Last week, Donald Trump tweeted his dissatisfaction with General Motors’ decision to close four US plants.

I feel his pain. Indeed, wage growth in Old Economy industries have been stagnant for quite some time.

The WSJ wrote an editorial in response:

President Trump believes he can command markets like King Canute thought he could the tides. But General Motors has again exposed the inability of any politician to arrest the changes in technology and consumer tastes roiling the auto industry.

I agree. Trump’s 1950’s framework for analyzing the economy has become outdated. The world is moving on, and investors should move on too.

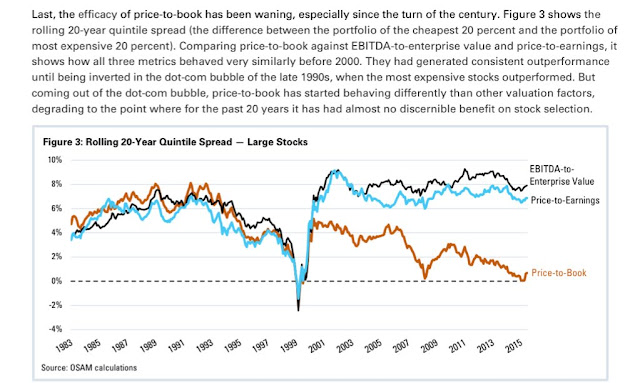

The death of P/B

Notwithstanding the pros and cons of the decisions of GM management, here is the message from the market. Jim O’Shaughnessy of O’Shaughness Asset Management highlighted the long-term return differential between the Price to Book factor (red line) and other cash flow factors. Simply put, P/B doesn’t work anymore as a stock selection technique anymore.

In the days of our parents and grandparents, investors analyzed companies based on the returns of corporate assets, and how hard management sweated those assets. Those days of companies of using the classic economic inputs of capital, labor, and rents (land) is becoming obsolete, as evidenced by the failure of the P/B factor in stock selection.

Here is how the Morgan Stanley auto analyst reacted to the GM decision:

The next morning, as we hosted joint investor meetings with HK-based clients with my European colleague Harald Hendrikse, we agreed that GM management has accomplished something truly unprecedented: elimination of significant excess capacity from a position of strength before the market downturn. We also agreed that the read-across to the global auto sector is highly significant.

He concluded:

GM is conducting a masterclass in how to manage a portfolio of increasingly obsolete businesses. Mary Barra’s leadership strength and strategic acumen are proving to be a valuable asset to shareholders. The GM team’s combination of awareness and action (vision and execution) is an example for OEMs globally that must guide these extremely large, complex, and frequently culturally entrenched organizations into new markets while dismantling parts of the business with potentially negative terminal values.

The world has changed, and building plants that employ production workers may not be the best way to compete for many companies in today’s economy.

Buffett’s pivot

As another example of how the world is changing, consider Warren Buffett, the legendary investor who spent a lifetime profiting from buying dull little businesses at reasonable prices. Adam Seessel explained in a recent Fortune article how Buffett has changed his stripes [emphasis added]:

Buffett began his career nearly 70 years ago by investing in drab, beaten-up companies trading for less than the liquidation value of their assets—that’s how he came to own Berkshire Hathaway, a rundown New England textile mill that became the platform for his investment empire. Buffett later shifted his focus to branded companies that could earn good returns and also to insurance companies, which were boring but generated lots of cash he could reinvest. Consumer products giants like Coca-Cola, insurers like Geico—reliable, knowable, and familiar—that’s what Buffett has favored for decades, and that’s what for decades his followers have too.

Now, in front of roughly 40,000 shareholders and fans, he was intimating that we should become familiar with a new reality: The world was changing, and the tech companies that value investors used to haughtily dismiss were here to stay—and were immensely valuable.

“The four largest companies today by market value do not need any net tangible assets,” he said. “They are not like AT&T, GM, or Exxon Mobil, requiring lots of capital to produce earnings. We have become an asset-light economy.” Buffett went on to say that Berkshire had erred by not buying Alphabet, parent of Google. He also discussed his position in Apple, which he began buying in early 2016. At roughly $50 billion, that Apple stake represents Buffett’s single largest holding—by a factor of two.

At the cocktail parties afterward, however, all the talk I heard was about insurance companies—traditional value plays, and the very kind of mature, capital-intensive businesses that Buffett had just said were receding in the rearview mirror. As a professional money manager and a Berkshire shareholder myself, it struck me: Had anyone heard their guru suggesting that they look forward rather than behind?

Buffett and his partner Charlie Munger became wildly successful by buying good companies with “moats”, or strong competitive positions, at reasonable prices. He avoided technology companies because he believed that their competitive moat were, at best, fleeting:

With the help of his partner Charlie Munger, Buffett studied and came to deeply understand this ecosystem—for that’s what it was, an ecosystem, even though there was no such term at the time. Over the next several decades, he and Munger engaged in a series of lucrative investments in branded companies and the television networks and advertising agencies that enabled them. While Graham’s cigar-butt investing remained a staple of his trade, Buffett understood that the big money lay elsewhere. As he wrote in 1967, “Although I consider myself to be primarily in the quantitative school, the really sensational ideas I have had over the years have been heavily weighted toward the qualitative side, where I have had a ‘high-probability insight.’ This is what causes the cash register to really sing.”

Thus was born what Chris Begg, CEO of Essex, Mass., money manager East Coast Asset Management, calls Value 2.0: finding a superior business and paying a reasonable price for it. The margin of safety lies not in the tangible assets but rather in the sustainability of the business itself. Key to this was the “high-probability insight”—that the company was so dominant, its future so stable, that the multiple one paid in terms of current earnings would not only hold but perhaps also expand. Revolutionary though the insight was at the time, to Buffett this was just math: The more assured the profits in the future, the higher the price you could pay today.

This explains why for decades Buffett avoided technology stocks. There was growth in tech, for sure, but there was little certainty. Things changed too quickly; every boom was accompanied by a bust. In the midst of such flux, who could find a high-probability insight? “I know as much about semiconductors or integrated circuits as I do of the mating habits of the chrzaszcz,” Buffett wrote in 1967, referring to an obscure Polish beetle. Thirty years later, writing to a friend who recommended that he look at Microsoft, Buffett said that while it appeared the company had a long runway of protected growth, “to calibrate whether my certainty is 80% or 55% … for a 20-year run would be folly.”

Here is how Buffett changed his mind on Apple, the platform company, which now comprises about one-quarter of Berkshire’s portfolio:

Now, however, Apple is Buffett’s largest investment. Indeed, it’s more than double the value of his No. 2 holding, old-economy stalwart Bank of America.

Why? Not because Buffett has changed. The world has.

And quite suddenly: Ten years ago, the top four companies in the world by market capitalization were Exxon Mobil, PetroChina, General Electric, and Gazprom—three energy companies and an industrial conglomerate. Now they are all “tech”—Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, and Alphabet—but not in the same way that semiconductors and integrated circuits are tech. These businesses, in fact, have much more in common with the durable, dominant consumer franchises of the postwar period. Their products and services are woven into the everyday fabric of the lives of billions of people. Thanks to daily usage and good, old-fashioned human habit, this interweaving will only deepen with the passage of time.

Explaining his Apple investment to CNBC, Buffett recalled making such a connection while taking his great-grandchildren and their friends to Dairy Queen; they were so immersed in their iPhones that it was difficult to find out what kind of ice cream they wanted.

“I didn’t go into Apple because it was a tech stock in the least,” Buffett said at this year’s annual meeting. “I went into Apple because … of the value of their ecosystem and how permanent that ecosystem could be.”

Buffett began to understand how platform companies like Apple, Google, and Amazon were breaching the competitive moat of the old economy companies that Berkshire once invested in:

As these platform companies create billions in value, they are simultaneously undermining the postwar ecosystem that Buffett has understood and profited from. Entire swaths of the economy are now at risk, and investors would do well not only to consider Value 3.0 prospectively but also to give some thought to what might be vulnerable in their Value 2.0 portfolios.

Some of these risks, such as those facing retail, are obvious (RIP, Sears). More important, what might be called the Media-Consumer Products Industrial Complex is slowly but surely withering away. As recently as 20 years ago, big brands could use network television to reach millions of Americans who tuned in simultaneously to watch shows like Friends and Home Improvement. Then came specialized cable networks, which turned broadcasting into narrowcasting. Now Google and Facebook can target advertising to a single individual, which means that in a little more than a generation we have gone from broadcasting to narrowcasting to mono-casting.

As a result, the network effects of the TV ecosystem are largely defunct. This has dangerous implications not only for legacy media companies but also for all the brands that thrived in it. Millennials, now the largest demographic in the U.S., are tuning out both ad-based television and megabrands. Johnson & Johnson’s baby products, for example, including its iconic No More Tears shampoo, have lost more than 10 points of market share in the last five years—an astonishingly sharp shift in a once terrarium-like category. Meanwhile, Amazon and other Internet retailers have introduced price transparency and frictionless choice. Americans are also becoming more health conscious and more locally oriented, trends that favor niche brands. Even Narragansett beer is making a comeback. With volume growth, pricing power, and, above all, the hold these brands once had on us all in doubt, it’s appropriate to ask: What’s the fair price for a consumer “franchise”?

Investors like O’Shaughnessy understand how the world is changing. So does Warren Buffett. Does Trump understand the key drivers of a long-term sustainable competitive advantage, or will he continue to look in the rear-view mirror and focus on the old economic models?

For the last word, I conclude with the WSJ editorial from last Wednesday:

Mr. Trump and Democrats seem to believe that with the right mix of tariffs and managed trade they can return to a U.S. economy built on steel and autos. This is the logic behind the Administration stipulating in its new trade agreement with Mexico and Canada that 40% to 45% of a vehicle’s value must consist of parts made by workers earning at least $16 an hour.

But an economy doesn’t run on nostalgia. U.S. auto makers don’t fear the new wage mandate because engineering performed by higher-skilled U.S. employees accounts for ever-more of a vehicle’s value. GM could soon become as much a tech company as a manufacturer. Amid a strong economy, most laid-off GM employees should find work. GM may also decide to retool idled factories to produce trucks as Fiat Chrysler has with a plant in Michigan.

Old Economy, meet the New Economy.

Thanks Cam, I strongly agree. On the other hand the US may retain its leadership for a while. Europe has a very tech unfriendly political environment has a shortage of programmers and is still losing a lot of its top talent to US companies and universities. China and India could compete with the US based on the number of software developers for instance, but China just recently told its internet companies that they were collecting too much data (government wants to keep its information monopoly) and the majority of India’s developers are working for foreign companies (either directly or indirectly)

The issue I am raising isn’t about leadership, which I will deal with in a future discussion. The issue is Old vs. New Economy companies and the analytical framework you should use to analyze them.

In other news there is talk about Ford being next to announce major layoffs:

https://t.co/NJmIlF9d2x

I’m sorry but I beg to differ on the long term analysis of a changing economy. A funny thing happened on the way to this “changing economy.” I still go to Amazon and my local stores and buy hard goods. I haven’t changed in that regard and neither has the rest of the world.

What has changed is wage disparity between countries. The reason most of the hard goods we buy are made in other, developing, countries is the result of wage disparity. Manufacturing wages in the West are much, much higher than in China and other developing countries. This will NOT be the case forever. Wages are already climbing in China and will eventually close in on parity.

And then there is the cost of transportation of goods half way around the world. Cheap oil has further facilitated this disparity in goods manufacture. But, oil isn’t going to be $50 a barrel forever. $200 oil is probably somewhere in our future. Do we have an energy source to replace oil? No. Not even at higher prices.

And a third disparity in the equation is the fact that China steal technology, ignores patents and doesn’t play by the rules. They are also abusing tariffs to their advantage. This too will not go on forever.

Trump is on the right track. Remove the disparities that he can, notably those in the previous paragraph and begin to bring manufacturing back to America. While we are still at somewhat of a disadvantage with regard to wages, that disparity and others will disappear over time. We should be preparing and striving to keep the roots of manufacturing in the U.S. This isn’t “old economics,” it’s FUTURE economics.

It seems too many economists can’t see the forest for the trees.

I understand your visceral reaction, but this is not about what is right or wrong, about what is just, but about how to make money. Both the quantitative evidence and the behavioral pattern of smart investors like Buffett indicates that the world has changed, and investors should change with it.

The title of the article says it all. Say good bye to 1950s (American manufacturing).

Tesla epitomizes what Cam is saying perfectly as an example. Tesla owners love it for the ease of car updates, based on software. As improvements in Tesla come forth, it is “beam me up scottie” via the airwaves. Yes, Marc Andreessen was right, “software is eating the world”. The future is not in making cars the way we did in 1950s but the way Tesla has shown. A hardware, that updates itself on the airwaves.

Why did I fire Microsoft from my life and buy Apple? Because, Apple delivers hardware, that maintains itself (no wonder Mr. Buffet bought boat loads of Apple). Microsoft, on the other hand, was demanding more of my time to just maintain its software and the hardware, literally broke off its hinges!

So, analog systems (like celluloid movies and polaroid pictures) got killed by digital imaging. X ray films and film makers like Kodak got killed. Analog audio got demolished by digital. Money, soon, will become digital, it is a matter of time. Soon, dumb TVs will be forced to be smart, someone will figure it out.

Purchases on Amazon are being made with the least amount of human intervention.

In the same vein, I do not understand why cashiers at McDonald’s exist or for that matter why McDonald’s needs humans to take orders, when software can do the job. Furthermore, I also do not completely understand why humans are required to fry potato fries at McDonalds instead of mechanizing the task.

I quote from the above:

“Does Trump understand the key drivers of a long-term sustainable competitive advantage, or will he continue to look in the rear-view mirror and focus on the old economic models?”

The answer to the above is a firm no. Our president, IMHO opinion does not understand this idea. Yes, fair trade is all fine and all that, but using tariffs is a blunt instrument, as we are watching in front of our eyes. Negotiating with China is not exactly negotiating with a supplier of bathroom and other fixtures for Trump tower, now is it?

There is more to the story with J&J’s “No more tears” shampoos an example. Like J&J, Proctor and Gamble is likely going to come under fire for its premium products. L Brands and Hanes brands have both experienced powerful deflationary forces unleashed by globalization.

President Trump wants to go back to the America, that was. However, globalization, digitization, availability of efficient networks, and robotic manufacturing is the future of America. President does not get it, with or without China.

So, with GM, let us also add the example of another iconic American company GE. America bailed out GM, and GM is now struggling to retool itself. Mismanagement has brought GE to its knees. It cut its dividend to raise cash on its books. How shameful. These are examples of old America, old style of valuations (like P/B), simply do not work. What works in valuations is “stickiness” of the platform, like an Apple or Amazon. Even Facebook and Google IMHO are not as sticky as Apple or Amazon. Just my 2 cents. Were it not for the cash burn rate of Netflix, yes it could claim the same moat or stature as an Apple or Amazon. Netflix just sold bonds to raise cash!! Again, very “sticky” company, but not sure how it is going to survive its steep cash burn.

As an aside, ATT has 188 billion $ of debt, but has become content king. So, here is old America, that gobbled up content by buying Time Warner, and has beefed up its satellite network by gobbling up dish network a few years ago. Its arch rival, Verizon has only bandwidth, but no content. Usually bandwidth is commodity, so it will be interesting to see if another Old American company called ATT is able to make a successful transition to a new business model or gets crushed under the weight of its debt (like GE).

So, the future as Tom Friedman said in his book “The world is flat” is “Cheaper, faster and better”. You, the reader should decide if America is moving to “Cheaper, faster, better” or the opposite, under our current President.

I believe intelligence is an irresistible force..dna is intelligence, so is a bacteria that can move. Intelligence has the odds favoring it. Now is it intelligent to make things more expensive to make? After all, the expense is in a sense related to energy. We only have so much. If phones or TVs or clothes cost more, then we buy less units. Machines, houses, you name it they will all get smarter, and the process will accelerate. This is beyond any politician.

As we can see here with intelligent people debating these important issues, this is a complex subject. We are seeing in politics around the world, elections of populist governments both far right and left that offer simple solutions that seem right to voters but aren’t backed by science or learned experts.

Successful democracies have historically had a method of vetting potential leaders before elections. Potential leaders who appreciated knowledge as opposed to personal hunches. This has changed and not just in America. But of course America is the big fish in the pond. As Michael Lewis’s new book outlines, important agencies of the government are seeing highly qualified experts heading them being fired and amateurs appointed to take over to promote populist ideas. The damage will be huge.

Unsuccessful populist governments either elected or put in place by revolution fail because they make economic policies that seem good for the populace but unfortunately don’t work. Then as their economy spirals down, they blame others for their plight.

The social upheaval coming with technology will challenge the smartest minds. Fostering a greater emotional divide between winners and losers as all populists do, is exactly the wrong approach. It will lead to ……… (add your word here)

re: ‘I conclude with the WSJ editorial from last Wednesday: ‘Mr. Trump and Democrats seem to believe that with the right mix of tariffs’ ‘

A new Quinnipiac University poll found that most Democrats oppose the tariffs and don’t approve of Trump’s handling of trade policy.

Seventy-three percent of Democrats oppose the steel and aluminum tariffs, compared to 20 percent of Republicans and 55 percent of Independents, according to the poll.

Cam, great call on the fade the Trump trade talk rally! I was thinking of waiting before fading this rally but your call and the Dow Jones Transport (-2.7% so far) relative strength to Dow yesterday afternoon and this morning suggested otherwise.

wow.

73% of democrats are against their #1 political belief: taxing the people ever more to support an ever expanding government. Buffett is a genius for buying apple 5 yrs after Jobs death, and they haven’t had a solid idea since his death. It’s no longer significant to consider value in investing.

Ok, that’s it, I’m stopping my subscription to the comedy channel, you guys have got it covered.

Exacta buy signal today Cam. Does that change your inner trader’s short-term outlook?

Signal is highly marginal. TRIN very high, but VIX term structure only inverted if you round to 2 decimal places. We need more panic.

So far, no panic sell off, like 1000 point drop in Dow over a day or 9 to 1 down to up volume. Spot VIX remains only at 20.xy. Would like to see spot VIX close to 30 or above. See the possible road map to retest 2600;

https://twitter.com/ukarlewitz/status/1070110262739390465

Last time we tested the 2600 level was on 11-26-2018. Another tweet or two from the president will get you there or below and that would be a better entry point on the long side of the ledger.

So what is wrong with this picture? A black swan event like the President getting mired in litigation, Watergate style, possible after 1 January, as the House turns democrat.