As new data has crosses my desk, I thought I would write a follow-up to my bullish demographic analysis published two weeks ago (see A different kind of America First). To recap, I observed that America is about to enter another echo demographic boom as the Millennial generation enters its prime earnings years.

A study by San Francisco Fed researchers pointed out that this should raise demand for equities from Millennials. This is especially important as the Baby Boomers reduce their equity holdings as they retire.

I then postulated that rising savings from Millennial should usher in another golden age in US equities.

This is the part where history doesn’t repeat itself, but rhymes.

A generation of slackers?

I had some pushback from readers to the effect that the new generation is a bunch of slackers living in their parents’ basement. But please be reminded that Baby Boomers in the youth popularized the practice of smoking pot, and once believed in “free love”. They eventually grew up, got jobs, and became responsible citizens.

A recent study by FINRA and the CFA Institute found that the approach that the Millennial generation has adopted to their personal finances are not very different from older cohorts. The study was based on eight focus groups and a 2018 online survey of nearly 3,000 Millennials, Baby Boomers, and Gen Xers. This is an important issue for the financial services industry. Forbes reported that Millennals are poised to inherit $30 trillion over the next 30 years.

When it comes to financial goals, the assumed overconfidence and ambition of millennials should translate into expectations of early retirement. But the data does not bear this out: Only 3% of millennials with taxable retirement accounts anticipate retiring before age 50, and a sizeable proportion of millennials don’t expect to retire at all. Moreover, the goals of non-investing millennials are exceptionally modest, with 40% of this group saying that their top goal is simply not living paycheck to paycheck. The goals of millennials with taxable accounts line up fairly well with those of Gen Xers and baby boomers who also have such accounts.

Despite their greater comfort with technology, Millennails are not embracing robo-advisors.

Indeed, notwithstanding their presumed tech savvy, millennials are not especially well informed or curious about robo-advisors. Of those surveyed, 37% had never heard of robo-advisors, and only 16% said they were very or extremely interested in them. Moreover, when working with a financial professional, more than half of the millennials studied said they’d prefer to do so face to face. They were similarly unimpressed with cryptocurrencies.

Their trust in Wall Street is not especially high.

So what about trust? Millennials have had to navigate the most difficult economic landscape of any generation since the Great Depression. The financial crisis has defined their world and shaped their expectations. Surely advisers can expect to have a more difficult time convincing them to take a chance and entrust them with their money, right? Apparently not. Contrary to popular wisdom, the difficult economic times have not made millennials overly skeptical of finance professionals or the finance industry. According to the study, 41% of millennials with retirement or taxable accounts work with an adviser and 72% of these are either very or extremely satisfied with them. Finally, only 15% of those millennials not using an investment professional said it was due to a lack of trust.

In that respect, demographics does look like destiny.

How history only rhymes

On the other hand, the Millennial cohort is maturity in an economic environment that is less friendly than the one experienced by Baby Boomers. The competitive environment is more challenging, and they are less likely to out-earn their parents than the Baby Boomers.

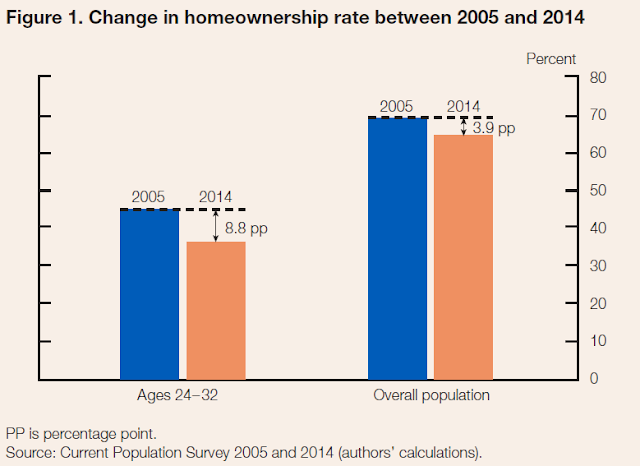

In addition, I had pointed out a Fed study which concluded student loans are creating headwinds in the rate of home ownership. The same financial burdens are likely to restrain the savings capacity of this generation, which will affect their demand for equity investments.

On the other hand, don’t be too surprised if American political discussion shifts to the left over the next decade, just as the 1960’s and 1970’s was a period of leftward drift and political turmoil in the US. As Millennials age and flex their political muscle, the likes of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortes, who is already a Millennial political star, expect economic theories like Modern Monetary Theory to assume a more prominent role in policy discussions. While I have no strong believes as to whether MMT is the correct approach, I do expect a greater fiscal boost should it become adopted. At worse, MMT would be no worse than Arthur Laffer’s supply-side theory which underpinned much of fiscal policy starting with the Reagan years.

In short, demographics isn’t destiny. Expect some headwinds for Millennials from a tougher competitive environment and higher debt burdens. On the other hand, don’t be surprised at a political blowback as this generation flexes its political muscle.

History doesn’t repeat, but it does rhyme.

What has not changed in 5000 years is human nature. We are different, but we have fear and desires, we age and this changes us. But I think this is why it all rhymes, because at the heart of it all, we are all of the same cloth

Well as Churchill said, if you are young and not liberal you have no heart. If you are old and not conservative you have no brain. I think millennials are going through their phase in life.

My understanding of MMT is that it is not simply post-Keynesian, it is something very different, and it would be almost unrecognizable to Keynesians.

First we start with an important formula in macro economics, (I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0. (I – S) = private sector balance; (G – T) = public sector balance; (X – M) = foreign sector balance. It is usually written in the form (G – T) = (S – I) – (X – M).

In the MMT framework, governments are not constrained by revenue (taxes), meaning the governments can spend way more than they currently are. For an isolated country with no foreign trade, (G – T) = (S – I) , meaning that government deficit results in private wealth. The interest payments governments make, are considered private income. So MMT proposes that govts can and should go into deficit spending to boost private wealth (job guarantee programs for example).

Note however, MMT still faces constraints, namely, real constraints, ie, inflation. MMT understands that as soon as you inject a ton of funds into a closed system, it will drive inflation up, but they have an answer to this: Taxes, very high taxes on the higher income groups, to bring the excess money out of the system.

So far, it is an internally coherent theory and fit all the presently fashionable political demands from the masses, there is just one problem: the economy is not a closed system and foreign trades exist.

Broadly speaking, countries both import and export, some countries are import oriented and some export oriented. Generally, when people become richer , they consume more, it might not be too big of a problem for a country that is largely self sufficient and can consume w/e they produce, but for an import oriented country like USA, this creates another problem.

When Americans consume more, they import more, meaning the trade deficit gets bigger, which in turn, tends to devalue their currency (despite the fact that USD is a global reserve). This creates pass-through inflation, ie, the nominal price needs to rise enough to offset the weakening of the USD. So no, in a non-closed system, the threat of inflation is very real regardless of the taxation policies they put in.

Some MMT scholars have argued that they could fix the exchange rate so that pass-through inflation is not as likely to occur. Given the Impossible Trinity and MMT relies on sovereignty of monetary policies, with fixed exchange rate being the desired outcome here, it necessitates strict capital flow control, meaning, it would result in a country that operates as capitalism on the surface, but relies on the central bank and strict capital flow control to combat inflation, while relying on the fiscal side to inject and remove funds to boost economy.

I arrived at this conclusion independently and thought it couldn’t possibly be right, but sure enough: Bill Mitchell, a proponent of MMT, wrote Why capital controls should be part of a progressive policy to substantiate my interpretation. http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=33943