The closely watched April PCE moderated as expected. Headline PCE came in 0.3%, in line with expectations, while core PCE was 0.2% (blue bars), which was softer than expectations. Supercore PCE, or services ex-energy and housing, also decelerated (red bars). This latest print represents useful progress, but won’t significantly move the needle on Fed policy.

The worrisome development is the global trend of transitory disinflation. The Citi Inflation Surprise Index, which measures whether incoming inflation data is beating or missing expectations, is bottoming in most countries and rising again. If this continues, any expectations of ongoing rate cuts are likely to be pulled back.

Now that 2024 is nearly half over, it’s time to peer into 2025 to see the upside and downside factors that are expected to affect inflation and the Fed’s interest rate trajectory. The three main factors to consider are changes in immigration policy and how they affect employment; the evolution in productivity; and the possible political effects of the election on inflation.

Immigration and labour supply

Immigration has become an increasingly touchy subject in the 2024 election. What’s surprising is the degree of agreement about not only restricting illegal immigration, but also the willingness to shrink the pool of unauthorized workers.

The Fed has weighed in on this touchy topic. When asked about the labour market, Fed Chair Jerome Powell said during the December post-FOMC press conference that, “The labor force participation rate has moved up since last year, particularly for individuals aged 25 to 54 years, and immigration has returned to pre-pandemic levels. Nominal wage growth appears to be easing, and job vacancies have declined.”

In particular, the prime age (25–54) labour force participation rate (red line, right scale) has recovered quicker post-pandemic than the overall participation rate (blue line, left scale). Powell hinted that immigration may serve some role in supplying more workers and curbing wage growth. “Does labor force participation have much more to run? It might. Immigration could help, but it may be that, at some point—at some point, you will run out of supply-side help, and then it gets down to demand, and it gets harder.”

So what happens if there is a border bill that either restricts unauthorized immigration or implements a mass deportation of illegal workers? I looked at the data to test the hypothesis that unauthorized immigration is expanding the labour supply more than normal.

Unauthorized workers mostly toil in low-skilled and low-wage jobs. From a policy standpoint, few are worried about the Canadian who sneaks across the U.S.-Canada border to work at a six-figure job as a project manager at GE. The Atlanta Feds’ Wage Growth Tracker shows that workers with high school education (green line) has usually lagged overall wage growth (blue line), but the rate of wage increase has exceeded the median in the post-pandemic era. If there is an excess supply of unauthorized workers during that period, they should be depressing wage growth, which is not evident in the data.

Here’s another way of analyzing wage growth in greater detail. The accompanying chart shows the average hourly earnings of production and non-supervisory workers (black line), of retail trade workers (red line) and of leisure and hospitality workers (blue line), all normalized to 100 in January 2019, which is about a year before the onset of the pandemic.

While low-wage workers are concentrated in retail and leisure and hospitality, retail employment tends to require a higher skill level and have a language requirement for client-facing positions compared to leisure and hospitality workers. As the chart shows, average hourly earnings for retail workers have lagged the overall average in the post-pandemic era, while leisure and hospitality average hourly earnings have been stronger. As unauthorized workers tend to cluster more among leisure and hospitality, excess supply in this group should show up as depressed wages not higher ones.

Now imagine that in the 2025 post-election world the White House and Congress come to an agreement on an immigration bill. Regardless of whether the bill just restricts the supply of illegal immigrants or takes active steps to deport them, it will worsen labour supply at the low-wage end of the market, tighten the jobs market and create upward pressures on inflation.

The market is currently discounting one rate cut in 2024, which is expected to occur at the September FOMC meeting. All else being equal, any immigration bill to restrict labour supply in an already tight jobs market may resolve itself in no rate cuts and possibly rate hikes in 2025.

The productivity wildcard

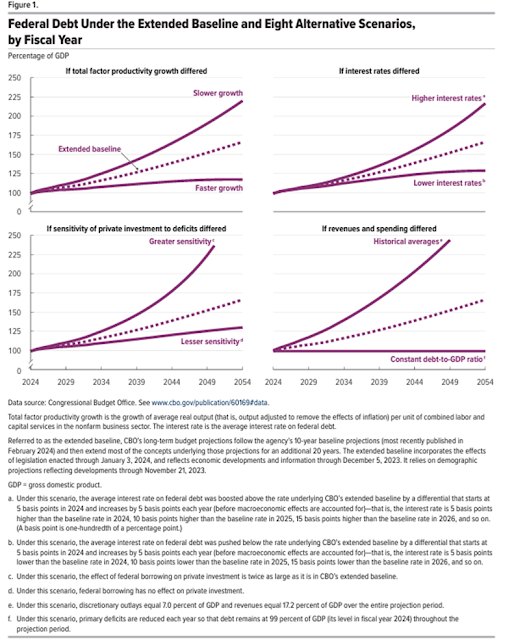

Productivity is the cure for inflation. Better productivity is an offset to higher growth and wages. Analysis from the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (top left chart) dramatically shows how productivity matters and how it affects not only inflation, but also the degree of fiscal room the government will have in the future.

The question of how productivity evolves has been a puzzle for Fed policy makers as productivity gains have been noisy. Powell discussed this policy dilemma at the May post-FOMC press conference: “We saw a year of very high productivity growth in 2023, and we saw a year of, I think, negative productivity growth in 2022. So I think it’s hard to draw from the data.”

As the accompanying chart shows, changes in productivity (blue line) are very noisy. It’s not unusual to see a leap in productivity when the economy revives from a recession. Economic output rebounds, but the number of workers is still low, which shows up as higher output per worker, or a productivity improvement. Productivity fell and went negative after the initial leap in the post-pandemic era, and it has risen again. What’s different this time is the prime age participation rate is also rising, indicating that productivity gains are not the result of fewer workers, which is a constructive development.

There are several schools of thought on productivity. The conventional view is that changes in productivity are noisy and Fed policy makers can’t reliably depend on productivity gains to moderate inflationary pressures.

A more constructive view is that the adoption of AI will drive powerful productivity gains in the coming years. There are numerous anecdotes of productivity gains through AI. One example can be found in this paper from the world of investing that found “machine learning models not only generate significantly more accurate and informative out-of-sample forecasts than the state-of-the-art models in the literature but also perform better compared to analysts’ consensus forecasts”.

On the other hand, the excitement over AI and large language models sounds remarkably like the hype over self-driving cars about 10 years ago. AI can get you 90–95% of the way, but the last 5% or 10% represents a last-mile problem that’s very difficult to solve. The St. Louis Fed published a paper that projected the pace of AI adoption to be similar to that of PC adoption, which is a cycle with an elongated pace of productivity gains.A more nuanced view is that PPP and inflation-adjusted productivity have been gaining steadily on a global basis, aside from Japan and Italy. The only difference is the strength of the USD.

Election effects

While it’s always difficult to predict electoral outcomes and it could be argued that polls aren’t very meaningful until the campaign begins in earnest in September, current market expectations of aggregated betting odds has Trump leading Biden despite his felony convictions last week.

With that in mind, Bloomberg reported that Deutsche Bank economists project that Trump’s proposed tariffs are expected to raise headline PCE by 1.2% and core PCE by 1.4%. This will force the Fed’s hand to pivot to raising rates.

In addition, investors will have to be prepared for the second-order effects of trade policy and Fed policy. If Trump, who is a self-professed “debt and low interest rate” guy, tries to politicize or change either the Fed Chair or the make-up of the Fed Board of Governors in order to force lower rates, expect USD weakness, accelerating inflation and possibly stagflationary growth.

In conclusion, I peered into 2025 to see how U.S. inflation may evolve with specific focus on changes in immigration policy and how they affect employment, the evolution in productivity and the possible political effects of the election on inflation. Upward pressures on inflation will come from changes in immigration policy and a Trump win. Productivity gains are uncertain and AI-driven gains are likely to take a long time to be realized.

Such an environment is typical of a mid- or late-cycle expansion. It is bond price unfriendly, and neutral or positive for stock prices, depending how the nominal growth outlook evolves.

Cam:

How can low interest rate be bond price unfriendly? Can you please expand your view?

I think you misread the conclusion. The balance of risks in 2025 is upward pressure on rates, which is bond price unfriendly.

Thanks

The resurgence of inflation, if one month of data can be called that, is known to all focused on it including the Fed. Factors outlined above do not help. In that case why would Fed cut rates in September?

Average men’s economy is flat-lining. Transport sector is showing a lot of weakness. Some anecdotes are piling up. J Lopez has cancelled all of N American tours of this year. Black Keys just did the same. So I am watching T Swift for the end of econ growth of this cycle. Equity market has already signaled this trend. The performance of companies and reaction to earnings report has had a very large dispersion this earning season. End of the first two easy years of this cyclical bull is approaching and market is already getting into stock picking mode. More and more stocks are underperforming their benchmark indices. If those big techs don’t continue to perform it is difficult to see how indices can move up meaningfully. So we are awaiting the second wind, like when we are playing sports.

Surprisingly (or not, if you dig deeper) two stocks which greatly benefit from AI adoption are WMT and COST. But people don’t talk about non-sexy staples. Another sector people don’t talk about is aviation industrials and materials. They are on very strong secular trend with wide moat. Another sector on perpetual up trend is waste treatment/disposal and water supply. No gov/municipality dares to challenge these companies in the contract negotiation. If you ever lived in NYC during strikes by these companies you will appreciate the normal days. Not surprisingly the strikes always happened in summer months when NYC is in unbearable swelter. The wide moat these companies possess is almost insurmountable. Just the regulatory requirement and permit process and environmental evaluation is enough to discourage potential new entrants.

The problem I have with productivity is that it is a calculation which ignores people.

Example….AI is so great that 1 person does everything for the US economy using connected robots and AI avatars. Productivity goes to the moon, but nobody has a job, so who buys anything? What happens to the economy?

Productivity is great if you are an export based country, make more for less , I’m not so sure about a service based economy.

AI will displace more workers. How this does not create more people on gov’t support and fiscal deficits I don’t see.