I wrote yesterday (see Why investors should look through trade tensions):

Calculated in economic terms, China would “lose” a trade war, but when calculated in political cost, America would lose as Trump does not have the same pain threshold as Xi.

Based on that analysis, I concluded that it was in the interests of both sides to conclude a trade deal, or at least a truce, before the pain became too great. In addition, the shallow nature of last week’s downdraft led me to believe that the market consensus was the latest trade impasse is temporary, and an agreement would be forthcoming in the near future.

I then conducted an informal and unscientific Twitter poll on the weekend, and the results astonished me. The poll was done on Saturday and Sunday, and a clear majority believes that it will take 10+ months to conclude a US-China trade deal, or it will never be done.

In view of this poll result, it is time to explore the stalemate scenario. What might happen if negotiations became drawn out, or if the trade war escalates?

Let me preface my analysis with the following: I am not trying to take sides in this dispute, nor am I trying to form an opinion on what should or shouldn’t be in any agreement. My objective is to analyze the situation, and determine the possible courses of action for each side, and determine whether they are bullish or bearish for risky assets.

China’ conditions

So far, most of what the market has heard has been the story from the American side. It was said that an agreement was close, but the Chinese marked up the text at the last minute and made wholesale changes. That’s when Trump hit the roof and set a short deadline for negotiations under the threat of increased tariffs. That’s the American side of the story, or spin.

Here is the Chinese side. Bloomberg reported that Vice Premier Liu He set out China’s conditions in an interview in Beijing after he returned from the latest round of negotiations in Washington, and a similar account appeared in China Daily.

China for the first time made clear what it wants to see from the U.S. in talks to end their trade war, laying bare the deep differences that still exist between the two sides.

In a wide-ranging interview with Chinese media after talks in Washington ended Friday, Vice Premier Liu He said that in order to reach an agreement the U.S. must remove all extra tariffs, set targets for Chinese purchases of goods in line with real demand and ensure that the text of the deal is “balanced” to ensure the “dignity” of both nations.

The conditions are:

- Removal of all US tariffs

- Realistic targets for the Chinese purchase of US goods

- A “balanced”deal to ensure mutual “dignity”

Let me try and read between the lines and explain China’s view. There has been too much distrust on the American side, and they believe the deal is unbalanced. Lightizer’s insistence on not lifting tariffs and the imposition of compliance penalties on China, but not on the US, are some examples of the lack of balance in the nature of the proposed agreement.

There are two types of negotiations, ones between roughly equal partners, and between unequal partners. First, in any negotiation, everything is up for grabs until the agreement is final. In a negotiation between equals, there are trades. You may have to give up something to get something. I interpret Liu’s remarks as a belief that the American side believes it is in a dominant position, and it is in a position to ask for concessions without offering anything in return.

As for the issue of a last minute change in text, Liu insinuated that the American side also went back on previously agreed upon conditions:

Liu’s comments, however, revealed yet another new fault line: a U.S. push for bigger Chinese purchases to level the trade imbalance than had originally been agreed.

According to Liu, Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping agreed “on a number” when they met in Argentina last December to hammer out the truce that set off months of negotiations. That “is a very serious issue and can’t be changed easily.”

So where are we, and what is the calculus for each side?

Trump’s choices

One school of thought is Trump believes he has the upper hand because of the strength of the US economy, which gives him the cushion to continue a trade dispute. Here is Bloomberg:

Donald Trump is making a high-stakes bet on his 2020 re-election with his decision to impose new tariffs on China: that the U.S. economy is strong enough to absorb an all-out trade war — and might even benefit.

Trump set out his rationale in a series of tweets Friday morning after raising tariffs to 25% on $200 billion in goods from China and threatening more. Chinese and U.S. officials held brief talks in Washington that were unproductive, according to people unfamiliar with the matter.

“Tariffs will make our Country MUCH STRONGER, not weaker,” the president predicted in a tweet. “Just sit back and watch!”

Should the president’s instinct prevail, he’ll enter next year’s election with the most powerful asset for an incumbent — a strong economy. As of now, he can boast of historically low unemployment numbers, positive economic growth and stock market highs. He’d also vindicate a more aggressive approach toward China than his predecessor Barack Obama — and by extension, former Vice President Joe Biden, whom Trump said Friday is likeliest to emerge as next year’s Democratic presidential nominee.

Obama and “the Administration of Sleepy Joe” allowed China to get away with “murder,” Trump said in another tweet.

Part of that “cushion” are the new tariffs pouring into the Treasury, which Trump has offered to use to buy American agricultural products to offset the loss of Chinese markets, which he will redistribute to starving nations around the world.

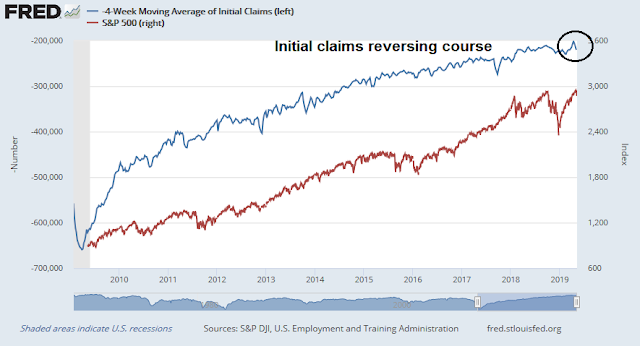

There are a couple of risks with such a course of action. First, the US economy may not be as strong as Trump thinks. While the headline Q1 GDP growth was very strong at 3.2%, final sales, which is reflective of demand after adjustments, was an anemic 1.4%. Initial jobless claims have also started to retreat from their recent record levels (inverted scale on chart), and initial claims has been highly correlated with Trump’s other favorite indicator, namely stock prices.

Rising tariffs and the expansion of the tariff list will hurt the US economy. CNBC reported that analysis from Goldman Sachs showed that the burden of rising tariffs has been borne by US consumer and businesses, not Chinese exporters. (Larry Kudlow was forced to admit on Fox that tariffs are paid by the US importer, not the Chinese exporter, via Axios):

Goldman Sachs said the cost of tariffs imposed by President Donald Trump last year against Chinese goods has fallen “entirely” on American businesses and households, with a greater impact on consumer prices than previously expected.

The bank said in a note that consumer prices are higher partly because Chinese exporters have not lowered their prices to better compete in the US market…

“One might have expected that Chinese exporters of tariff-affected goods would have to lower their prices somewhat to compete in the US market, sharing in the cost of the tariffs,” Goldman said.

“However, analysis at the extremely detailed item level in the two new studies shows no decline in the prices (exclusive of tariffs) of imported goods from China that faced tariffs.”

Bloomberg reported that Trump’s plan to cushion the agricultural sector by buying their product and redistributing it to poor countries faces a number of historical hurdles. Jimmy Carter banned grain exports to the Soviet Union, and tried to support farmers with purchases. That program didn’t work very well.

In the 1980s, crops expanded just as the export ban caused Soviet Union countries to start buying grain elsewhere. At the time, growers could deliver supplies to the Commodity Credit Corporation below certain loan rates.

It wasn’t until 1985 that the government cut that rate and stockpiles started to fall, said Pat Westhoff, director of the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute of the University of Missouri in Columbia. One of the worst droughts in history hit America in 1988, solving the overhang.

The purchases aren’t a “very effective” way to deal with overhang, “and that’s what the government eventually realized,” said Arlan Suderman, chief commodities economist at brokerage INTL FCStone Inc. “It does help support cash prices, but it limits rallies in the market because the market knows if it rallies too much, there are all those bushels still in the bin that will come out.”

The aid program also had problems. It was also the wrong kind of farm product for poor countries:

Aid programs are also too small. The U.S. government’s Food for Peace program usually buys and ships about $1.5 billion worth of goods a year to other countries. On top of that, the nations in need are usually seeking food-grade commodities, such as rice and wheat, said Joseph Glauber, former chief economist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The vast majority of U.S. corn and soy production is for use in animal feed or biofuel.

Many poor countries may also not have the facilities needed to process soybeans, which can also yield cooking oil. Some countries may also be opposed to large amounts of aid because it could hurt their farmers.

“Bangladesh does not want raw U.S. soybeans — they want wheat, or wheat flour, milk powder and such,” Basse said.

In addition, such an initiative amounts to dumping, and would be subject to WTO complaints.

Trump’s move could also generate disputes in the World Trade Organization as the measures can be seen as market distorting. The aid could send prices lower, hurting countries like Brazil and Argentina, which are also major corn and soybean exporters.

“You can’t just dump grain at concessional prices,” Glauber said. “That would constitute an export subsidy. That is something the WTO members agreed not to do.”

If Trump’s calculus is based on a strong US economy, it could turn out to be an enormous policy mistake which he will not realize until Q3 or Q4. By then, it will be too late to avoid a major slowdown in 2020 ahead of the election.

Chinese retaliation

In response to the US raising the tariff rate from 10% to 25% on an existing list $200b of imports, China announced a retaliatory measure of up to 25% on a measly $60b of US agricultural exports.

Is that the only Chinese response? What else can China do?

A well-reasoned analysis by Brad Setser came to the conclusion that currency depreciation is the most logical asymmetric response, but it will be strictly China’s choice.

One view, more or less, is that China has no need to upset the apple cart. The yuan’s recent stability hasn’t required heavy intervention (at least so long as the financial account remains controlled) or forced China to raise interest rates, and China has shown that it can stabilize its domestic economy by relaxing lending curbs and a more expansionary fiscal policy. Letting the yuan move too quickly could upset the restoration of domestic confidence in China’s economic management, and, well, force China to dip into its reserves to keep any move limited…

I suspect that China has more than enough firepower to maintain the yuan in its current band if it wants to even with U.S. tariff escalation. The tariffs—plus the Iranian and Venezuelan oil sanctions—might be enough to push China’s current account into an external deficit (China is the world’s largest oil importer, so the price of oil matters for the overall balance as much as U.S. tariffs). But if China signaled that the yuan would remain stable, portfolio inflows would likely continue—and a modest deficit need not put any real strain on China’s reserves (especially if Xi insists on a bit more discipline in Belt and Road lending to avoid new debt traps).

The other view is that China has shown that it is firmly in control of its exchange rate and balance of payments, and thus it is in a position to let its currency weaken without putting its own financial stability at risk. Controlled depreciations are hard—the market (even a controlled market like the market for the yuan) obviously has an incentive to front run any predictable move (as China learned in 15 and 16). But I suspect China could pull that off —it would just need to signal at some point that once the yuan had reset down, China would resist further depreciation. The goal, in effect, would be to reset the yuan’s trading range around a new post U.S. tariff band, not to move directly to a true free float.

That would let Chinese firms (who have already started to complain) cut their dollar prices (offsetting some of the impact of the tariff) without reducing their yuan revenues, and help China make up for lost exports to the United States with additional exports to the rest of the world…

Obviously, a controlled depreciation would be highly bearish, as it raises the possibility of a currency war, especially in Asia.

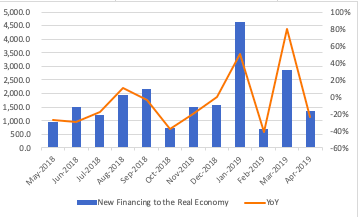

Another option is to do nothing, other than the token tariff retaliation to save face. The fiscal drag of the new US tariffs amounts to a tax increase, and the US economy will slow. Trump’s support in the farm states will erode. China can engage in further stimulus of its economy, though that is not their preferred course of action. China’s Total Social Financing retreated in April, but levels are not out of line with debt growth seen in Q1.

The political decision

So what now? How long can the trade dispute last, and what kind of damage will it do to the economic growth outlook for China, US, and the world?

It ultimately comes down to a political decision. Brad Setser also made an astute observation in the course of his analysis:

At some point Trump will have to decide whether he wants to run for re-election as the “tariff” man who disrupted world trade, or as the defender of a reformed status quo (after a great deal, that inevitably would involve a lot of messy compromises that don’t change many Chinese trade practices).

Tariff Man would drag out the dispute, and frame China as the boogeyman in the 2020 election. A recent NY Times article hypothesized that was precisely Trump’s 2020 re-election strategy. Run as Tariff Man, and vilify the Democrats, and in particular Joe Biden and the Obama administration for being soft on China. That decision will cause a lot of pain, for both Trump politically and for the markets.

On the other hand, a conciliatory Trump who initially appears tough on China but makes a deal with only minor concessions, in the manner of the KORUS and NAFTA negotiations, will be bullish. This will be in keeping with his Art of the Deal persona, the person who can make a great deal after staring down the Chinese.

I have no idea how this will turn out. My rational brain tells me that the logical outcome is for both sides to come to an agreement quickly before real damage is done. But either the political dimension, or a miscalculation of the political calculus could alter that path.

There are a number of indicators that I would monitor. In the US, I would watch initial jobless claims for signs of job market deterioration, NFIB small business confidence for signs of flagging small business confidence, as small business owners form the bulk of the Republicans’ support, the yield curve, and the stock market. A flattening yield curve would be a sign that the bond market expects slowing growth,

As for China, I would watch the CNYUSD exchange rate. Can it rise to 7 or beyond? In addition, the relative performance of Chinese property developers. Continued outperformance by this sector is a sign of stimulus and plentiful liquidity, and cratering real estate stocks would be a sign of rising stress in the Chinese economy.

Watch these indicator to see how the pressure on each side evolves, and you will know the level of urgency each has to go back to the negotiation table for a deal.

My takeaway is that Mr Hui is still bullish. I will act accordingly.

Agreed, if this continues it could break businesses and their relationships globally to a point that it would take a long time to recover.

If deals are to be made, then they need to plan how both sides can look good doing it.

“If the result is a trade war, treat it like other wars—fight to win.” Andy Grove ~2010-2011

Andy Grove, Intel Corps brilliant co-founder and CEO (now deceased) penned a couple of warning pieces years ago that have been largely ignored. His main point was “The U.S. economy is being hollowed out industry by industry.” Here’s one of his pieces:

“Recently an acquaintance at the next table in a Palo Alto (Calif.) restaurant introduced me to his companions, three young venture capitalists from China. They explained, with visible excitement, that they were touring promising companies in Silicon Valley. I’ve lived in the Valley a long time, and usually when I see how the region has become such a draw for global investments, I feel a little proud.

Not this time. I left the restaurant unsettled. Something did not add up. Bay Area unemployment is even higher than the 9.7 percent national average. Clearly, the great Silicon Valley innovation machine hasn’t been creating many jobs of late—unless you’re counting Asia, where American tech companies have been adding jobs like mad for years.

The underlying problem isn’t simply lower Asian costs. It’s our own misplaced faith in the power of startups to create U.S. jobs. Americans love the idea of the guys in the garage inventing something that changes the world. New York Times columnist Thomas L. Friedman recently encapsulated this view in a piece called “Start-Ups, Not Bailouts.” His argument: Let tired old companies that do commodity manufacturing die if they have to. If Washington really wants to create jobs, he wrote, it should back startups.

Friedman is wrong. Startups are a wonderful thing, but they cannot by themselves increase tech employment. Equally important is what comes after that mythical moment of creation in the garage, as technology goes from prototype to mass production. This is the phase where companies scale up. They work out design details, figure out how to make things affordably, build factories, and hire people by the thousands. Scaling is hard work but necessary to make innovation matter.

The scaling process is no longer happening in the U.S. And as long as that’s the case, plowing capital into young companies that build their factories elsewhere will continue to yield a bad return in terms of American jobs.

What Went Wrong?

Scaling used to work well in Silicon Valley. Entrepreneurs came up with an invention. Investors gave them money to build their business. If the founders and their investors were lucky, the company grew and had an initial public offering, which brought in money that financed further growth.

I am fortunate to have lived through one such example. In 1968 two well-known technologists and their investor friends anted up $3 million to start Intel (INTC), making memory chips for the computer industry. From the beginning we had to figure out how to make our chips in volume. We had to build factories, hire, train, and retain employees, establish relationships with suppliers, and sort out a million other things before Intel could become a billion-dollar company. Three years later the company went public and grew to be one of the biggest technology companies in the world. By 1980, 10 years after our IPO, about 13,000 people worked for Intel in the U.S.

Not far from Intel’s headquarters in Santa Clara, Calif., other companies developed. Tandem Computers went through a similar process, then Sun Microsystems, Cisco (CSCO), Netscape, and on and on. Some companies died along the way or were absorbed by others, but each survivor added to the complex technological ecosystem that came to be called Silicon Valley.

As time passed, wages and health-care costs rose in the U.S. China opened up. American companies discovered that they could have their manufacturing and even their engineering done more cheaply overseas. When they did so, margins improved. Management was happy, and so were stockholders. Growth continued, even more profitably. But the job machine began sputtering.

The 10X Factor

Today, manufacturing employment in the U.S. computer industry is about 166,000, lower than it was before the first PC, the MITS Altair 2800, was assembled in 1975 (figure-B). Meanwhile, a very effective computer manufacturing industry has emerged in Asia, employing about 1.5 million workers—factory employees, engineers, and managers. The largest of these companies is Hon Hai Precision Industry, also known as Foxconn. The company has grown at an astounding rate, first in Taiwan and later in China. Its revenues last year were $62 billion, larger than Apple (AAPL), Microsoft (MSFT), Dell (DELL), or Intel. Foxconn employs over 800,000 people, more than the combined worldwide head count of Apple, Dell, Microsoft, Hewlett-Packard (HPQ), Intel, and Sony (SNE) (figure-C).

Until a recent spate of suicides at Foxconn’s giant factory complex in Shenzhen, China, few Americans had heard of the company. But most know the products it makes: computers for Dell and HP, Nokia (NOK) cell phones, Microsoft Xbox 360 consoles, Intel motherboards, and countless other familiar gadgets. Some 250,000 Foxconn employees in southern China produce Apple’s products. Apple, meanwhile, has about 25,000 employees in the U.S. That means for every Apple worker in the U.S. there are 10 people in China working on iMacs, iPods, and iPhones. The same roughly 10-to-1 relationship holds for Dell, disk-drive maker Seagate Technology (STX), and other U.S. tech companies.

You could say, as many do, that shipping jobs overseas is no big deal because the high-value work—and much of the profits—remain in the U.S. That may well be so. But what kind of a society are we going to have if it consists of highly paid people doing high-value-added work—and masses of unemployed?

Since the early days of Silicon Valley, the money invested in companies has increased dramatically, only to produce fewer jobs. Simply put, the U.S. has become wildly inefficient at creating American tech jobs. We may be less aware of this growing inefficiency, however, because our history of creating jobs over the past few decades has been spectacular—masking our greater and greater spending to create each position. Should we wait and not act on the basis of early indicators? I think that would be a tragic mistake, because the only chance we have to reverse the deterioration is if we act early and decisively.

Already the decline has been marked. It may be measured by way of a simple calculation—an estimate of the employment cost-effectiveness of a company. First, take the initial investment plus the investment during a company’s IPO. Then divide that by the number of employees working in that company 10 years later. For Intel this worked out to be about $650 per job—$3,600 adjusted for inflation. National Semiconductor (NSM), another chip company, was even more efficient at $2,000 per job. Making the same calculations for a number of Silicon Valley companies shows that the cost of creating U.S. jobs grew from a few thousand dollars per position in the early years to a hundred thousand dollars today (figure-A). The obvious reason: Companies simply hire fewer employees as more work is done by outside contractors, usually in Asia.

The job machine breakdown isn’t just in computers. Consider alternative energy, an emerging industry where there’s plenty of innovation. Photovoltaics, for example, are a U.S. invention. Their use in home energy applications was also pioneered by the U.S. Last year, I decided to do my bit for energy conservation and set out to equip my house with solar power. My wife and I talked with four local solar firms. As part of our due diligence, I checked where they get their photovoltaic panels—the key part of the system. All the panels they use come from China. A Silicon Valley company sells equipment used to manufacture photo-active films. They ship close to 10 times more machines to China than to manufacturers in the U.S., and this gap is growing (figure-D). Not surprisingly, U.S. employment in the making of photovoltaic films and panels is perhaps 10,000—just a few percent of estimated worldwide employment.

There’s more at stake than exported jobs. With some technologies, both scaling and innovation take place overseas.

Such is the case with advanced batteries. It has taken years and many false starts, but finally we are about to witness mass-produced electric cars and trucks. They all rely on lithium-ion batteries. What microprocessors are to computing, batteries are to electric vehicles. Unlike with microprocessors, the U.S. share of lithium-ion battery production is tiny (figure-E).

That’s a problem. A new industry needs an effective ecosystem in which technology knowhow accumulates, experience builds on experience, and close relationships develop between supplier and customer. The U.S. lost its lead in batteries 30 years ago when it stopped making consumer electronics devices. Whoever made batteries then gained the exposure and relationships needed to learn to supply batteries for the more demanding laptop PC market, and after that, for the even more demanding automobile market. U.S. companies did not participate in the first phase and consequently were not in the running for all that followed. I doubt they will ever catch up.

The Key to Job Creation

Scaling isn’t easy. The investments required are much higher than in the invention phase. And funds need to be committed early, when not much is known about the potential market. Another example from Intel: The investment to build a silicon manufacturing plant in the ’70s was a few million dollars. By the early ’90s the cost of the factories that would be able to produce the new Pentium chips in volume rose to several billion dollars. The decision to build these plants needed to be made years before we knew whether the Pentium chip would work or whether the market would be interested in it.

Lessons we learned from previous missteps helped us. Some years earlier, when Intel’s business consisted of making memory chips, we hesitated to add manufacturing capacity, not being all that sure about the market demand in years to come. Our Japanese competitors didn’t hesitate: They built the plants. When the demand for memory chips exploded, the Japanese roared into the U.S. market and Intel began its descent as a memory chip supplier. Despite being steeled by that experience, I still remember how afraid I was as I asked the Intel directors for authorization to spend billions of dollars for factories to produce a product that did not exist at the time for a market we could not size. Fortunately, they gave their O.K. even as they gulped. The bet paid off.

My point isn’t that Intel was brilliant. The company was founded at a time when it was easier to scale domestically. For one thing, China wasn’t yet open for business. More importantly, the U.S. had not yet forgotten that scaling was crucial to its economic future.

How could the U.S. have forgotten? I believe the answer has to do with a general undervaluing of manufacturing—the idea that as long as “knowledge work” stays in the U.S., it doesn’t matter what happens to factory jobs. It’s not just newspaper commentators who spread this idea. Consider this passage by Princeton University economist Alan S. Blinder: “The TV manufacturing industry really started here, and at one point employed many workers. But as TV sets became ‘just a commodity,’ their production moved offshore to locations with much lower wages. And nowadays the number of television sets manufactured in the U.S. is zero. A failure? No, a success.”

I disagree. Not only did we lose an untold number of jobs, we broke the chain of experience that is so important in technological evolution. As happened with batteries, abandoning today’s “commodity” manufacturing can lock you out of tomorrow’s emerging industry.

Wanted: Job-Centric Economics

Our fundamental economic beliefs, which we have elevated from a conviction based on observation to an unquestioned truism, is that the free market is the best of all economic systems—the freer the better. Our generation has seen the decisive victory of free-market principles over planned economies. So we stick with this belief, largely oblivious to emerging evidence that while free markets beat planned economies, there may be room for a modification that is even better.

Such evidence stares at us from the performance of several Asian countries in the past few decades. These countries seem to understand that job creation must be the No. 1 objective of state economic policy. The government plays a strategic role in setting the priorities and arraying the forces and organization necessary to achieve this goal. The rapid development of the Asian economies provides numerous illustrations. In a thorough study of the industrial development of East Asia, Robert Wade of the London School of Economics found that these economies turned in precedent-shattering economic performances over the ’70s and ’80s in large part because of the effective involvement of the government in targeting the growth of manufacturing industries.

Consider the “Golden Projects,” a series of digital initiatives driven by the Chinese government in the late 1980s and 1990s. Beijing was convinced of the importance of electronic networks—used for transactions, communications, and coordination—in enabling job creation, particularly in the less developed parts of the country. Consequently, the Golden Projects enjoyed priority funding. In time they contributed to the rapid development of China’s information infrastructure and the country’s economic growth.

How do we turn such Asian experience into intelligent action here and now? Long term, we need a job-centric economic theory—and job-centric political leadership—to guide our plans and actions. In the meantime, consider some basic thoughts from a onetime factory guy.

Silicon Valley is a community with a strong tradition of engineering, and engineers are a peculiar breed. They are eager to solve whatever problems they encounter. If profit margins are the problem, we go to work on margins, with exquisite focus. Each company, ruggedly individualistic, does its best to expand efficiently and improve its own profitability. However, our pursuit of our individual businesses, which often involves transferring manufacturing and a great deal of engineering out of the country, has hindered our ability to bring innovations to scale at home. Without scaling, we don’t just lose jobs—we lose our hold on new technologies. Losing the ability to scale will ultimately damage our capacity to innovate.

The story comes to mind of an engineer who was to be executed by guillotine. The guillotine was stuck, and custom required that if the blade didn’t drop, the condemned man was set free. Before this could happen, the engineer pointed with excitement to a rusty pulley, and told the executioner to apply some oil there. Off went his head.

We got to our current state as a consequence of many of us taking actions focused on our own companies’ next milestones. An example: Five years ago a friend joined a large VC firm as a partner. His responsibility was to make sure that all the startups they funded had a “China strategy,” meaning a plan to move what jobs they could to China. He was going around with an oil can, applying drops to the guillotine in case it was stuck. We should put away our oil cans. VCs should have a partner in charge of every startup’s “U.S. strategy.”

The first task is to rebuild our industrial commons. We should develop a system of financial incentives: Levy an extra tax on the product of offshored labor. If the result is a trade war, treat it like other wars—fight to win. Keep that money separate. Deposit it in the coffers of what we might call the Scaling Bank of the U.S. and make these sums available to companies that will scale their American operations. Such a system would be a daily reminder that while pursuing our company goals, all of us in business have a responsibility to maintain the industrial base on which we depend and the society whose adaptability—and stability—we may have taken for granted.

I fled Hungary as a young man in 1956 to come to the U.S. Growing up in the Soviet bloc, I witnessed first-hand the perils of both government overreach and a stratified population. Most Americans probably aren’t aware that there was a time in this country when tanks and cavalry were massed on Pennsylvania Avenue to chase away the unemployed. It was 1932; thousands of jobless veterans were demonstrating outside the White House. Soldiers with fixed bayonets and live ammunition moved in on them, and herded them away from the White House. In America! Unemployment is corrosive. If what I’m suggesting sounds protectionist, so be it.

Every day, that Palo Alto restaurant where I met the Chinese venture capitalists is full of technology executives and entrepreneurs. Many of them are my friends. I understand the technological challenges they face, along with the financial pressure they’re under from directors and shareholders. Can we expect them to take on yet another assignment, to work on behalf of a loosely defined community of companies, employees, and employees yet to be hired? To do so is undoubtedly naïve. Yet the imperative for change is real and the choice is simple. If we want to remain a leading economy, we change on our own, or change will continue to be forced upon us.”

Does Moore’s law apply to robotics? I keep expecting the manufacturing to come back to the US when the cost of robotic assembly is such that the cost of shipping from Asia negates the benefit of manufacturing in China. This won’t create a bucketload of jobs, and the robot assembly may even be an asian company. Still it seems to be the way of things, jobs get eaten up by technology. 100 years ago, loss of rural jobs because of changes in farming meant that people moved to cities. Now where will the people in cities move to? Smart machines will just keep getting smarter, and cheaper, the only question is how fast.

‘cost of robotic assembly”

I quote you. The robots may be designed in Asia, and assembled in USA.

Ever considered this idea?

The more prolonged this ugly retreat from a deal is, the more the USA and Trump will be hurt. A strong dictatorship can withstand a protracted downturn. IF this hurts the economy and therefore many US citizens, the Dems will likely do better in the 2020 election. Surely they will sieze on this with 2 fists. Who blinks first? Trump will bluster, prevaricate and threaten. Xi will act more circumspectly. The stock market will give up much of its post December gains as LT interest rates fall–as they already have! 2% on the 10 year and serious inversion between the 2 year and the 10 year? Trump will try to brow beat the Fed into lowering ST rates down 1 full%.

It appears you are labeling the US response as spin and the Chinese response as fact am I reading that correctly? Secondly, if the deal included China changing their laws as it relates to theft of U.S. intellectual property and trade secrets; forced technology transfers; competition policy; access to financial services; and currency manipulation do you not feel that would make the deal much more substantial than your current expectations as you lay them out? Aren’t these the areas the US reporting has said caused problems with the deal last week when China walked away from including these as they had indicated they would do previously?

No, it is all spin. Our job as investors is to look at the situation from both sides, read the spin, and make judgments as to how things will turn out.

You have to understand the constraints and pressures that each side has on their actions. As an example, China will not change their system of governance, regardless of the justifications. It would be like a European demand during a US-EU trade negotiation that the US scrape its judicial system and replace it with one based the Napoleonic code, where an investing magistrate investigates offenses. Not going to happen.

In that case, you have to think about what is possible, and what the investment implications are under each outcome. Otherwise this becomes a financial Gulf of Tonkin incident and you go to all-out war.

Thanks for keeping it real Cam and seeing it from both sides to help us become more informed investors.

Cam-

Nice job managing your trades – you have the ability to sit back and assess outcomes when prices are in a tailspin.

Something I’ve been meaning to ask -why do you choose to trade with leveraged funds?

I trade my positions in a tax deferred account that does not allow leverage, sort of like an IRA. The leveraged ETFs allow me the flexibility to raise my risk profile.

The same may not be appropriate for you.

Right. I’ve run into the same problem with my retirement accounts, which only allow trading of mutual funds. I’m basically constrained to trading end of day. One way around it has been to use a Rydex leveraged fund, which offers an additional trading window about an hour into the trading session.