When I was a boy, I can remember the Zero Population Growth (ZPG) movement, which was a response to the Club of Rome‘s Limits to Growth Mathusian thesis of “the world has limited resources, but human population is rising exponentially and therefore ecological disaster looms”. Somewhere along the way, birth rates fell in response to global industrialization, rising incomes and changing incentive structures. In an agrarian society, children are potential units of production. They can be put to work in the fields and support you in your old age. In an industrialized society, children are cost centers. It was no wonder that birth rates fell as the emerging market economies boomed.

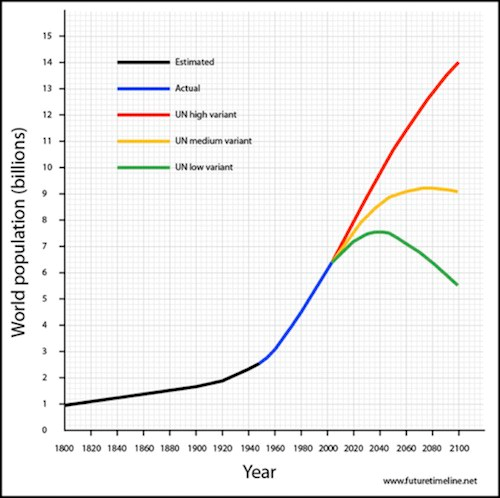

Today, ZPG has been realized (and more). Human global population will stabilize and shrink some time in the 21st Century. In fact, global population is about to reach an inflection point in the not too distant future as the number of old people will soon exceed the number of young children (via Business Insider):

A demographic shift like this raises all sorts of questions. For investors, it brings into the question of future returns as Baby Boomer demand for retirement income starts to dominate capital market returns and strain government retirement benefits. For policy makers worldwide, the issues are how to fund retirement benefits, as well as how to structure policies to transition to an aging society.

The looming retirement crisis

John Mauldin addressed many of these issues in his essay Welcome to the Pale Grey Dot. The world is indeed aging and it will cause a retirement crisis. The only question is one of timing.

Mauldin, who has preached a gloom-and-doom message for as long as I can remember, painted a dire picture of what is likely to happen in retirement:

I’ve said this before, but it’s worth repeating: “retirement” is a new concept. For most of human history, people worked as long as they were physically able and died soon thereafter. And in much of the world that is still the case. Traditionally, the intervening period between no longer being able to work and dying was longer for people who had large families to care for them – which is one reason fertility rates were so high.

This state of affairs began to change in the 19th century when the advent of mechanized agriculture began to allow a farmer to feed his own family and still have food to sell. The work time of farm families was somewhat freed up, and more time could be devoted to helping the elderly to live longer.

At some point, supporting retirees went from being a family responsibility to a task shared between family and society. Governments created programs like Social Security in the US that guaranteed some minimal income to older folks. Businesses did the same with pension plans. Families were still the backstop, though, along with whatever savings retirees had accumulated.

For a century or so, this three-legged stool worked fairly well. People who reached retirement age could stop working and lean on some combination of (a) their family (mainly their children), (b) their own savings or pensions, and (c) government

Now that’s starting to change. By choosing to have fewer children, we unwittingly sawed one leg off that three-legged retirement stool. It’s hard to depend on descendents who don’t exist.

Worse, the other two legs are starting to crumble, too. Defined-benefit pensions are rare in the private sector and unstable for government retirees. Individual investors tend to lose their money in market crashes and are often lucky just to break even. Even government plans like Social Security are in increasingly questionable shape.

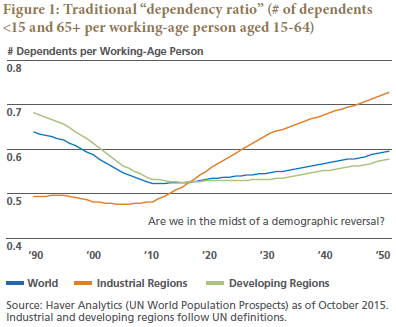

Matthew Tracey and Joachim Fels at Pimco have a more sanguine view in their essay 70 is the new 65. They argue that the traditional way of thinking about dependency ratios, like this chart below, is all wrong.

Instead, they calculate a modified dependency ratio based on a re-defined “peak savers” and the saving activity of seniors as they age, as life expectancy have risen. Based on these calculations, the demographic cliff is delayed by about ten years.

An asset-liability framework

I believe that the focus by Mauldin, Pimco and many other analysts on the coming demographic cliff is overly myopic as it only shines the spotlight on the social liability side of the equation. If we view the problem using an asset-liability framework, the bigger question is how society as a whole responds to an aging population.

- How can society generate sufficient wealth and growth to provide for its swelling number of seniors? The problem about rates of return on invested pension assets and pension funding ratios are issues of how to split the inter-generational pie. That question will become a matter of social debate that likely gets decided at the ballot box. Unless the pie is big enough and growing fast enough, nothing matters.

- Equally important and related to my previous point about the size of the pie: How will businesses respond in the face of a shrinking global labor pool?

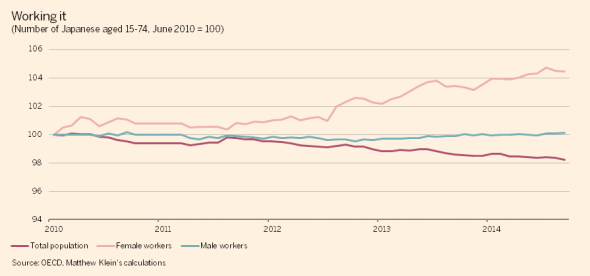

We can get some clues from Japan, which is an advanced industrial society with the oldest population profile. Matthew Klein at FT Alphaville documented the two ways that Japan has responded to its aging population profile. First of all, employment rates went up, which was no surprise:

They enlarged their labor force, as female participation rose. As an aside, labor force enlargement could also be accomplished through higher immigration, but Japan did not go down that road.

In a separate FT Alphaville post, Klein demonstrated that the US could also enlarge its labor force through better female participation. Just look at the gulf in female participation rate between American and Canadian workers. Bloomberg also reported that an increasing number of Americans plan to work until 70, which also raises the size of the work force.

In addition, Japanese corporations invested – a lot. True, the Japanese household savings rate collapsed just as its demographic profile predicted.

But the current account soared, as Japanese corporations raised their savings rate and invested overseas.

Demographic Apocalypse Not Yet – even in aging Japan.

The robots take over?

The Japanese experience brings up an important point about capital and labor. Duncan Weldon, writing in Medium, recently asked “How does capital respond to a labor shortage?”

An article in the Wall Street Journal last week got me thinking again about of the bigger medium term questions in macroeconomics. Namely, what should we be worrying about more: not enough workers or not enough jobs?

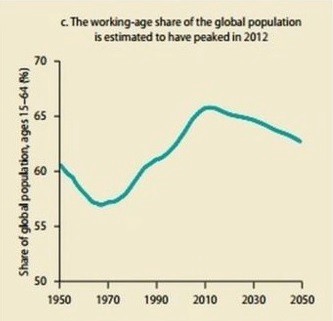

On the one hand, the world is undergoing a demographic transition and the one off impact of China’s entry into the global economy may have run it’s course.

If I had to pick one graph to show “what’s happening in the world right now”, this one would be pretty high up my list:

Weldon found the answer in how Arizona businesses responded to a labor shortage. The answer was automation:

The WSJ article that helped clarify my own thinking was on Arizona and the impact of a multi-year crackdown on illegal immigration. The state provides a neat case study of what happens when a labour shortage develops.

At first glance the numbers appear to back up the Goodhart-Nangle argument:

As the Arizona economy recovered, a worker shortage began surfacing in industries relying on immigrants, documented or not. Wages rose about 15% for Arizona farmworkers and about 10% for construction between 2010 and 2014, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Some employers say their need for workers has increased since then, leading them to boost wages more rapidly and crimping their ability to expand.But faced with a shortage of workers and rising costs, capital responds. The labour market doesn’t operate in vacuum.

Here’s how on Arizona pepper farmer has responded:

He says mechanization is his future. He continues to pour time and money into a laser-guided device to remove stems from peppers, which pickers now do by hand in the field. Another farmer in the area developed a mechanical carrot harvester.

Mr. Knorr says he is willing to pay $20 an hour to operators of harvesters and other machines, compared with about $13 an hour for field hands.

Take away cheap labour and business models that rely on it existing will adapt or die. The way to adapt is to investment in labour-saving technology.

Even Foxconn has followed this well-trodden path by firing 60,000 Chinese workers and replacing them with robots (via the BBC):

In a statement to the BBC, Foxconn Technology Group confirmed that it was automating “many of the manufacturing tasks associated with our operations” but denied that it meant long-term job losses.

“We are applying robotics engineering and other innovative manufacturing technologies to replace repetitive tasks previously done by employees, and through training, also enable our employees to focus on higher value-added elements in the manufacturing process, such as research and development, process control and quality control.

“We will continue to harness automation and manpower in our manufacturing operations, and we expect to maintain our significant workforce in China.”

Since September 2014, 505 factories across Dongguan, in the Guangdong province, have invested 4.2bn yuan (£430m) in robots, aiming to replace thousands of workers.

Demographics Apocalypse Not Yet,

A global inequality reversal?

So far, the trends I have outlined so far is already known. Businesses are responding to a labor shortage by investing in automation. Aggregate output will not fall. Society will be able to take care of its seniors. How it re-distributes the fruits of automation is another question that will have to get decided at a level that’s beyond my pay grade.

This brings up another, but more speculative point. Branko Milanovic pioneered a study showing how global inequality has changed over the last thirty years. Much of the gains from globalization and offshoring accrued to the middle class in the emerging market (EM) economies and the very rich of the world, because it was the top 1% that directed and reaped the fruits of globalization. The losers were the people in the subsistence economies, because those economies were not sophisticated enough to participate in the global labor rate arbitrage, and the middle class in the developed market (DM) economies.

Just look at how global income distribution has improved since 1988:

…and how poverty rates have plummeted.

As the world gets older and businesses respond with more automation, especially in an inter-connected world where technologies like 3D printing become more ubiquitous. Consider this article by James Fallow, writing in The Atlantic, about the Maker Movement, which has become a grassroots movement of (currently) artisans creating flexible manufacturing in the United States:

“This would not have been possible ten years ago,” Venkat Venkatakrishnan, the CEO of a unique and famous maker space called FirstBuild, told me in Louisville earlier this year. FirstBuild is unique because it was created by GE, as a subsidiary of its appliance division and as a deliberate effort to bring the nimble maker spirit to its design process.

“What has changed is that the maker movement has figured out a group of technologies and tools which enable us to manufacture in low volume,” Venkat (as he is known) said. Big manufacturers like GE built their business on high-volume, factory-scale, very high-stakes production, where each new product means a bet of tens of millions of dollars. FirstBuild is mean to explore smaller, faster, more customizable options.

“Now you can get a circuit board mill for $8,000. If you are looking for a circuit board for an appliance, earlier the only chance of getting it was from China. Today I can make boards here and ship them out quickly. Similarly with laser cutters—not big ones but small ones, where I can cut metal right here. It’s a huge advantage, and these things did not exist ten years from now. In those days you couldn’t hack the kind of creative solutions we are seeing now.”

Such a revolution in 3D printing and specialized manufacturing would shorten the supply chains in both distance and number of nodes. It also suggests a reversal in the labor arbitrage advantage that has benefited the EM countries in the last 30 years and the start of reshoring back to the developed markets.

If that becomes the case, global inequality is likely to increase over the next 30 years, which will be a headwind for EM investors, while the winners will be the technology leaders who stay at the top. This also would be a welcome development for the embattled middle class in the developed market economies, which has seen populism and tribalism rise, especially in Europe (see The Brexit Pandora’s Box).

To be sure, not all EM countries will lose under such an arrangement as trade patterns would shift from global to regional in nature. The countries that can offer the combination of low labor rates and proximity to markets, such as Mexico (NAFTA bloc), Eastern Europe (EU), China and South Korea (Asia) are likely to become the comparative winners within the EM economies.

We are just as blind as the Club of Rome was in the 1970s. Just as willing to fear the future.

I heartily recommend the book “The Rational Optimist”. It describes how the human race has always adapted to problems.

The digital revolution will have an unimaginable impact in all areas of life. Take Healthcare. AI will aid remote diagnosis and treatment. So instead of huge future cost increases, costs will fall.

In the area of demographics when statistics say that numbers of young people versus old will fall hurting the economy, I disagree. Simply counting bodies is wrong. For example in China one digital savvy young person entering the workforce will produce more than dozens of retiring old-style farmers. Numbers lie.

Nicely put! Counting bodies of old people and the young couldn’t be more wrong in that kind of scenario. One would think that in a rapidly rising economy like China the difference between the old and the young could be significant in terms of value added.

Regarding business investment, my layman thinking is that the lack of biz investment will get remedied by rising wages and especially after several years in the doldrum new technologies may exist and finally come into the awareness of business leaders that may have pent up demand for capex spending. Thus propelling a sudden jerk of investment spending before China come crashing down with its debt load in few years time.

Happily, the demographic bulge problem — how to take care of the hordes of pensioners in the future — is oftentimes quite trivial. In Germany, all it needs is for the age of pension begin to increase by another 2-3 years. (The politics are not trivial, but the solution is).

I also find reverse migration fascinating. I know some oldish folks who have firm plans to move to Thailand when they get wobbly. There exists there a first-rate system of nursing homes for western people where you get friendly, luxury care for a fraction of what it would cost in Europe.

Anyway, Cam: quite excellent post, once again!

Hmmm. My sister is an Ontario physician and nothing the commenters here are saying aligns with what she experiencies daily or her predictions for the future of Canadian medicine and senior care (most people don’t want to live and die among strangers). Not to mention that diagnosis and treatment are very complex and emotional issues already all too inhumanly delivered in a hastiy manner with spotty follow up among too many different physicians. Euthanasia will probably play an important role in cutting down costs too but I’m not sure if that demonstrates success or failure of the system.