In the wake of the Brexit shock, Fed governor Jerome Powell was the first Fed speaker to give a speech, which gives some clue to the direction to Fed policy. While what the Fed does near-term is important to traders, the longer term thinking is important to investors as the definition of the Fed’s reaction function to events will affect the timing of rate hikes, the next recession and the next bear market.

Brexit risks

The Powell speech laid out two main concerns of the Federal Reserve. One was the global risks posed by Brexit:

These global risks have now shifted even further to the downside, with last week’s referendum on the United Kingdom’s status in the European Union. The Brexit vote has the potential to create new headwinds for economies around the world, including our own. The risks to the global outlook were somewhat elevated even prior to the referendum, and the vote has introduced new uncertainties. We have said that the Federal Reserve is carefully monitoring developments in global financial markets, in cooperation with other central banks. We are prepared to provide dollar liquidity through our existing swap lines with central banks, as necessary, to address pressures in global funding markets, which could have adverse implications for our economy. Although financial conditions have tightened since the vote, markets have been functioning in an orderly manner. And the U.S. financial sector is strong and resilient. As our recent stress tests show, our largest financial institutions continue to build their capital and strengthen their balance sheets.

It is far too early to judge the effects of the Brexit vote. As the global outlook evolves, it will be important to assess the implications for the U.S. economy, and for the stance of policy appropriate to foster continued progress toward our objectives of maximum employment and price stability.

Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan took a similar wait-and-see cautious tone in a Bloomberg interview last week:

Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas President Robert Kaplan said Britain’s vote to exit the European Union could slow growth and the most significant question raised by the decision lies in potential spillover effects as other countries ponder their own place in Europe.

“Is there contagion? What does Ireland do? What does Scotland do? What do other EU countries do?” Kaplan told Bloomberg in an interview Thursday in Washington. “In this case, political and economic are intersecting. And it will take a significant amount of time to see how all that unfolds.”

The Fed’s leading dove, Lael Brainard, had been hammering away on the theme of global linkages. Here is her speech from October, 2015:

Downgrades to foreign growth affect the U.S. outlook through several channels. First, weak growth abroad reduces demand for U.S. exports. Second, the expected divergence in U.S. growth increases demand for U.S. assets, putting upward pressure on the dollar, which, in turn, weighs on net exports. The estimated effect of dollar appreciation on net exports has been shown to be substantial and to persist for several years.6 Weak demand weighs on global commodity prices, which, together with the effects on the dollar, restrains U.S. inflation. Finally, the anticipation of weaker global growth can make market participants more attuned to downside risks, which can reduce prices for risky assets, both abroad and in the United States–as we saw in late August–with attendant effects on consumption and investment.

Brainard thinks that the global economy is fragile. Even though all may seem well in the United States, weak non-US growth will eventually pull down US growth:

Consider two possible scenarios. First, many observers have suggested that the economy will soon begin to strain available resources without some monetary tightening. Because monetary policy acts with a lag, in this scenario, high rates of resource utilization may lead to a large buildup of inflationary pressures, a rise in inflation expectations and persistent inflation in excess of our 2 percent target. However, we have well-tested tools to address such a situation and plenty of policy room in which to use them. Moreover, the persistently deflationary international environment, the gradual pace of increases in U.S. resource utilization, the estimated small effect of resource utilization on inflation, the likely low level of neutral interest rates, and the persistence of inflation below our 2 percent target suggests this risk remains modest. Financial markets appear to agree, as five-year inflation compensation is well below 2 percent.

Now, take the alternative risk: that the underlying momentum of the domestic economy is not strong enough to resist the deflationary pull of the international environment. A further step-down in global demand growth and a further strengthening in the dollar could increase the already sizable negative effect of the global environment on U.S. demand, pushing U.S. growth back to, or below, potential. Progress toward full employment and 2 percent inflation would stall or reverse. With limited ability to ease policy, it would be more difficult to move the economy back on track.

By contrast, vice-chair Stanley Fischer sounded a more hawkish tone in a CNBC interview:

“First of all, the U.S. economy since the very bad data we got in May on employment has done pretty well. Most of the incoming data looked good,” Fischer said. “Now, you can’t make a whole story out of a month and a half of data, but this is looking better than a tad before.”

He added, “Our primary obligation, it’s set out in the law, is to do what’s right for the American economy. Of course we take what happens abroad into account because it affects the American economy. … We’ll base what we do on what’s happening in the United States and what we think will happen.”

Based on the tone of the latest Fedspeak, it doesn’t sound like the Fed has fully bought into the Brainard “linkages” risk thesis just yet. For now, the world is still mesmerized by Brexit risk. If we use the Russia/LTCM crisis as a template, the Fed had been in a mild tightening cycle when the crisis hit. It responded with several rate cuts and began normalizing rates about nine months later. The chart below shows the Fed Funds target (in blue) along with the Russell 1000 (red) as an indication of the market response during that period.

The Russia/LTCM crisis is my base case scenario for the timing of the Fed’s rate normalization policy, though the rate cut part is in doubt as the markets appeared to have normalized very quickly. However, the wildcard is the question of how the Fed interprets the ongoing developments in the labor market.

Full employment?

The other focus of the Powell speech as employment and inflation. This is particularly relevant as we await the June Jobs Report on Friday morning to see if the weakness seen in May was an aberration.

After several years of improving labor market conditions, recent data have been sending mixed signals on the level of momentum in the economy. Business investment has weakened, even outside the energy sector. Growth in gross domestic product (GDP) is estimated to have slowed to a rate of only 1-1/4 percent on an annualized basis over the fourth quarter of last year and the first quarter of this year. Incoming data do point to a rebound. For example, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model, which bases its projection on a range of incoming monthly data, estimates growth of 2.6 percent in the second quarter. In contrast, the labor market data, especially the monthly increase in payroll jobs, after displaying considerable strength for several years right through the first quarter of 2016, weakened significantly in April and May. While I would not want to make too much of two monthly observations, the strength of the labor market has been a key feature of the recovery, allowing us to look through quarterly fluctuations in GDP growth. So the possible loss of momentum in job growth is worrisome.

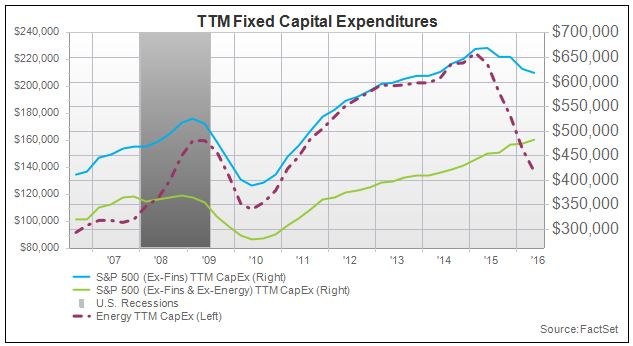

Wait! Did he say “weak business investment”? I pointed out on the weekend that analysis from Factset shows that capex was still growing at a healthy rate on an ex-energy and finance basis (green line):

The difference between the Powell comment about “weak business investment” and above chart illustrates the main policy risk as we await the June Jobs Report. The Fed may be mis-interpreting incoming data as weakness, when the economy is actually strengthening. In that case, we may see lower for longer in the short run, only to be followed by a realization that Fed policy is behind the curve and the response of a series of rapid rate hikes that pulls the US and global economy into recession.

As an example, one of the concerns raised by the weak May Jobs Report was that the unemployment rate had dropped, but for the bad reason that the participation rate had fallen. Here is what Janet Yellen said in her Congressional testimony about the participation rate (see WSJ video).

- The Labor Participation Rate (LPR) has been falling for some time because of demographics

- Weak labor markets has also pushed up LPR because discouraged workers leave the work force

- LPR has been flat recently, which Yellen interpreted positively as signs of cyclical gains

The end game

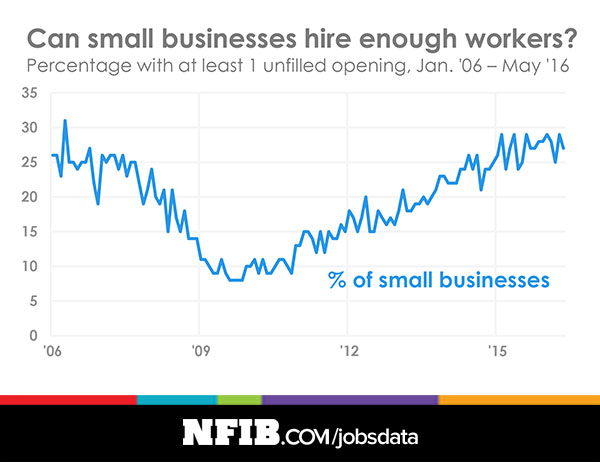

I have laid out the case that there is little slack in the labor market. Should we see weaker than expected employment growth, it’s a sign of a full employment economy, not economic weakness. Under those circumstances, I expect that the debate will rage within the Fed over differing interpretations over the coming months as rates stay on hold while the Brexit risk premium fades.

Despite her dovish reputation, Yellen has rejected Evans Rule 2.0 (don’t hike until you see inflation at 2%) and stated that she doesn’t want to approach the Fed’s 2% inflation target from above:

I continue to believe that it will be appropriate to gradually reduce the degree of monetary policy accommodation, provided that labor market conditions strengthen further and inflation continues to make progress toward our 2 percent objective. Because monetary policy affects the economy with a lag, steps to withdraw this monetary accommodation ought to be initiated before the FOMC’s goals are fully reached.

Assuming that the Brexit crisis blows over, one of the greatest market risks as we approach the spring and summer of 2017 is the Fed stays on hold too long and then recognizes belatedly that it is behind the inflation fighting curve. It will then have to respond with a series of staccato rate hikes that plunge the global economy into recession.

I have come to believe that James Bullard’s St. Louis Fed is the key to watching for rate adjustments. His is the strange dot on the Dot Plot that showed one more rate increase and then done for the next two years and no long term projection beyond that. The other governors projected multiple hikes for the next few years and a high future average.

His economic group have stopped thinking about long term ‘norms’ and things mean reverting back to those old norms. That is the old thinking pattern of the other Fed governors when their rate projections ramp up to 3-4% over the next few years and they project a long term average in the 3.75% area.

Bullard’s new approach is looking just 2.5 years ahead which he names a ‘regime’. The current ‘regime’ has employment about as low as it can go, GDP growing at 2% and inflation close to 2% target. That regime calls for one more hike any time over the next few meetings and then done.

This new work gives us an inside look at what a building full of smart Fed economists with the best information are thinking. I believe this is a VERY BIG DEAL.

I am going to use their future ‘regime’ announcements a great guide to where Fed policy should be going. Let’s say inflation starts ramping up and they change ‘regimes’ in response. I will heed the call and change my investment approach. Same if they see a recession regime. I will listen. If like now, they see stability, I will expect investors to be surprised rates are not going up and I will expect investors to accepting ‘lower for longer’. This means I will focus on dividend yield driving stocks higher.

If Fed policy differs from their ‘regime’ outlook, then I would be wary of problems developing. For example, if Bullard says one rate hike and no more but the committee hikes more often, I would worry that negative economic outcomes would ensue.

I have signed up to get James Bullard’s speeches and media appearances emailed to me whenever he is in the media. It’s easy to get signed up. Go to the St. Louis Fed website. If you can’t find the spot to sign up (I couldn’t) just find a phone number there and they will sign you up over the phone.

Here are two links they sent me. One is him on Bloomberg TV outlining the new research. The other is his very recent speech.

Bullard on Bloomberg TV explaining things.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/videos/2016-07-01/bullard-u-s-unemployment-about-as-low-as-it-can-go

Bullard’s speech explaining the new policy

https://www.stlouisfed.org/from-the-president/speeches-and-presentations/2016/a-new-characterization?utm_source=FPUpdate&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=FPContentUpdate#text

Cam,

Awesome job in providing an update on the 30,000 feet view of your larger view of the economy/bull market cycles. I guess we are/or shortly will be, entering the 4th stage of the expansion/contraction cycle

Thanks for your awesome analysis, as always.

Cam- One query, one quibble and one oservation.

1) Do you see any significance to the fact that Powell refers to ‘continued progress toward our objectives of maximum employment and price stability’ rather than the usual Yellen mantra of ‘inflation continues to make progress toward our 2 percent objective’?

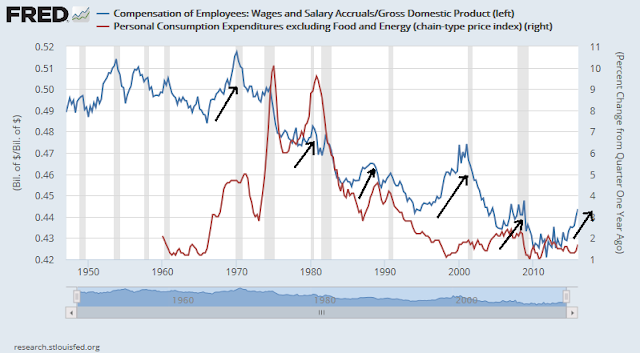

2) I do not perceive any consistent relationship between employee compensation (COMP) and personal consumption expenditure (PCE) in the chart you present. COMP increased from 1993-2000 while PCE declined. COMP increased from 2005-2009 while PCE remained flat. PCE increased sharply around 1972 and again from 1975-1980 despite DECREASES in COMP at those times. Of course one can make arm-waving arguments for each and every case (easy credit/tight credit, etc.) but that is simply admitting that the relationship, if any, doesn’t work ergo there is no support to using these data to deduce that current wage increases should lead to increased personal expenditures and then inflation.

3) I winter in Florida and I observe billboards and posters exhorting people to engage particular legal firms to initiate permanent disability claims on their behalf and extolling their high rates of success. These pitches have partly supplanted the ‘No money, no income no problem! We can put you into the car, house, etc. of your dreams with no credit check’ pitches that led to the subprime crisis (and which seems to be in the process of being repeated in car loans). I have seen reports claiming exceptionally high disability rates in several states (I believe the Appalachian states were high on the list) and suggesting this is part of the reason for the declining workforce participation rate.

Any thoughts?

Roy

1) As per the FOMC minutes, I imagine that they are less concerned about inflation right now, but that can change depending on how the market reacts to Brexit, Italian banks and the Friday NFP release

2) The Fed has used a Phillips Curve framework that trades off inflation against unemployment. Regardless of how you or I perceive the weakness of that relationship you have to respect how they analyze things in terms what Fed policy is likely to be

3) No idea on the disability issue. I haven’t studied it.

Cam,

Do you have any thoughts on gold? According to UBS, real US interest rates is the key determinant of gold price. Seeing as there might be increasing inflationary pressures that decrease real interest rate do you think gold have more room to climb? Thanks.

One would imagine that this would be a favorable environment for gold, but be aware that the Commitment of Traders reports show that speculators are in a crowded long position in gold so be prepared for nasty setbacks

1. The US Fed and economist community at large has been pondering over the question of when to raise interest rates from circa 2007. I see these headlines every so often with lots of analysis, graphs, tables etc. Since 2007, rates have been on a downward trajectory is the evidence at hand. One can dream of raising rates, but exactly the opposite is happening.

2. Yes, wage inflation in the US may be in the pipeline, but headline CPI in the US remains below 2%. The US fed would love to have CPI over 2%. Raising rates would push the CPI down further. Why would the US fed want to do so?

3. We are now seeing outright currency wars, but no one is taking about it in the lay press, or at least not yet. Negative interest rates in Europe are a way to push down the value of the Euro (against US$). Yes, such an experiment failed in Japan, granted. Relative to the value of the Euro, the $ may be priced “as though” fed funds are trading at say 1-1.25%. I do not have a fair mechanism to come to an accurate estimate of 1-1.25%; it is a number out of a hat. I am sure, an economist at an elite university has a way to come to an exact value of fed funds rate, based on how negative the interest rates are at a point in time. My conclusion is that the US fed’s task of raising interest rates has already been done by negative interest rates overseas (tail is starting to wag the dog).

4. Let us each ask the question, “is it futile to ask when the fed will raise interest rates”? Possibly, since it is only seven years give or take that we have been pondering over this question. Were we to ask the same question to the US fed, their answer would be “we are data dependent”!! Ben Bernanke said that he never thought back in 2007-08 that we would be in 2016, and still talking about low rates.

5. Let us examine the question of fed funds rates further, from a political angle. Presuming liberals in Europe, Canada, and US and other parts the world were to have their way, the world would see even higher taxes, to help the poor through free college tuition, subsidized housing and healthcare etc. Let us not kid ourselves, that such liberal policies amount to a tax on businesses. One can argue whether such liberal policies amount to increased economic activity or depressed economic activity, but liberal Europe tells us that such policies are generally a negative for economic activity. Not trying to politicize this debate, but simple answer/conclusion here is that the US fed has its hands tied when it comes to raising rates, as the government itself is doing the job!

6. Let us also ask the question what happens to global inflation if Saudi Arabia cuts petroleum production by 10%. Yes, inflation will crack higher and the US fed will be forced to raise rates.

7. What happens if Scottish referendum to separate from UK comes to pass or say Italy or France were to exit the EU? The US treasuries would rally with yield in the 0.25% range on the ten year, give or take. The yield curve will flatten, and the US Fed will find it even harder to raise fed fund rates.

My conclusions: E Pluribus unum (one amongst many). The US fed is one factor amongst many that decide the rate debate in a globalized economy. Yes, in the past five decades, things were different. US inflation is also just one factor amongst many that govern the actions of the US fed. We are in a world of deflation, and it is difficult to predict or plan rate rises. Durable solution IMHO would be to tweak fiscal policies (cut taxes, cut welfare benefits, promote free markets). These require political action which is not coming. Mohammed El Erian is right, Monetary policies can do only so much, and we are at the end of the road.

How does one invest in such an environment? Stay diversified in high quality stocks, bonds, real estate, precious metals/hard assets, and cash (say 20% each, give or take, for long term portfolio). Pay attention to technicals and asset prices relative to bond yields (yes, if the US fed decides to enact a QE or push yields to negative territory, stocks would go higher). If the US fed raises rates, it would reduce GDP and would be negative for earnings).

Cam, I appreciate your insightful technical analysis. Thanks.

D.V. – Just for information, e pluribus unum means ‘out of many, one’ in reference to the United States of America where many states came together to form a single nation. The European Union is an attempt to partially achieve the same thing. The fact that it is partial is what seems to cause problems. Major differences among groups of American states led to the U.S. Civil War when the Federal Government refused to let them secede. Major differences among E.U. members is leading towards secession but can be effected without war which, after all, is simply politics by another means.

Roy, I am aware of the Latin phrase e pluribus unum as the motto of the US, but I am using it in a different context. There is whole lot else going on in the financial markets. IMHO, EU is a flawed union (see my other posts on this forum), a gift that started with Grexit, that is going to keep giving. My point is that in a globalized world, the US fed remains but one factor amongst a plethora of factors, hence e pluribus unum. Yes, the fed is one out of many (factors).

On a side note, here is a quote from Wikipedia “The traditionally understood meaning of the phrase was that out of many states (or colonies) emerges a single nation. However, in recent years its meaning has come to suggest that out of many peoples, races, religions, languages, and ancestries has emerged a single people and nation—illustrating the concept of the melting pot”.

Let me go a little further and state that I remain agnostic to the use of the phrase by the US. It may have been relevant back in 1776, but the world has changed, and so has the US, making the phrase only of historical significance, if that.