Preface: Explaining our market timing models

We maintain several market timing models, each with differing time horizons. The “Ultimate Market Timing Model” is a long-term market timing model based on the research outlined in our post, Building the ultimate market timing model. This model tends to generate only a handful of signals each decade.

The Trend Model is an asset allocation model which applies trend following principles based on the inputs of global stock and commodity price. This model has a shorter time horizon and tends to turn over about 4-6 times a year. In essence, it seeks to answer the question, “Is the trend in the global economy expansion (bullish) or contraction (bearish)?”

My inner trader uses the trading component of the Trend Model to look for changes in the direction of the main Trend Model signal. A bullish Trend Model signal that gets less bullish is a trading “sell” signal. Conversely, a bearish Trend Model signal that gets less bearish is a trading “buy” signal. The history of actual out-of-sample (not backtested) signals of the trading model are shown by the arrows in the chart below. The turnover rate of the trading model is high, and it has varied between 150% to 200% per month.

Subscribers receive real-time alerts of model changes, and a hypothetical trading record of the those email alerts are updated weekly here.

The latest signals of each model are as follows:

- Ultimate market timing model: Buy equities

- Trend Model signal: Neutral

- Trading model: Bearish

Update schedule: I generally update model readings on my site on weekends and tweet mid-week observations at @humblestudent. Subscribers receive real-time alerts of trading model changes, and a hypothetical trading record of the those email alerts is shown here.

War is hell

War is hell, even trade wars. The world is again at risk of lurching into a global trade war. Last Friday, Trump announced the imposition of 25% tariffs on $34 billion in Chinese exports, with another proposed list totaling $16 billion that is subject to public comment and review. China has responded with retaliatory tariffs on $34 billion in American exports, mostly in agricultural commodities and automobiles.

Under these circumstances, it is useful to revisit my analysis written in January of the possible fallout under such a scenario (see Could a Trump trade war spark a bear market?). I had highlighted analysis from the Peterson Institute in 2016 modeling the effects of a full blown and abortive trade war on the US economy. The economy would lapse into a mild recession in the former case, but sidestep a recession in the latter case. However, the results did appear anomalous as I pointed that that the observation of (then) New York Fed President Bill Dudley that the economy fell into recession whenever unemployment rose 0.3% to 0.4%, as it would in the modeled result of the abortive trade war.

President Donald Trump tweeted in the past that “trade wars are good, and easy to win”. What if he is right, and trade partners either backed down from retaliatory tariffs, or only imposed limited tariffs?

How would “winning” a trade war look like? Let’s put on our rose colored glasses and take a look.

Vulnerable trade partners

Trump’s trade policy has two main objectives. The long term objective is to bring manufacturing jobs back into the United States, and a shorter term goal is to shrink the trade deficit.

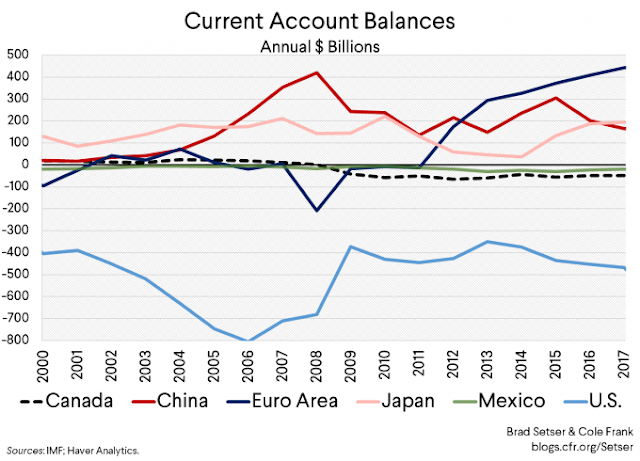

For some perspective, Brad Setser at the Council on Foreign Relations depicted the US current balance in two important ways. The first is in absolute dollar terms.

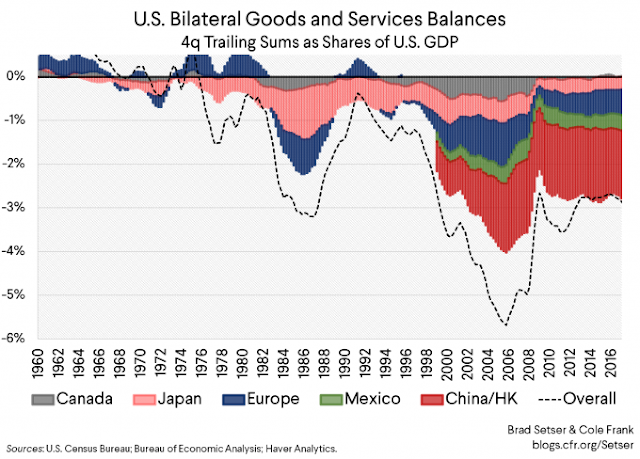

The second is as a percentage of US GDP.

Setser went on to observe that China and Germany have the lion’s share of the global manufacturing trade surplus:

China’s annual manufacturing surplus is still around $900 billion (for comparison, Germany’s manufacturing surplus is around $350-400 billion depending on the exchange rate and the U.S. deficit in manufacturing is around $1 trillion) and doesn’t show any sign of falling. I don’t see signs that the (modest) real appreciation this year will seriously erode China’s competitiveness—though it should moderate China’s export outperformance (Chinese goods export volumes grew at a faster pace than global trade in 2017).

The accompanying chart from Our World in Data shows trade flows as a share of GDP. The American economy is less sensitive to trade flows than either China or Europe, though the trade sensitive of European countries is exaggerated in the chart as much of the trade represent flows within the EU. Nevertheless, exports make up about 20% of China`s GDP, and Germany is the locomotive of export growth in Europe. These circumstances make them especially vulnerable to trade sanctions.

Fragile China

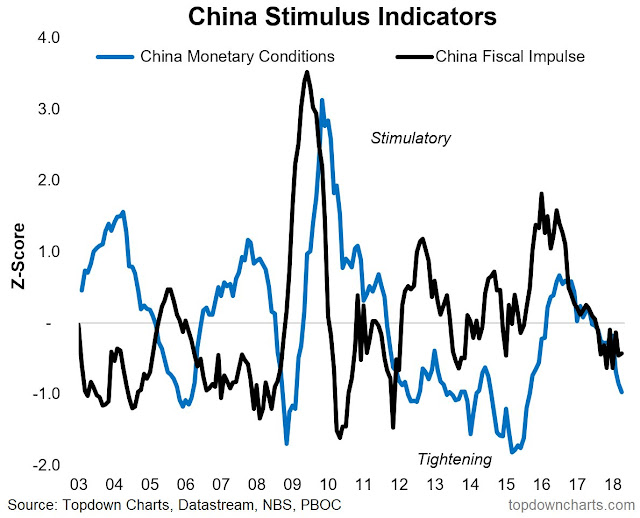

Moreover, China’s financial conditions are coming under increasing stress. A trade-induced slowdown is the last thing the economy needs. Last week, I had highlighted analysis from Callum Thomas that both fiscal and monetary policy were tightening.

The New York Times reported that China’s credit crackdown raising the risk of tanking its economy:

Beijing has been concerned in recent years about the increased reliance on credit to keep the economy expanding briskly, worrying that it could lead to a financial crisis, or to a long period of stagnation like the one in Japan after the real estate market burst in the early 1990s.

But curbing debt may have significant consequences in China and elsewhere. Countries around the world are much more closely tied to China than ever before, because of its role not just as the world’s biggest manufacturer by far but also, increasingly, as a consumer. An economic slowdown in China — coupled with the knock-on effects of widening trade disputes and slowing growth in Europe — may augur poorly for a global economy that even recently seemed in rude health.

Domestically, China’s credit crackdown has affected smaller businesses hardest. Though the country often appears to be dominated by its vast conglomerates and hulking state-owned enterprises, its economy is, in reality, somewhat more reliant on small businesses than its Western counterparts. And the way Beijing has gone about curbing lending in recent months is unintentionally hitting the most entrepreneurial segments of the economy, the governor of China’s central bank acknowledged in a speech on Thursday in Shanghai.

Beijing is facing the conundrum of trying slow credit growth while sustaining economic growth. They do not the additional headache of a trade war to exacerbate the effects of any slowdown.

Fragile Europe

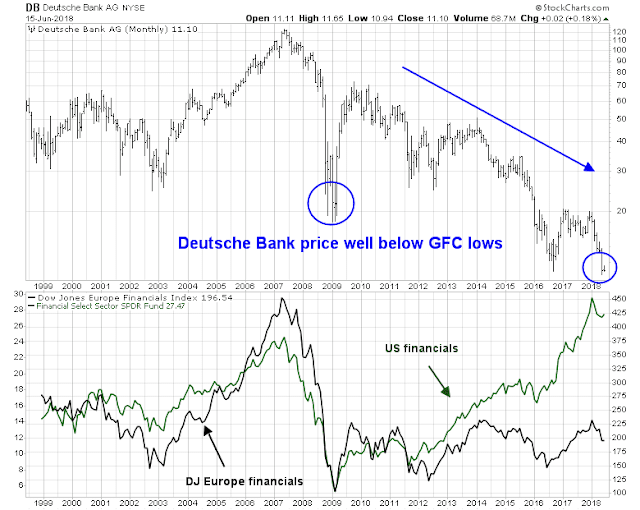

Europe, on the other hand, faces a different kind of fragility. In addition, to the well known problems of trade openness, the European banking system never solved the excess leverage problems from the last cycle. As a result, ever small wobbles in the EU economy will have an outsized effect on financial stability. The poster boy for Europe`s banking problems is Deutsche Bank, whose share prices is now trading at levels below the lows set during the Great Financial Crisis. Moreover, European financial stocks have dramatically underperformed US financials during the same period.

What if trade partners like China and the EU decided to “eat the loss” and either refrained from trade retaliation, or responded with light, but highly targeted retaliation? That’s because global tariff rates are already very low, especially in the developed economies. Trump’s imposition of a tariff amounts to an import tax that hurts Americans as much as the exporting producer.

An asymmetric trade war?

Why not do nothing and either refrain from retaliation or retaliate in a highly surgical fashion? Let’s consider such a scenario of the short run effects on the exporting country.

Begin with China. Chinese economic growth is highly dependent on trade, and tariffs would bring economic growth to a screeching halt. A Chinese growth slowdown would crater the economic growth of most of Asia, and commodity suppliers like Australia, Canada, and Brazil.

Europe would not fare any better. German exports would tank, and Germany has been the engine of growth in the eurozone. The European banking system would wobble, and financial risk would spike. At a minimum, we would see a magnified repeat of the Greek Crisis of 2011.

How would the markets react? Risk-off would be the order of the day, but with the US economy partly insulated from these offshore troubles, Treasury assets would become the safe haven of choice. The USD would soar, which makes US exports less competitive.

So much winning.

How would the Fed react? Fed watcher Tim Duy gamed the Fed’s reaction from a possible trade war. In a limited trade war, the Fed would do nothing:

Currently, the Fed looks on course for three –and maybe four — rate hikes in 2018 of 25 basis points each. With economic growth sufficient to put downward pressure on an already low unemployment rate, central bankers will seek to push policy rates to a neutral level. Otherwise, the Fed believes the economy faces a risk of overheating.

Escalating trade battles potentially impact this forecast by causing demand to contract and supply shocks. An example of negative demand shocks are retaliatory tariffs on U.S. manufactured goods and farm products. If America’s trading partners focus primarily on tariffs that narrowly target firms in Republican leaning states, such as levies on Tennessee whiskey, Harley-Davidson motorcycles and cheese, the overall impact on economic activity will be fairly minimal.

Narrowly targeted retaliation by our trading partners will thus induce more political and local pain than aggregate weakness. And note that some of the overall damage on manufacturing will be mitigated by the rebound in oil prices and associated increase in drilling activity. If the overall economic impact of such retaliation is minimal, so too will be the Fed’s response. To be sure, if the negative demand shock is stronger than I expect, the Fed will see diminishing risk of overheating and change policy in a more dovish direction.

Another possibility is the Fed continues on its tightening path by looking through the inflationary implications of higher tariffs:

More interesting than demand shocks, which have straight forward implications for policy, is the possibility that the Trump administration’s approach yields an escalating supply shock that restricts the productive capacity of the U.S. Such shocks both constrain economic activity and raise prices. The U.S.-imposed tariffs on steel are a perfect example. Indeed, the possibility of a broad-based disruption from such tariffs is exactly why a nation should be wary of targeting intermediate goods in a trade war.

It is tempting to conclude that the Fed will react to a negative supply shock via tighter policy, especially when central bankers already face the prospect of an overheated economy. This, however, will not be the case as long as the Fed believes inflation expectations remain well-anchored. Rather than shift to a more hawkish stance, the Fed will look through any spike in prices as temporary and instead focus on the negative impacts on economic activity. If they conclude that those negative impacts will continue even after the price shock fades, central bankers might even shift to a more dovish stance.

The final outcome to consider is the Arthur Burns Fed solution of an accommodative Fed, which sets off an inflationary spiral:

The Fed would be driven in the opposite direction if the economy faced a series of negative supply shocks, global trade conflicts escalate and those shocks trigger a change in consumer behavior such that inflation expectations become tilted to the upside. That kind of shift occurred in the late 1960’s, leading to the Great Inflation period. With that episode still looming large in the Fed’s psyche, policy makers would respond with a more hawkish policy stance.

The last case represents a worst-case scenario for financial markets, in that it’s a toxic combination of faster inflation, weaker growth and tighter monetary policy. It would also put the Fed in the Trump administration’s crosshairs. I very much doubt President Donald Trump would sit quietly and respect the Fed’s independence if economic growth faltered. To be clear, this is not my baseline scenario. My baseline is that the scope of the trade impacts in aggregate are too limited to change the direction of policy. But market participants should remain wary of risks to this baseline.

Duy’s analysis suggests that the Fed would continue to tighten in the face of slowing economic growth from abroad. The US economy would then suffer the double whammy of hawkish Fed policy that tightens the economy into a slowdown, and declining demand from abroad.

A recession would ensue. USD assets would rise as Treasuries become the ultimate safe haven, which makes US exports even less competitive. The good news is the trade deficit tends to fall in a recession. So much winning, how can anyone stand it?

It all started when he hit me back!

The above analysis is dependent on the no or limited retaliation from trade partners. What could happen if the worse happened and the war disintegrated into tit-for-tat rounds of rising tariffs? The Washington Post reported that former Trump advisor Gary Cohn stated that a trade war could undo the benefits of the last tax bill [emphasis added]:

Gary Cohn, who served as Trump’s director of the National Economic Council but left amid a rift over the president’s trade policies, said that retaliatory tariffs between countries could drive up inflation and prompt American consumers to take on more debt, possibly pushing the country into another economic downturn.

“If you end up with a tariff battle, you will end up with price inflation, and you could end up with consumer debt,” Cohn, a former Goldman Sachs executive, said at a Washington Post event. “Those are all historic ingredients for an economic slowdown.”

Asked if the trade battle could erase the gains to the American economy from the tax law, Cohn said: “Yes, it could.”

Megan Greene of Manulife Asset Management wrote in the FT that, in the case of a limited trade skirmish, the benign outcomes from macro-economic forecasts don’t tell the entire story.

However, the models largely ignore that the effects of a trade war would hit some industries and regions harder than others. This will become even more of an issue if President Trump follows through on threats to impose 25 per cent tariffs on imported automobiles. The Canadian, Mexican and German auto industries would suffer significantly, even if the overall impact is muted.

These benign predictions are probably flawed in other ways. First, most models are not granular enough to reflect the disruption in global supply chains that would result from tariffs. These are likely to provide the biggest drag on growth from the tension over trade. Some car parts cross the Mexican, Canadian and US borders several times before they end up in a finished vehicle. If Nafta collapses, would carmakers raise prices, absorb additional tariffs or find ways to procure all of their parts in one country?

Second, it is difficult to model the impact of trade-related uncertainty on business sentiment. The stalled Nafta negotiations are starting to affect Canada through lost or deferred business investment.The trade wars could quickly extend into areas that are even harder to quantify. When the US first threatened an additional $100bn in tariffs on Chinese imports, it became clear that China could not respond in kind; it simply does not import enough US goods. But it could hit back by creating more bureaucratic hurdles for US companies operating in China, and interfering with licensing. The impact of such steps would be hard to measure in economic forecasts.

The political blowback is likely to be fierce for Trump. Even in the case of a trade dispute with Canada, CNBC reported that states that supported Trump would get hit the hardest in a Canada trade war.

Further, a report surfaced that Canada floated the idea of sanctioning Trump’s businesses rather than retaliating with more tariffs:

Canadian Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland said Tuesday that she is open to using a law normally reserved for leaders responsible for human rights violations to impose retaliatory sanctions on the Trump Administration. Those sanctions would target the administration itself rather than the American people.

The Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act, also known as the Magnitsky law, would allow Ottowa (to impose travel bans and asset freezes on foreign leaders. Regina-Lewvan MP Erin Weir proposed the measure during a Question Period with Freeland earlier this week. Weir noted that the law might be particularly useful because Trump has “made himself vulnerable” by maintaining personal business interests.

The Europeans have been the masters of politically targeted trade retaliation. The Chinese have also learned, by imposing tariffs on American farm exports, whose producing states mainly voted for Trump in the last election.

In short, war is hell. Even if you win, a one-sided trade war is likely to induce a global recession.. A full-blown trade war is likely to cause even greater damage.

The week ahead

If the market had been really spooked about trade policy, stock prices would have been off 1-2%. Instead, the SPX fell only -0.1% on Friday after the White House announced the latest round of tariffs on Chinese exports, though it was off -0.4% for most of the day, and quadruple witching positioning may have accounted for a late day rally.

For now, market internals show relative nonchalance over trade war risks. Domestic large cap companies, which should be relatively insulated from trade tensions, are underperforming the overall index.

In the absence of political and trade policy fears, the fundamentals are strong. Last week’s report of retail sales was unusually strong. In general, the Citigroup Economic Surprise Index seems to have survived the seasonal weakness often seen in H1 and appears to be turning around.

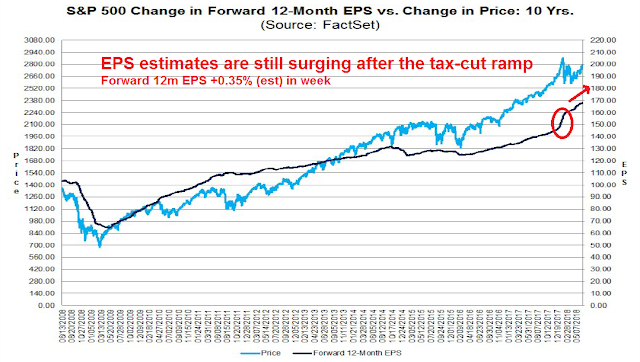

The latest update from FactSet shows that EPS estimate revisions continue to strengthen after the tax bill related surge earlier in the year. Moreover, Q2 earnings guidance is better than average, which points to continuing fundamental momentum that is supportive of higher stock prices.

I wrote last week that the market needed a brief period of correction or consolidation. Since March, the SPX had exhibited a pattern of breakdowns out of a series of rising wedges, and the tops of these formations were coincidentally marked by either a breach or touch of the lower Bollinger Band by the VIX Index. That pattern continues to hold. If history is any guide, these corrective periods tend to last about two weeks, which puts the end of the correction about the end of next week. Bulls can be encouraged by the pattern of progressively shallow corrections, which is an indication of intermediate term strength. Support can be found at about the 2740 level, which represents downside risk of only about 1%.

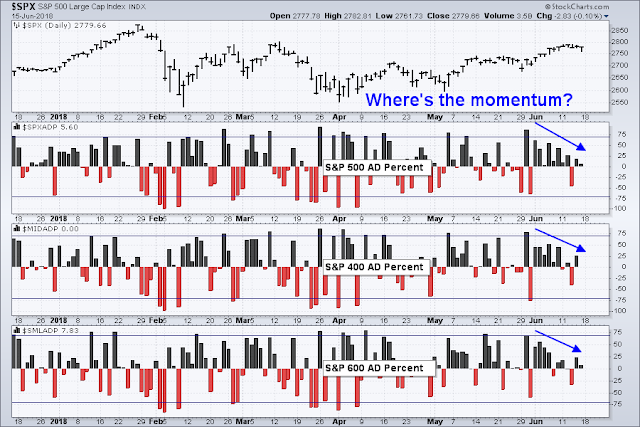

In the meantime, short term breadth metrics are weakening across the market cap spectrum. Until the market can start to show some strength and momentum, the correction or consolidation isn’t over yet.

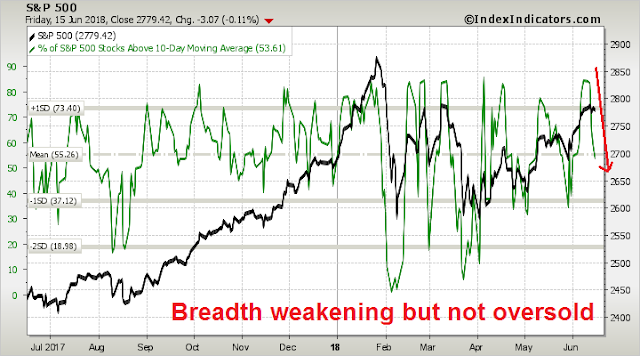

As well, medium term (3-5 day) breadth indicators from Index Indicators are showing negative momentum, but readings are neutral and not oversold. These conditions are suggestive of further downside potential over the next week.

My inner investor remains bullish, and he is not worried about 1% squiggles in the stock market. My inner trader put on a modest short position in anticipation of mild weakness next week.

Disclosure: Long SPXU

Excellent analysis this week.

Excellent. Clear and well articulated.

R. Crusoe, stranded on a desert island, found that he could fashion a board for his house from a tree every 16 days. One day an identical board washed up on his beach. His man suggested he throw this imported board back in the ocean immediately, lest he cost himself 16 days work.

Cost of timber and steel in the US is already up, as reported by the American users of these two commodities. Yes, America will reduce its trade deficit with China. However, substituting Chinese manufactured goods with US goods will cost US consumer in the form higher prices. China may reduce its import of corn and Soybean from US farmers, hurting American farmers. Canadian and South American farmers may be beneficiaries.

Reduced trade deficit with China will make good on president’s campaign promise. Let us see if German cars will be next on the tariff list. In the end, trade wars will be painful, as history shows.