December is the season for investment advisors and portfolio managers to meet with their clients. Here are some thought on your an allocation framework as you prepare for those meetings. As a cautionary message, let’s begin with a “buy and forget” portfolio featured in Fortune in 2000 and how they performed by 2012.

Haha. Experienced portfolio managers and advisors don’t make those kinds of mistakes. We all know that diversification is the only free lunch in investing.

For the simple answer on personal investing, I refer readers to a Business Insider article by Chelsea Brennan, “I spent 7 years working in finance and managed a $1.3 billion portfolio — here are the 5 best pieces of investing advice I can give you”:

- Understand your goals

- Index fund investing is the easiest way to win

- Be in it for the long term

- Don’t assume you have it all figured out

- Be prepared for anything

Unfortunately, I see American investors making the diversification mistake, as well as mistakes 4 and 5 again and again. Much of what passes for financial planning in the US is based on the mistaken assumption of a backtest that has severe survivorship problems. This will becoming increasingly evident as American policy changes from the era of Pax Americana to America First.

The long term record

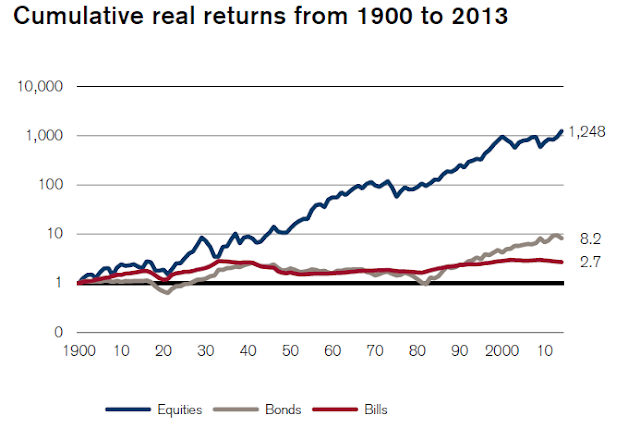

Tiho Brkan pointed out that when US investors make their investment allocation decisions, they often consider this familiar chart of the record of equity returns. Looks pretty good, right?

If you went into a client meeting in most industrialized countries with that chart, you would have been laughed out of the room. That’s because if you step back more years, and the return pattern is less familiar and feels distinctly uncomfortable.

America ascendant

Here is the survivorship problem. A bet on US equities in the last 100 years has been a bet on Pax Americana. Morgan Housel explains what happened in a rather long article:

This is a short story about what happened to the U.S. economy since the end of World War II.

That’s a lot to unpack in 5,000 words, but the short story of what happened over the last 73 years is simple: Things were very uncertain, then they were very good, then pretty bad, then really good, then really bad, and now here we are. And there is, I think, a narrative that links all those events together. Not a detailed account. But a story of how the details fit together.

The entire article is well reading in its entirety, but here is a brief summary:

- August 1945, World War II ends: The fear at the time was another Depression. What was America going to do with all of those men coming home from the war? How were they going to find jobs?

- Low interest rates and the birth of the American consumer.

- Pent-up demand for stuff led to a credit boom and a hidden 1930s productivity boom led to an economic boom.

- Gains are shared more equally than before: The defining characteristic of economics in the 1950s is that the country got rich by making the poor less poor.

- Debt rose tremendously. But so did incomes, so the impact wasn’t a big deal.

- Things start cracking in the early 1970s: America dominated the world economy in the two decades after the war. Many of the largest countries had their manufacturing capacity bombed into rubble. But as the 1970s emerged, that changed. Japan was booming. China’s economy was opening up. The Middle East was flexing its oil muscles.

- The boom resumes, but it’s different than before: All that matters is that sharp inequality became a force over the last 35 years, and it happened during a period where, culturally, Americans held onto two ideas rooted in the post-WW2 economy: That you should live a lifestyle similar to most other Americans, and that taking on debt to finance that lifestyle is acceptable.

- The Big Stretch. the internet after that: The lifestyles of a small portion of legitimately rich Americans inflated the aspirations of the majority of Americans, whose incomes weren’t rising. A culture of equality and Togetherness that came out of the 1950s-1970s innocently morphs into a Keeping Up With The Joneses effect.

- Once a paradigm is in place it is very hard to turn it around: The post GFC hangover sets in.

- The Tea Party, Occupy Wall Street, Brexit, and the rise of Donald Trump each represents a group shouting, “Stop the ride, I want off.”

While what Housel described was American economic history in the post World War II period, the US boom really began when the Great Powers battled each other to exhaustion in World War I, while the US economy remain largely unscathed.

Stocks for the long run? Just ask the Germans how their asset classes fared since the start of the 20th Century.

For some perspective, an American investor would have made over 1200 times their money in real terms if they had invested in equities between 1900 and 2013.

The French fared as well as the Germans in total return, but with less drawdown. Still, returns paled when compared to US assets.

China, which is a major global engine of growth today, suffered considerable dislocation after Mao’s victory and didn’t turn around until recently.

Bottom line: US equities should behave as they have in the last 100 years as long as there is no permanent loss of capital (see China, or undiversified bets such as the Fortune buy-and-forget portfolio), or a loss of the US competitive advantage.

The effects of America First

Here is where Trump’s America First policies pose a threat to long-term equity returns. Before we begin, I would like to preface these remarks by pointing out that Morgan Housel’s history of the post-War America shows that the problems of populism did not just originate with Donald Trump. Trump’s ascendancy is just one manifestation of the problems that plague American society.

American foreign policy has pivoted from the US as the leaders of the free world, which I call the Pax Americana model, to a win-lose world view. Why should Americans maintain troops to protect Europe, South Korea, or other countries around the world? Why does Article 5 of the NATO treaty matter? In effect, Trump is trading off the soft power of America to focus on hard power, based on the principles of America First.

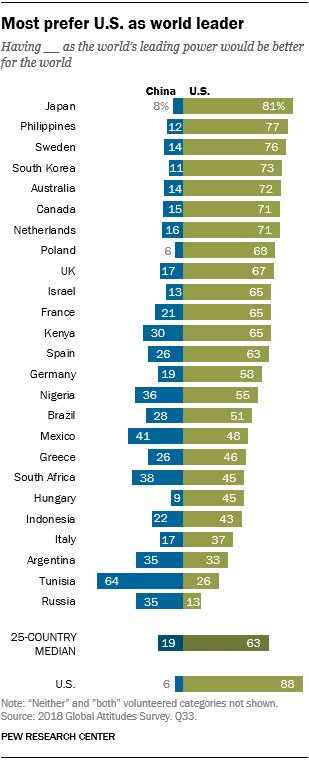

Even as Trump withdraws from global leadership, A recent Pew Research Center poll shows that the residents of most countries prefer the old world order of American leadership over one dominated by China.

Does soft power matter? As an example, the accounts from Brookings show that China is trying to develop its soft power by attracting foreign students to its universities [emphasis added]:

In a classroom adorned with Mandarin characters. They are not studying in Nairobi but at China’s prestigious Peking University. The Kenyan students explain how China has given them full scholarships to receive educational opportunities they are deprived of at home and how they will gain skills they can take back to enrich their own countries.

China is keen to promote itself as a benefactor of international students. On the other side of the Pacific, the United States—the country that has actively inspired the world’s smartest and most curious students to come study on its shores for generations—seems to be moving in the opposite direction. Through a series of policies and actions, the Trump administration is driving foreign students away from the United States. Chinese students themselves only narrowly avoided being victims of a total ban pushed by Trump staffer Stephen Miller. China views this accelerating trend as an opportunity to fill the gap. In many parts of Africa and Asia, this change is already underway. And as foreign students pick Chinese campuses over U.S. ones, a critical element of America’s soft power is in danger of being eroded.

The United States is still the world’s hub when it comes to higher education. In 2016, more than 1 million international students enrolled at U.S. colleges and universities, while fewer than half a million studied in Chinese higher education institutions.

But China’s outreach to students in African and Asian countries, especially in developing regions where it has growing economic ties, so far has been highly successful. In 2016, over 60 African and Asian countries sent more students to China than to the United States. Laos, for example, sent 9,907 students to China and only 91 to the United States. The disparity holds true for countries farther afield: Algeria, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, and Zambia sent more than five times the number of students to China than to the United States. Since 2014, the total enrollment of African students in China has surpassed that of the United States. In 2016, China hosted more than 60,000 African students, which represented a 44-fold increase over the year 2000.

At the same time as China has endeavored to expand its international higher education system, the U.S. government has scaled back its financial commitments. The Fulbright Program, a hallmark of U.S. cultural diplomacy since 1946, has faced calls for funding cuts since the Obama administration. Generations of participants—who are sponsored by the U.S. government—have gone on to important positions in academia, politics, think tanks, journalism, arts, and business around the world. Despite this impressive legacy, the Trump administration recommended a 71 percent reduction in funding for the program in its 2019 budget proposal.

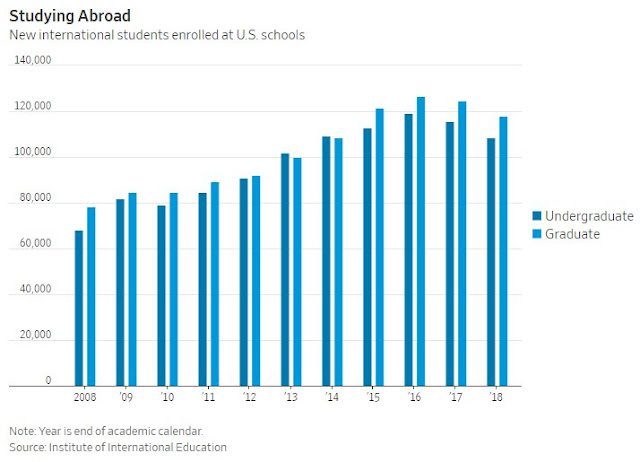

The WSJ reported that foreign student enrollment is falling in the US:

“Students are not feeling welcome in some states, so they are looking beyond those states and heading to places where they will feel welcome,” she said.

The slowdown comes as U.S. schools struggle with demographic and revenue challenges due to the falling number of Americans graduating from high school. As a result, U.S. colleges and universities have become increasingly dependent on revenue generated from international students. Public schools often charge international students more than what domestic students pay.

The U.S. is also losing students to English-speaking countries such as Canada, Australia and the U.K, which have all seen growth in the past year.

“We’re hearing that they have choices; we’re hearing that there’s competition from other countries,” said Allan E. Goodman, president of the Institute of International Education.

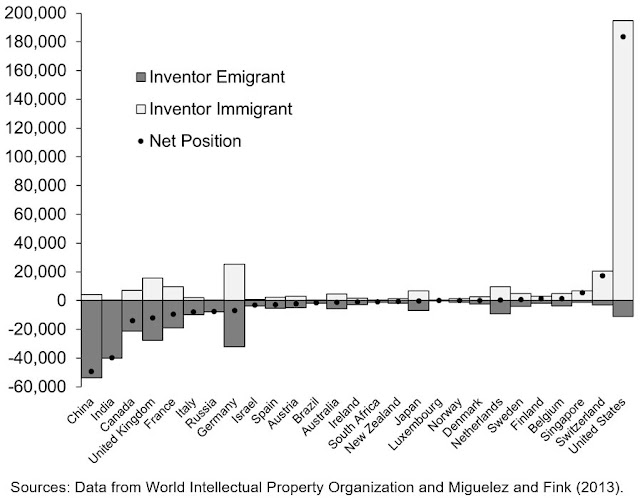

As the US closes its borders to immigrants, the dynamism of the economy becomes visibly hobbled by the barriers erected to international students, who study at top US schools and who stay to startup new businesses. Bill Kerr, D’Arbeloff Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, documented how the US has been an enormous beneficiary of inventor talent flow over the years.

Kerr wrote: “These inflows have reshaped US innovation in advanced technology sectors. The contribution of immigrants to sectors like computer science and biotech have increased dramatically over the past 40 years.”

Where will the immigrants come from to found next Intel, Apple (Steve Jobs’ father was a Syrian from Aleppo), or Google? Can Pax Americana survive America First, which looks like a policy of short-term gain for long-term pain?

This is a point to ponder as investors review their long-term investment plans.

Cam–This seems to imply that we should be looking abroad for investments long term–until Trump is no longer President. How much things will change after he is a bad memory is of course very hard to know.

Hi Cam,

I remember that you have brought up these points in the past. I remember especially when you had done a blog on German and Russian stocks before and after, WWII and Russian revolution, respectively. This seems to imply we might be in 1939. I know you are not recommending that necessarily, but I get the point, being in love with one market can be a disaster. Thanks for bringing this point back to the forefront again.

I don’t want to give the impression that this is 1939, or any year. Your takeaway should be that if the US continues to move away from Pax Americana, LT returns are likely going to become more volatile and decline. It took the UK two world wars before it lost its status as a major world power and the de facto reserve currency.

“The best government is one which limits the damage that bad men can do, rather than one which empowers good men to achieve the greatest outcome” – the American founders understood this very well, and instituted a system that was inherently error correcting. The real damage Trump can do is to corrupt the checks and balances in the system. In the long term, democracy error corrects. (…. small solace of course…. in the long term we are all….)

There are some long term factors affecting US equities.

Not being at ground zero for WW1 and WW2

A credit expansion that started 70 years ago and was preceded by the crash of 29 so the starting point was low. It makes me think of “housing prices have never gone down all across the country”

Demographics

Blocking our borders to immigrants.

There is luck which can make you feel so smart and there are bad policies.

All this credit expansion cannot go on forever…I am worried