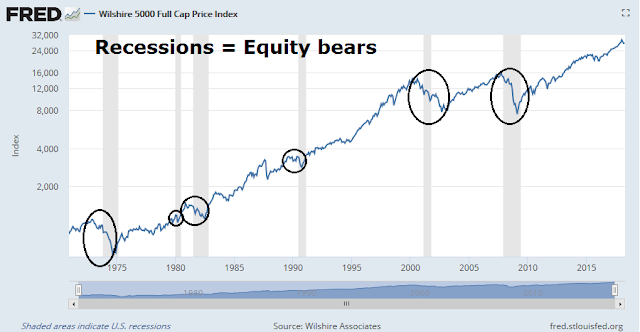

Historically, every recession has been accompanied by an equity bear market.

One characteristic of every recession has been a credit crunch. As the economy slows, banks react by tightening their lending criteria, which dries up the availability of credit, and eventually causes a credit crunch. There are a number of ways that investor can monitor the evolution of lending standards.

The most obvious way is to watch the Fed’s lending officer survey. The latest data shows that readings remain benign for both corporate and individual borrowers. One disadvantage of the survey is the results only come out quarterly, which is not very timely and amounts to looking in the rear view mirror.

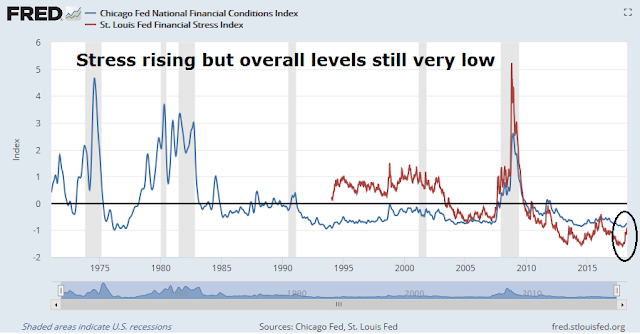

A more timely data series are the Chicago Fed`s Financial Conditions Index, and the St. Louis Fed`s Financial Stress Index. Current conditions show that Stress levels are starting to rise, though the absolute stress levels remain low. Both of these data series are released monthly, which is more timely than the lending officer surveys.

There may be a better real-time way of watching for a credit crunch.

Tesla: The canary in the credit crunch coalmine

One of the functions of recessions is to unwind the excesses of the previous cycle. The finances of Tesla (TSLA) is the poster boy of the this expansion. Recently, Tesla CEO Elon Musk shot back a reply to an article in The Economist which indicated that the company needs to raise $2.5b to $3b this year as it continues to burn cash.

Much of the controversy surrounding TSLA hinges on whether the company can produce its mass market Model 3 cars in size. The latest lawsuit, which features a number of accounts from former employees, sheds light on that Herculean task. Here are just a few highlights from the lawsuit, starting with the key claims:

16. In May 2017, when Defendants stated that the Company was “on track” to meet its mass production goal, as production on a fully automated production line was supposed to be ready to begin, and in August 2017, when production on a fully automated production line was supposed to have already been in place and Model 3s were supposed to be coming off the line, according to a number of former employees, the Company had not yet finished building its automated production lines in either Fremont or Nevada. Tesla was neither ramping up mass production, nor “on track” to mass produce Model 3s at any time on or around the end of 2017.

17. Defendants Musk and Ahuja, who visited the Fremont facility on a regular basis, knew that the Model 3 production line was way behind the publicly announced schedule and that it would never mass produce the Model 3 in 2017.

18. As Defendants claimed to be on track for mass production in 217, the Fremont facility was assembling Model 3s, by hand , in the “beta” or “pilot” shop,” a facility to assemble prototypes. The actual mass production line at Freemont was yet to be completed. Workers in the pilot shop were not even able to build enough Model 3s to carry out the necessary testing on the vehicles, and most Model 3 workers were being reassigned, or spending their days cleaning. It was evident to anyone who visited the Fremont facility – and Musk himself visited the unbuilt production line area every Wednesday, known internally as “Elon Day” – that the production line was not yet built, that parts for the necessary robots were not present, and that construction workers were spending most of their shifts sitting around with nothing to do. Multiple former employees corroborate the fact that there was no fully functioning automated production line when Tesla was telling the world that there was, and that the construction site where the line was being built was clearly and visibly far from completion.

Skipping ahead to the accounts of the former employees:

125. Some time in late April or early May of 2016, FE1 participated in a meeting with Musk, CFO Jason Wheeler, and the Vice President of Engineering. FE1 stated that during that meeting, he told Musk directly that there was zero chance that the plant would be able to produce 5,000 Model 3s per week by the end of 2017.,,

190. According to FE9, the Gigafactory was plagued by problems related to producing usable models, and the first battery model was completed long past the deadline when the Model 3 was supposed to have been launched. The process required apply adhesive at a specific ratio, which if not done properly caused the batteries to “fall off.” Parts and spaces between parts were small, making correct module completion challenging. FE9 stated that prior to automated production, human error resulted in poorly produced modules “all the time,” with workers rushing products through the line, assuming problems “would fix [themselves],” which they did not…

195. During FE9’s tenure, which lasted almost to the end of the Class Period, the Gigafactory produced no more than two battery packs at most per day, sufficient for two cars. Realistically, it took a full day – comprised of two shifts – to produce a single battery pack, and, even then, it was not a “customer saleable pack,”, i.e., a pack that passed inspection and was ready to be installed in the Model 3.

196. The only “customer saleable pack” was completed in October 2017, shortly before FE9 left Tesla. A company-wide email was sent congratulating the engineers and production workers for their hard work.

Really? And the battery Gigafactory is TSLA’s competitive moat?

For some perspective of TSLA’s production problems, FT Alphaville reported that Max Warburton of Bernstein Research diagnosed the company’s problems as trying to automate before perfecting the production process:

What is the inspiration behind Tesla’s automation? Tesla has bought German robots and a German automation company (Grohmann). But the German OEMs – traditionally the most enthusiastic proponents of automation – have actually been rowing back on it in recent years. The best producers – still the Japanese – try to limit automation. It is expensive and is statistically inversely correlated to quality. One tenet of lean production is “stabilise the process, and only then automate”. If you automate first, you get automated errors. We believe Tesla may be learning this to its cost.

In other words, TSLA is never going to fix its production problems, and it will continue to burn cash. The latest report from Reuters that the company is pausing production for several days to fix its production problems is not helpful to its bull case. The only thing keeping the company’s finances in shape is Elon Musk’s flair at selling his vision to investors.

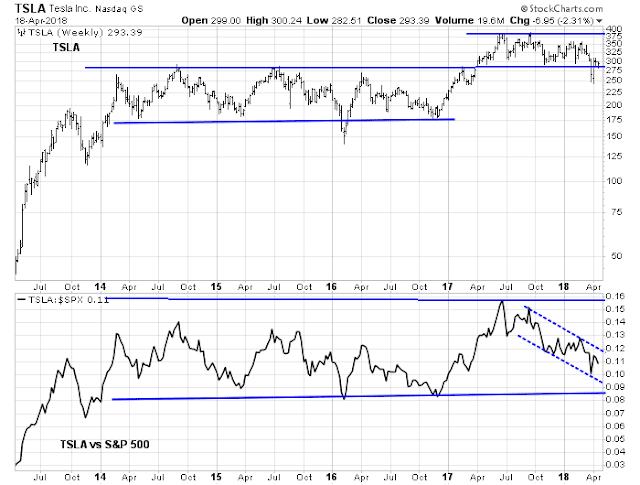

So what happens when the animal spirits turn and banks tighten their lending standards? That bring me up to my point. While I am not an advocate for either selling or shorting TSLA, I believe that the stock is the canary in the credit crunch coalmine for this market cycle.

The chart of the stock price shows two ranges, with the stock in the lower part of a higher range. However, the lower panel of the chart shows that the stock remains range bound relative to the market, though the stock is tracing out a minor falling channel.

Should it break the relative range to the downside, that would be a signal to batten the hatches.

Disclosure: No positions

very good article!!!

Do you have any options on TSLA as a short trade?

I would hesitate to short TSLA. These kinds of things have a way of not mattering until they matter.

Good theory on TSLA, Humble. Very impressive.

So, Tesla may be the poster child of cheap capital making rounds of bubbly companies (circa 2008, American banks fit the bill, Lehman was the poster child, I suppose) . What other companies fit the bill?

Thanks.