As the clock ticks down on Trump’s days in the White House, and Biden election has been confirmed by the Electoral College, it’s time to ask if a Biden Administration will reset the Sino-American relationship. The key questions to ask are:

- What does each side want, and what are the sources of friction?

- What constraints is China operating under?

- What’s the likely path forward?

What does each side want?

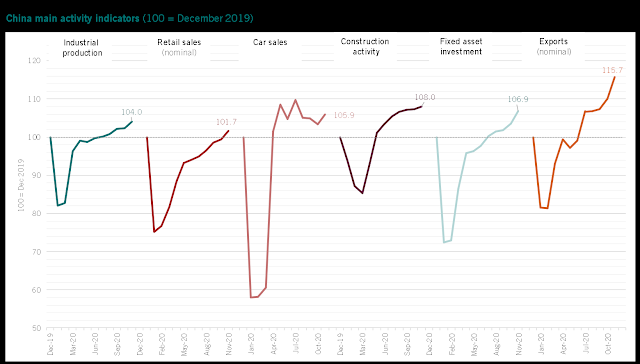

China’s unbalanced recovery

A GDP growth target that is below the underlying growth rate of the economy (as it was until 10-15 years ago, when GDP growth always exceeded the target) is consistent with a rising private-sector share of the Chinese economy. In that case private sector investment is profitable, and not surprisingly it drives much of the productive growth in the economy. But once the real growth rate of the economy slowed significantly, so that Beijing’s GDP growth target exceeded the country’s real underlying growth rate, the only way it could be met was with an increase in the state-sector share of the economy. In that case the private sector simply could not find enough productive activity to generate the politically-determined GDP growth target, and so the private-sector share of the economy necessarily had to decline.

Decoupling, by another name

Beijing’s latest solution is a “dual circulation” strategy, which amounts to maintaining global exports while developing a domestic supply chain. The Economist explains.

Enter the newest of China’s big economic policies: the “dual-circulation” strategy. At its most basic it refers to keeping China open to the world (the “great international circulation”), while reinforcing its own market (the “great domestic circulation”). If that sounds rather vague, it is: the government has not spelled out the details.

“Dual circulation” is just another term for decoupling.

That combination—the pursuit both of economic self-reliance and of greater economic leverage over foreign countries—now describes much of what China is doing. Mr Xi refers to changes “unseen in a hundred years” sweeping the global order—a way of saying that, while China is rising, America is declining and trying to stop the new power (see Chaguan). “Where linkages with the global economy create vulnerabilities, China wants to minimise them,” says Andrew Polk of Trivium China, a research firm. “Where the linkages create benefits, China wants to expand them.”

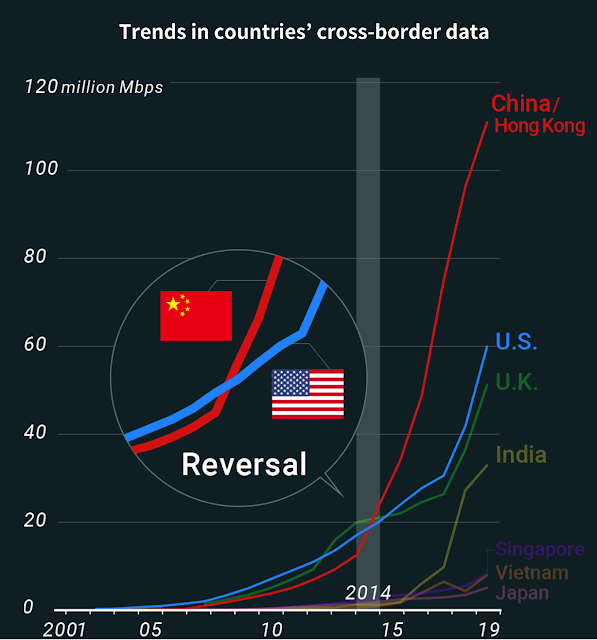

Decoupling is already a reality. Nikkei reported that a splinternet has developed, as cross-border data flow along the China/Hong Kong axis has skyrocketed while leaving the West behind.

China recently signed a free trade agreement which many interpreted as a counter-weight to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The new agreement is called Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), and it spans 15 countries and 2.2 billion people, or nearly 30% of the world’s population. Before everyone gets too excited, Michael Pettis poured cold water on the idea that RCEP will form a new parallel trade bloc.

The RCEP countries together have been running current account surpluses of more than 2% of their collective GDP, and except perhaps in the cases of Australia and New Zealand, these surpluses are based on structural savings imbalances. They are consequently very hard to eliminate without politically-difficult domestic adjustments that none of them want to accept.

This means that the RCEP can only function as a trade bloc either if some of its members are forced into running deficits (in practice only Australia and New Zealand, but they are too small to absorb more than a small fraction of the total), or if the RCEP is simply a surplus trading bloc in search of counterparts willing to run large deficits…

That leaves only the US, the UK, and Canada, and if they should take real steps to limit the deficits they are willing or able to run with RCEP, for example by limiting net capital inflows, the RCEP will fall apart as each surplus country tries to protect its all-important exports at the expense of imports and its trade partners.

China bulls believe that the strategy will ultimately compel China to open up its economy, according to The Economist.

Take the semiconductor industry. Caixin, a Chinese financial magazine, reported last month that Huawei, a tech giant, was rushing to create a “not-made-in-America” supply chain by 2022. Initially, however, that would enable it to make chips with transistors spaced 28 nanometres (billionths of a metre) apart, far less dense than the most advanced ones. The bullish case is that China, realising how long it will take to catch up in such areas, will try to boost productivity by cracking on with hitherto slow-moving reforms. Analysts with Huatai Securities, a brokerage, think that could include doing more to loosen the household-registration system known as hukou, which impedes the movement of rural labour to the country’s biggest and most productive cities.

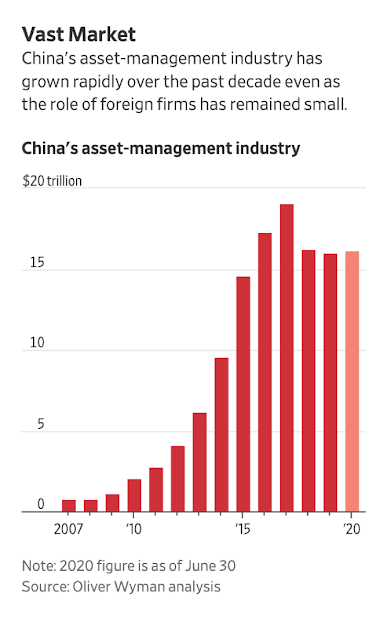

Should China open its economy to foreign companies, the opportunities are still enormous. As an example, the WSJ reported that Wall Street is salivating over the prospect of entering China’s asset management industry, which is grown to about US $18 trillion. Foreign firms only have a minuscule market share at less than 2%.

What will Biden do?

In light of these challenges and opportunities, how will a Biden White House react to China?

President-Elect Biden has not outlined the specifics of his policy on China, but we can make some educated guesses. Jeff Bader was the point person for China policy during Obama’s first term. He outlined the issues in a Brookings Institute essay facing the Biden team as it takes office.

- China’s growing power in all domains.

- The halt, and in some cases reversal, of market driven reform of the economy and greater emphasis on central control and guidance at a time when Chinese economic power abroad is growing and, in many places, disruptive.

- The return of stress on ideology, including indoctrination of officials in Marxism, tightening of space for dissent, heightened domestic surveillance enabled through technological advances, mass incarceration and “reeducation” of Uighurs in Xinjiang, and the recent crackdown in Hong Kong curtailing its autonomy and political freedoms.

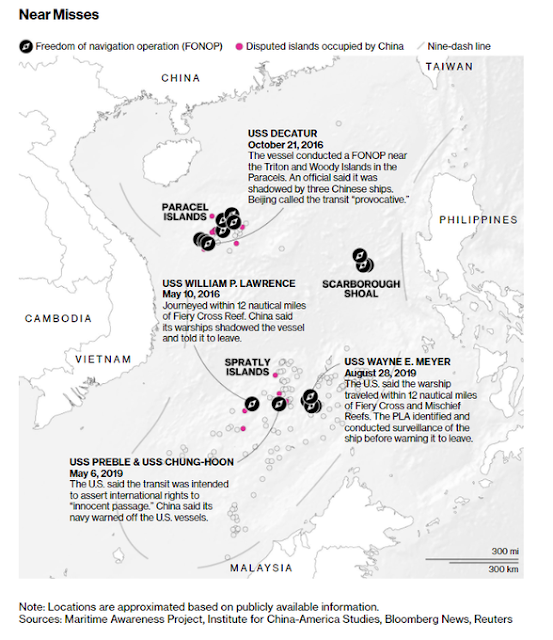

- Threats to neighbors through bullying and, in some cases, use of the PLA (People’s Liberation Army), notably the change in the status quo in the South China Sea and recent border clashes with India.

China will not be a global military power able to match the United States for the foreseeable future. America’s nuclear and ballistic missile forces, ability to project power, global system of alliances and bases, and war fighting experience are advantages that are unlikely to be eroded. China’s military poses a regional challenge but is not an instrument designed for an unprovoked attack on the United States.

China’s economic power will rise, but it will not be globally dominant.

China’s economy will surpass the United States in gross domestic product, but it will lag well behind the United States in GDP (Gross domestic product) per capita for the foreseeable future. That will mean that demands for attention to domestic needs will continue to loom large for Chinese leaders. These domestic demands will provide some restraint on ambitious overseas spending (such as for BRI) that are unpopular in China. Internationally, there is no doubt that China’s spectacular surge to global leadership in trade, investment, and infrastructure development provides the country with greater influence, but China is many years, perhaps decades, away from being a rule maker rather than a rule taker in international finance, capital markets, and currency. It lacks the foundation of rule of law, currency and capital account convertibility, an independent central bank, and deeply liquid markets that international investors seek, all of which will be necessary for it to provide an alternative to the U.S. dollar as an international currency.

From an economic perspective, China is losing the war of ideas in globally. Macro Polo compared and contrasted the rise of Japan and the rise of China. While many countries rushed to emulate Japan’s business and economic development model at the time, none have done the same with China.

Much talk has centered on China’s influence in the West. But one important area where China barely registers influence is on Western industry’s practices and management thinking. In fact, when compared to Japan, China’s influence is notably weak in the corporate realm.

The rise of “Japan Inc.” (~1950-1980) was accompanied by one of the most influential management concepts of the post-World War II era: the Toyota Production System, or commonly referred to as lean production. It wasn’t simply an idea, but an organizing principle with concrete practices that led to a transformation of the prevailing mass production model in the Western auto industry.

In contrast, the rise of “China Inc.” (~1990-2020) has seen no equivalent management philosophy or practice that has come anywhere close to the influence that Japan’s lean production has exerted.

Bader concluded that China is a competitor, but not an existential threat to American interests in the manner of the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Instead, it is seeking to be a dominant regional power and to carve out a sphere of influence in Asia.

There is no evidence suggesting that China seriously aspires to threaten the United States homeland or seek a global confrontation with the United States replicating the pattern of the U.S.-Soviet Union Cold War. Rather, we can expect to face a China that strives for economic preeminence in East and Central Asia, military security against the United States in the western Pacific, and rising but not predominant influence outside of Asia based largely on economic connections. We should not expect China to build up a network of like-minded or satellite states that pose a security threat to the United States, or to adopt the U.S. role in recent decades as the world’s policeman.

China is not an existential threat to the United States, but there is no avoiding the fact that we will be competitors and, in some respects, rivals — economically, politically, militarily, and technologically. That will require the United States to get its house in order in numerous ways that go beyond the scope of this paper, as domestic rejuvenation is the basis for successful competition. Such competition also will compel limitations on cooperation in some areas where the United States and China interacted relatively freely in the past.

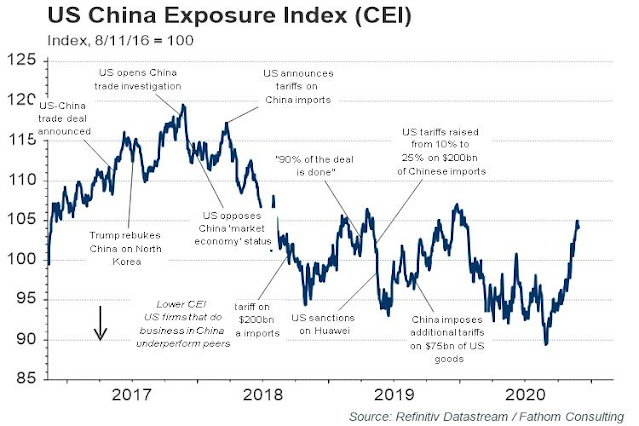

What does this mean for American policy? A consensus has developed in Washington that China represents a threat to US interests. The good old days of rapprochement are gone. The path of least resistance is a continuation of the multi-lateral containment approach last used by Obama. Biden is likely to re-enter TPP, which was a trade agreement designed to contain China’s growing influence.

As well, Bloomberg reported an increased desire to challenge China from a geopolitical perspective.

Biden looks set to maintain or even expand the number of FONOPs [freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea]. Jake Sullivan, his pick for national security adviser, last year lamented the U.S.’s inability to stop China from militarizing artificial land features in the South China Sea, and called for the U.S. to focus more on freedom of navigation.

“We should be devoting more assets and resources to ensuring and reinforcing, and holding up alongside our partners, the freedom of navigation in the South China Sea,” Sullivan told ChinaTalk, a podcast hosted by Jordan Schneider, an adjunct fellow at the Washington-based Center for a New American Security. “That puts the shoe on the other foot. China then has to stop us, which they will not do.”

The U.S. has played a key role in maintaining security in Asian waters since World War II. Yet Beijing’s military buildup, combined with moves to fortify its hold on disputed territory in the South China Sea, has raised fears that it could look to deny the U.S. military access to waters off China’s coastline. In turn, the U.S. has increasingly sought to demonstrate the right to travel through what it considers international waters and airspace.

That said, Biden will likely employ a multi-lateral approach to containment.

Biden may also try to get allies to join. A U.K. warship reportedly carried out a sail-by near the Paracel Islands in 2018, and French naval ships have patrolled in the South China Sea. A senior U.S. official said in July that the U.S. “would always like to see more like-minded countries participate” in the FONOPs program to build international consensus and pressure Beijing, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation reported.

How Biden reacts to the following key questions will also be clues to his China policy.

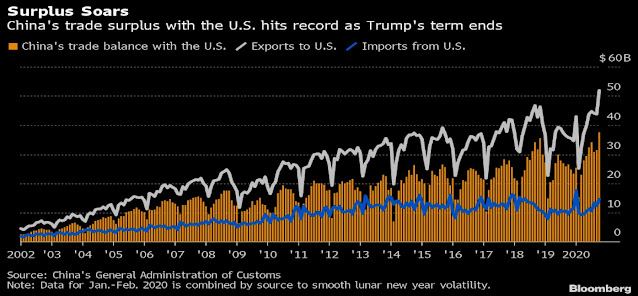

How will the new trade negotiator respond to China’s import benchmarks under the Phase One deal negotiated under Trump? Trump’s idée fixe was the trade deficit as a drain on American economic strength and jobs. Will Biden continue to focus on the trade deficit, or will he pivot to greater access to Chinese markets by American companies and intellectual property right protection?

“The document says Australia has unfairly blocked Chinese investment, spread ‘disinformation’ about China’s efforts to contain coronavirus, falsely accused Beijing of cyber-attacks, and engaged in “incessant wanton interference” in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Xinjiang.It also lambasts the Federal Government’s decision to ban Huawei from 5G networks and criticises Australia’s push against foreign interference, accusing it of ‘recklessly’ seizing the property of Chinese journalists and allowing federal MPs to issue ‘outrageous condemnation of the governing party of China’.”

Investment implications

In the short-term, none of these concerns matters to the markets. The Chinese economy is enjoying a Recovery Renaissance. The yuan is strengthening against the USD.

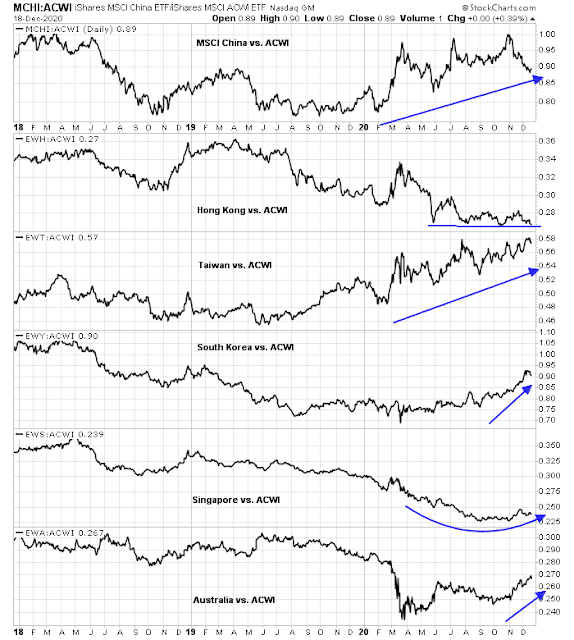

The Chinese bond market is one of the few bond markets in the world that’s offering positive real yields. This will undoubtedly attract foreign fund flows, notwithstanding the heightened credit risk as evidenced by rising defaults. The relative performance of Chinese equities to MSCI All-Country World Index (ACWI), as well as most of the markets of China’s major Asian trading partners, are all showing different constructive patterns of positive relative strength.

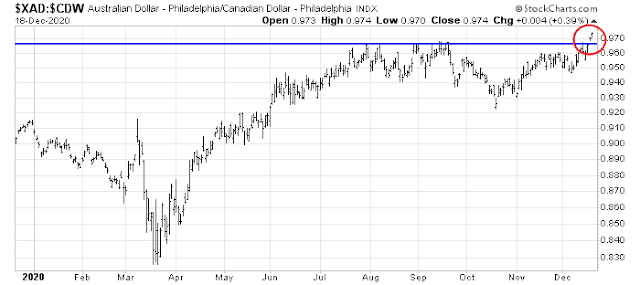

In addition, the market is shrugging off the Australia-China trade and foreign policy friction narrative. The AUDCAD exchange rate just rallied to a fresh recovery high. Both Australia and Canada are resource exporting countries. Australian exports are more levered to China, while Canadian exports are more sensitive to the US economy. Strength in the AUDCAD exchange rate is a market signal of Chinese economic strength, and falling concerns over the Australia-China relationship.

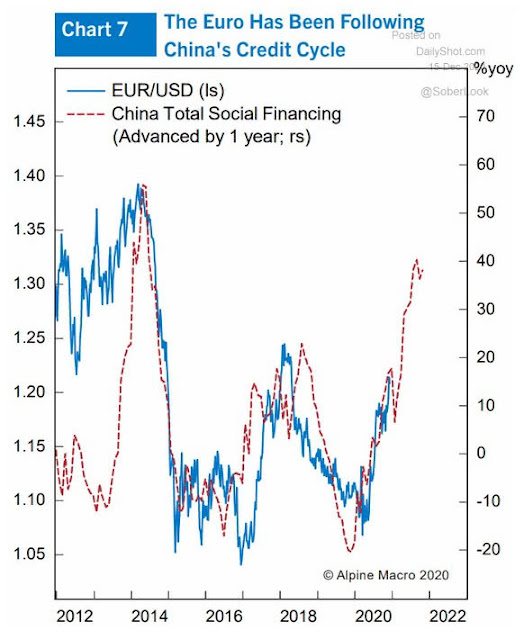

China’s yuan strength and credit-driven recovery are also good news for Europe. European manufacturing is closely linked to the health of the Chinese economy, because China depend on Europe, and Germany in particular, as a source of capital goods. This is bullish for the euro, and bearish for the greenback. As well, a falling USD should provide a boost for commodity prices and emerging markets.

From a long-term perspective, however, CNY strength will create a headache for Chinese authorities. A strengthening currency will erode export competitiveness. While the PBoC can lean against yuan strength in the short-term, regulators are likely to encourage and accommodate greater capital outflows as a medium-term solution. However, the liberalization of the capital account will raise the risk of systemic instability. But that’s a problem for tomorrow.

In conclusion, Trump’s approach to the trade dispute with China was constrained by contradictory objectives. It was impossible to focus on both the trade balance and compel China to open up its markets and respect intellectual property. Should China open its markets, foreign manufacturers would flood in and offshore jobs there, and raise the trade deficit.

Biden is likely to pivot from a belligerent to a more multi-lateral approach to dealing with China. However, there is a growing consensus in Washington from both sides of the aisle that China is a strategic competitor. However, it does not represent an existential threat to the US in the manner of the Soviet Union during the Cold War. If the Sino-American relationship is due for a reset, it will be reset to the Obama-Bush-Clinton path of containment and engagement.

In the short run, China is leading the global economy out of a recession. Its strength is putting upward pressure on its currency and drawing capital inflows into its market. This momentum is expected to continue, and China and China related investments, such as commodities and Asian markets, should perform well.

Tom Demark sees SPY topping out at 390.05, and the Nasdaq Composite topping out at 13,240 in the next half-month (in two weeks). And then he expects S&P 500 to decline by 5% to 11% in the first half of 2021.

https://www.marketwatch.com/story/stock-market-timing-expert-demark-confident-s-p-500-surges-5-in-next-2-weeks-11608225371

Thx. I address that point in tomorrow’s publication.

390 within two weeks would be awesome. Probably the ultimate pain trade.

Hoping, of course, that we don’t get that +5% move within one trading session next Monday 🙂

On the other hand, a market call worthy of a Marketwatch headline feels like a bowling pin set up.

1. How accurate are DeMark signals?

2. If they’re pretty accurate, that creates another problem – the one created when too many followers start front-running the same signal.

3. DeMark has been around long enough to know better than to use the word ‘confident’ when making market calls. I’m reminded here of Mark Hulbert’s ‘confident’ prediction of a correction last summer.

I would put more weight on Cam’s forthcoming comments re the DeMark signal than on the signal itself.

Although this is a stock trading newsletter, understandably it is unavoidable that geo politics and related articles and quotes would be mentioned. But it is deploring that the mentioned articles and quotes are so western ideology centric. If one was more neutral, then one question would be what are the US naval ships doing on the west side of the Pacific Ocean? Freedom of navigation? What freedom? Another example, a US EP-3E Aries II collided with a Chinese fighter jet 70 miles from Hainan in 2011, what was the US spy plane doing there? And the list of examples goes on . . and on. Why is it that the western ideology always paint Russia and China as the evil ones? If one starts with the wrong basis then the projected outcome would probably be wrong. Is it any wonder that most of the predictions made by Gordon Chang never come to pass

The question here isn’t who is evil, but American reaction to Beijing and the West’s perception of Chinese policies

Hi Cam,

I live in Australia so I am keenly aware of the effects of the “Trade War” China is pursuing with us.

Up until a few years ago we appeared to have a mutually beneficial and friendly relationship. However since Australia has started to stand up firmly for its interests in the areas of limiting foreign interference etc , things have turned quite nasty to the point that we are even unable to talk directly to our counterparts in China. The sorts of things we are standing up for are no more than any other reasonable country would require. China is now not a friend of Australia but only trading partner out of necessity. It now not safe for Australian business people to visit China for fear of being detained for some reason.

The main point I would like to make is that China’s behaviour in trying to bully countries through trade sanctions has now fully come out into the open. China appears to have made the calculation that it no longer needs to care about what other countries think of its bullying tactics.

As a result of this I would be surprised if “foreign manufacturers would flood in and offshore jobs there” if China wanted to open their markets up because of the much greater sovereign risk of dealing with China. I would have thought that this new, more openly belligerent, attitude towards its trading partners would make company executives think twice about setting up business there now.

Here in Canada we have the problem of the two Michaels with China

‘Engagement and containment’

It’s clear that western capitalists cannot let distractions like Uigher, Tibetan, and Mongolian cultural erasure, repression of Hong Kong, and intimidation of Taiwan interfere with their beggar-thy neighbor pursuit of profits.

Thus ‘engagement and containment’.

I am really glad to hear the Bob Eiger is being considered for US Ambassador to China. Disney (Mulan) has clearly demonstrated its moral bona fides wrt China. I’m sure he would be welcomed with open arms.

I grew up in Taiwan and went to college in US and now a US citizen. Over the years I was so amazed by what US policies were like toward China. The Overwhelming majority of research papers from think tanks, universities, and any institute were seriously off. I was always wondering why.

Here is what I think has been happening to these researchers:

1. Many of them are corrupted by Chinese money.

2. Others represent interested groups wanting to make money in China. After all America is just one fu–ing big business. Just look at FDR and Bush families’ history, and other big corps. To hell with ordinary Americans.

3. Yet more are leftists in bed ideologically with China.

It takes a thief to catch a thief. If you want effective policies toward China, you need to hire Americans with origins from Taiwan, HK, and China who understands CCP. If you want to deal with Cuba, you hire Cuban Americans. You don’t need those babbling heads always on TV screens.

Iger has always had political ambitions. He openly admitted so in his autobiography.