As the market reacts the weekend attack on Saudi oil facilities, the level of anxiety is mounting. Forbes published an article on Sunday entitled “Attacks on Saudi Arabia are a recipe for $100 oil”.

Bloomberg that this represents the biggest disruption to global oil supply since the Iraqi 1990 invasion of Kuwait.

As visions of the 1974 Arab Oil Embargo and the ensuing recession dance in traders’ heads, this is a timely reminder that the FOMC is meeting this week. Should the supply curtailment become prolonged, how should policy makers react to supply shocks? As well, there is a case to be made that the world is facing more than just one supply shock.

Supply shocks explained

What is a supply shock? Nouriel Robini explained it this way in a Project Syndicate essay:

Over time, negative supply shocks tend also to become temporary negative demand shocks that reduce both growth and inflation, by depressing consumption and capital expenditures. Indeed, under current conditions, US and global corporate capital spending is severely depressed, owing to uncertainties about the likelihood, severity, and persistence of the three potential shocks.

When he wrote the essay, Roubini was referring to the supply shock from the Sino-American trade and currency war, the emerging cold war between the two countries, and a possible third shock involving oil supplies. All three shocks have manifested themselves, and there is little policy makers can do.

In fact, with firms in the US, Europe, China, and other parts of Asia having reined in capital expenditures, the global tech, manufacturing, and industrial sector is already in a recession. The only reason why that hasn’t yet translated into a global slump is that private consumption has remained strong. Should the price of imported goods rise further as a result of any of these negative supply shocks, real (inflation-adjusted) disposable household income growth would take a hit, as would consumer confidence, likely tipping the global economy into a recession.

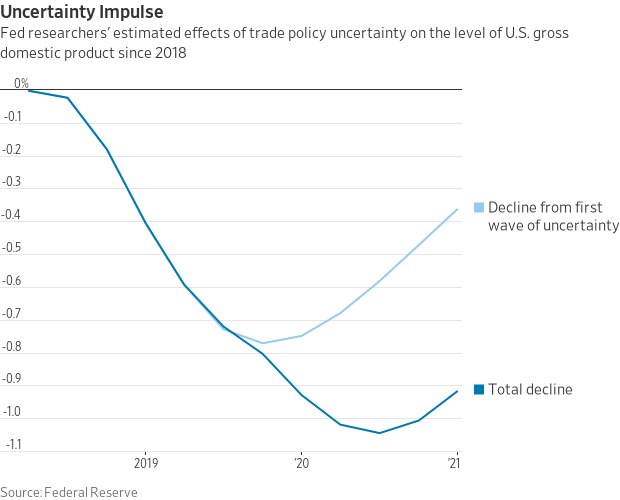

Consider the supply shock stemming from the trade war. A recent Fed study concluded that trade policy uncertainty was on course to reduce GDP growth by about 1%.

The latest NFIB small business confidence survey is revealing, as small businesses have little bargaining power and their views are sensitive barometers of the economy. Trade uncertainty erodes business confidence, and capital expenditures plans get delayed. As the NFIB survey shows, capex plans are rolling over.

Despite Trump`s desire for lower interest rates, there is little the Fed can do to boost the economy even if it were to lower rates. Credit conditions are already very easy. But if confidence about business conditions are low, lowering the cost of credit will have minimal effect on growth.

I would add that trade war uncertainty is not just limited to friction between the US and China. Politico reported that Trump is likely to open up another front in the trade war. This time it will be against the European Union.

The United States has gotten the green light to impose billions of euros in punitive tariffs on EU products in retaliation for illegal subsidies granted to European aerospace giant Airbus.

Four EU officials told POLITICO that the World Trade Organization ruled in favor of the U.S. in the long-running transatlantic dispute and sent its confidential decision to Brussels and Washington on Friday.

The decision means that U.S. President Donald Trump will almost certainly soon announce tariffs on European products ranging from cheeses to Airbus planes. One official said Trump had won the right to collect a total of between €5 billion and €8 billion. Another said the maximum sum was close to $10 billion.

Roubini suggested that the proper short-term policy response to these supply shocks is both monetary and fiscal easing (good luck with passing fiscal stimulus ahead of the election):

Given the potential for a negative aggregate demand shock in the short run, central banks are right to ease policy rates. But fiscal policymakers should also be preparing a similar short-term response. A sharp decline in growth and aggregate demand would call for countercyclical fiscal easing to prevent the recession from becoming too severe.

However, there is little policy makers can actually do over the medium term, as the economy is facing a demand shock (capex drying up from trade war uncertainty, an oil spike is a de facto tax increase). The economy just needs time to adjust to these shocks. An inappropriate policy response will only lead to stagflation.

In the medium term, though, the optimal response would not be to accommodate the negative supply shocks, but rather to adjust to them without further easing. After all, the negative supply shocks from a trade and technology war would be more or less permanent, as would the reduction in potential growth. The same applies to Brexit: leaving the European Union will saddle the United Kingdom with a permanent negative supply shock, and thus permanently lower potential growth.

Such shocks cannot be reversed through monetary or fiscal policy making. Although they can be managed in the short term, attempts to accommodate them permanently would eventually lead to both inflation and inflation expectations rising well above central banks’ targets. In the 1970s, central banks accommodated two major oil shocks. The result was persistently rising inflation and inflation expectations, unsustainable fiscal deficits, and public-debt accumulation.

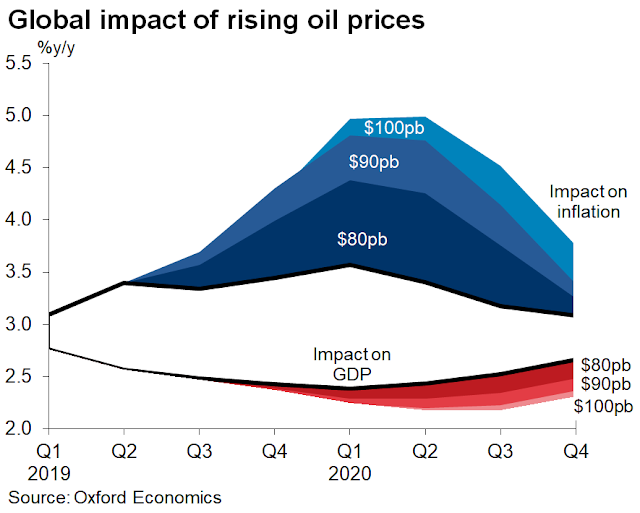

Oxford Economics put some numbers on what could be a dire scenario. The firm modeled what a sustained oil spike would do to growth and inflation in dire case scenarios. Even at $80 oil, inflation would rise to levels that would restrain the Fed from easing, regardless of how much pressure Trump puts on Powell.

Add in the uncertainty restraining business investments, and you have the makings of stagflation induced slowdown.

The oil shock

As I write these words, it is difficult to assess the impact of the oil shock. We have seen short-term oil spikes before, and prices can normalize as the underlying supply situation gets resolved. There are two major questions to consider. How long will it take for flow rates to come back online?

The second and more difficult question is what steps Saudi Arabia can take to prevent a repeat of similar incidents. The energy analyst John Kemp explained it this way in a series of tweets:

ABQAIQ has long been identified as the #1 security risk in the oil market given its centrality to the Saudi export system — it is the top target for terrorists, dissidents, foreign special forces and in the event of armed conflict with Iran.

ABQAIQ’s vulnerability means it is one of the most heavily guarded places on Earth and it has long been thought that it was safe in most circumstances short of war with Iran

SAUDI ARABIA has armed guards to protect the perimeter. The kingdom’s security services target internal threats. The CIA has a large station in the kingdom. And U.S. service personnel are present in significant numbers in the Eastern Province.

ABQAIQ was assessed to be relatively secure from most threats short of open armed conflict with Iran. The recent attack (whether by drone or missile) has falsified that assessment

ABQAIQ attack will force major re-evaluation not only of risks in the oil market (where it has highlighted vulnerability to single point of failure) but also the kingdom’s security strategy (including Yemen conflict and relations with Iran, the United States and regional powers)

SAUDI strategy has been to reinforce alliance with USA; support maximum sanctions on Iran; forward posture in Yemen, Syria and to lesser extent Iraq; while oil system and homeland remain secure. Abqaiq attack raises question whether conflict can be kept outside kingdom’s borders

ABQAIQ attack has hit the most central and critical node for the oil market and at the very core of the kingdom’s political security

ABQAIQ has always been a much greater source of risk for the oil market than Strait of Hormuz. But until the last 48 hours it was assumed to be a high consequence low probability danger so was largely discounted. That won’t be possible any more

For those familiar with electricity and other critical systems that employ N-1 planning to deal with contingencies, Abqaiq was the N in the world oil market

Short-term question is how to repair Abqaiq and how to protect it from further attacks. Long-term question is how to reduce reliance on the site by increasing redundancy and re-routing oil flows

Even if the infrastructure damage were to be repaired quickly, expect a supply security risk premium to be embedded in oil prices for the foreseeable future.

In addition, this is President Trump`s first real foreign policy test based on a situation that was not based on his initiative. He recently dismissed John Bolton, a known Iran hawk, as National Security Adviser. How he handles this challenges could be crucial to his re-election chances, not to mention a possible source of geopolitical instability. Will the market have to price in a Trump uncertainty premium, as well as a security risk premium to oil prices?

These conditions can’t be positive for stock prices when the market closed last week at an elevated forward P/E of 17.0.

In the meantime, get some popcorn, sit back, and enjoy the show.

I talked with people from one of the major engry companies today and their take on the damage the drones did ( they’ll be back in operation in a few weeks. Just above-ground damage).

That seems to be the consensus.

Cam: Are you expanding your S & P 500 short?

No, I did not want to chase the market down.

With the Japan vs South Korea trade “conflict” still going on, we soon might have to add semiconductors and related materials to the list. Semiconductors have become key components for so many products and the supply chains are very vulnerable. For instance, it took SK Hynix several months to fully restore output capabilities when a fire hit one of their production lines in September 2013. Semiconductor production lines usually ramp up in August/September for production of the new iPhones.

This is a very alarming post Cam. Any supply side oil shocks would be disastrous going into a weak global economy. A trade spat with EU would add fuel to fire and perhaps a call to go to minimum level of stock market exposure for portfolios with less than a decade of time to culmination (retirement).