For the longest time, I never “got” crytocurrencies. I never bought into the idea of an urgent need for a currency that is outside the control of the “authorities”, or how you ascribe value to something that had no cash flow. If it has no cash flow, then how do you calculate a DCF value? Here is the perspective from Morningstar:

As with copper ingots, seashells, peacock feathers, and gold before it, cryptocurrency is a medium of exchange, rather than something that creates wealth on its own. It can be used to purchase cash–but it does not earn it. Try as you wish, your bitcoin receipt won’t trigger dividend checks, any more than will a sheaf of peacock feathers or a mountain’s worth of copper.

Assessing cryptocurrencies by calculating the value of their future payments is therefore a dead end. If cyber coins can be appraised, even tentatively, another approach must be found.

That cryptocurrencies do not generate cash does not mean that they lack worth. Seashells and peacock feathers don’t go very far these days, but throughout history and across societies, gold has reliably been prized. So, too, have been rare gems.

How do you keep it safe? One of the functions of a bank, which exists within the formal financial system, is to keep you money safer than stuffing it under the mattress. Banks are there to mitigate situations of the apocryphal story of the Bitcoin pioneer who put a token $100 into BTC during its early days. Several years later, he realized he was a millionaire but he lost his password.

This also brings up the issue of the role of money and banking in managing a medium of exchange that functions as a store of value.

Money and banking

Notwithstanding the stories of how crypto-exchanges have been hacked and drained of their holdings, the existence of the cryptocurrency ecosystem brings up a crucial question of money and banking. How do you lend out a cryptocurrency? What is the interest rate, and what are the mechanisms for determining the correct rate, as well as the yield curve?

If there is a financial intermediary standing between cryptocurrency users in order to facilitate lending, such as a bank or an exchange, how do you deal with reserve requirements, and the issues that arise from a fractional banking system?

These issues can’t be just swept under the rug. Money lenders have existed throughout human history. There is the Biblical story of Christ and the money lenders in the Temple. The Koran specifies prohibitions against lending, which spawned the industry of Islamic finance.

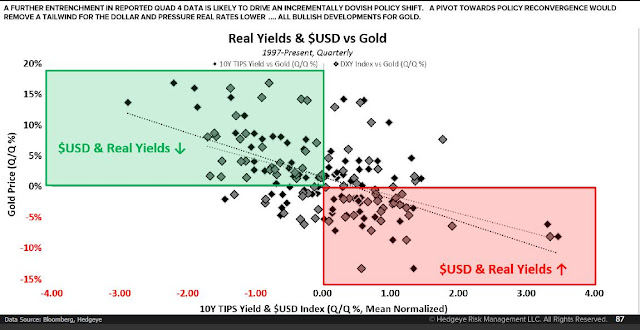

Consider gold, which is a recognized store of value in many quarters. The historical experience shows an inverse relationship between real interest rates and the price of gold.

Banking matters. Interest rates matter.

The Epiphany

My epiphany came from an article in FT Alphaville. The fact that cryptocurrencies have no cash flow is a feature, not a bug:

Last week, Martin Walker came up with an elegant way of thinking about them: as zero coupon perpetual bonds — something that pays no return, and never gets repaid. This is a sophisticated kind of nothingness, in the financial sense.

Cryptos may be based on nothingness, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that they’re worthless. In fact, the value they provide might depend upon them being linked to nothing, rather than something. This is a kind of security that crops up very rarely, like precious metals, or great works of art.

I had been thinking about cryptocurrencies in the wrong way. Traditional financial vehicles, like stocks and bonds, can be calculated with DCF models using cash flow estimates. They are therefore “concstrained” in their valuation.

Financial securities have constraints that can be used to model their risk and define their value. Bonds are issued by highly trusted borrowers, and provide predictable cash flows and specified dates of maturity, when they are converted into money. Equities provide less predictable cash flows, in the form of dividends, that come at the discretion of company managers. In the case of currencies, the value is realised through buying goods or services – a role that cryptocurrencies have yet to properly assume.

In each of those cases, the value of the security is partly constrained by these realities, despite the psychological volatility of the markets where they are traded. Very risky equities might provide very high returns, but there is still something that anchors their worth – usually a particular business proposition. Bonds will very rarely provide high returns, unless they are bought at distressed values. Currencies that actually work as currencies are anchored to their own purchasing power measured against a collective basket of goods and services available in an economy, which is why they have no value on a desert island.

By contrast, BTC and other crytocurrencies have unconstrained value.

In the case of something like bitcoin, there is basically no anchor. There are no discounted cash flow models, or estimated valuations in Chapter 11. If such things existed, bitcoin would be a far less effective medium for speculation. In its current form, it is a rare example of an unconstrained security, valued as a pure projection of psychological volatility in a secondary market. Such things are usually referred to as “bubbles”, but they can offer a perverse kind of value.

Why would you want to invest in something that is unconstrained? The answer is that sometimes asymmetrical utility can be derived from large windfalls. If you have a small amount of initial capital, you might take on a less favourable risk-reward profile for a shot at a higher nominal windfall that is unachievable elsewhere. The classic example of this is the lottery (which former Alphavillian Kadhim Shubber compared to bitcoin here, in relation to its entertainment value). Extreme returns are possible in unconstrained securities because there is no basis for their value in the first place. The upper bound is some unknown quantification of psychological appetite for speculation.

In essence, they take on the characteristics of a lottery ticket:

Now let’s consider the psychology. Demand for cryptocurrencies is very high in urban centres where young people, mostly disengaged from other financial securities, are plagued by monthly cash-flow problems (often caused by high living costs). These individuals have tendencies to blow small windfalls on luxuries, like holidays.

If they invest £200 in equities, the annual dividend returns are obliterated by their daily cash flows in a modern city. If they make £800 on that investment, they are liable to spend the proceeds, because the amount feels so distant from the lower boundary of urban residential real estate prices. This has little to do with discipline; it is better explained by the relative pricing of daily living costs, meaningful assets, and salaries.

Individuals in these situations may prefer to speculate on nothingness, hoping their peers transfer wealth to them, than plough into markets for established securities, where the risk-reward profile is better but the upper limit on returns is nominally minuscule. This also explains why, often, they are more attracted to equities that look like zero coupon perpetual bonds (certain tech companies), which are similar to unconstrained securities, except that management can extract the proceeds.

A real life example

Years ago, when I lived in Boston, and later in the Connecticut, my wife and I used to take weekend trips into New York City for the art auction previews at Christie’s and Sotheby’s. It was a cheap excursion, and it was a free way to see high-end art before they disappeared into someone’s private collection.

I can recall one specific incident when we were at an Impressionist preview. We came upon a small Renoir portrait of a young girl, and the auction estimate was $2-3 million. The picture was stunning, and bore the classic brushstrokes of Pierre Auguste Renoir (similar image below). My wife turned to me and said, “I don’t like being poor!”

Notwithstanding the fact that we could barely afford to insure such a painting, this begs the question, “Why is the painting by a well-recognized artist such as Renoir or Rembrandt worth millions? How is it different from the pictures painted by millions of children that wind up on their parents’ fridge doors?”

Works of art don’t generate any cash flow, if at all. An owner could sell tickets for people to see a painting, but the DCF value of the exhibit, after the rental of the space, security costs, and so on, is not going to be anywhere near the price paid for the art.

The answer is the speculative value of the art, or the crytocurrency, as they have “unconstrained” value. On the other hand, the value of art, just like seashells as stores of value, rise and fall based on their fashion. You can buy the work of an up-and-coming artist and see it soar in value several year later, purchase the work of a recognized artist like Renoir or Rembrandt in the expectation that it will hold its value, or see the artist’s work go out of fashion and depreciate to the value of a child’s drawing on a refrigerator.

Here’s why everyone should own bitcoin:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g-zIbVEjVpQ

hillarious

I think the value of cryptocurrencies is set by the market. They have no intrinsic value. But there is nothing special about them, they are not unique, there are over 1000 of them. Fads change, what happens when another crypto becomes more popular because it is faster, easier, cheaper to mine, converts easily into other cryptos? One thing I think that all will agree on is that evolution in the technological space is rapid. Netflix could never get started today mailing dvds when one can stream videos, so I doubt that bitcoin will stay the best crypto on the block for decades. Once it falls out of favor, who will want it? It has no intrinsic value. So if I were to invest in cryptos, I would look at the newer ones and see if there was one that I thought might even one day replace bitcoin. What will happen when it costs more electricity to mine the coins than the coins gained in mining? Who will mine them at a loss?

‘Speculating’ is more appropriate than ‘investing’ in crypto or ‘unconstrained value’.

Just like art, collectables, its value is reflected by the rarity, what the next buyer is willing to pay and liquidity in the monetary system. What Crypto lacks is the limited supply inspite of what many said about finite quantity.

If I remember correctly blockchain can be used by the government to create their own cryptocurrency and one that does not have open ledger while giving them an unprecedented level of oversight and hence control over their currency. Again have to double check on this. I’m not touching any bitcoin that can be regulated out of existence.