Is the Fed about to blink? There has been a growing chorus of analysts like Kevin Muir at The Macro Tourist who thinks so.

It is clear to me the Federal Reserve was intent on raising rates until something broke, and that last week enough things “broke” that they finally blinked.

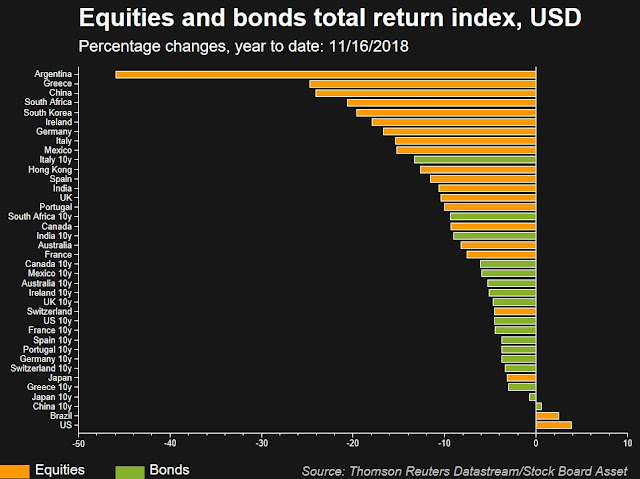

What broke? Muir mentioned a number of possible triggers. First, there is the dire picture of global asset returns this year.

He also cited:

- The collapse in oil prices;

- Widening credit spreads; and

- Political pressure from the White House (the WSJ reported that Trump expressed displeasure with Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin for his recommendation of Jerome Powell for the position of Fed Chair because the Fed’s tightening policy).

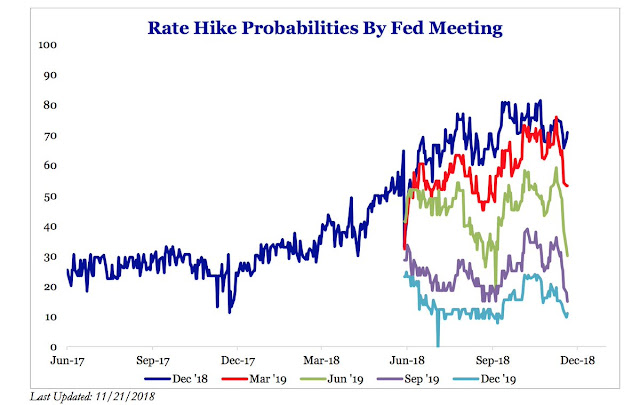

As a result, the trajectory of Fed Funds expectations has collapsed.

Muir concluded that it’s time for investors to prepare for a shift in monetary policy:

The Federal Reserve had previously been plugging their ears and telling the global financial community nah-nah-nah-we-can’t-hear-you-we’re-going-to-keep-raising-come-hell-or-high-water, but the economic and financial market weakness that was previously confined to the rest of the world, has finally come to America. The Federal Reserve is now very close to being on hold for the indefinite future. Sure, they will probably raise once more this December, but it’s most likely a one-and-done. Or at very least, much more a one-and-we-will-see.

What does this mean for the market? Tons. Whereas before investors were hiding in American stocks and shooting every other asset class, it’s probably time to do the opposite. Buy emerging markets. Sell U.S. dollars. Play for a steepener in the American yield curve. Buy commodities.

Now maybe it’s too early. Maybe there is more pain to come before the Fed truly panics. That could be. We will have to watch the Fed carefully for clues.

Does this mean the Powell Put is coming into play?

The alternative view

For the contrary view, I turn to seasoned Fed watch Tim Duy, who wrote a Bloomberg opinion piece that the Fed already has a slowdown embedded into its forecast, and it is unlikely to pause until economic growth underperforms its estimated long-term growth rate of 1.8% [emphasis added].

What’s going on here? The challenge for the Fed is managing an economy that is transitioning through an inflection point. The odds are very high that economic growth slows markedly next year. The lagged impact of the Fed’s seven rate hikes over the last two years (which is already evident in housing), fading fiscal stimulus and slower global growth all point in this direction. That is the Fed’s baseline forecast as well.

But will growth slow enough to ease what the Fed believes are underlying inflationary pressures? In general, central bankers believe the economy currently operates at or beyond full employment. To be sure, they are not sufficiently concerned to boost rates at a faster pace, believing instead they can use the opportunity to squeeze some extra slack from the labor market. Policy makers are, however, sufficiently concerned about the potential for overheating that they would prefer that unemployment didn’t drift much lower.

From the perspective of the Fed, that means growth needs to slow to something closer to 1.8 percent, which happens to be the Fed’s estimate of the longer-run growth rate. As of last month, the Fed forecast 2.5 percent growth for 2019, even with continued rate hikes. In other words, a slowdown to 2.5 percent leaves activity still too robust to ease the Fed’s concerns.

If the 1.8% GDP growth rate is the Fed’s line in the sand, how does that measure up to current forecasts? CNBC reported that Goldman does not expect growth to slow to that level until late 2019:

“Growth is likely to slow significantly next year, from a recent pace of 3.5 percent-plus to roughly our 1.75 percent estimate of potential by end-2019,” wrote Jan Hatzius, chief economist for the investment bank, in a note to clients on Sunday. “We expect tighter financial conditions and a fading fiscal stimulus to be the key drivers of the deceleration.”

The bank sees the economy expanding at 2.5 percent in the fourth quarter of this year, down from 3.5 percent last quarter. Real GDP growth will come in at 2.5 percent again in the first quarter of 2019, but then will slow to 2.2 percent, 1.8 percent and 1.6 percent in the next three quarters, respectively.

A separate CNBC report showed similar expectations from JP Morgan:

The economists expect that growth will hold above 2 percent in the first and second quarter, at 2.2 and 2 percent respectively, before falling to 1.7 percent in the third quarter and 1.5 percent in the fourth quarter. The economy last grew at less than 2 percent in the first quarter of 2017.

The Congressional Budget Office forecast was even more bullish. It expects real GDP growth of 2.4% in 2019 and 1.7% in 2020.

Duy went on to set out the conditions for a Fed pause:

What does the Fed need to see to change course? In the near term, it would require a fairly dramatic change in financial conditions. Falling stocks are not enough, especially considering the concern that equity markets were overvalued earlier this year. The stress on the financial system needs to broaden. I look back to the 2015-2016 period as a reference.

Even then, financial stress was matched with softer economic data, particularly in manufacturing. That’s what would shift the Fed’s perspective. Over the medium term, such as the next six months, the Fed would increasingly shift to a more dovish stance if evidence mounts that the economy is slowing in line with the Fed’s forecasts. The more slowing seen, the more the Fed will see the time for a pause is at hand. Of course, on the other side of the coin, if the slowing is not as deep as feared, then the Fed will track in a more hawkish direction.

That’s what it means to be “data dependent”.

Resolving the dilemma

One of the challenges for investors is the interpretation of Fed intentions. The Powell Fed has backed off the more explicit policy guidance program of the Yellen Fed, and it has now becoming more data dependent. In this environment, Fedspeak is likely to be more confusing than helpful, and investors should focus on the evolution of the dot plot rather than the speeches of Fed officials.

Even though the Phillips Curve has shown itself to be very flat this expansion cycle, the DNA of the Fed still believes in this model, and I am closely watching how employment and wage pressures are developing in the months ahead.

Consider this CNBC report that an astounding 67% of workers earning over $100,000 expect to change jobs in the year ahead:

According to a new report from Ladders, most workers making more than $100,000 are planning to quit their jobs within a year.

Ladders surveyed more than 50,000 workers earning over six-figures and found that 67 percent see themselves at the different company in just six months. About 40 percent would move out-of-state for just $10,000 more in pay.

“The gold rush of 2019 is on,” Ladders CEO Marc Cenedella tells CNBC Make It. “With an incredibly strong employment market, more professionals than ever are on the lookout for a better future.”

This kind of behavior by highly paid workers are screaming wage inflation, which is a development that the Fed cannot and will not ignore.

In addition, a BLS researcher also found that the quits to layoffs and discharges rate seem to lead growth in Non-Farm Payroll (red line). There is also apparent relationship between temporary jobs and NFP (blue line). Both of these indicators are pointing to a healthy jobs market.

Bottom line: The Fed is not going to blink until we start to see some definitive signs of deterioration in the jobs market and wage pressures.

Be careful for what you wish for. In the past when the Fed has paused after a long run up in rate hikes, a market peak and a recession were often around the corner. For example the Fed paused in the year 2000 but markets peaked and two years of bad markets followed.

Peter Brandt, a very respected Technical Analyst, is seeing a strong Hikkake buy signal on NQ.

https://twitter.com/PeterLBrandt/status/1067157419355197440