For your weekend contemplation: This post isn’t about how the American and Chinese economies may converge, but about the potential development path of capital markets and regulatory regimes. CNBC recently reported that Charles Schwab and the Shanghai Advanced Institute of Finance conducted a survey of Chinese stock investors and found out the reason the Chinese all appeared to be punters and gamblers. First and foremost, they didn’t start that way and only a small minority were in it for a quick profit:

Having surveyed 450 investors, only 13 percent invest for short-term purposes, such as turning a quick profit or generating enough cash to make a major purchase, while 87 percent invest as a means to improve their standard of living, retire or their children’s education, the study found.

But the Chinese market is not very mature and the investor base isn’t very sophisticated:

The lack of a mature bond market, long-term products on the market and professional financial advisors were major challenges, the authors explained.

“While the incomes and expectations of China’s emerging affluent have risen, China’s financial services sector has not kept pace…Unlike upper-middle class investors abroad, most Chinese investors chart their financial futures without assistance from financial service professionals,” the authors said.

As a result, Chinese often don’t understand the content of their investments and the risks they carry, the study noted, pointing to WMPs as an example. Detailed information isn’t always provided to customers and this lack of transparency is intentional since most WMPs are concentrated in China’s increasingly troubled industrial sector, the study said.

The combination of the lack of a professional institutional investor base (think Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund) and the lack of hard information about the markets, individual investors adopt behavior that looks like gambling:

Emerging affluent investors only invest 20 percent of their total assets in stocks due to market turbulence and aggressive government intervention forces. Because of this tiny allocation, Chinese tend to time the market, which isn’t usually a winning strategy for the average retail investor, the study noted.

“Speculative inclinations among investors are further reinforced by the disconnect between China’s stock markets and its real economic situation,” it said, revealing that only one-fifth of China’s industrial companies are listed on its A-share markets, while almost no emerging technology companies are represented.

“When a stock market fails to reflect the circumstances of the broader economy, rumor-driven speculation gains an upper-hand over strategic decision-making.”

Moreover, the incentive system of the advisors and salesman selling these investors are skewed towards sales, instead of doing the right thing for the client:

Because advisors tend to generate the majority of their revenues through sales commissions, they often sell products without regard for their clients’ needs, doing little to educate investors, according to the study.

During my tenure as an international equity portfolio manager, I observed similar kinds of punter and gambler mentality in many Asian markets. Unlike the American, European and even Japanese markets, whose trading are dominated by a local institutional investor base who tend to be more sophisticated about equity analysis, macro-economic analysis, etc., most Asian markets tend to be dominated by retail investors, whose are less knowledgeable about markets and have trading mentalities. Even “well developed” equity markets whose culture are Chinese in character like Hong Kong and Taiwan have experienced wild swings in prices on high volume turnover that are the hallmark of trader dominated markets.

Is a “westernized” market the answer for China?

Sitting here from a perch in the West, it would be easy to feel smug about the lack of market sophistication in China and the kinds of western solutions that can be applied. Even in the United States, those kinds of approaches have been problematical. The WSJ reported that, despite the widely publicized cases of wrongdoing, few individuals have been prosecuted:

The Wall Street Journal examined 156 criminal and civil cases brought by the Justice Department, Securities and Exchange Commission and Commodity Futures Trading Commission against 10 of the largest Wall Street banks since 2009. In 81% of those cases, individual employees were neither identified nor charged. A total of 47 bank employees were charged in relation to the cases. One was a boardroom-level executive, the Journal’s analysis found.

The analysis shows not only the rarity of proceedings brought against individual bank employees, but also the difficulty authorities have had winning cases they do bring.

As well, consider the resistance over the Department of Labor’s proposal for the adoption of a fiduciary standard for investment advisors (see comment above about Chinese “advisors” selling product without regard to client needs). To be sure, not all bankers are evil and many people in the industry try to do the right thing and put their clients first:

Over the years the Department of Labor spent developing and then reworking the fiduciary rule, Assistant Secretary Phyllis Borzi and her colleagues regularly received support from a surprising quarter – people who work for some of the companies that most vehemently fought it.

“Wherever I would go, people would come up to me, wearing name tags of companies that were wildly opposed to what we were doing, and they would say, ‘You go, girl,’ ” Borzi told an audience at an Institute for the Fiduciary Standard event this week. “And that kept us going.”

Like China, the incentive system has been skewed the wrong way and, as Greg Mankiw famously put it, people respond to incentives:

She emphasized that the industry’s conflict-of-interest problems come not from the people who work in it, but from the structure of the system itself.

“It isn’t,” she said, “a case of bad people giving advice. It’s that people who wanted to do the right thing by their clients were trapped in a bad system, in a system that was characterized by misalignments of the interest of the investor and the interest of the adviser.”

Should America emulate China, or China America?

I spent about half of the time in my professional career on the buy side (as an institutional investor) and half on the sell side (brokerage firm). The principal focus of my sell side career has been on institutional investors.

Here is what I found disturbing about that experience, as the fiduciary standard is arguably not relevant when dealing with institutional investors, who are trained investment professionals. Here is what I have observed first-hand:

- Salesman and traders who knowingly sell junk to clients with the justification that, “They’re all big boys and they know the risks. It’s all in the disclosure documents.”

- One salesman, a CFA charterholder himself, derided a negative research report that I wrote as the “CFA way of doing things” because it interfered with a product that he was selling. (Sorry, I thought I should adhere to the CFA code of ethics).

- An investment banker who actively hid the fact from his firm’s research arm that the CEO of a company that the firm had IPO’ed had a criminal record.

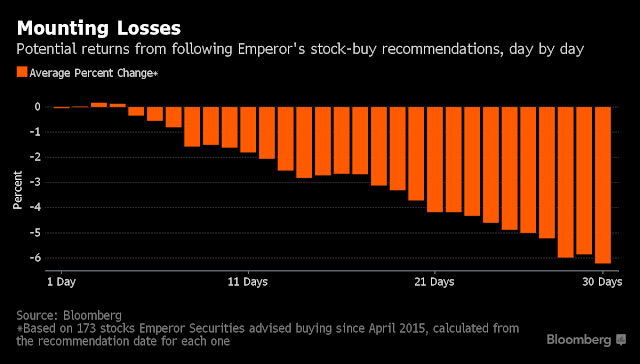

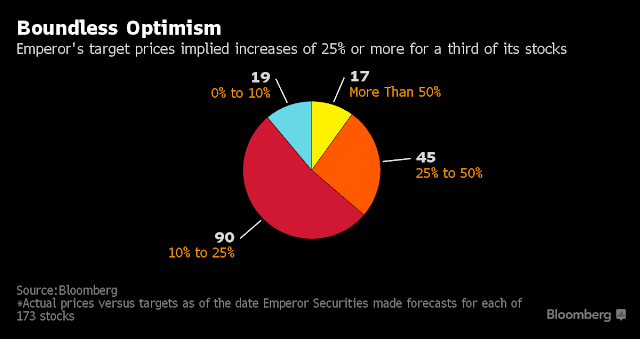

The unit of Emperor Capital Group Ltd. issued buy recommendations on every one of the 173 companies it reported covering from April 2015 through May 16. Its target prices, which the company says forecast trading levels within weeks, predicted gains of 25 percent on average. They are frequently the most bullish among analysts who cover the same stocks and list their calls with Bloomberg, including those based on the standard 12-month horizon.

The picks ended up being so wrong during the past year’s rout of Chinese and Hong Kong stocks that shorting every one would have resulted in gains of about 6 percent after just four weeks and almost 13 percent if all were held through last week.

Emperor’s record highlights the perils of equity trading for new retail investors flooding markets in China and Hong Kong. Individuals piled into stocks as the Shanghai Composite Index recorded one of its best rallies ever and policy makers relaxed restrictions on mainland and Hong Kong citizens trading in each other’s markets. Emperor, which caters to such traders, said its revenue increased 64 percent in the year ending March 31 thanks in part to big increases in brokerage fees and margin-lending interest payments.

Their price targets tended to be *ahem* aggressive, but every single stock went down in the end.

Emperor got paid well, but where are the customers’ yachts?

Emperor’s latest earnings statement, released May 18 for the six months ending March 31, reported another 20 percent increase in brokerage revenue from a year earlier. Revenue from margin loans and other lending rose 141 percent to HK$373 million. At the end of the period, the company was holding HK$13 billion worth of securities as collateral for margin loans.

These are the sorts of shenanigans that happen when the sell side is not held to a a fiduciary standard. I would also add that most people that I have met in the industry try to do the right thing for their clients, but the sales incentive system is designed to encourage them to cut corners. What’s more, the ones who “do the wrong thing” have in many cases gotten paid obscene bonuses for many years, sometimes decades, before reality finally caught up with them.

Finance: A force for good?

So, I ask the question: Should China try to emulate America, or should America try to emulate China? Is it too much to ask to require investment advisors to put their clients first and be held to the same standard as doctors and lawyers? Or should the US give in to the lobbyist who characterize regulators as “nuns with guns“?

Speaking at the 69th CFA Institute Annual Conference, psychologist Daniel Goleman stated that he believes that the investment industry has a long-term problem with trust. Instead of railing about excessive regulation, finance can be positioned as a force for good:

Goleman noted that trust — or the lack thereof — remains a challenge for the industry. According to the 2016 Edelman Trust Barometer, financial services ranked dead last vis-à-vis other business sectors, with a 51% trust rating. While there undoubtedly remains a deficit, the good news is that public faith in financial services increased 8% since the 2012 survey. Still, more needs to be done to restore trust levels.

“Trust is an essential,” Goleman said. “Trust is actually part of the commodity that finance needs in order to operate well.”

What the financial industry needs, he added, is “a strategic pivot to look at what we’re doing in finance for society, for the greater good.”

Otherwise, we know what has happened in the Chinese markets.

I’m glad you did the right thing and the code of ethics is very important to follow!

Only finacial advisors who are on their own ror perhaps work with a small cadre of like minded competent people can think, write and recommend with onjectivity and honesty. Someone working for a large, structured instituition operates within a conflict-of-interest framework of necessity. One cannot serve 2 masters as it were with equal honesty and committment. Typically the needs of the institution must and will take priority. The stories about GS during the real estate collapse in 2008 are not abberations. They point to the core problem inherent to large scale financial instiutuions.. Regulation cannot create ethical action. Bob Millman