The announcement was not totally unexpected, according to the BBC, but it did come as a shock. China’s Communist Party announced the Central Committee proposed that the term of the President and Vice President may serve beyond their 10-year terms:

The Communist Party of China Central Committee proposed to remove the expression that the President and Vice-President of the People’s Republic of China “shall serve no more than two consecutive terms” from the country’s Constitution.

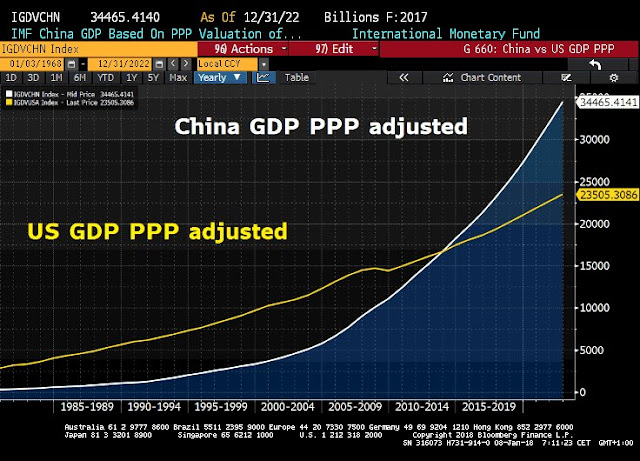

The announcement prompted both bullish and bearish reactions. China bulls warmed to the prospect of stability and predictability in the Chinese leadership and highlighted this chart. China is likely to continue on its steady growth path.

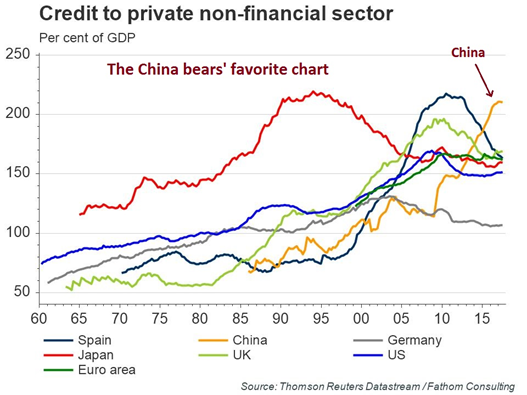

China bears pointed to the rising risks in the country’s growing debt load, which is already at nosebleed levels.

Virtually everyone on social media embraced this interpretation of Xi as the next emperor, or compared him to Mao Zedong.

How should investors react to this political development?

Lessons from Deng

Notwithstanding the objections over human rights violations and political repression in China, I refer readers to the opinion piece written by Bloomberg’s Tom Orlik soon after China’s 19th Party Congress. Orlik reminded us about how Deng Xiaopeng launched China on its vaunted growth path and what Xi Jinping could learn from Deng:

The first, from the early years of Deng’s leadership, is that the market is the surest path to growth. It wasn’t the government’s 10-year economic plan — with its grandiose aim to drive rapid development by importing whole industrial plants — that propelled China’s expansion. It was a grass-roots overhaul of the agricultural system that freed the industry and enterprise of hundreds of millions of farmers. For Xi, making good on commitments to give the market a “decisive role” in China’s economy will likewise be the key to sustaining growth.

A second lesson is that it’s OK to step back from unrealistic targets. The ambitions of the 10-year plan had to be scaled back when petroleum exploration failed to deliver the revenue necessary to pay for imported industrial plants…

Third, short-term costs are acceptable and inevitable…

Finally, leadership choices are critical.

In other words, trust market forces, downgrade the urge for central planning. Orlik gave the 19th Party Congress initiatives a mixed review:

The early signs on economic policy from the 19th Party Congress are mixed. On one hand, Xi dropped the explicit mention of the commitment to double GDP from 2010 to 2020 — the basis of the annual 6.5 percent growth target. If that target is now sidelined, it will remove a significant distortion from China’s policy apparatus and a major cause of rising debt levels. On the other hand, China’s state planners appear to be in the ascendant. Industrial strategy loomed large in Xi’s speech. The call for a “stronger, better, bigger” state sector was echoed.

The most worrisome is the trend away from a reliance on market forces and towards central planning by giving more power to SOEs.

Policy lessons from the Anbang debacle

If the continuation of the Xi presidency represents continuity of current policies, the case of Anbang Insurance is troubling. This Bloomberg article summarized events well:

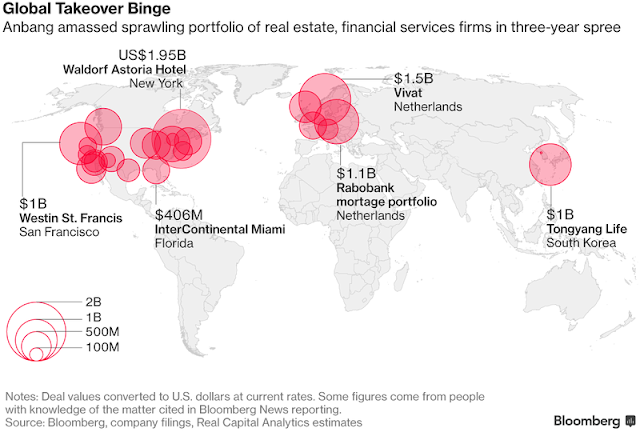

China’s government seized temporary control of Anbang Insurance Group Co. and will prosecute founder Wu Xiaohui for alleged fraud, cementing the downfall of a politically connected dealmaker whose aggressive global expansion came to symbolize the financial overreach of China’s debt-laden conglomerates.

The surprise move furthers President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption and de-leveraging campaigns while providing a government backstop for the high-yield investment products that Anbang sold to hordes of Chinese citizens. It suggests that after months of clamping down on acquisitive tycoons, China is increasingly focused on insulating the economy from their shaky finances.

It’s a remarkable turn for Anbang, which burst onto the global scene in 2014 with the purchase of New York’s Waldorf Astoria hotel and only a year ago was in talks to invest in a company owned by the family of Jared Kushner, U.S. President Donald Trump’s son-in-law and senior adviser. With 2 trillion yuan ($315 billion) of assets, Anbang represents China’s largest-ever takeover of a privately owned company.

In truth, Anbang was a bank masquerading as an insurance company. Though most of its savings products were in theory long-term, they could be redeemed within months of investing. Moreover, its operations were burdened with negative cash flows, which had to be financed by the banking system. Combine those finances with a wild overseas buying spree, something had to give. This Christopher Balding tweet illustrates the insane pace of Anbang’s growth path.

Instead of allowing market forces to be ascendant with the use of well known banking resolution solutions by splitting the company into a “good bank” and “bad bank”, the Beijing authorities resolved this problem with a bailout.

In a bailout, who pays? China bulls may answer that the government has deep pockets and can afford it. If the same events happened in America, or any Western industrialized country, would the same bulls tell the same story? In America, it would be the taxpayers who pay for the bailout. In China, it is the household sector.

Goodbye Rebalancing, Hello Middle Income Trap

To be sure, the PBoC has many ways to cushion a financial crisis, as reserve ratios remain well above GFC levels. China has the levers to avoid a catastrophic economic collapse. However, taking such steps would mean abandoning the policy of rebalancing growth towards the consumer and household sectors.

If that is the Xi Administration’s preferred policy, China can say goodbye to rebalancing, and hello to the Middle Income Trap, or Lewis turning point. I had written about the challenges that China faced with its Middle Income Trap in 2014 (see China’s inequality and growth imperative).

For those who don’t understand what a “middle-income trap” is. It is also known a a Lewis turning point when it runs out of cheap labor and growth becomes constrained because it can’t move up the value-added ladder.

I had also referred to a paper by Akio Egawa that warned about these risks facing China:

A sensitivity analysis for three Asian upper-middle-income countries(China, Malaysia and Thailand) also shows that the situation related to a middle-income trap is worse than average in China and Malaysia. These two countries, according to the result of the sensitivity analysis, should urgently improve access to secondary education and should implement income redistribution measures to develop high-tech industries, before their demographic dividends expire. Income redistribution includes the narrowing of rural urban income disparities, benefits to low-income individuals, direct income transfers, vouchers or free provision of education and health-care, and so on, but none of these are simple to implement.

In conclusion, Xi’s ascendancy to permanent leader is unlikely to have short term effects on China’s growth path. In the long run, the direction shown by his Administration suggests that China’s growth path will start stalling in the years to come.