Now that a QE taper announcement is more or less baked-in for this year, the next question is when the Fed will raise rates. The July FOMC minutes highlighted the point that the criteria for a taper decision is entirely different from that for a rate hike.

Several participants emphasized that an announcement of a reduction in the Committee’s pace of asset purchases should not be interpreted as the beginning of a predetermined course for raising the federal funds rate from its current level. Those participants stressed that the Committee’s assessment regarding the appropriate timing of an increase in the target range for the federal funds rate was separate from its current deliberations on asset purchases and would be subject to the higher standard, as laid out in the Committee’s outcome-based guidance on the federal funds rate.

While the rate hike decision process can be analyzed in terms of the Fed’s Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT) framework, it also depends on the Powell Fed’s newfound focus on inequality and employment. How does the Fed define full employment? In particular, a comparison of the US prime-age employment to population (EPOP) to Canada’s is a laboratory in monetary and government policies in light of the similarities in age (though not race) demographics. Canadian prime-age EPOP has been higher than the US in the last two expansion cycles and it recovered faster from the pandemic when compared to each country’s respective 2019 peaks.

All of these questions are important considerations for the analysis of Federal Reserve monetary policy.

The changing Fed framework

As I have pointed out before (see

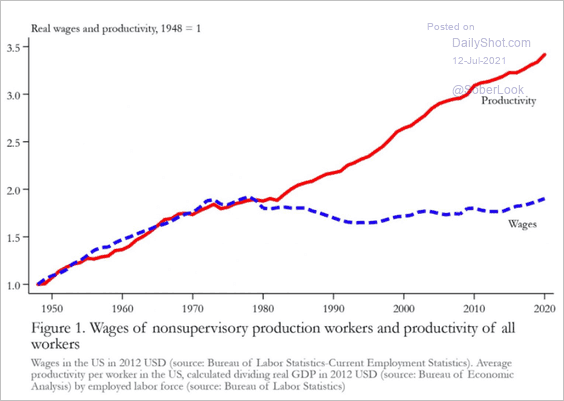

How to engineer inflation), there has been a significant shift in Fed policy in recent years. The Reagan Revolution of 1980 ushered in an era of laissez-faire economics. As a result, productivity gains have accrued to the suppliers of capital at the expense of the suppliers of labor. As productivity grew, real wage growth remained stagnant.

The suppression of wage growth was a key component of monetary policy. The Phillips Curve, which postulates a tradeoff between inflation and unemployment, was an important determinant of monetary policy. Fed policymakers targeted the unemployment rate and tightened whenever the economy boomed and unemployment neared an estimated “non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment” (NAIRU) in order to head off rising inflation and inflationary expectations. As a consequence, Fed policy exacerbated income and wealth inequality by favoring the suppliers of capital over the suppliers of labor.

The Fed discovers FAIT

The recovery out of the GFC recession was an important lesson for the Fed. The Phillips Curve flattened. As unemployment approached a NAIRU estimate, inflation remained tame. There was more slack in the labor market than thought. Inflation was nonexistent. In addition, policymakers learned through a series of “Fed Listens” community outreach meetings of the problems of rising inequality.

The solution was the Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT) framework. The Fed was willing to tolerate some overshoot of its 2% inflation target to run a hot economy in order to reach full employment. The question for investors is, “What is full employment?”

A

Bloomberg podcast with Neel Kaskari, the President of the Minneapolis Fed, was revealing. While Kaskari is one of the more dovish members of the FOMC, his comments nevertheless provided an important window of thinking around the definition of full employment.

Kashkari stated that he believes that there are still 6-8 million workers who are not in the labor force absent the COVID-19 shock. 6-8 million jobs need to return before he can declare the economy has returned to full employment. He is focusing on the labor force participation rate (LFPR) and its sister indicator EPOP as metrics of full employment.

A tight labor market

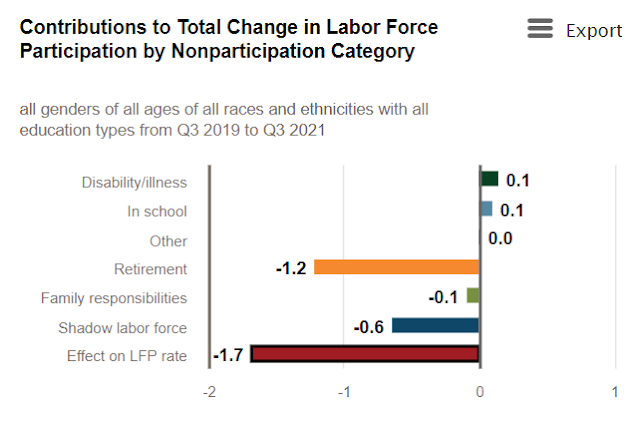

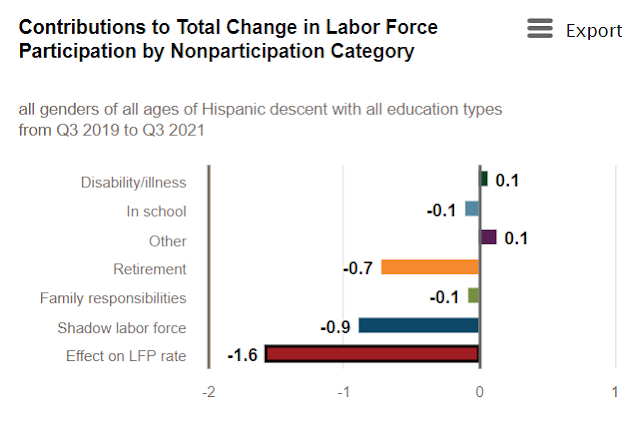

What about the widespread report of tight labor markets? While there have been many anecdotal explanations for labor shortages, the Atlanta Fed has a useful analytical tool for measuring changes to the labor force. For the two years ending Q3 2021, the decline in LFPR is mainly attributable to retirement, with a decline in the shadow labor force coming in second.

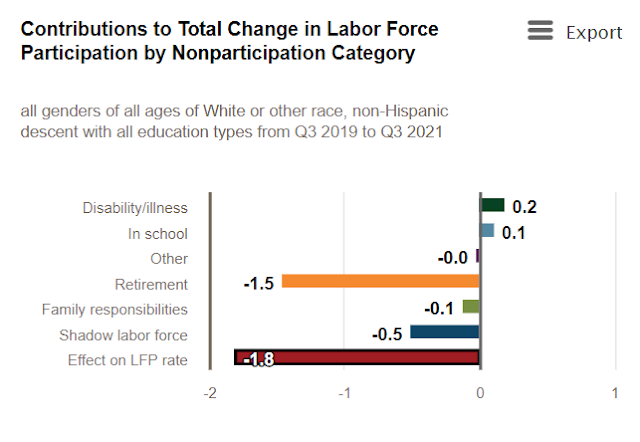

As the Fed is also focused on inequality, the analysis of changes in LFPR by race is equally revealing. The decline in white LFPR is almost entirely explained by retirement.

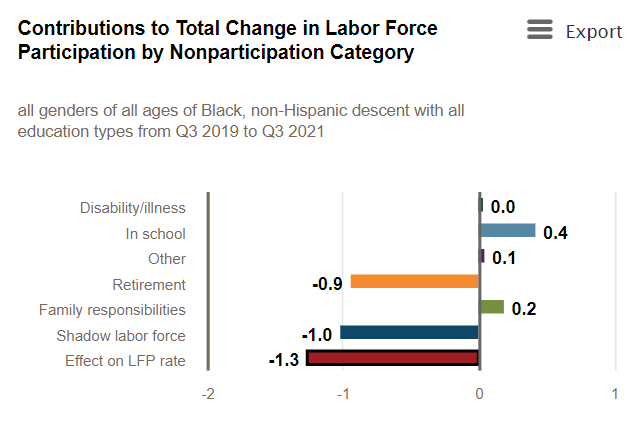

By contrast, retirement plays smaller roles in the decline in Black and Hispanic LFPR.

These results are not surprising owing to the difference in age demographics of different racial groups. White Americans have a much older age profile compared to Asian, Black, and Hispanic Americans.

Measuring wage growth

In his Bloomberg podcast, Kashkari acknowledged that wage growth has surged, but he rhetorically asked if the increase is a one-time event, which has a transitory effect on inflation, or if it’s sustained, which would drive long-term inflationary expectations.

The Atlanta Fed’s wage growth tracker shows that median hourly wage growth has surged for low-income and low-skilled workers and high-skilled wage growth remains tame. This is a preliminary sign of transitory wage and inflationary pressures which allows the Fed to stay on the sidelines a little longer. Low-skilled worker wage growth has lagged high-skilled worker wage growth since 1997. Viewed strictly through an income inequality lens, this also argues for running a hot economy for low-income workers to catch up.

The analysis of wage growth by race tells a story of labor market slack. Non-white wage growth is more volatile and it has exceeded white wage growth during strong labor markets. This also argues for a high degree of slack in the labor market.

Based on all these metrics, the labor market has a long way before it has healed. The economy is far from full employment.

Full employment and inflation

Even though Neel Kashkari is viewed as a dove who is focused on labor market dynamics and full employment, he allowed that Fed officials cannot ignore their inflation mandate in determining monetary policy.

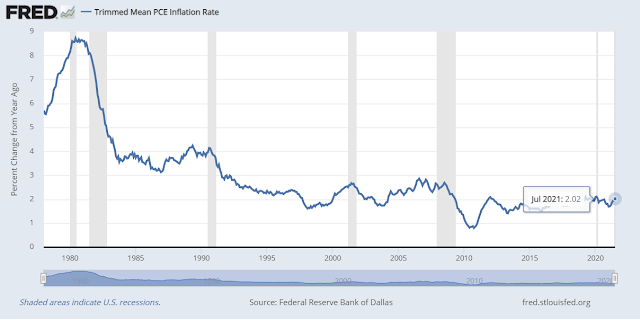

While inflation indicators have recently spiked, Kashkari is monitoring metrics like wage growth and the sources of inflation by sector. So far, inflationary pressures are attributable to temporary factors such as used car prices and airfares, which are receding after a short-term surge. Trimmed mean PCE, which is now Jerome Powell’s favorite inflation indicator, is still relatively tame.

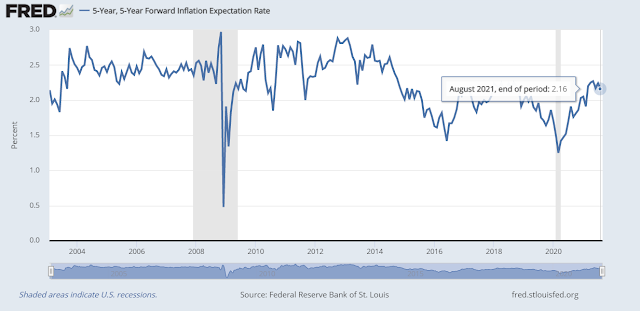

As well, 5×5 inflationary expectations are not running away, which should be comforting for policymakers.

The taper and rate hikes

Putting it all together, what does this mean for Fed policy? The

July FOMC minutes imply that a taper decision is likely in 2021, though a move during the September meeting is unlikely. Going into Jackson Hole, the BoA Global Fund Manager Survey shows that the overwhelming consensus is the Fed will signal a taper during the August-September period. In other words, the market has fully discounted a taper announcement, though the timing is probably more dovish than market expectations.

Tactically, that the exact timing of a taper announcement is unlikely this month. The Fed’s communication strategy is likely to shift towards emphasizing the difference in criteria for taper and rate hikes. This makes a hawkish surprise difficult.

As for the timing of the first rate hike, the

CME Fedwatch Tool shows that the market is expecting the first increase at the December 2022 meeting.

Frankly, it’s difficult to speculate far into the future. In a separate

Bloomberg podcast, Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan called for pulling the QE taper forward, which has the unintuitive effect of pushing a rate hike schedule further into the future.

Tapering could help take some of the pressure off the need to raise \interest rates in the future, according to the Dallas Fed president. “Adjusting these purchases sooner might actually allow us to be more patient on the Fed funds rate down the road,” he says. It’s a nice reminder that tightening monetary policy doesn’t have to be a monolithic or even linear activity.

In conclusion, investors need to be data-dependent rather than time-horizon dependent on the timing of Fed policy action. While there may be disagreement among Fed officials, the Neel Kashkari Bloomberg interview outlined many of the metrics that the Fed is monitoring, namely labor market tightness and the guideposts to full employment, and inflation expectations, as well as the interaction between the Fed’s full employment and price stability mandates.

Hi Cam – This is very interesting. You’re good at synthesizing complex subjects and it’d be great to read more thought pieces like this. Your posts on timely fundamental topics were the reasons I subscribed over 5 years ago, when I remember them being more frequent.

Hi Cam, a very nice post. A question. How does the Fed justify crafting policies based on the actual data? Isn’t that driving while looking at the rearview mirror?

I gave my head a shake after reading this and thought, “Why is this such a big worry? We are talking a quarter point rise in rates every year for the next three years according to Fed Funds Futures.”

Investment commentators need to attract readers or viewers by setting a scene of possible danger. If rates go up a quarter percent a year for three years, that is likely the tamest tightening in history and a path that has lead to strong stock markets when its happening. We are like PTSD soldiers coming back from a war (the 2020 Crash) and panic at the sound of a door slamming shut.

Other worries like the support programs ending are not a huge problem because savings rates have been incredibly high to keep spending going.

Worries about Covid Variants crashing consumer spending are countered by real time data showing people are out and about like they aren’t worried. Even public transit is back. People are learning to live with this scourge.

The Infrastructure Bill will solidify government fiscal spending going forward to not have a repeat of GOP fiscal drag under Obama after the GFC that hampered economic growth.

We have supply chain problems that are being solved and are there because corporations have been surprised by the incredible demand for their products. The cost of shipping containers has tripled because US demand is so great.

Afganistan a problem? Before the US went in and spent money, the GDP was $5 Billion. This is less than any company’s sales in the S&P 500.

China crackdown a problem? They are aiming to spread the wealth since it has become too concentrated with the hyper-wealthy. Seems to me that will increase consumer spending as the general population will have more money. Bad for certain stocks but good for the people.

2022 mid-terms with GOP coming back to clog the Dems spending a problem? The GOP is proving to be inept at stopping the pandemic in their states and they are voting against social spending that is going directly to the less well off rural folks that were GOP voters. The fringe element of the GOP party is getting so far out crazy that I wouldn’t be surprised that a shift from GOP moderates and Undecided to Dems could lead to a shocker sweep in 2022. Media folks making more that $400,000 who will be taxed will keep calling for a GOP mid-term sweep. But they are a small minority and can’t gauge the mood of the regular people.

All this to say, we have a MUCH safer road ahead in stocks than the media leads us to worry about.

In the footnotes to his speech, Powell mentions Goodhart and Pradhan (2020) and their take on inflation: “The ordinary worker’s real income has been rather stagnant over the last 30 years. We ascribe that, in our forthcoming book, to the huge positive labour supply shock that was caused by globalisation and favourable demographic effects. That enabled employers to threaten to move jobs to Asia or to more compliant migrants coming to home territory, unless workers moderated their demands; and this was a credible threat. A combination of Trump-type policies, populism, barriers to migration and now the coronavirus pandemic has now defanged that threat to workers.”

In addition to those wage increases, the current supply chain issues incentivize companies as well as governments to move supply chains “back home” – TSMC’s 10-20% price increase across their product range should give us a rough idea of what this could mean. These are in addition to prior price increases.

Powell goes on and specifically mentions the period from the 1950s to the early 1980s – he tries to sell us that the main lesson from this period has been that premature monetary tightening can be harmful. But he also mentions the 70s and that inflation expectations led to the persistently higher inflation readings even after the oil and food inflationary shocks eased. We’ll see how this plays out, but inflationary expectations as measured by T5YIFR Fred data jumped 9 basis points on Friday (Cam has Thursday’s data in his chart above)

How much credibility does this Fed have in fighting inflation? As outlined by Cam above, the majority of Fed members remain focused on the labor market (and possibly a “market reaction” as Powell committed earlier)

Powell keeps talking about used car prices while PMI reports are mentioning increasing producer input price inflation for months now.

For a specific class of asset prices the month-by-month speed of fed rate hikes may not matter so much. For long duration assets it is probably more appropriate to monitor inflation expectations, because even if the Fed will be slow to act on rising expectations (and we probably all expect that Powell – the anti-Volcker – will be very reluctant to react) – what matters in the end is that someone (may it be Powell or not) will have to act more forcefully to restore the Fed’s credibility in fighting inflation.

What are long duration assets? Thanks.

The duration of an investment is the time taken to return ones cash principal. Therefore a long duration asset takes a long time. A high dividend stock will give you your cash principal back quickly compared to a growth stock with a low dividend that is growing fast.

A long duration asset swings more widely with interest rates. So higher rates will push the value down

Thanks.

I was also reminded of recent remarks by the University of Michigan consumer confidence survey:

Consumers’ complaints about rising prices on homes, vehicles, and household durables has reached an alltime record (see the chart). Purchase rates, however, have benefitted from record increases in accumulated savings and reserve funds. A critical issue is whether consumers will find greater value in keeping a significant portion of their savings as a precautionary hedge, or spending a significant portion in an effort to avoid their inflationary erosion and to benefit from buying-in-advance of increasing market prices. The precautionary impulse will quickly fade if the “transitory” spike in inflation extended into 2022.

Back to Fed policy, the report also mentions:

Small policy steps could now have a large impact on ending inflationary psychology. A slight increase in interest rates would be no surprise to consumers as 70% expected an increase in early July, a significant shift from the start of 2021 (44%) or from last July’s survey (31%).

Powell was reluctant to take this step now, as outlined earlier he is following the script that was suggested by earlier research (Bianchi, Rottner, Melosi 2019) of “opportunistic relfation” – i.e. not reacting to initial inflationary pressures with the aim of lifting inflation expectations in the long to medium term.

The July UMich report remarks on this:

The expected year-ahead inflation rate was 4.8% in early July, up from last month’s 4.2% and May’s 4.6%. The long-term expected inflation rate provided a solid anchor, at 2.9% in July, between last month’s 2.8% and May’s 3.0%. Every instance of a comparable rise in near-term inflation expectations since 1990 was eventually countered by the maintenance of a much lower expected long-term inflation rate. While this suggests a well-anchored inflation rate, the factors that now underlie the recent surge in inflation are quite unique. A rising inflation in the months ahead may convince consumers that they underestimated its eventual rise, causing them to revise how high it will climb and how long the inflation runup will last.

In his 2021 Jackson Hole speech, Powell stressed again the importance of inflationary expectations.

The elephant in the room is technology….many people are unemployable because a machine does a better job.

It’s all a spectrum, like IQ…the machines/AI are eating the lower tail…it’s not going away. Full employment ain’t gonna happen.

When they had the industrial revolution, you know those machines doing crops and stuff (combines), so people left the farms to the cities and worked on assembly lines, which in spite of the where is the gun I can put to my head factor were better than swinging a scythe in the fields….so now the assembly lines have moved to China et al, where to now? The metaverse? I don’t think so…..call it the “dark side of productivity”, but what leads to increased productivity wins…like with evolution….so society has to change…we have to accept that some people will not have jobs….meh 10,000 years BC a one legged mastodon hunter (just trying for humor)…Ideally those not employed would be helped to find some fulfillment in life…not gonna happen ofc