Preface: Explaining our market timing models

We maintain several market timing models, each with differing time horizons. The “Ultimate Market Timing Model” is a long-term market timing model based on the research outlined in our post, Building the ultimate market timing model. This model tends to generate only a handful of signals each decade.

The Trend Model is an asset allocation model which applies trend following principles based on the inputs of global stock and commodity price. This model has a shorter time horizon and tends to turn over about 4-6 times a year. In essence, it seeks to answer the question, “Is the trend in the global economy expansion (bullish) or contraction (bearish)?”

My inner trader uses the trading component of the Trend Model to look for changes in the direction of the main Trend Model signal. A bullish Trend Model signal that gets less bullish is a trading “sell” signal. Conversely, a bearish Trend Model signal that gets less bearish is a trading “buy” signal. The history of actual out-of-sample (not backtested) signals of the trading model are shown by the arrows in the chart below. The turnover rate of the trading model is high, and it has varied between 150% to 200% per month.

Subscribers receive real-time alerts of model changes, and a hypothetical trading record of the those email alerts are updated weekly here. The hypothetical trading record of the trading model of the real-time alerts that began in March 2016 is shown below.

The latest signals of each model are as follows:

- Ultimate market timing model: Buy equities

- Trend Model signal: Neutral

- Trading model: Bearish

Update schedule: I generally update model readings on my site on weekends and tweet mid-week observations at @humblestudent. Subscribers receive real-time alerts of trading model changes, and a hypothetical trading record of the those email alerts is shown here.

A complacent market

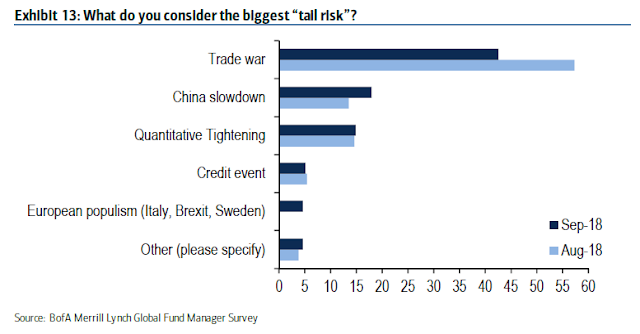

The latest BAML Fund Manager Survey shows that the biggest tail risk is a trade war, followed by a China slowdown. In reality, both are related because the risk of a China slowdown is heightened by the Sino-American trade war.

At the same time, the US trade deficit is rising, and so are trade tensions.

It is therefore a puzzle why the market has largely been shrugging off the threat of rising protectionism.

No off-ramp

Notwithstanding the laughter of seasoned diplomats, I believe the most defining moment of Trump’s address to the United Nations General Assembly was his assertion of his America First policy, “We reject the ideology of globalism and we embrace the doctrine of patriotism.”

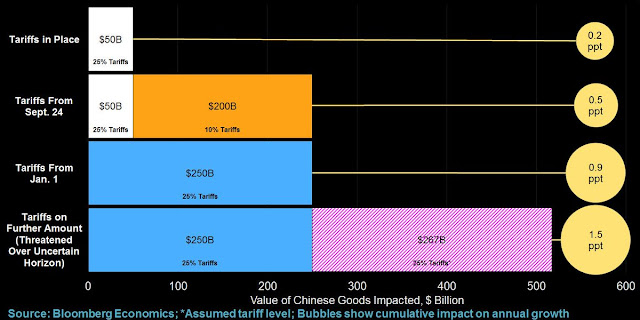

These principles that underlie his foreign and trade policy can be seen in his take-no-prisoners approach in his trade confrontation with China. When Trump imposed the latest round of tariffs on $200 billion in Chinese imports, the Washington Post reported that there appears to be no off-ramp to these negotiations:

Trump acted — accusing China of posing “a grave threat to the long-term health and prosperity of the United States economy” — even as Chinese officials weighed an invitation to visit Washington for talks aimed at ending the months-old dispute.

“The Trump administration is yet again sending a perplexing mixed message by inviting Chinese officials for negotiations and then imposing additional tariffs in the run-up to the talks,” said Eswar Prasad, former head of the International Monetary Fund’s China division. “It is difficult to see what the administration’s vision of an end game might be other than total capitulation by China to all U.S. demands.”

Gideon Rachman, wrote in the Financial Times that both sides have left little room to back down. In addition, the timing of Trump’s announcements of 10% tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese imports, which would rise to 25% rate in January was unfortunate. The announcement occurred on September 18 in China, which coincided with the start of Japanese aggression 87 years ago, which many Chinese see as an unofficial day of national humiliation. (Imagine if the Japanese had announced trade tariffs on December 7, the anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack, or Middle East countries announced another Arab Oil Embargo on 9/11.)

For political reasons, both Mr Trump and President Xi Jinping of China will find it very hard to back away from this fight. It is possible that Mr Trump would accept a symbolic victory. But Mr Xi cannot afford a symbolic defeat. The Chinese people have been taught that their “century of humiliation” began when Britain forced the Qing dynasty to make concessions on trade in the 19th century. Mr Xi has promised a “great resurgence of the Chinese people” that will ensure that such humiliations never occur again.

There is also reason for doubt that, when it comes to China, the Trump administration would settle for minor concessions — such as Chinese promises to buy more American goods or to change rules on joint ventures. The protectionists at the heart of the administration — in particular Robert Lighthizer, the US trade representative, and Peter Navarro, policy adviser on trade and manufacturing in the White House — have long regarded China as the core of America’s trade problems.

The trade conflict began as a Trump complaint about the trade deficit, and morphed into demands that China change its development model, which would be unacceptable to any country. While Trump could have followed the well-worn path followed by his predecessors by enlisting allies to object to China’s lack of intellectual property protection, that train appears to have left the station long ago.

But the US’s complaints about China are much more far-reaching than its concerns about the EU or Mexico. They relate not just to specific protected industries, but to the entire structure of the Chinese economy.

In particular, the US objects to the way China plans to use industrial policy to create national champions in the industries of the future, such as self-driving vehicles or artificial intelligence. But the kinds of changes that the US wants to see in Beijing’s “Made in China 2025” programme would require profound changes in the relationship between the Chinese state and industry that have political, as well as economic, implications.

Seen from Beijing, it looks as though the US is trying to prevent China moving into the industries of the future so as to ensure continued American dominance of the most profitable sectors of the global economy, and the most strategically-significant technologies. No Chinese government is likely to accept limiting the country’s ambitions in that way.

Even more alarming is there doesn’t to be any off-ramp to these negotiations, and both sides believe that have the superior hand:

The dangers of US-Chinese confrontation over trade are amplified by the fact that both sides seem to believe that they will ultimately prevail. The Americans think that because China enjoys a massive trade surplus with the US, it is bound to suffer most and blink first. The Chinese are conscious of the political turmoil in Washington and the sensitivity of American voters to price rises.

Former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd echoed similar sentiments in an interview with the Australian Financial Review:

The dispute has morphed into a broader “trade investment plus” fight, Mr Rudd said, which now includes the deficit issue plus demands for changes on investment rules, advanced technology transfers and intellectual property rights.

“So the levels of complexity from a Chinese negotiating perspective are massive,” said Mr Rudd, who believes there is almost no chance of an effective resolution before the US mid-term elections in early November.

“The Chinese want to know who they’re dealing with after the mid-terms; will the President be weaker or stronger?; will he make changes to the administration?; and what will be the composition of Congress?”

The Sino-American conflict could metasize into something even bigger than anyone expects:

Mr Rudd remarks come after he delivered an alarming speech in California last week in which he warned that 2018 is shaping up as a watershed year in which the world is set on a course towards another big power war.

It starts as a “trade war” that “metastasises” into a technology war that will either drive or destroy the economies of the 21st century, he said.

“It is an open question if and when this will begin to fuse into another ‘Cold War’, let alone if and when the unpredictable forces now being unleashed by this rapidly unfolding new economic war erupt into one form or other of military confrontation in the future.

“Until relatively recently, this sort of language was almost unthinkable in mainstream public policy. The problem now is that it has entered the realm of the thinkable … nobody is any longer confident where all this will land.”

Estimating the damage

What are the likely effects of a full-blown trade war? The St. Louis Fed quantified the value of exports to China by state. A full-blown trade war is likely to be painful for the American economy.

From the ground up, the effects of the trade war are already being felt. A CNBC survey revealed that 75% of CFOs expect to be affected by US trade policy.

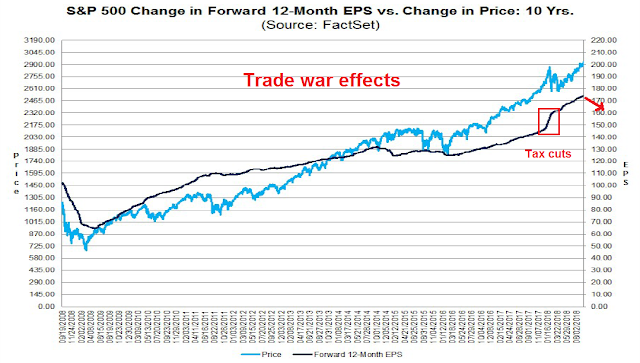

For equity investors, earnings are what matters to stock prices. Marketwatch reported that JPM estimated that a trade war would cut $8-$10 from S&P 500 EPS:

J.P. Morgan estimates that the initial round of tariffs—China and the U.S. have imposed tariffs on $50 billon of imports from each other—have so far had only a roughly $1 impact on 2018 per-share earnings in aggregate, out of roughly $30 EPS growth expected for the year. Commentary generally reflected that, the analysts said in a report.

Companies have options to mitigate the trade headwinds, including passing rising costs on to end users, altering their supply chain and production and seeking trade exemptions, they wrote.

However, “the full-year EPS headwind could increase to $8-10 under a more restrictive/severe trade scenario, which would result in significant negative revision to forward EPS estimates,” said the report.

As the chart from FactSet shows, EPS estimates tends to move coincidentally with stock prices. A cut of $8-$10 from forward EPS only amounts to about 5% of earnings. While such a development is negative, it cannot be regarded as a total disaster as it would be smaller in magnitude than the earnings boost from the corporate tax cuts.

However, the cuts in earnings are just the first-order direct effects. Bloomberg reported that the JPM analysts raised concerns about second-order effects, such as the lack of confidence:

Concerns for the markets and economy include “second-round” effects from trade battles, including hits to confidence, supply-chain disruption and and tighter financial conditions, the report said. It noted that improvements at the country level in key markets have been “incremental rather than transformational,” citing Turkey, Russia, Brazil and Argentina.

Indeed, Bloomberg reported that former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson warned about the long-term damage to business confidence from Trump’s trade policies:

A trade war with China carries “dangerous” long-term risks because companies and nations may pull back from doing business with the U.S., former Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson said…

“The question really is: Is China going to start looking for new markets for which they’re going to buy soybeans?” Paulson said Thursday in an interview with Bloomberg’s David Westin, suggesting it might turn to Brazil or Africa. “Are they going to be concerned that they need to protect themselves if there’s another tariff war and they need other suppliers?”

“Companies and countries want to do business with the United States because we’ve got reliable, stable economic policies,” Paulson said. “Are they going to want the U.S. to be a supplier if they think the United States is going to come in and break up the supply chain? Is a foreign investor going to want to come in and build a plant in the United States if they’re afraid they’re going to be in the middle of a tariff war?”

There are signs that business confidence is fading. CNBC reported that the trade war is spooking CEOs into scaling back investment plans:

The Business Roundtable found that nearly two-thirds of chief executives said recent tariffs and future trade tension would have a negative impact on their capital investment decisions over the next six months. Roughly one-third expected no impact on their business, while only 2 percent forecast a positive effect.

The group’s quarterly survey also showed plans for hiring dropped as well, falling almost 3 points from the previous quarter to 92.6. But expectations for sales rose 2 points to 132.3.

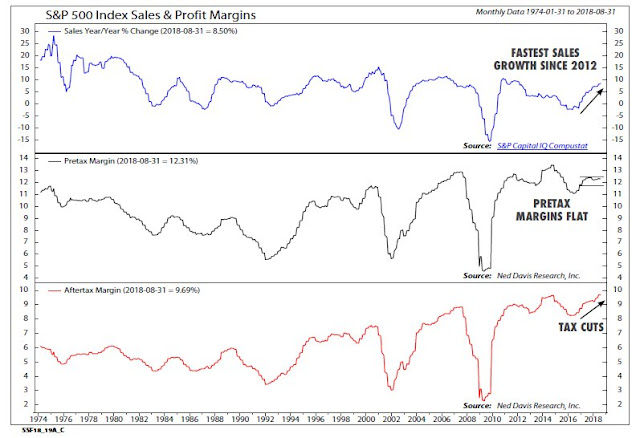

Still, that’s not the entire story. Ed Clissold of Ned Davis Research observed that the surge in 2018 earnings was not just a tax cut story. While net margins (bottom panel) rose in 2018 because of tax cut effects, pretax margins (middle panel) were flat. At the same time, sales (top panel) were up 8.5% year/year, which was part of the reason for rising earnings. Sales growth is likely to slow from these levels in 2019. A more reasonable assumption would see sales rise at the nominal GDP growth rate of 4-5%, excluding currency effects. If sales were to slow even further because of the direct effects of a trade war, and loss of business confidence, investors will need to prepare for the downside effects of operating leverage on earnings.

Here is what might happen to sales growth under a full-blown trade war, as measured by real GDP growth. Oxford Economics projected the impact over the next few years, with far ranging effects all over the world.

Indeed, bottom-up earnings estimates for China and Japan are already weakening, though US estimate revisions remains strong for the moment.

The Fed’s reaction

Assuming that Oxford Economics forecast is correct. Here is the likely Fed reaction function to a trade induced slowdown. The 0.1% hit to 2018 growth would not appear in the economic statistics until the middle or late Q1 2019. The Fed is likely to dismiss those effects as transitory. It would promise to monitor trade effects, and continue with its rate normalization program.

In the post-FOMC meeting press conference of September 26, 2018, Fed Chair Powell diplomatically skirted questions about trade by stating that the Fed is not responsible for trade policy. He added that they were “hearing a rising chorus of concerns from across the country” about tariffs, supply chain disruptions, and rising input costs. He downplayed the effects of the tariffs so far as “you don’t see it yet”. These statements make it clear that, despite the well-known evidence of rising tit-for-tat tariffs, the Fed is not prepared to look ahead and will only react to changing conditions after the fact.

The full effects of the trade war would not become evident until late 2019. By the time the Fed begins to react by loosening monetary policy, it will be too late. Add the trade-induced slowdown to the effects of monetary tightening, as well as the fade of the tax-cut sugar high, the odds of a recession rises rapidly.

As a reminder, recessions have a 100% success rate as equity bull market killers.

The week ahead

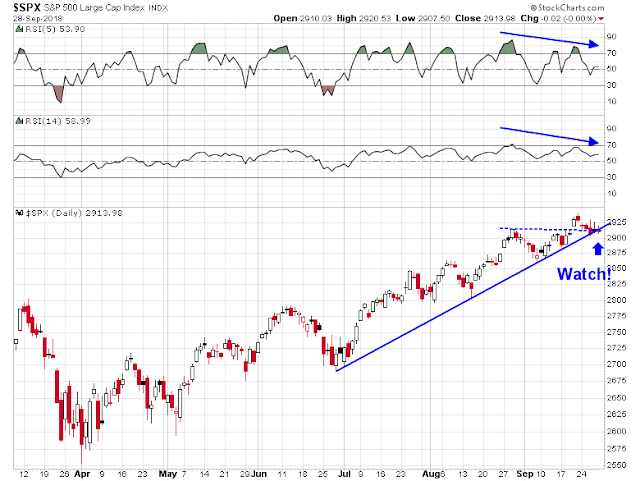

Looking to the week ahead, the S&P 500 weakened last week to test a key uptrend line while exhibiting negative RSI divergences, indicating that the path of least resistance is down. So far, the trend violation is minor, a decisive break would be a signal that the bears have taken control of the tape.

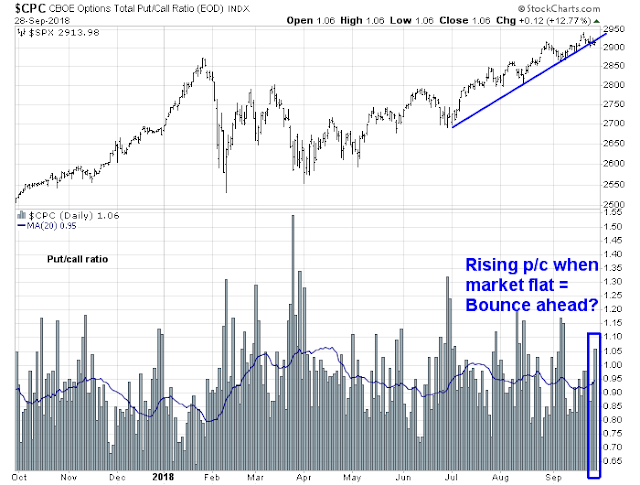

In the short-term, option sentiment is tilted bearish. The market closed flat on Friday, but the CBOE put/call ratio rose, indicating rising bearishness, which is contrarian bullish.

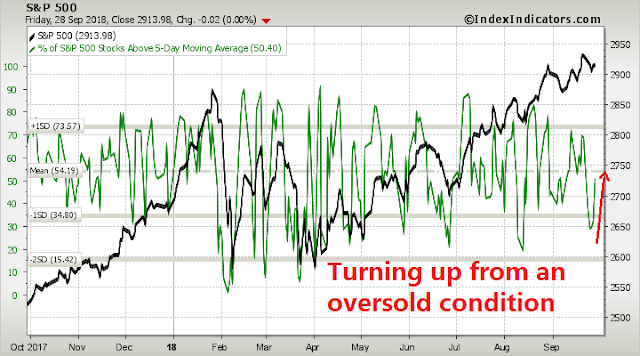

As well, short-term breadth indicators were oversold but exhibiting positive momentum. This suggests that the market will bounce early next week, followed by another test of the rising trend line soon afterwards.

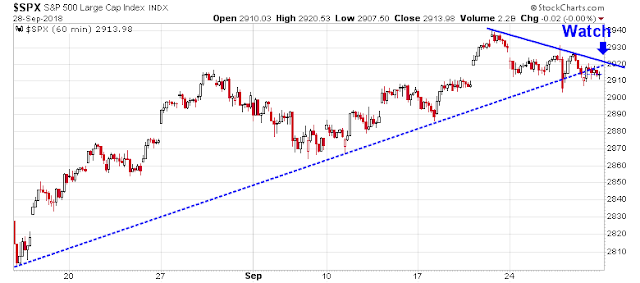

From a tactical perspective, the hourly chart shows the marginal break of the uptrend (dotted line). Upside resistance can be bound at the descending trend line at about 2920, which is one spot that the bears will have to make their stand.

My inner investor is cautious, but not outright bearish on stocks. He is therefore maintaining a slight underweight equity position relative to their target weights specified in his investment policy statement (you do have an IPS, right?).

My inner trader entered last week short the market, but his commitment was relatively light because of numerous binary market-driven events, such as Trumps visits to the UN, the UN Security Counsel, the FOMC announcement, the potential for a government shutdown, and the deadline for a NAFTA deal with Canada. He expects to add to his short positions next week on a rally early next week or on a decisive break of the rising uptrend.

Disclosure: Long SPXU