Rather than indulge in instant analysis, I wanted to give myself a few days to reflect on Janet Yellen’s speech on Monday (see full transcript). In doing so, I learned a number of things about Fed policy that I didn’t know before:

- How much does the Fed want to raise before it considers rates to be “normalized”

- What it means to allow the economy to run a little “hot” because of slack in the labor markets

- What the hurdles are to next raise rates

- From Ben Bernanke: The debate over how to implement the Phillips Curve in monetary policy

Normalization = 1% rate hike

One of my big surprises was what Yellen considered to be the “neutral” Fed Funds rate. My estimate of the Taylor Rule target based on various inputs had put the “neutral” rate north of 3%, but Yellen thinks that rates only have to rise by about 1% to get to neutral:

One useful measure of the stance of policy is the deviation of the federal funds rate from a “neutral” value, defined as the level of the federal funds rate that would be neither expansionary nor contractionary if the economy was operating near potential. This neutral rate changes over time, and, at any given date, it depends on a constellation of underlying forces affecting the economy. At present, many estimates show the neutral rate to be quite low by historical standards–indeed, close to zero when measured in real, or inflation-adjusted, terms. The current actual value of the federal funds rate, also measured in real terms, is even lower, somewhere around minus 1 percent. With the actual real federal funds rate modestly below the relatively low neutral real rate, the stance of monetary policy at present should be viewed as modestly accommodative.

This statement is an indication of the dovishness of the Yellen Fed.

No inflation “overshoot”

On the other hand, investors shouldn’t take the Fed’s dovishness for granted. Despite all of the Fedspeak about how they are willing to let the economy run a little “hot” (read: tolerate higher inflation) because of slack in the labor market, the Fed is not willing to overshoot its inflation target and approach its 2% target from above. Yellen stated that monetary policy operates with a lag and therefore she is unwilling to risk an inflationary overshoot:

I continue to believe that it will be appropriate to gradually reduce the degree of monetary policy accommodation, provided that labor market conditions strengthen further and inflation continues to make progress toward our 2 percent objective. Because monetary policy affects the economy with a lag, steps to withdraw this monetary accommodation ought to be initiated before the FOMC’s goals are fully reached.

Hurdles for the next rate hike

In her speech, Yellen sounded optimistic about the trajectory of economic growth, but she went on to set up some tests in light of the softness evidence in the last Employment Report:

Over the past few months, financial conditions have recovered significantly and many of the risks from abroad have diminished, although some risks remain. In addition, consumer spending appears to have rebounded, providing some reassurance that overall growth has indeed picked up as expected. Unfortunately, as I noted earlier, new questions about the economic outlook have been raised by the recent labor market data. Is the markedly reduced pace of hiring in April and May a harbinger of a persistent slowdown in the broader economy? Or will monthly payroll gains move up toward the solid pace they maintained earlier this year and in 2015? Does the latest reading on the unemployment rate indicate that we are essentially back to full employment, or does relatively subdued wage growth signal that more slack remains? My colleagues and I will be wrestling with these and other related questions going forward.

Tim Duy thinks that the Fed will need a couple months of solid data before committing to a rate hike, which suggests that July is off the table:

The May employment report killed the chances of a rate hike in June. And it was weak enough that July no longer looks likely as well. I had thought that, assuming a solid May number they would set the stage for a July hike. That seems unlikely now; they will probably need two months of good numbers to overcome the May hit. The data might bounce in the direction of July, to be sure. Hence Fed officials won’t want to take July off the table just yet, so expect, in particular, the more hawkish elements of the FOMC to keep up the tough talk.

The Phillips Curve debate

Finally, an insight came from an unusual source, Ben Bernanke, about how the Fed is wrestling with the Phillips Curve. In a Brookings Institute round table, Bernanke was asked the question, “Is the Phillips Curve dead?” (click this link for the short video).

For newbies, the Phillips Curve describes an inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment. In the short run, policy makers can trade off between two evils, inflation and unemployment.

Bernanke said that, despite all of its flaws, the Phillips Curve is still a good guide for monetary policy. However, there is some debate over what to put in the “inflation” axis for the Phillips Curve, actual inflation, or inflationary expectations? If they were to use inflationary expectations, the question becomes where expectations are anchored.

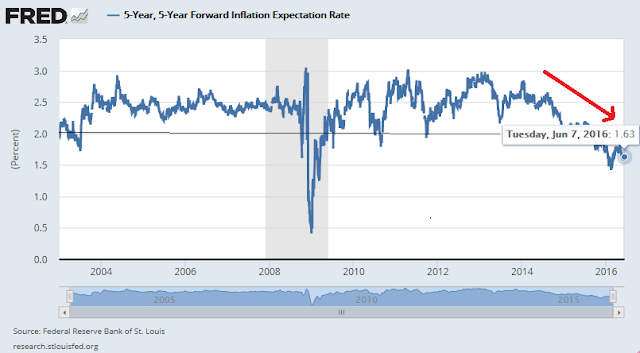

Here is a chart of forward inflationary expectations, which has been falling. If inflationary expectations are anchored at the widely telegraphed Fed target of 2%, then the current trajectory of monetary policy makes sense. If, as the likes of Lael Brainard have argued in the past, the risk that inflationary expectations are becoming unanchored to the downside, then Fed policy needs to be easier.

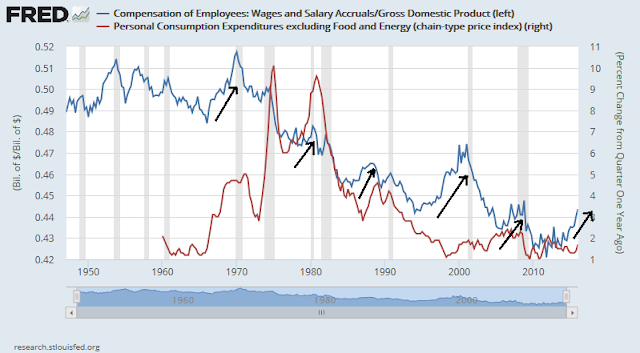

Here is a chart of employee compensation as a % of GDP (blue line) and core PCE (red line). Notwithstanding the downward drift in employee compensation over the past few decades, past upticks in employee compensation have coincided with upward pressure in core PCE. These episodes have tended to occur in the late stages of economic expansions, which were arrested by monetary policy tightening which usually resulted in recessions.

So is the latest rise in employee compensation a typical cyclical effect which should be met with a response by tighter monetary policy? Should the softness in the May Employment Report persist, I would expect that debate between the hawks and the doves in the Fed to heat up.

I plan to have more thoughts on how to read the huge miss in the May Employment Report in my next post.