European bull case. Bloomberg reported that Warren Buffett is borrowing in euros, which may be a prelude to an acquisition in the not too distant future:

Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Inc. is selling debt in Europe. For those of us on the Buffett M&A watch, the move certainly raises an eyebrow.

Berkshire has hired banks to manage a benchmark sale of 20- and 30-year bonds in euros, as well as in pounds, Bloomberg News reported Tuesday, citing a person familiar with the matter. It would be the Omaha, Nebraska-based company’s first euro-denominated bond deal since 2017 and the first time it’s ever sold debt in pounds.

Berkshire would be joining a trend of U.S. companies, such as Deere & Co., looking to take advantage of cheaper borrowing costs for long-dated euro notes. But in the case of Berkshire, the debt sale also stirs up speculation about whether Buffett is moving closer toward making an acquisition in Europe, something he’s wanted to do for a while.

If Buffett is seeing value in Europe, does that mean he sees an ugly duckling which could turn into a swan?

Short-term outlook

The short-term outlook for Europe is also turning up. There is good news on the trade front. Even as Trump retreats from global trade, the EU is expanding to fill the void. The latest trade pact between the EU and the Mercosur countries is a signal that when America retreats, Europe is waiting in the wings to advance. Finally, European companies could gain a foothold in Latin America and get a jump on their American competitors.

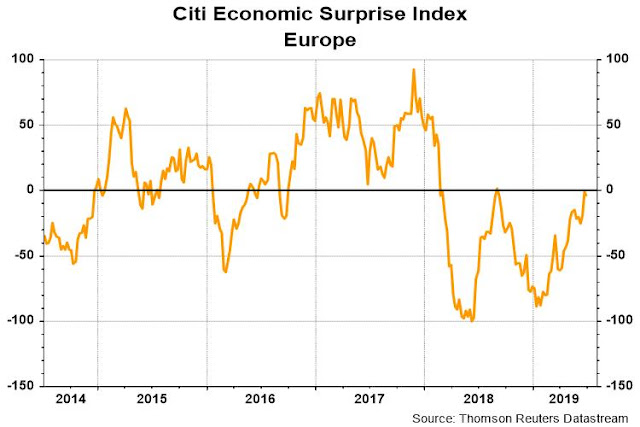

The Citigroup Europe Economic Surprise Index (ESI), which measures whether high frequency economic data is beating or missing expectations, is rising after being deeply negative for all of 2019.

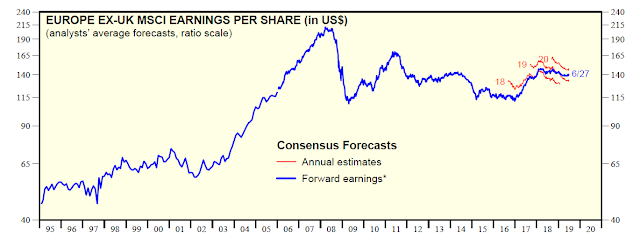

Earnings estimates for the Europe X-UK region are following a similar pattern as ESI. They appeared to have troughed and starting to rise again.

From a technical perspective, the Euro STOXX 50 has staged an upside breakout to fresh highs, and a number of other countries are also undergoing upside breakouts. Most notably, troubled peripheral country indices such as Italy and Greece (yes, that Greece) are leading the way upwards.

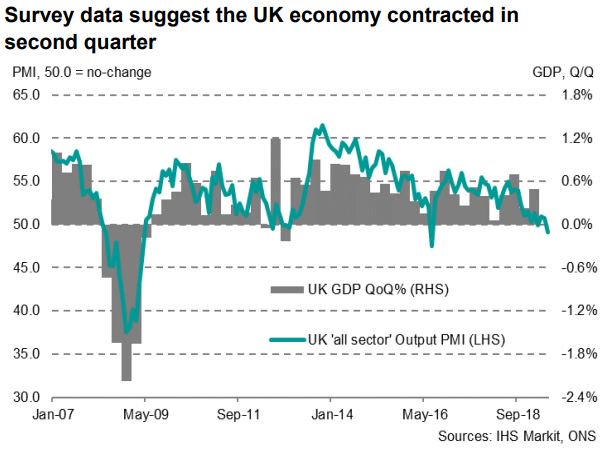

Finally, I would like to add a word about the UK, which is the only major European market that is not part of the eurozone, and probably will not be part of the EU soon. The British economy is slowing. More importantly, until the details of Brexit are resolved, I do not consider it to be an investable market because of the uncertainties involved.

In conclusion, eurozone equities appear to be poised for long-term superior performance. The short-term perspective is also supportive of the bull case. This may be a case of an ugly duckling that is on the verge of turning into a swan.

The week ahead

Looking to the week ahead, there are numerous signs that the bulls are in trouble. The first hint came last Monday, when the market staged a half-hearted attempt at a rally after the good news of a Sino-American trade truce. The market gapped up, and then spent most of the session losing ground, until a rally in the last hour recovered some ground. To be sure, prices did rise to new all-time highs later in the week, but the advance was characterized by declining volume.

The market is overbought on both a short-term and long-term basis. Short-term breadth reached an overbought condition and it is now beginning to roll over, which is interpreted by traders as a tactical sell signal.

From a longer term perspective, the Daily Sentiment Index (DSI) reached 90 last week. While DSI is not a precise trading indicator, past readings at similar levels has seen the market advance either stall out, or form a blow-off top (January 2018).

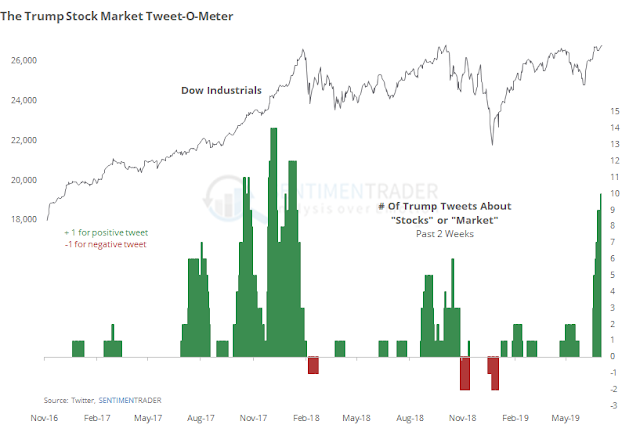

Similarly, SentimenTrader constructed a Trump Tweet-o-Meter of his stock market tweets. While the Tweet-o-Meter is also not a precise timing indicator, it does have a contrarian element when readings are high.

Another concern is the lack of leadership in this rally. The analysis of leadership by market cap shows that megacap stocks are in relative decline. Mid and small cap stocks broke down on a relative basis and they have not recovered above their breakdown levels. The only market leadership that can be seen are NASDAQ 100 stocks, whose relative price action can only be described as somewhat lethargic. Can the market really sustain an advance with such anemic leadership?

In addition, the relative performance of cyclical stocks is not feeling the love of the bulls. I interpret this to mean that market expectations for both domestic and global growth are low as we approach Q2 earnings season.

If neither Technology (NASDAQ) nor cyclical growth are the underlying drivers of higher stock prices, what about interest rates? The much stronger than expected June Jobs Report on Friday cast doubt to the thesis that the Fed would be starting a rate cut cycle. Even before the blow-out Jobs Report, the 2s10s yield curve had been flattening, indicating the bond market expected slower growth. That said, the 10s30s remain steep at a spread of 0.50%.

Tactically, stock prices appear ready to weaken. The 14-day RSI reached an overbought level and pulled back, which have been decent short-term pullback signals in the past. In addition, the latest advance has been accomplished with fewer and fewer S&P 500 new highs, which is another negative divergence. The first logical support for a pullback is the breakout level at 2950, which secondary support at about 2890.

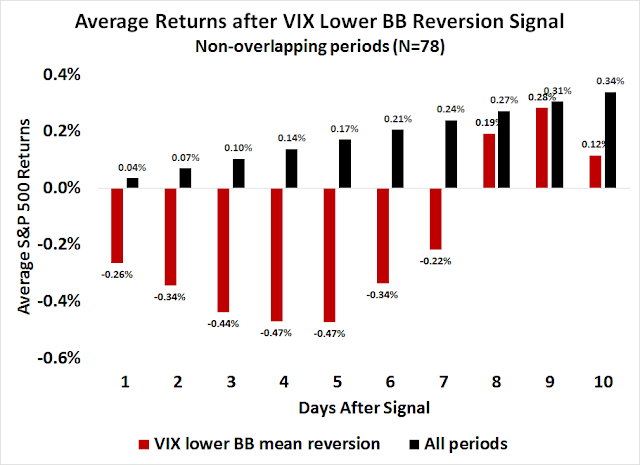

Lastly, the VIX Index fell below its lower Bollinger Band last week and mean reverted above that level on Friday. My own historical study of such signals since 1990 indicate that the market is likely to weaken over the next week.

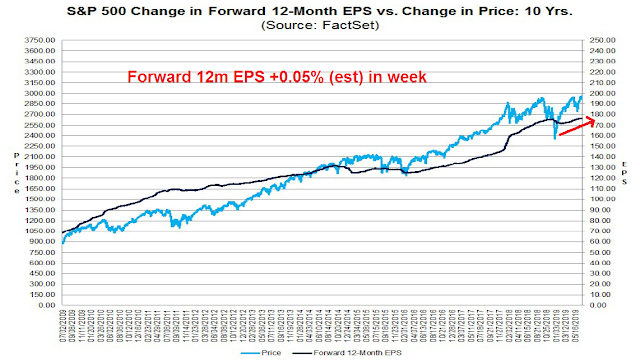

Don’t get me wrong, I am not wildly bearish. As we approach Q2 earnings season, EPS estimates are still being revised upwards, indicating positive fundamental momentum.

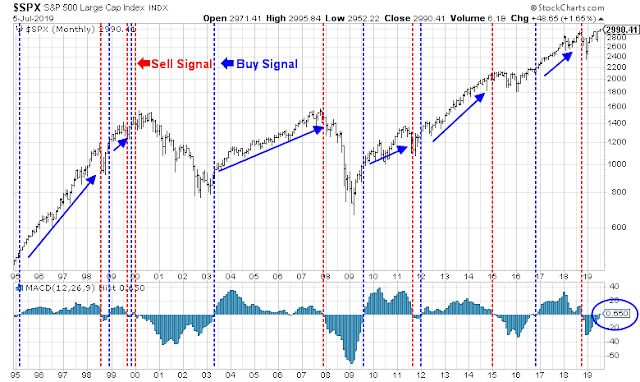

In addition, the S&P 500 has a buy signal on the monthly chart, though the signal has not been confirmed by other major indices. In the past, such signals have been sure fire indicators of a sustained advance. Should the index remain at Friday’s levels by month-end, the buy signal will be complete.

I interpret current conditions as the signals of the start of a sideways consolidation. The market is likely to be choppy in the weeks ahead as it responds to the day-to-day news from earnings season, as well as any political developments such as Robert Mueller’s scheduled Congressional testimony on July 17, and the FOMC meeting at month-end.

As the S&P 500 approaches 3000 round number resistance, recall the market`s struggle when the index first hit 1000, and 2000. Keep in mind the historical experience may or may not mean anything because of the smallness of the sample size (N=2).

My inner investor remains neutrally positioned at about the asset allocation specified by investment policy. My inner trader is short the market. He expects further weakness in the week ahead.

Disclosure: Long SPXU

An interesting twitter thread here, with a more pessimistic take on European prospects, and its banking sector in particular;

https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1147878009870983169.html

If the Eurozone slows and the ECB responds with even more QE and lower rates, the banking sector is going down the drain.

The rest of the economy will be ok though.

Cam,any European ETF that excludes banking sector? I.e. Exposure to non euro banks?

Unfortunately I am not aware of any.

I went long GREK last week. Based on your analysis, maybe adding EWI. Are there other Euro ETFs that you prefer?

GREK has been strong because of the Greek election this weekend and it is anticipated that SYRIZA will lose. Beware of a hangover effect. Greece’s troubles are not over with a change in government.

As for the others, Italy looks ok, so does France. I would focus on the entire region (FEZ) but keep in mind that this is mainly a longer term call. While the short-term outlook looks ok, anything can happen. We need those bullish catalyst of German fiscal stimulus.

If Europe is getting better, then Euro should be higher vs Dollar. Naturally SPX companies would have more revenues from Europe. So isn’t this double advantage for SPX?

The difference is valuation. According to Yardeni Research, the US trades at a forward P/E of 17.1 and Europe X-UK at 13.1.

https://www.yardeni.com/pub/mscipe.pdf

Re the chart that displays average SPX returns following reversion of VIX above the lower Bollinger Band-

Now that Day 1 has returned -0.48%, would it make sense to run an updated chart for Days 2-10 using only instances when Day 1 returns were =<0.48%?

I meant to say ‘when Day 1 returns were less than or equal to -0.48%.’

The sample size would drop dramatically, and you would be on thin ice – sort of torturing the data until it talks. Just think that the market will have its ups and downs this week, but it will have a downward bias until Friday.

OK, thanks. Knowing the sample size drops dramatically is already somewhat instructive.