As the oil price touched $50, there has been a growing paradigm shift, a sort of “this time is different”, consensus forming about the long-term outlook for oil prices. Amy Myers Jaffe of UC Davis recently addressed the 69th CFA Institute Conference and made the following bearish points about the long run trajectory of oil prices:

- Demand: Global demand growth is set to slow, flatten and perhaps fall as countries start to adopt alternative energy sources. Indeed, Bloomberg recently reported that there are more people employed in renewable energy in China than oil and gas. Similarly, solar power related employment has surpassed employment related to coal and oil and gas combined in the United States.\

- Supply: The fracking revolution is a revolution. For the first time in history, advances in engineering has allowed us to extract oil and gas from oil bearing rock, which means that any geology that formerly produced oil, such as Pennsylvania, is has the potential to produce oil again. Jaffe did not, however, address the cost question and said in so many words that these are engineering problems, which can be solved over time.

Like OPEC, they [Big Oil] assumed the value of their reserves of this finite, critical commodity would, more or less, keep rising over time. So a barrel not produced today, even if it cost a lot to find or acquire, is effectively money in the bank. This is why the majors obsess over their reserves replacement ratio, measuring how many new barrels come in to replace the ones they pump out.

Now, the upcoming Saudi Aramco IPO raises one troubling possibility: That the assumption of endlessly rising reserve value may no longer hold true.

A flurry of paradigm-shifting announcements out of Saudi Arabia came soon after a speech in October by BP’s chief economist. He posited that the shale boom undercut the notion of peak oil supply, while efforts to curb carbon emissions raised the possibility of peak demand.

Denning went on to suggest that the upcoming partial privatization of up to 5% of Saudi Aramco representing a Saudi strategic shift to produce at any price, rather than to bank the oil in the ground because it is becoming a commodity with diminishing value.

Saudi Arabia’s sudden desire to sell shares in its national champion and generally shift the entire economy away from its oil addiction suggests it at least entertains those possibilities. It also provides a rationale to maximize production at any price, rather than risk barrels being left worthless in the ground.

Shale boom + carbon emissions curb = Peak Oil demand. It’s time to change the thinking on the management of this resource and sell it as fast as possible because some of those assets will become stranded in the future. Call it the Hot Potato Theory of oil.

Hot Potato Theory = This time is different

How plausible is the Hot Potato Theory? Notwithstanding the current market conditions, take a look at this multi-decade chart of oil supply and demand from Yardeni Research. Past history shows that demand has kept on growing.

Going back to 1987, oil demand has risen more or less steadily with minor interruptions from recessions. One of the underlying assumptions of the Hot Potato Theory calls for demand to start rolling over.

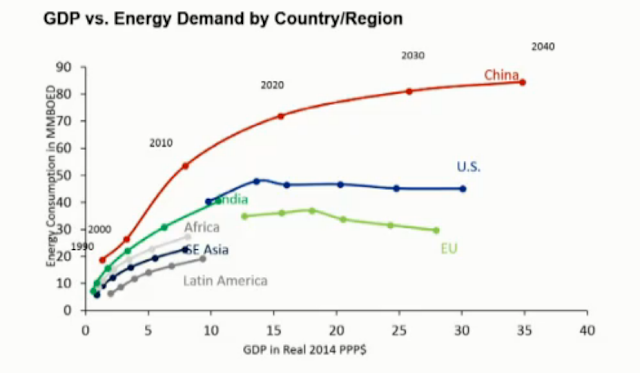

A bet against rising oil demand is a bet against emerging market economic growth. In the short term (1-3 years), it would mean halting EM growth in its tracks.

If we were to make the assumption that energy demand in the EM countries is going to start flattening out, much as they have in the developed countries, more development translate to greater industrialization and higher energy usage intensity. While China is an outlier in its inefficient use and its energy intensity will likely start to flatten out and eventually fall, we also have to consider the developmental cycle in other EM economies. A bet on near-term falling or flattening demand is still a bet that EM growth slows dramatically. Such a scenario implies tanking EM growth and, in all likelihood, a prolonged global recession.

As oil prices have fallen, Barron`s reported that Boeing has warned that airlines are becoming less concerned over fuel economy. So expect a very bump ride if you expect a demand dropoff in the near future.

To summarize, a bet on flattening or falling oil demand is a “this time is different” bet, at least in the 1-3 year time frame. While history has seen earth shattering transformations in technology and behavior, a “this time is different” is one of the most dangerous bets that an investor can make.

To be sure, there is far more supply on the market. The chart below depicts the rise of oil production from US tight oil and, to a lessor extent, Russia in the last few years. The appearance of this new supply has upset the old order. Moreover, the Saudi desire to pump at all costs and maintain market share is probably linked to its rivalry with Iran, rather than any calculated attempt at economic maximization.

The political risk of restructuring

Saudi Arabia`s deputy crown prince Mohammed bin Salman recently unveiled its Vision 2030 restructuring plan to great fanfare. The plan is full of McKinsey slogans, but short on details and it received with great skepticism (see an example here from FT Alphaville). Moreover, Vision 2030 contained many ambitious objectives like this one that contained prescriptions on how to diversify the economy, where evidently neither the Saudis nor their McKinsey consultants were aware of Michael Porter’s work on industry clusters in The Competitive Advantage of Nations:

Our aim is to localize over 50 percent of military equipment spending by 2030. We have already begun developing less complex industries such as those providing spare parts, armored vehicles and basic ammunition. We will expand this initiative to higher value and more complex equipment such as military aircraft. We will build an integrated national network of services and supporting industries that will improve our self-sufficiency and strengthen our defense exports, both regionally and internationally.

In fact, the Saudi reliance on McKinsey is reminiscent of Miachiavelli`s warning about mercenaries. Simply put, mercenaries just want your money, but you can’t count on their loyalty when the going gets tough:

Mercenaries and auxiliaries are useless and dangerous; and if one [a prince] holds his state based on these arms, he will stand neither firm nor safe; for they are disunited, ambitious and without discipline, unfaithful, valiant before friends, cowardly before enemies; they have neither the fear of God nor fidelity to men, and destruction is deferred only so long as the attack is; for in peace one is robbed by them, and in war by the enemy. The fact is, they have no other attraction or reason for keeping the field than a trifle of stipend, which is not sufficient to make them willing to die for you. They are ready enough to be your soldiers whilst you do not make war, but if war comes they take themselves off or run from the foe; which I should have little trouble to prove, for the ruin of Italy has been caused by nothing else than by resting all her hopes for many years on mercenaries, and although they formerly made some display and appeared valiant amongst themselves, yet when the foreigners came they showed what they were.

We have seen instances in the past where countries and local authorities have tried various schemes to pivot and get lessen their economy’s reliance on natural resources as a source of growth. Most have failed. The greatest success was been the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund, which took oil revenues and invested the proceeds outside Norway as a way of avoiding local boondoggles – which is not a feature of the Saudi plan.

The new fracking technology will likely put a ceiling on the price of oil for some time, while oil prices may not be sustainable at $30-50, higher prices will be met by marginal production, which can be started by the shut-in US tight oil in relatively short order. These price ceiling constraints implies that the Saudi budget will be under considerable pressure for some time.

Such an environment creates serious tail-risk over the next 5-10 years as political discontent is likely to rise, not just in Saudi Arabia, but in many oil producing countries. As an example, Nigeria is already experiencing supply problems due to a local insurgency (via Bloomberg):

It’s hard to see any long-term let-up given Nigeria’s record on fixing this problem. The previous wave of discontent, which hit a peak in 2009, only came to an end when President Yar’Adua offered amnesty, training programs and monthly cash payments to nearly 30,000 militants, at a yearly cost of about $500 million. Some leaders of the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND), the militant group, got lucrative security contracts.

But the failure to properly address local grievances means it was only a matter of time before another wave of angry young men took up the fight for a better deal for southern Nigeria. The crisis has been hastened by new president Muhammadu Buhari’s termination of the ex-militants’ security contracts and his seeking the arrest of former MEND leaders.

The Avengers now say they want independence for the Niger River delta.

And it’s not as if Nigeria’s oil woes are limited to the militants. Exxon had to declare force majeure on Qua Iboe exports after a drilling platform ran aground and ruptured a pipeline, while Shell did similar with Bonny Light exports after a leak from a pipeline feeding the terminal.

Stratfor recently featured a report on the jihadist threat in Saudi Arabia, which comes from the dual threat of IS and Al Qaeda. In effect, Saudi Arabia faces the tail-risk of becoming a failed state should the Kingdom fail to properly manage the intersection of falling oil revenues and the expectations of its citizens. A report by Global Risk Insights added more color with an even more pessimistic view:

With the strain on its finances from the oil price trough and its military campaigns abroad, Saudi Arabia is in a weakened condition. The basis of its internal control is its enormous capacity to pay for popular support through the maintenance of a generous welfare state.

The likelihood of increasing economic hardship (25% of the population now lives in poverty, with youth unemployment at 30%) and Shia retribution for ISIS-orchestrated attacks, together with continued cooperation with Iran and the US in the fight against ISIS and the House of Saud’s failure to protect Sunnis in Yemen and Syria, means that the ability of a challenger, such as ISIS, to make a successful bid to displace the leadership role of the House of Saud is high.

Recent reports of discontent and instability within House of Saud itself further enhance the opportunity for a challenger to succeed.

The House of Saud is facing its most trying challenge since its conflict with the Ottomans 200 years ago, and the implications are enormous.

The country will likely go through a bloody transition with conflict amongst Salafi factions, between Salafis and other Sunni groups, and between these groups and Shias. Conflict will continue until one of those groups emerges victorious or, more likely, the country is divided between them.

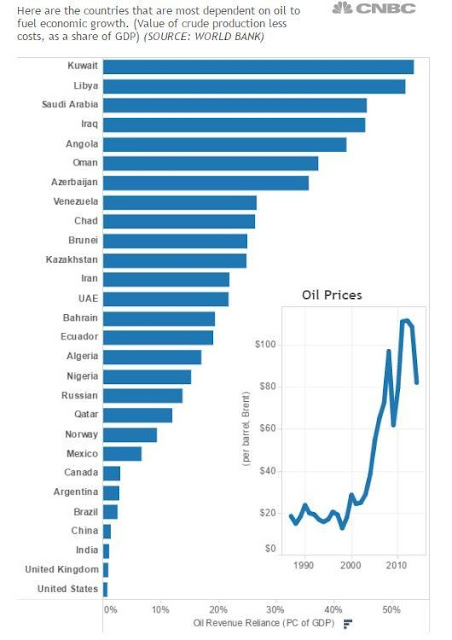

The problem isn`t just limited to Saudi Arabia. This chart shows oil exports as a percentage of GDP (via WEF). The list is headed by Kuwait, followed by Libya. Saudi Arabia is third on the list.

This chart shows the reliance on fuel as a percentage of merchandise exports, which includes commodities such as natural gas and coal. Saudi Arabia is 11th on the list.

A recent Bloomberg story detailed the struggles of Alaska governor Bill Walker of managing the State`s collapsing oil revenues against the expectations of its residents used to receiving dividend checks. Many countries at the top of the above list don’t have the same kind of governance structures present in modern western democracies. If Alaska is having trouble managing its budget and expectations, then what’s the political tail-risk in these other countries?

The near-term path for oil prices

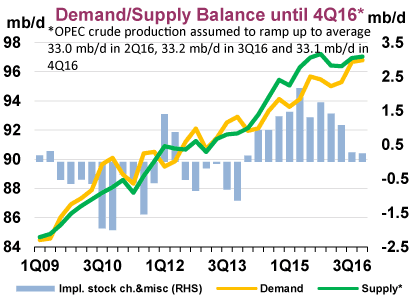

The IEA projections show that oil supply and demand is likely to come into better balance late this year, which should help prices rise.

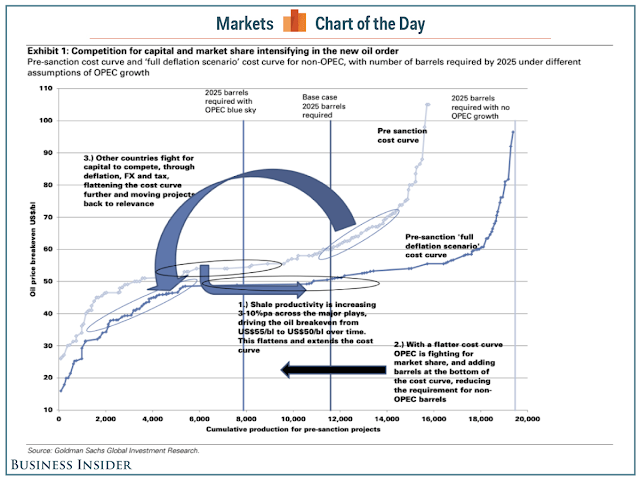

A recent Goldman Sachs research report (via Business Insider) postulates a much flatter cost curve for oil production because of ever improving tight oil technology, whose production can be shut-in and restarted quickly, and the desire of OPEC countries to maintain market share.

If we are to accept the Goldman thesis about an equilibrium price at or about current levels because of a new and flatter cost curve, these prices are below the minimum budget breakeven for many oil producing countries and the risk of sudden price spikes from geopolitical disruption rises. At a minimum, it would suggest an unstable equilibrium, with prices in the $40-60 range punctuated by spikes from more frequent supply disruptions.

So much for the Hot Potato Theory for the next few years. Tactically, however, the intersection of $50 oil and the recent WSJ article “The New Oil Traders: Moms and Millennials“, which detailed the story of apparently inexperienced day and swing traders gravitating toward leveraged crude oil ETFs suggests that the latest strength in crude prices may be overdone. A more prudent course of action for investors would hold a core position, buy the dips and lighten up on rallies.

Disclosure: Long SU

Very interesting report. Thanks.

I watch spot oil commodity versus the 5 year forward. The spread has narrowed to $5 from $20 when oil was at its low in February. When the spread narrowed that much since the peak price in 2014, energy stocks topped and fell. It shows short term extreme optimism.

To enlarge on Ken’s point, the contango (spread between futures and spot) has narrowed considerably. When the contango was high, it was profitable to buy physical oil, store it and sell it for forward delivery to lock in an instant profit. That trade, which accounted for a lot of inventory that was sloshing around, is pretty much all gone.

Really good article. Not many in or out of the oil industry understand this topic as well as you do.

Thank you. That’s quite a compliment coming from a former XOM man like you.