Bloomberg reported that Carmen Reinhart had a chilling warning about Hong Kong:

Hong Kong’s rolling political turmoil could prove a tipping point for the world economy, Harvard University economist Carmen Reinhart said.

Noting an incidence of shocks that have rattled global growth, including the intensifying U.S.-China trade war, Reinhart cited Hong Kong as among her main concerns. Having previously warned that Hong Kong faces a housing bubble, she said the world economy could be hit by “shocks with a bang or with a whisper.”

“One shock that is concerning me a great deal at the moment is the turmoil in Hong Kong,” which could impact growth in China and Asia generally, Reinhart said in an interview with Bloomberg Television’s Kathleen Hays.

“These are not segmented regional effects, these have really global consequences. So what could be a tipping point that could trigger a very significant global slowdown, or even recession — that would be a candidate, that could be a candidate,” said Reinhart, who specializes in international finance.

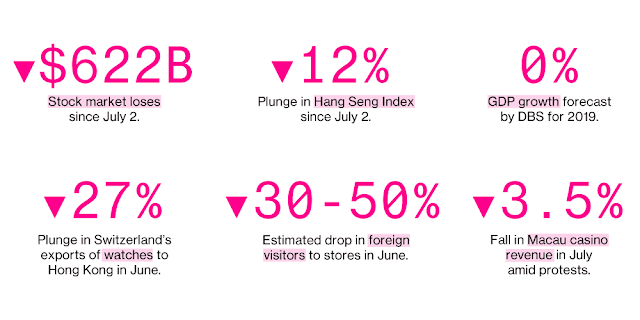

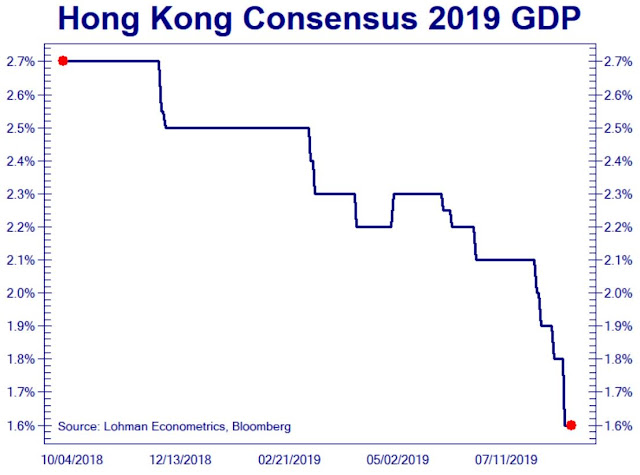

Indeed, the unrest has taken a toll on the local economy.

…and GDP growth expectations are tanking.

Let me calm everyone down, and you can timestamp this forecast. China will not send troops into Hong Kong in 2019, which reduces tail-risk. At the same time, however, investors should not ignore Carmen Reinhart’s warnings either.

Hong Kong’s protests in context

Did you ever have a fight with Significant Other, when the fight about X, but the real hidden issue was Y? Here are what some of the underlying issues behind the Hong Kong protests.

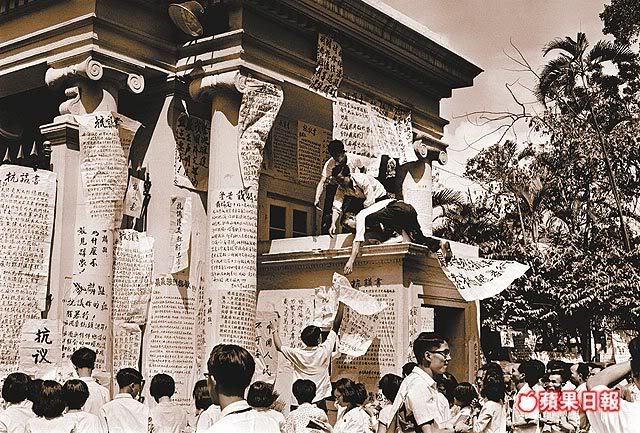

I left Hong Kong as a child in 1967 for Canada, when the colony was gripped by riots and bombings. The protests was sparked by a 5c increase in the fare on the Star Ferry, which was at the time the only way of getting to the island of Hong Kong from Kowloon. It eventually escalated into bombings and riots.

While the apparent problem was economic discontent, which was very real, the hidden issue was the creeping influence of Mainland China’s influence into the British colony. Not only was the Cultural Revolution at its height, local opposition to the Vietnam War did not help matters. They were daily demonstrations at the gates of the Governor’s Mansion, with protesters shouting with Mao’s Little Red Book, which I can recall by watching from a nearby hill. My parents were abroad at the time, and they were horrified when they learned of my proximity to the protests.

That was then, this is now.

When viewed from a distance, the apparent cause of the discontent is China’s heavy-handed approach of imposing an extradition bill on Hong Kong. Many of us in the West view the conflict as a protest against the imposition of China’s will on Hongkongers. While those issues are very real, there is a deeper underlying cause of the discontent.

The problem is inequality, as outlined by the New York Times. While I have met many bankers who hold HK up as an example of pure capitalism, it is also the land of yawning inequality, where the American Dream of getting ahead is all but dead.

Rents higher than New York, London or San Francisco for apartments half the size. Nearly one in five people living in poverty. A minimum wage of $4.82 an hour.

Hong Kong, a semiautonomous Chinese city of 7.4 million people shaken this summer by huge protests, may be the world’s most unequal place to live. Anger over the growing power of mainland China in everyday life has fueled the protests, as has the desire of residents to choose their own leaders. But beneath that political anger lurks an undercurrent of deep anxiety over their own economic fortunes — and fears that it will only get worse.

“We thought maybe if you get a better education, you can have a better income,” said Kenneth Leung, a 55-year-old college-educated protester. “But in Hong Kong, over the last two decades, people may be able to get a college education, but they are not making more money.”

An article in The Economist picked up on this theme of inequality and property unaffordability.

Thanks to light regulation, independent courts and a torrent of money from China, Hong Kong has long been a global financial centre. But many of the resulting jobs are filled by outsiders on high salaries, who help push up property prices. Mainlanders seeking boltholes do too. And then there is the contorted market for housing. The government artificially limits the supply of land for development, auctioning off just a little bit each year. Most of it is bought by wealthy developers, who by now are sitting on land banks of their own. They have little incentive to flood the market with new homes, let alone build lots of affordable housing. The average Hong Kong salary is less than HK$17,000 ($2,170) a month, hardly more than the average rent. The median annual salary buys just 12 square feet, an eighth as much as in New York or Tokyo.

The discontent found its focus on China’s role in Hong Kong (from the NYT):

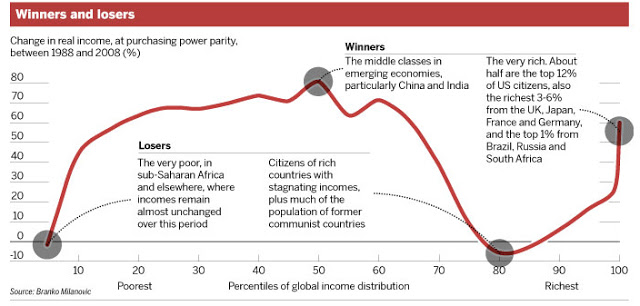

These issues were at the fore five years ago, when protests known variously as Occupy Central or the Umbrella Movement shut down parts of the city for weeks. Similar protests, such as the Yellow Vest movement in France, echo worries that a booming global economy has left behind too many people.

Today, protesters are focusing on the extradition bill, which Hong Kong leaders have shelved but not killed, and a push for direct elections in a political system influenced by Beijing. Hong Kong, a former British colony, operates under its own laws, but the protesters say the Chinese government is undermining that independence and that the leaders it chooses for Hong Kong work for Beijing, for property developers and for big companies instead of for the people.

While I am not discounting the seriousness of the political issues, this is just another manifestation of populism that has appeared all around the world. We can see that in the politics of Marine Le Pen in France, Matteo Salvini in Italy, and Trump’s MAGA beliefs in the US. In the West, the discontent is attributable to Branko Milanovic’s finding that the era of globalization left the developed world’s middle class behind, while enhancing the income gains of emerging market economies, and the global rich elite who engineered the globalization boom. This has manifested itself in anti-immigrant views in many developed countries.

China’s likely response

While the big picture is always enlightening, and interesting, what does that mean in the real world? What will China do, and what does that mean for the risks that Carmen Reinhart raised?

There are two reasons why China is unlikely to militarily crackdown in Hong Kong in the short run. The first reason is Taiwan’s election, which will occur in January. Beijing will not intervene if it wants to keep any hopes alive of eventually coming to a One Country-Two Systems style Hong Kong solution with Taiwan. Any appearance of PLA units in Hong Kong will harden the position of the Taiwanese electorate, aid the rise of the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party, and scuttle any prospect of discussion of reunification in the near future.

Beijing also faces some practical problems of a Tiananmen Solution in Hong Kong, as Minxin Pei pointed out in a Project Syndicate essay:

After the Tiananmen crackdown, the Communist Party of China’s ability to reinstitute control rested not only on the presence of tens of thousands of PLA troops, but also on the mobilization of the Party’s members. In Hong Kong, where the CPC has only a limited organizational presence (officially, it claims to have none at all), this would be impossible. And because the vast majority of Hong Kong’s residents are employed by private businesses, China cannot control them as easily as mainlanders who depend on the state for their livelihoods.

The economic consequences of such an approach would be dire. Some CPC leaders may think that Hong Kong, which now accounts for only 3% of Chinese GDP, is economically expendable. But the city’s world-class legal and logistical services and sophisticated financial markets, which channel foreign capital into China, mean that its value vastly exceeds its output.

In other words, the risk/reward ratio of intervention is highly unfavorable. At a minimum, don’t expect any action until the January 2020 Taiwanese election.

A contrarian buy?

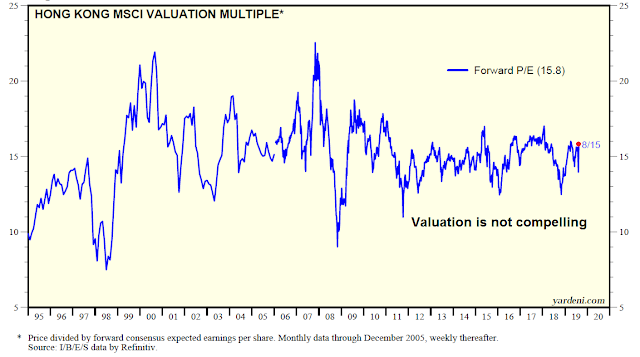

If the tail-risk of Chinese intervention is largely off the table, does that mean you should be buying Hong Kong equities? Despite the decline in the HK market, valuation is hardly compelling. With the region’s economy tied to China, whose growth is experiencing some deceleration, the prudent course of action is to wait.

There is the additional risk of further escalation in the trade war. Trump is running out of Chinese imports to tariff. If he chooses to escalate tensions, the next front may be geopolitical, such as support for Taiwan, which is already evident from the latest arms sales, or overt support for Hong Kong’s protest movement.

Carmen Reinhart’s evaluation of Hong Kong as a possible tipping point is correct. The risks are still there. It is better to wait before buying.

Trump recently approved selling 66 F-16V to Taiwan – the most important arm deal ever since the first Bush sold earlier verion F-16 in 1992. Normally I would expect very aggressive reaction from China side, and lots of media coverage and angry among nationlist people. This time it’s been very quiet – just a sign of how much distraction the HK issue has.

China has tried to push back on the US tariff on many occasions and each time was met with tough response from President Trump. I believe China does not want another conflict with President Trump knowing this battle is already lost.

Cam, thanks for the personal perspective about historical HK. I travelled there in 1997 to witness the handover; it was a time of nervous optimism. I wonder how history would have been different if the British had actually seeded the island with universal suffrage during their rule. I think the west often conveniently overlooks that detail when criticizing the people’s current condition.