Bloomberg reported that Donald Trump interviewed John Taylor for the position of Fed chair and “Trump gushed about Taylor after his interview”, as “Kevin Warsh has…seen his star fade within the White House”. The current list of leading candidates under consider are said to be Jerome Powell, John Taylor, Kevin Warsh, and Janet Yellen. Taylor’s rise in the candidate stakes is a bit of a surprise, as he had been regarded as a dark horse.

The question for investors is, “What would a Taylor Fed look like?”

Taylor is famous for the “Taylor Rule”, which is a rules-based method of determining the Fed Funds rate. The rules-based approach is a favorite of the Republican audit-the-Fed crowd, and therefore Taylor will have substantial support should he get nominated. The standard application of the Taylor Rule would see the Fed Funds target substantially higher than it is today.

Despite these dire projections, Matthew Boesler at Bloomberg argued that a Taylor led Fed would not be substantially different from a Yellen Fed, because Taylor would have difficulty bringing the members of the FOMC to such a hawkish tilt to monetary policy:

Resistance from the other participants on the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee, which currently numbers 16 participants, is why investors need not worry too much about Chairman Taylor leading the Fed onto a much faster rate-hike path than the three rate increases next year penciled in by officials in quarterly forecasts updated in September.

“Taylor would have a very hard time persuading the rest of the FOMC to abide by the prescriptions of his original rule,” said Roberto Perli, a partner at Cornerstone Macro LLC in Washington. “In fact, he won’t be able to persuade hardly anyone — there isn’t much sympathy in the FOMC for a policy that blindly follows rules.”

On the other hand, uber-dove Neel Kashkari of the Minneapolis Fed argued that the application of a Taylor rule would have kept millions out of work:

In December, I wrote an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal explaining that forcing the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to mechanically follow a rule, such as the Taylor rule, to set interest rates can cause tremendous harm to the economy and the American people. My staff at the Minneapolis Fed estimates that if the FOMC had followed the Taylor rule over the past five years, 2.5 million more Americans would be out of work today. That’s enough to fill the seats at all 31 NFL stadiums simultaneously, almost 6,000 more people out of work in every congressional district.

Who is right? How should we assess John Taylor as a potential Fed chair?

Interest rate policy

For investors, the market impact of a Fed chair should be evaluated on two criteria. How will the chair conduct interest rate policy under “normal” circumstances, and how would he behave under periods of stress? Note that this framework passes no judgment on whether any person has the correct approach to the conduct of monetary policy. Our only interest is the impact of policy.

John Taylor recently gave a speech at the Boston Fed defending the use of rules-based approaches to the conduct of monetary policy (see Rules Versus Discretion: Assessing the Debate Over the Conduct of Monetary Policy: Are Rules Made to be Broken? Discretion and Monetary Policy). While he was not explicitly defending the Taylor Rule for determining a Fed Fund target, it was clear that Taylor favored a rules framework for the Fed.

That said, even the Taylor Rule has several input parameters that lead to very different results, depending on the model assumptions.

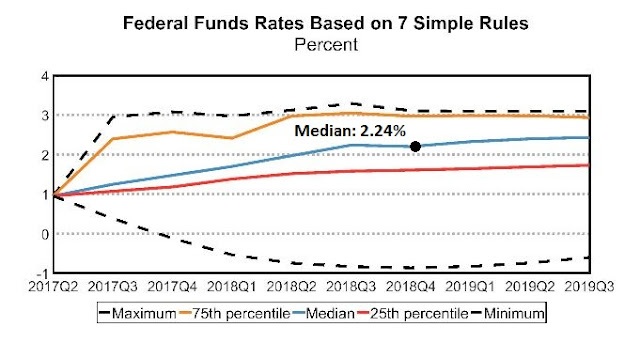

Imagine that John Taylor is the new Fed chair, and he may have some difficulty in forming a consensus on the FOMC on how quickly to normalize policy. As a way of conducting sensitivity analysis on the various models, the Cleveland Fed has a monetary policy tool that determines a Fed Funds target under different assumptions. The median Fed Funds target for December 2018 is 2.24%, which is a reasonable estimate for a compromise solution in light of the differences in opinion.

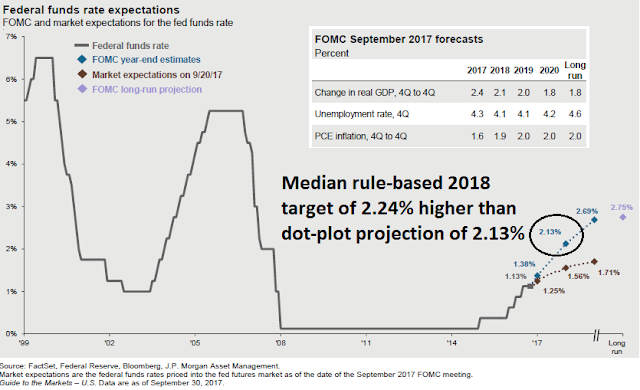

I would then point out that the median 2.24% 2018 year-end target is higher than the current dot-plot projection of 2.13%. Moreover, the current dot-plot projection is substantially higher than market based expectations for the Fed Funds rate.

That’s just the base case scenario. I pointed out in my last post (see Market melt-up and crash?) that the FOMC is likely to adopt a more hawkish tilt in 2018, irrespective of the identity of the chair. Virtually all Fed governor candidates favor rules-based approaches to monetary policy, which would put the Fed on a more hawkish path than it is today. As well, the rotation of votes among regional Fed presidents indicate a more hawkish shift, from Evans and Kashkari to Meester and Williams.

In short, the appointment of John Taylor as Fed chair is likely to see a far more hawkish Fed than under Yellen.

Crisis management

The other criteria for the evaluation of a Fed chair is how he is likely to react under stress. As interest rates have barely lifted the zero lower bound, how will the Fed behave in the next recession?

For some clues, we turn to the past writings of John Taylor. On November 15, 2010, Taylor was a signatory to the Open Letter to Ben Bernanke which urged the Fed to refrain from engaging in quantitative easing.

We believe the Federal Reserve’s large-scale asset purchase plan (so-called “quantitative easing”) should be reconsidered and discontinued. We do not believe such a plan is necessary or advisable under current circumstances. The planned asset purchases risk currency debasement and inflation, and we do not think they will achieve the Fed’s objective of promoting employment.

We subscribe to your statement in The Washington Post on November 4 that “the Federal Reserve cannot solve all the economy’s problems on its own.” In this case, we think improvements in tax, spending and regulatory policies must take precedence in a national growth program, not further monetary stimulus.

We disagree with the view that inflation needs to be pushed higher, and worry that another round of asset purchases, with interest rates still near zero over a year into the recovery, will distort financial markets and greatly complicate future Fed efforts to normalize monetary policy.

At about the same time, Taylor penned a joint opinion letter with Paul Ryan which laid the blame on the Financial Crisis on the Fed’s failure to follow a rules-based regime:

Quantitative easing is part of a recent Fed trend toward discretionary and away from rules-based monetary actions. The consequences of this trend are clear: The Fed’s decision to hold interest rates too low for too long from 2002 to 2004 exacerbated the formation of the housing bubble. And while the Fed did help to arrest the ensuing panic in the fall of 2008, its subsequent interventions have done more long-run harm than good.

QE1 failed to strengthen the economy, which has remained in a high-unemployment, low-growth slump, and there is no convincing evidence that QE2 will help either. On the contrary, QE2 will create more economic uncertainty, stemming mainly from reasonable doubts over whether the Fed will know exactly when and how to contract its balance sheet after such an unprecedented expansion.

Not only were Taylor and Ryan opposed to QE2, which was about to begin, but QE1, and interpreted QE as a way of bailing out fiscal policy:

QE1 involved the Fed in areas of fiscal policy, such as credit allocation, that are properly (and constitutionally) the domain of Congress. QE2 would double down on these expansions, as the planned purchases of Treasury securities would constitute a large fraction of soon-to-be-issued federal debt.

This looks an awful lot like an attempt to bail out fiscal policy, and such attempts call the Fed’s independence into question.

For the sake of the argument, let us assume that Taylor was correct in his assessment that the Fed’s easy monetary policy blew an asset bubble in the years leading up to the GFC, and that it fell behind the curve in its efforts to control inflationary pressures. He would be put in a similar situation today should he become the new Fed chair, as the economy is already in the late cycle phase of an expansion.

Taylor stated in a Bloomberg interview on March 27, 2017 that he believed that the Fed was behind the inflation fighting curve. A Taylor Fed would then aggressively tighten in 2018, which is likely to send the economy into a slowdown. How would he react in the downturn?

As interest rates are already relatively close to zero bound, what would a Taylor Fed do? He has stated on the record that he is opposed to unconventional monetary policy, such as QE. In that case, radical steps of helicopter money would be out of the question.

In conclusion, John Taylor nomination as a Fed chair would be a surprise, despite the reports of Trump’s gushing. While Taylor is a Republican and likely to look favorably upon financial deregulation, which is one of Trump’s priorities, a Taylor Fed would be more hawkish than the Yellen Fed and see greater economic volatility during a recession. Taylor most certainly does not fit Trump`s desire for a “low interest guy”. However, Fox Business News reported that VP Mike Pence, Heritage Foundation economist Steve Moore, conservative economist Larry Kudlow, and former Reagan adviser Arthur Laffer are involved in the search for the new chair, which could tilt the odds in Taylor’s favor.

Janet Yellen is scheduled to meet with President Trump on Thursday. Stay tuned for further developments.

Timely article, now that there is only Janet Yellen and John Taylor left in the field. Reasonable chance that John Taylor may be the next Fed chief, based on the above article.