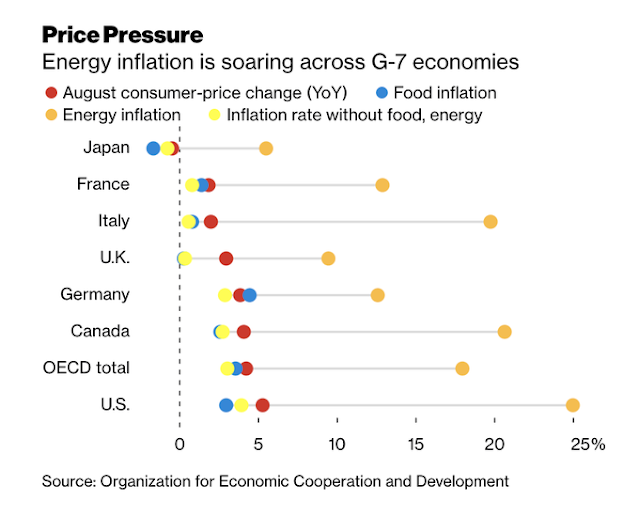

As energy prices surged around the world, I had an extensive discussion with a reader about whether the latest price spike could cause a recession. This is an important consideration for investors as recessions are equity bull market killers.

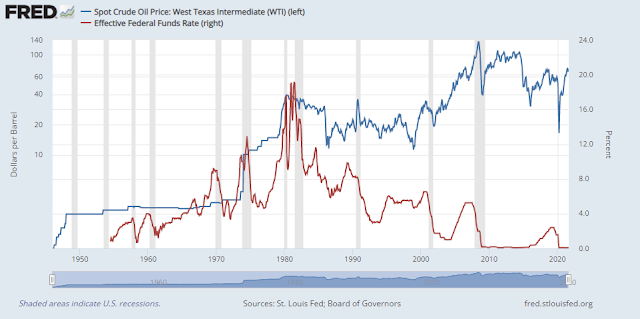

Oil shocks and recessions

This paper surveys the history of the oil industry with a particular focus on the events associated with significant changes in the price of oil. Although oil was used much differently and was substantially less important economically in the nineteenth century than it is today, there are interesting parallels between events in that era and more recent developments. Key post-World-War-II oil shocks reviewed include the Suez Crisis of 1956-57, the OPEC oil embargo of 1973-1974, the Iranian revolution of 1978-1979, the Iran-Iraq War initiated in 1980, the first Persian Gulf War in 1990-91, and the oil price spike of 2007-2008. Other more minor disturbances are also discussed, as are the economic downturns that followed each of the major postwar oil shocks.

- Arab Oil Embargo (1973-74): The Arab Oil Embargo in response to American support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War led to a supply shock and a recession.

- Iran Revolution and Iran/Iraq War (1978-81): The Iranian Revolution and subsequent war with Iraq drove oil prices up. A recession followed though the slowdown was exacerbated by the Volcker Fed’s tight monetary policy.

- First Gulf War (1990-91): Prices rose in response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. The world plunged into recession.

- Demand shock (1999-2000): Oil prices fell as low as $10 in the wake of the Asian Crisis. As demand recovered, prices surged and the price increase played a role in the subsequent recession.

- Supply shock (2007-08): Prices rose as high as $147. Hamilton argues that surging oil prices amounted to a tax on consumption and acted as a catalyst in bursting the property bubble which led to the GFC.

But then again, maybe what happened to oil prices had something to do with credit markets seizing up. The housing bubble saw people of lesser means traveling further afield to buy homes. That gave them long commutes that they were able to afford when gas was $2 a gallon, but maybe they couldn’t at $3. Housing in the exurbs got hit hardest, and one reason why is that high gasoline prices made it hard for people to lived in them to keep up with their mortgage payments, and hard for them to sell their homes without taking a steep loss. In some meaningful way, that has to have contributed to mortgage problems.

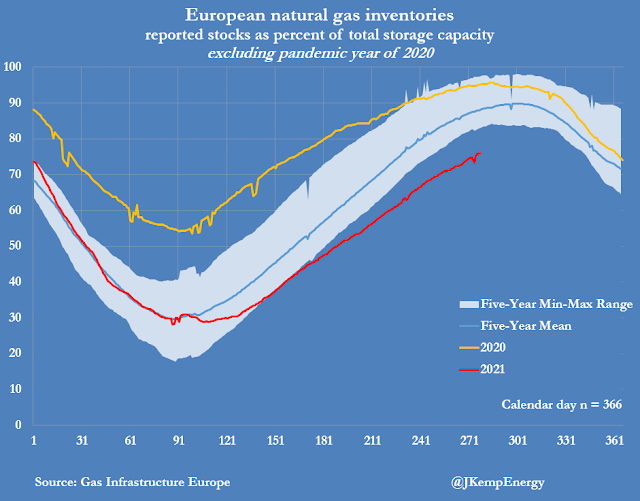

On Thursday, the Japan-Korea Marker, North Asia’s benchmark for spot liquefied natural gas shipments, surged to $34.47 per million British thermal units, the highest on records going back to 2009, according to price reporting agency S&P Global Platts. Converting that into oil units, also gives a price of about $190 per barrel of oil equivalent.

Exploring cause and effect

We quantify the conditional recessionary effect of oil price shocks in the net oil price increase model for all episodes of net oil price increases since the mid-1970s. Compared to the linear model, the cumulative effect of oil price shocks over the course of the next two years is much larger in the net oil price increase model. For example, oil price shocks explain a 3 percent cumulative reduction in U.S. real GDP in the late 1970s and early 1980s and a 5 percent cumulative reduction during the financial crisis.

There was, however, an important caveat to the nonlinear model [emphasis added].

Our findings are that by no means all net oil price increases in our sample appear to have been followed by recessions. The lack of a mechanical relationship between net oil price increases and recessions is consistent with the hypothesis that the recessionary effects of oil price shocks are time-varying.

In other words, recessions don’t always follow oil shocks in the nonlinear model. It depends. On the other hand, the oil shock effects on growth are very modest, which leads to the conclusion that oil prices don’t matter very much in the causation of recessions.

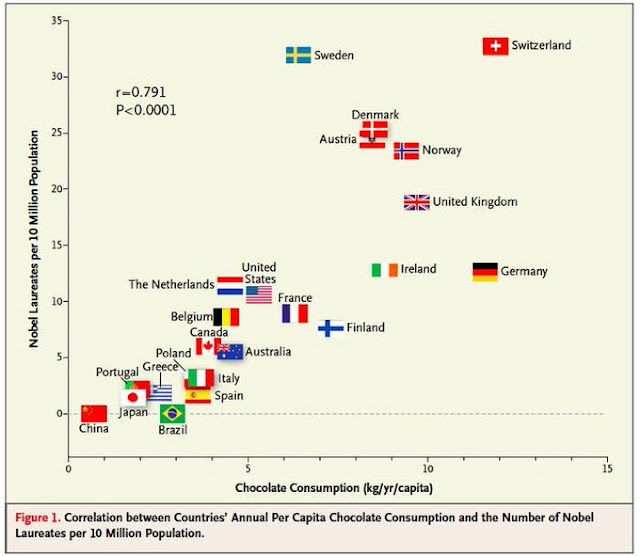

Correlation isn’t causation. Otherwise, governments would be encouraging the consumption of chocolate to win more Nobel Prizes.

A 1997 paper by Bernanke, Gertler, and Watson, “Systematic Monetary Policy and the Effects of Oil Price Shocks”, came to a similar conclusion. Bernanke et al noted that oil shock recessions were accompanied by rising interest rates. They went on to ask the question, “Is it the oil shock or the rising rates that caused the subsequent recession?” The answer turns out to be monetary policy played a much bigger role.

We find that the endogenous monetary policy response can account for a very substantial portion (in some cases, nearly all) of the depressing effects of oil price shocks on the real economy. This result is reinforced by a more disaggregated analysis, which compares the effects of oil price and monetary policy shocks on components of GDP. Looking more specifically at individual recessionary episodes associated with oil price shocks, we find that both monetary policy and other nonmoney, nonoil disturbances played important roles, but that oil shocks, per se, were not a major cause of these downturns.

Energy transition = Price volatility

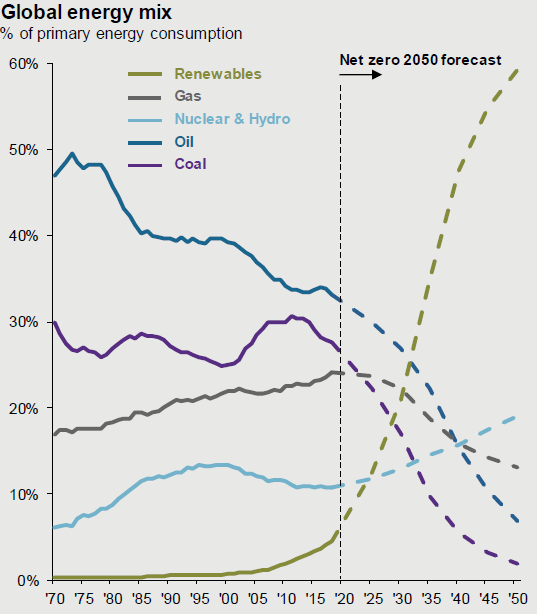

The current surge in prices is attributable to a transition to clean power. While the global economy has dealt with supply squeezes and volatile energy prices in the past, the transition process has exacerbated volatility, which is here to stay over the next decade. Policymakers have discovered the fragility of renewable power. The sun doesn’t always shine. The wind doesn’t always blow. The rain doesn’t always fall. Storage is an issue and so is power grid capacity. Price shocks, both up and down, will be inevitable during the adjustment process.

Recession ahead?

Does that mean there is an energy-induced recession in the near future? It’s unlikely.

The Bernanke paper examined the link between oil shocks and monetary policy and concluded that monetary policy dominated the recession causation. Fed policy remains accommodative and so is fiscal policy.

James Hamilton has argued that rising gasoline prices act as a tax for consumers, and the increase at the pump may have pushed an already fragile economy into recession in 2008. Today, household balance sheets are strong. While higher energy prices could slow consumer spending, they are unlikely to push the economy into recession.

Investment implications

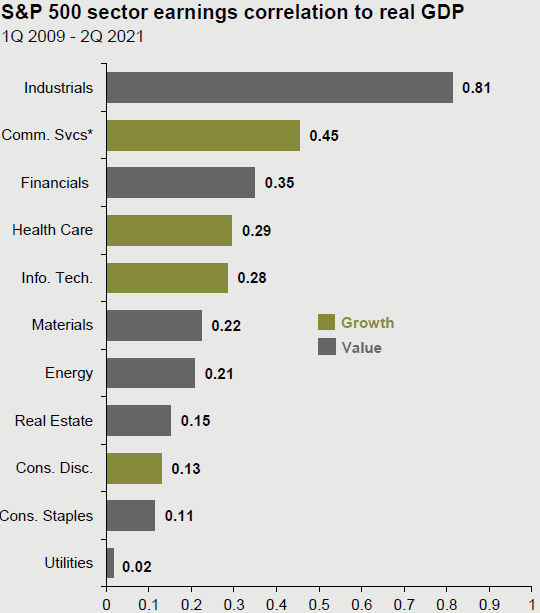

In conclusion, rising energy prices are unlikely to cause a recession in the near future, though they may act as a brake on consumer spending. The global economy is the process of normalizing after a sudden shock. Fiscal and monetary policy are easy and supportive. Investors should position themselves for the upcoming growth phase by overweighting cyclically sensitive stocks in the portfolio.

The accompanying chart shows sector earnings sensitivity to real GDP growth. Two of the top three sectors are classified as value and one, communication services, is growth. However, the recent Facebook whistleblower revelations leave the communication services sector vulnerable to antitrust regulation and oversight risk.

This analysis wouldn’t be complete with some final words about energy stocks. The energy sector has a number of attractive contrarian characteristics. The clean energy transition has made the sector the new tobacco. Companies are reluctant to invest significantly in capex in light of net-zero initiatives, which is reducing production capacity as cyclical demand rises during the economic recovery. As an example, coal stocks, which is the dirtiest of energy sources, have soared.

In the short term, oil and gas stocks are highly extended and testing both absolute resistance and relative resistance. While this sector is attractive from a macro viewpoint over the next few years, investors are advised to wait for a pullback before committing funds to these stocks.

My vote for best newsletter of the year.

I see evidence of straining and surging ETF sectors due to higher oil and natural gas prices in my momentum work.

Europe, Japan, Korea and other net importers are lagging. Canada and Australia are strong.

The Friday monthly jobs number for Canada was incredible, up 157,000. To compare to America multiply by 10. Imagine if America posted 1.57 million net new jobs. Canada has now regain ALL pandemic lost jobs. No wonder the Loonie surged. I expect a long run of Canadian market outperformance.

If you are a cyclical and commodity bull in Canada, you need to hedge out your CAD exposure.

I think that this is looking for causation when really it is the other way around. How often do oil prices go up in a recession? Are they not lower by the end of the recession? So I would expect them to be higher before the recession than just after. Ultimately though the cost of production of tangible goods is influenced by the price of energy, and the efficiency of the energy usage.

James Hamilton’s work indicates that surging energy prices act as a tax on consumers and act as a recession catalyst. In addition, the Fed reacts to the inflationary pressures from the feed-through of higher energy prices and tightens.

This time, US household finances are in strong shape. Unlikely to cause recession though rising energy could slow growth.

Interesting take by John Dizard.

https://www.ft.com/content/6478625f-1d62-4bd0-8a27-5ee3de6f36bc#comments-anchor

He thinks the consumers and probably businesses over-ordered goods in 2020-21, and therefore will not need to re-order them in near future (2022?) again.

That may cause recession (in 2022?)!

I assume he meant durable goods.

Not a surprise. See the beer distribution game played with first year MIT MBA students.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-10-07/beer-distribution-game-mit-sloan-students-learn-about-supply-chain

(Special trick to read most Bloomberg articles if you’re not a subscriber: Open the link in an incognito window.)