I live in Vancouver on Canada’s west coast. This was the city I grew up in and where I chose to settle after I went into semi-retirement. It’s a great town, but property prices are sky high and have become unaffordable for many locals.

Some real estate boosters will resort to the standard explanations such as “we’ve hosted the Winter Olympics” and therefore “it’s a world class city”. But have property prices gone parabolic in other “world class city” Winter Olympics host cities like Turin, Salt Lake City, Nagano, Lillehammer, Sarajevo, or Lake Placid? I didn’t think so.

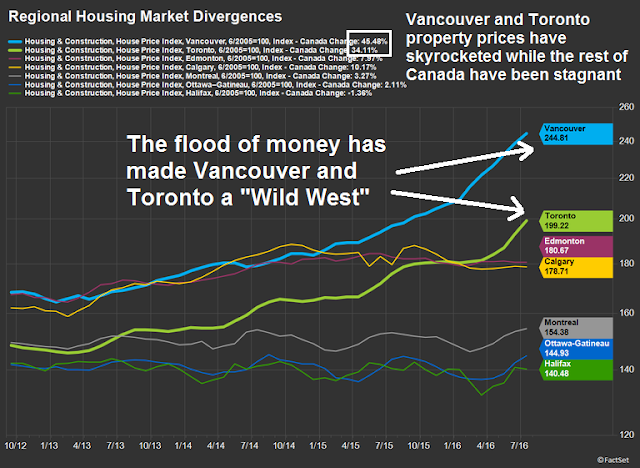

The main reason for the stratospheric prices has been called China’s Great Ball of Money and it has rolled into Canadian real estate. Factset recently documented how residential property prices have skyrocketed in Vancouver and Toronto while the rest of Canada have been flat as Mainland Chinese money has been buying in those two cities. Based on the stories that have surfaced recently, the flood of money has made the Vancouver and Toronto real estate markets a Wild West (chart annotations below are mine).

I am not here to write about how foreign money pouring into Vancouver and Toronto have caused affordability problems for local residents (true, see #HALTtheMadness on Twitter), or how Canadian authorities have turned a blind eye to the problems of money laundering and tax evasion due to offshore money flows (see this SCMP article). This is a post about vulnerabilities posed by the financial linkages between China and the rest of the world (see my previous post How much “runway” does China have left?). What happens if we see a hard landing or banking crisis in China?

Peeking under the hood of Chinese fund flows

Canada’s immigrant-investor program, which has been terminated, spawned several waves of ethnic Chinese immigration over the last few decades. The 1990’s saw emigrants come from Hong Kong and Taiwan. The latest comes from Mainland China. While there were some abuses of the program some 20 years ago, where a Canadian Revenue Agency study found a number of emigrants in luxury houses who declared “average household incomes of about C$23,000, compared to more than C$368,000 for the handful of long-term Canadian residents who bought in the same price brackets” (via SCMP article), the magnitude of the Mainland Chinese immigration today dwarfs any of the previous episodes.

A recent Globe and Mail article reported that students without income have bought CAD 57 million in Vancouver homes in the last two years. Great Ball of Money indeed!

More worrisome are the stories of the involvement of the Chinese official banking and shadow banking system to purchase real estate in Canada and elsewhere. Such arrangement create financial linkages should the Chinese economy wobble. As an example, CBC reported a case before the Canadian courts where a Chinese bank claims that a Chinese fugitive borrowed money from the bank in China and used the funds to buy several properties in the Vancouver area. He proceeded to default on the loan and then flee China.

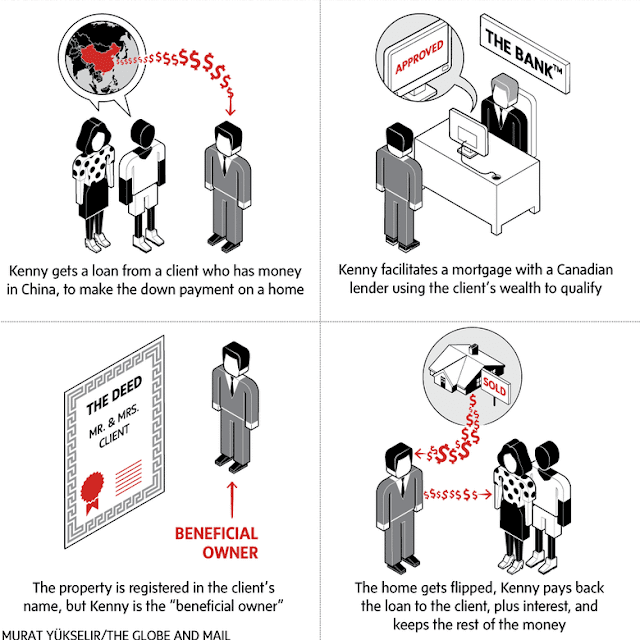

A separate article of investigative report by Canada’s Globe and Mail detailed the story of illicit Chinese money flows and how it fueled the property market boom. It documented the story of Jun Gang Gu, also known as Kenny Gu, a former civil servant originally from Nanjing, who emigrated to Canada in 2009.

Translated for The Globe, [the documents] show that Mr. Gu, or his companies, are hidden – the legal term is “beneficial” – owners of certain properties, even though absentee foreign clients bankroll everything from the down payment and mortgage payments to property-related taxes and other expenses. The homes and mortgages are registered in the names of his clients, their companies or spouses.

The financing Mr. Gu’s companies receive from those clients comes in the form of loans that are not taxable, and that fall within what’s known as “shadow banking” – an unregulated system that has exploded in popularity in China, and now appears to be getting a toehold in Canada. Such “peer-to-peer” loans, as they are also called, sidestep banks entirely, and promise lenders significantly higher returns than they can get elsewhere.

Mr. Gu’s lender clients earn their wealth primarily in China, while coming and going from Vancouver, according to Mr. Lazos. Records show that they give Mr. Gu power of attorney to facilitate everything through his small, nondescript Vancouver office, but his stake in the properties remains hidden. And although he is not licensed to broker mortgages or manage investments, records suggest he does both.

Those records also link him and his clients to activity involving at least 36 properties over the past five years. Yet Mr. Gu, 45, paid next to nothing in taxes last year, while millions of dollars flowed through his business and personal accounts.

In other words, Gu had created a network of companies that he controlled, using offshore Chinese clients as “fronts”, to buy Canadian real estate. The financing was done through China’s shadow banking system that promised investors high rates of return. In effect, this was a case of subprime lending via the Chinese shadow banking channel that fueled Gu’s real estate speculation in Canada.

In this case, the cockroach theory holds for Chinese money flows. If you see one cockroach, there are likely others. If the Globe and Mail found one Kenny Gu, then there are probably many others using similar financing channels.

Notwithstanding the fact that this scheme was skirting the rules against money laundering activity and violated Canadian tax laws, this all works as long as the property market is rising and liquidity is available to finance these loans. So what happens when the music stops?

In response to the popular outcry over housing affordability, the provincial government recently slapped on a 15% stamp duty on purchases of residential property by foreigners. The 15% tax has cooled the market and the buying stampede psychology has been stopped in its tracks. Now there are reports that the Great Ball of Money is rolling into Toronto and nearby Seattle.

From a global macro perspective, skyrocketing property prices in places like Vancouver, Toronto, Seattle, Sydney, and Melbourne can be attributed to excess liquidity sloshing around in China. Should China experience a banking crisis, the reverberations will be felt all over the world, not just through falling trade (see How bad could a China crisis get?), but financial linkages.

The music is still playing

For now, the music is still playing in China and any immediate risk of collapse is low. Bloomberg reports that Chinese authorities are ramping up loan growth again in a targeted lending program:

At least 2 trillion yuan (almost $300 billion) in new financing for lending has been amassed at the so-called policy banks, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The China Development Bank, the Export-Import Bank of China and the Agricultural Development Bank of China have raised a combined 3.4 trillion yuan ($509 billion) through bond sales and low-rate credit from the People’s Bank of China this year, the data show once funds to repay maturing debt is included. That’s almost eclipsed the record 2015 total.

In the process, the combined assets of the three policy banks has swollen to 21.3 trillion yuan — or bigger than the U.K.’s gross domestic product. By the end of 2016, policy bank assets will make up about 15 percent of the total banking sector, up from 8 percent three years ago, according Larry Hu, the head of China economics at Macquarie Securities Ltd. in Hong Kong.

And more is on the way: China will encourage policy banks to increase credit support to investment projects, according to a statement last week after a State Council meeting led by Premier Li Keqiang. That’ll give another dose of stimulus and grant President Xi yet more control over where the money should flow.

Indeed, Chinese money supply growth is rising dramatically again in a way that is reminiscent of another QE program (via Jeroen Blokland).

Risk levels are nevertheless rising. The Telegraph reported that BIS sounded the warning bells about China’s excessive debt ratios:

The Bank for International Settlements warned in its quarterly report that China’s “credit to GDP gap” has reached 30.1, the highest to date and in a different league altogether from any other major country tracked by the institution. It is also significantly higher than the scores in East Asia’s speculative boom on 1997 or in the US subprime bubble before the Lehman crisis.

Studies of earlier banking crises around the world over the last sixty years suggest that any score above ten requires careful monitoring. The credit to GDP gap measures deviations from normal patterns within any one country and therefore strips out cultural differences.

We’ve heard these kinds of warnings before from BIS. While the risks are clearly present, it is unclear when China might hit the proverbial debt wall. Michael Pettis studied the problem in June 2016 concluded that, even using optimistic assumptions, Beijing can keep the music going for another 2-3 years before it runs into a “disruptive adjustment”. If and when that happens, the financial linkages that I outlined in this post raise the vulnerability of the global financial system.

I meant to thank you for this post. My question, because I live here too, what happens when China hits that wall? Does money rush back into China or does even more flow out?

UBS recently indicated that Vancouver is the most overvalued city in the world: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-09-27/vancouver-london-top-list-of-cities-at-risk-of-housing-bubble

When China hits the wall the most likely outcome will see a severe correction in the Vancouver real estate market. I would not be surprised to see the magnitude to be comparable to the post-1982 Calgary bust. In addition, it has the potential to put considerable pressure on the Canadian banking system.